フィリップ・マガリャインシュ: 私たちファラの活動は、辺獄にあるのです - つまりクライアントの無関心と私たちサイドの過剰な野心や熱意との狭間 - ということですが。それは長谷川逸子が70年代に初めて住宅を設計した時の状況と非常に良く似ているでしょう。

あなたの最近出版された日本の住宅に関する本には、柿生の住宅の図面と写真が載っていますよね。そこで分析された住宅の中から、柿生の住宅を今回選ばれた理由は何なのでしょうか?

この住宅は、非常に経済的に作られています。ありきたりな要望による平凡な建設物。中心地から離れた郊外の安価な住宅。ところが、至極平凡とも言えるような外観とフェノメナルな内部構成との不一致 - テクトニックな意味ではなく、空間的そして象徴的な意味でのですが - は驚きですね。イツコは、この住宅の内部に隠された秘宝を守るために、外からの存在感をわざと消すように設計しているように思えるのです。

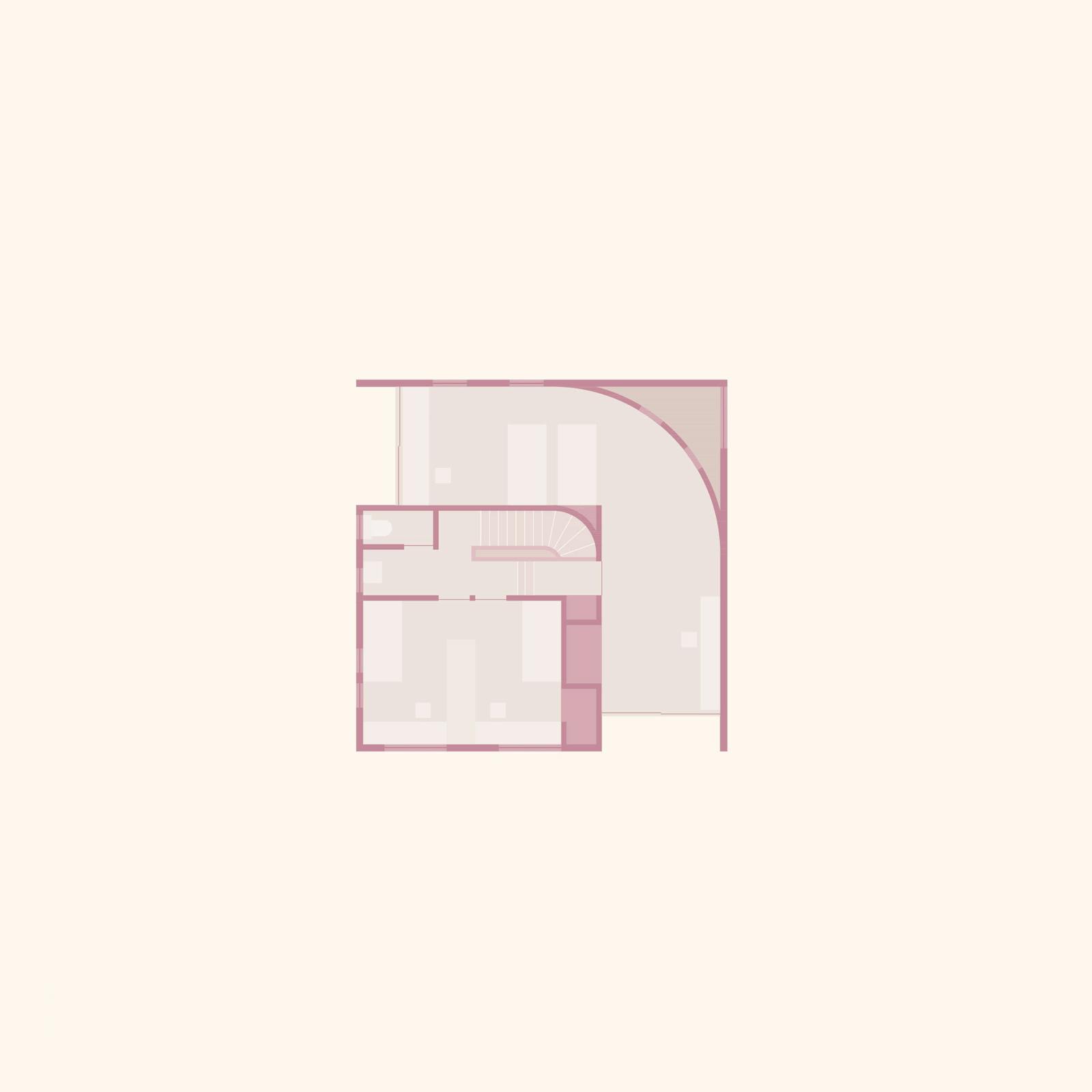

この住宅には二つと半分の階層がありますね - ソーシャルな階、いわゆるプライベートな階、そして屋根裏階のことです。ソーシャルな階には、片側のコーナーにいくつかの機能、もう一つのコーナーには大きなL字の形をしたリビング空間が配置されています。同じ構成がプライベートな階でも適応されていて、一つ目のコーナーにはいくつかの寝室、そしてもう一つのコーナーには大きな主寝室が配置されています。

ところが、私の解読においては、この住宅の通俗的理解 - つまりソーシャルな空間、プライベートな空間、寝室、リビング、家族のための空間、そして客のための空間など - これら私たちが日常生活を定義するために使用するあらゆる言葉が、この住宅の本当の質を理解するためには全く無関係なもので、不十分なことだとわかるでしょう。

全ての家具を図面から取り去ってしまいましょう。すると、この住宅が二つのゲームに基づくものだと理解できるでしょう。各階における主と従の空間のゲーム。外部の直角性と内部の曲面性のゲーム。これらが、各階のL字の部屋に大きな差異と相互の依存作用を作り出しているのです。部屋の角、表面、そして光の戯れが用途に関係なく、意味をなしていることに気づくでしょう。材料や構造が特別なものでないことは驚くべきことです。つまりそこには、壁、窓、天井、そして床だけしかないのです。それに全てが白塗装の合板でできています。その意味では、これは巨匠による仕事ですよ。使える道具とその制約を理解しながら本当に上手く利用しています。とにかく素晴らしい。

長谷川逸子は70年代に手がけた住宅についてのテキスト(「70年代の仕事」SD1985年4月号)の中で、意外なことに「芸術的表現のための抽象的手法よりも、むしろ生活への関心」を強調していますね。柿生の住宅は、あなたが説明されたように、生活への関心だけで作られていないことは明らかだと思われるのですが。

この世代の建築家たちは、自身の活動せざるを得ない平凡な状況に対して、多くの文章を書いています。彼らはシノハラの思想に影響を強く受けながらも、メタボリズム運動の影の中、そしてプレファブ住宅産業が台頭する中で活動を強いられたのです。どちらも規格化され、反復可能で大量生産される住宅を称賛していました。それに対して、長谷川逸子の属していたグループはみな、小さな住宅のみを扱うグランジ・キッズたちだったのです。彼らは正しいと信じているもの、そして「芸術家たるべきか、それともサービスの支給者たるべきか」というジレンマとに、格闘していたのです。これらは彼らにみな共通していたことです。

彼らの野心、感性、そして知性の蓄積。それらはシノハラの「芸術としての住宅」に触発されたものでした。ところが、ほとんどのクライアントは建築には全く興味がなく、予算も工期も限られていたのです。

長谷川逸子は、大学でシノハラのもとで働いていましたし、彼のクライアントのことを良く知っていました。彼らはたいてい社会の上流階級の人々でした。つまり彼女は二つの世界を生きていたわけです。エリート層の世界、そして日本の若い建築家が面する、ごく普通の世界。彼女は、仲間たちの多くが応えざるを得ない、このスキゾフレニックな状況を強く意識していました。実務を続けるためには、シノハラから学んだ戦略を見直さざるを得なかったのです。シノハラスクール、そしてその手法は多くの事例においては適応できないことがわかっていたからです。

長谷川逸子のキャリアは、全てこの矛盾した状況が引き金となっているのでしょう。彼女がすぐに受け入れたのは、おそらく彼女のボキャブラリーや言語で、それらがシノハラのように純粋なものであってはいけないということでした。多分、シノハラほどにはアグレッシブになれなかったのでしょう。彼女は作家としての目標を達するためにも、あるバランス、ゲーム、そしてシステムを作り出す必要がありました。

彼女は住宅が作品化することへの疑問を呈しつつも、柿生の住宅において、弾丸をひらりとかわし、雨つぶの間をすり抜けるようにして、まさにその方法を見つけ出しているのです。ほとんどポルノ的に住宅を作品化する方法を。それを誇らしげに見せるわけでもなく。

彼女の芸術的な目標とは何だったのでしょうか?

長谷川逸子は、L字の空間のことを寝室、リビングなどとは絶対に呼ばないのです。代わりに「主室1」、「主室2」と呼んでいるのです。このことから多くのことがわかりますね。サービスブロックの部屋には全て、キッチン、風呂、洗面所、寝室などの名前がついていますから。つまり、住宅は特定の用途のためにあるのではない、ということを示唆しているのです。それは、空間に関することなのです。

副次的な部屋というものは、実利的な理由で存在するものですが、結局は何が重要かをフレーミングする効用があるのです。発表された写真に、サービスブロックの中で唯一写っているのは、階段ですね。圧縮された空間を通過させるだけの基本的な装置ですが、ここでは、二階にある二つ目のL字空間へと至るまでに、一階空間での経験をほとんど忘れさせてくれるような効果があるのです。

一階のL字空間は二つに分断されています。一方にはキッチンに面してダイニングテーブルが置かれており、もう一方はいつも空っぽの状態です。どちらも写真でも出版物でも見ることができますね。ここは玄関スペースであり、通行のためのスペースでもあり、これからこの住宅が披露してくれるものに備えるための「ウォッシングルーム」だとも考えられるでしょうか。長谷川逸子は、その一角に固定式の家具をいくつか配置していますね。ここには古典的な三位一体の関係 - 玄関、リビング、ダイニングがあるのです。これらの機能は全て、サービスブロックでの行為と関連しながら合理的な感じがします。

普通の住宅では、リビングが一番大きな空間を占めますよね。しかしこの住宅では、上階の主寝室もリビングとほとんど同じ面積を占めているのです。写真でも図面でも、二階のL字空間にはシングルベッドが二つだけ、部屋の片側に配置されています。残りは空っぽのまま。L字空間のそれぞれの端には机があって、この部屋が寝るためでもあり、仕事するためでもあるということを意味しているかのようですね。他には家具はありません。

下階に対しての破滅的な片割れという感じなのでしょうか。床はとても暗いのですが、代わりに壁は全て真っ白です。扉は白い壁面に完全に溶け込むように白のフラッシュ戸で作られています。どこの窓からやってきたのかわからない自然光が、側面から現れ、それが勾配天井にあたり、曲面に影を落とす、その自然光による人工的な魅力は卓越していて素晴らしいのです。

一階では、住宅の社会的空間としてのプログラムに対する伝統主義的とも呼べるような視点に関して、非常に明快な意図がありました。

一方、二階は通常の寝室としては明らかに広すぎるので、自然と別の部屋へと変わってしまうのです。この不均衡な関係と特異性によって、長谷川逸子は、機能こそがデザインの主なモチベーションなのではなく、別の性質、別の象徴的なものがあることを示しているのです。

「象徴的」という言葉を使われましたが、それは何を指しているのでしょうか?

象徴的性質というのは、合理性と関係があると思うのです。本当に象徴的な空間や要素というものは、なぜそこにあるのか、なぜそうなのか、とあなたに考えさせてくれるのです。

日常的ではなく、分類しづらい、それでいて奇妙な魅力があるもののことです。それは、機能や技術的な説明を超えた解釈や、考えを与えてくれ、議論させてくれるものなのです。

玄関ホール、リビング、寝室、などといった観点から住宅を捉えるような古典的なやり方で、機能を考える方法は、個人的には非常に時代遅れな考え方だと思いますね。私たちは実践において、明確な実利的解答を見いだせないような配列関係を探っているのです。つまり今日、私たちがしているような刺激的な議論のきっかけとなるアンカーを探し出すためにも、曖昧で抽象的な観念を取り入れているのです。

私たちが研究していく中で、日本の事例から学んだことはまさに、現実と非現実の境界を曖昧にすること、つまりは、家に住むという固定観念を取り払い、別の選択肢を与えることの重要性なのです。私たちも、そういった事例の家族の一員となりたいと思っていますし、上手くは定義できないような「もの」を求めているのです。私たちは、それを空間や要素の象徴的、記号的性質と呼んでいるのです。

日本の建築家が、この性質に対して非常に敏感になったのはなぜだと思われますか?

それに関しては推測が可能です。日本語は、私たちが一言で表現してしまうようなことを定義するために、いくつかの記号を使いますよね。例えば、白、背景、などを定義する記号は、いくつもあるのです。ヨーロッパ的な視点からは、何もない白い背景、を理解することは非常に明快なことなのですが、日本では、どのように何もないのか、どういった白なのか、などを明らかにしておきたいのでしょう。同じことが、柱、にも当てはまります。私たちは、コラム、ポスト、ピラーなどいくつかの定義を持っていますが、それらはほとんど同じものを指しています。日本語では、柱、が何を意味するのかはその柱の位置によって様々な定義があるのです。もしそれが構造の中心に位置している場合は、特定の名称を持ちますし、外周部に位置している場合はまた別の名称を持ちます。下級建築とも呼べるような建物にある場合と、寺院のように重要な象徴的建築にある場合とでは、別の意味を持つのです。それぞれの言葉の意味を具体的に考えることは、結果的にそれぞれのモノの意味を具体的に考えることなのですが、それは日本の文化に深く根ざしていることなのです。

しかし、私が最も重要だと思うことは、この時代の建築家たちが、ある結実した成果に到達できたということだけでなく、彼ら自身が自らの作品についての理論化を途方もないほどに試みていたということなのです。これらの建築家たちはみな、いくつかの雑誌に掲載された文章の中で、自身が行っていたことを記述しています。80年代の「新建築」は毎月10万部発行されていました。宮脇檀、坂本一成、そして長谷川逸子らの論考が定期的に一般の人々の手元にも届いていたのです。一般の市民もたまには、こういったテキストを読んでいたのでしょうね。写真だけではなく膨大な情報が流布されていたのです。建築の論考があらゆる人へと届いていたのです。

現代の日本建築のマンネリ化は、そういったことがなくなってしまったことに大きく起因しているのだと思います。伊東豊雄が最後にそのような文章を書いたのも、おそらく30年も前のことでしょう。現代の日本のスターアーキテクト世代は全く異なる方向へと進んでいます。アトリエ・ワンのリサーチについて言及するにも、それはイツコの時代とは全く異なるものですよね。今日では、アトリエ・ワンのような建築家たちは、建築的空間を創造する理論よりも都市のスケールに関心を持っています。

70年代、80年代の日本の建築は、経済的、社会的事象によって生じた、ある現象で、それを支えていたのは狂気的なほどの出版物への情熱なのです。そのおかげで、全世代の建築家たちは足を止め、考え、実験し、解釈し、お互いにコミュニケーションを取り合い、それが結果として大衆へと届くこととなったのです。ミヤワキは美しい文章を書いていて、このような努力は全て世界を変えるためになされたことなのだと結論づけているのです。そこには闘志と使命感があったのです。彼らの敵はいつしかメタボリストではなく、プレファブ住宅へと変わっていきました。印象派の作家たちが写真に対抗したのと同じように、建築家たちもまた、彼らに取って代わろうとするものへ対抗するための活力が必要でした。

私たちの議論しているこの住宅が建てられた時代は、あらゆることが急速に変化した時代だったのです。土地の価格も急激に上昇していきました。いくつかの住宅はたった二、三年しか存続しなかったのですが、それも土地の価格が上昇し続けているために、すぐに買い換えることができたからなのです。建築家たちは、彼らの住宅が長く存続しないことを知っていたのです。そういった事情から、日本のクライアントたちは、より柔軟で、型にはまらない設計を許容できたのです。ヨーロッパでは、私たちは住宅を一生のものとして建ててきました。対して、彼らは10年単位で建ててきたのです。これは大きな違いです。

この現象をマクロで見ると、非常に興味深いものがあります。出版物はまさにゲームチェンジャーであったわけです。現在、日本に存在するプレファブ住宅は、40年前に建築家たちが理論化したデザインに深く影響を受けています。「カサベラ」や「ドムス」もヨーロッパでは、このようなことは、成し得ませんでした。これらの日本の出版物は、日本でのこうした状況に貢献してきたのです。

柿生の住宅に話を戻したいと思います。出版物では伝えきれなかったことがあるとすればそれは何だと思われますか?

この住宅の出版物では表現しきれなかったこと、それはこの住宅の音響的効果の探索

でしょうか。この住宅へと入っていくことを想像します。5人の人がテーブルを囲んで食事をしています。その姿は見えないですが、声は聞こえますね。夕食の時間を想像してみます。側面から自然光が入ってくる事はなく、何かしらの人工照明がテーブル近くにあるのではないでしょうか。そうすると、この白い曲面全体に人の影が映し出されるでしょう。出版物の写真は、人が住み着いたものではなく、演出されていて、これらの空間の劇的な要素が示される事はありません。

これは、アルヴァロ・シザとエドゥアルド・ソウト・デ・モウラとの間で交わされた興味深い議論のポイントでもあるのです。何年も前の事になりますが、ポルトの大学で、彼らは、海の前に建つ住宅の窓は小さい方が良いのか、それとも大きい方が良いのか、という議論をしていたのです。彼らはお互いに反対の意見を持っていました。ソウト・デ・モウラは部屋からは海全体が見えるようにすべきだと考えていたのですが、シザは、そうじゃない、海を見に行こうという気持ちにさせるためにも、窓は小さくするべきだと言ったのです。そっちの方が努力を強いるものですけどね。

この世代の日本人は、人を惹きつけ、刺激し、移動させるような仕掛けを考えていたという点で、シザの方に賛同していたでしょう。この住宅内における、影との戯れや社会的な振る舞いは、私たちが見ることのできる出版物からとは、全く異なる深い効果を持っていたと思います。

柿生の住宅は白の家と呼べるでしょうか、それとも黒の家と呼べるでしょうか?

どちらとも言えないと思います。ここでの白は、ただ付随的なものだと思います。シノハラの第二様式の住宅のようなポレミックな白ではないですよね。抽象的な白でもない。何よりも、目的のための手段なのです。年表で見てみると、柿生の住宅はシノハラの第二様式の終わりと、第三様式の始まりとの間に建てられているのです。この白はただ、そこで起きる何かに寛容な白だと思うのです。「谷川さんの住宅」においての白が、木の形をした柱や傾斜した土間を空間の主役とするようにね。

柿生の住宅においての白、そして床の暗いカーペットは必要なものだと思いますね。そのおかげで、二つの窓や、ダブルハイトの光源からやってくる光の効果が理解できるのです。

日本では、景色の見えない窓はよくあることです。敷地があまりにも狭く、光もほんの少ししか入ってきません。窓に対する固定観念を打破し、単に外をみるための装置以上のものとして窓を捉え直すためには、何が論点になると思われますか?

日本の都市のカオス、そして建築と都市の関係についてはメタボリストから藤本壮介に至るまで様々な建築家たちによって多くの理論が書かれていますね。これらの世代はいずれも、非常に密集したメタボリックな都市の状況を扱っていますし、そのほとんどにおいて採光と換気の必要性から窓をデザインしているのです。その窓から何が見えるのか、ということではなく、です。

窓は、ある住宅とある場所を結びつける数少ない要素の一つですが、この世代の建築家たちはそれを望んではいなかったのです。

柿生の住宅の窓の写真においては、窓は燃えてしまったように - つまり窓の外はただ白くなっているだけなのです。これは、シノハラが理論化した住宅の自律性に対しての別の表現なのです。住宅には敷地がなく、コンテクストにも属さず、どこにでも存在し得る、という自律性です。もし窓から景色が見えないのであれば、その意図については語らざるを得ないでしょう。

柿生の住宅では、曲面の壁に穿たれた窓が、一階の主室に自然光をもたらしている外壁の窓と向かい合っているわけですが、長谷川逸子は、その角度によって、両方の窓から同時に外を見通すようなことができるかどうかなど気にしていなかったのだと思います。それが主題では全くないですからね。

窓は全て正方形で、完璧にフレーミングされています。この住宅と、それを取り囲むコンテクストを繋ぎ止める事実上のアンカーとしてではなく、むしろ壁に描かれた絵画のようなものなのです。

この住宅を別の用途として使う事は想定できますか?この住宅を自分のものにしたいと夢見るような事はありますか?

主室にベッドを置くことはまずないでしょうね。サービス部分に配置すると思います。上階は仕事をする空間、そして下階は人との関わりを持つような空間とするでしょうか。例えばですが。二つの主室は、夏の部屋と冬の部屋、あるいは読書する空間と、仕事をしたり音楽を聴く空間でもいいでしょう。L字の空間はただ寝るだけの部屋としては強すぎると思うのです。そこは、別の次元、象徴的な次元へと外挿されるような性質や特徴を持っているのです。まったく空っぽなその空間をたまに通り過ぎていく、そのような事はイメージできますけどね。シノハラの第二様式における亀裂の空間的な質があると思います。そこは椅子をおいておけばそれで十分な空間ですよね。

私にとって、この住宅の最大の挑発的主張は、写真や図面に示された二つのマットレスなのです。二つのベッドをそこに置くことで、長谷川逸子は「サービスの提供者と芸術家との間のジレンマ」を貫いているのだと思います。これが私のせざるを得なかった事であり、やりたいことのために、ここまでやってきたのだ、と彼女は言っているのです。

柿生の住宅に対して、不思議に思うところはありますか?

柿生の住宅が建てられたころ、シノハラは上原通りの住宅や谷川さんの住宅を手がけていました。彼は構造や象徴的な構造物と戯れていたのです。長谷川逸子も空間を作るために構造を利用した住宅を作っていました。例えば、焼津の住宅2がありますね - それは構造が住宅であり、またその逆でもあるのです。ところが柿生の住宅においては、構造が非常にうまく隠蔽されています。梁や柱がどこにあるのかわからないでしょう。ある瞬間を除いては。それは屋根裏から撮られた一枚の写真にあるのです - 全ての面材の収束点に柱があり、その柱は屋根に触れているのです。他の階からは、その姿が見えることはありません。言及もされていませんし、そのことを示すものも何もありません。長谷川逸子は、その具体的な写真を一枚、海外の出版物に掲載したのです。柱の姿が現れる、ほとんど知覚不可能な瞬間を、彼女は何らかの理由で外部に公開しようと決断したのです。構造の配置計画や表現が価値を持ち得た時代に、彼女は、住宅の中で、最も重要度が低く、最もアクセスしづらい空間にだけ、その柱の姿を暴露させていたわけです。そのことが、私に問いかけてくるのです。彼女はそのとき一体何を考えていたのだろうか、と。

2021年9月18日

Filipe Magalhães: The limbo in which we, fala, operate - between the lack of interest of the client and the excess of ambition and enthusiasm on our side - is very similar to the situation Itsuko Hasegawa was confronted with, while designing her first houses in the 70s.

YOU PUBLISHED THE DRAWINGS AND PHOTOS OF THE HOUSE IN KAKIO IN YOUR RECENT BOOK ON JAPANESE HOUSES. FROM ALL THE BUILDINGS YOU ANALYSED, WHAT MADE YOU MAKE THIS CHOICE?

It is a house built with very little resources. It’s a banal construction of a boring brief. It’s a discrete, cheap, suburban house. However, the discrepancy between what we could call a very unappealing exterior and a phenomenal interior composition - not in a tectonic sense, but in a spatial and symbolic sense, is surprising. It is almost as if Itsuko designed a house that disappears from the outside on purpose, in order to protect the treasure that hides within.

It has two and a half levels - a social level, a so-called private level, and an attic level. The social level has some program in one corner and a big L - shaped living room in the other corner. The same structure applies to the private level, with some bedrooms in the first corner and a big master bedroom in the second corner.

My reading, however, tells me that the conventional understanding of this house - a social part, a private part, a bedroom, a living room, a space for family members, a space for guests - all these words that we usually use to define the daily life of a house, turn out to be completely irrelevant and insufficient to grasp the real quality present.

If you take all the furniture away from the plans, you end up with a house based on two games - a game between the main and the secondary spaces on each level, and a game between the outside rectangular shape and the inside curved shape, which create important differences and interdependence in the L-shaped rooms on each level. You discover a play of angles, surfaces and light that make sense, independent of any use. It is remarkable that there are no material or structural special effects: there are just walls, windows, ceilings, and floors. Everything is out of white painted plywood. In this sense, it is the work of a master, whereby she truly understood the tools and limitations present and used them only to her advantage. All this is just fantastic.

IN THE TEXT ITSUKO HASEGAWA WROTE ABOUT THE HOUSES SHE BUILT IN THE 70’ („MY WORK OF THE SEVENTIES” IN SD 04/85) SHE SURPRISINGLY UNDERLINES HER INTEREST IN „THE CONCERNS OF LIVING RATHER THAN ABSTRACT METHODS OF ARTISTIC EXPRESSION”. THE HOUSE IN KAKIO, AS YOU STARTED TO EXPLAIN, IS DEFINITELY NOT ONLY ABOUT THE „CONCERNS OF LIVING”.

This entire generation wrote a lot about the mundane conditions in which they had to operate. Although they were strongly influenced by the ideas of Shinohara, they had to work in the shadow of the Metabolist movement and the emerging prefab house industry. Both praised standardised, repetitive dwellings, produced in huge quantities. The group Itsuko Hasegawa belonged to, were the grunge kids, the ones that had only tiny houses to deal with. They struggled a lot for what they believed was right and with the dilemma: „should we even try to be artists or should we be service providers” was very present in all of them.

Their ambitions, sensibilities and intellectual preparation were inspired by Shinohara’s „house as a work of art”, but their clients were very often not at all interested in architecture, had limited budgets, and tight schedules.

Itsuko Hasegawa worked for Shinohara at the university and knew his clients, who usually came from the higher layers of the society. She was living in both worlds - the elite, and the ordinary reality of a young architect in Japan. She was very conscious of the schizophrenic situation many of her colleagues had to find an answer to. To remain in practice, they were forced to rethink the strategies learned from Shinohara, as his school and methods turned out to be impossible to apply in the majority of cases.

Everything that came to happen in Itsuko Hasegawa’s career was triggered by this contradiction. What she quickly accepted was that maybe her vocabulary, her language, could not be as pure as Shinohara’s. Maybe she could not be as aggressive as he was. She had to create a certain balance, invent games and systems in order to achieve her goals as an author.

Even though she wrote about her doubts on the possibility of a house being a work of art, in Kakio she dodged the bullets, walked between the drops of rain, and found a way to do exactly that, almost pornographically making a house a work of art - without even boasting about it.

WHAT WAS HER ARTISTIC GOAL?

Itsuko Hasegawa never calls the L-shaped spaces bedroom and living room. Instead, she calls them „main room one” and „main room two.” This tells us a lot, because the rooms in the service block, all have names like kitchen, bathroom, washroom, or bedroom. L-rooms remain „main rooms”. It suggests that a house is not about specific uses. It is about space.

Secondary rooms are there for pragmatic reasons and eventually help to frame what is important. The only published picture of the service block is the staircase - a fundamental device to force you to go through a compressed space, and makes you almost forget the experience you had at ground floor before accessing the second L-shaped space on the first floor.

The ground floor L-shape room is divided in two. There’s a side with a dining table, facing the kitchen and the other which is always empty, both in photos and publications. You assume it to be the entrance space, a space to pass through, a kind of „washing room” where you get ready for what the house is going to reveal to you. In the corner, Itsuko Hasegawa designed a few pieces of fixed furniture. We have a classic triad - entrance, living, dining. All these functions are related to what happens in the service block and have a reasonable surface.

In a normal house, the living room is the biggest space. In this house, the upstairs master bedroom is almost the same area. Both in photos and drawings, the first floor L-shaped space is furnished with only two single beds, orientated on one side of the room. The rest of the room is just empty. At the end of each side of the L-shape, there is a desk, as if this space was meant for both sleeping and working. There is no other furniture. It is a kind of subversive twin of the room below. The floor is very dark, but all the walls are white. The doors have flush white frames ready to fully melt into the white wall surface. The plastic appeal of the natural light, that comes from windows not immediately visible, appears from the side, and hits the pitched ceiling, casting a shadow on the curve, is outstanding.

At ground floor, she had a very clear intention regarding what we can call a traditionalist perspective on program in the social space of a house.

Upstairs instead, there is clearly too much area for a standard bedroom, so the room automatically becomes something else. Thanks to this disproportion and peculiarity Itsuko Hasegawa demonstrates that function it is not the main motivation in her design, but something of another nature, something symbolic.

YOU USE THE WORD „SYMBOLIC” IN REGARD TO SPACE. WHAT DO YOU REFER TO?

I think the symbolic aspect has to do with rationality. A truly symbolic space or element puts you in a position to wonder why it is there, and why like this? It has an appeal of something out of ordinary, not easy to classify, a bit strange. It makes you interpret, think and discuss beyond the functional or technical descriptions.

As far as I am concerned, the way of thinking about functions in the classical sense, in which we think of a house in terms of an entrance hall, a living room, a bedroom, etc. is a very outdated perspective. In our practice we are looking for arrangements in which it is impossible to discern clear pragmatic answers. We introduce vague, abstract notions in order to find an anchor that will trigger some sort of inspired discussion - like the one we are having today.

What the Japanese references showed us during our research, was exactly the importance of blurring the boundaries between the real and the unreal in the sense of giving an alternative, deconstructing the stereotypes about how to live in a house. We want to be part of this family and look for the „thing” that we don’t know how to define very well. We call it a symbolic, or semiotic quality of space and elements.

WHAT DO YOU THINK PUSHED JAPANESE ARCHITECTS TO BECOME EXTRAORDINARILY SENSITIVE TO THIS QUALITY?

We can speculate on that. Japanese language has several symbols to define what we describe with one word. They have several symbols to define white, background etc. Understanding an empty white background from an European perspective is pretty clear, in Japan they would want to clarify how empty, which white, etc. The same thing applies to a column. We have words like column, post, pillar - a few definitions that pretty much refer to the same thing. The Japanese have numerous definitions for what a column means, depending on its position. If it’s in the centre of a structure, it has a specific name, if it’s on the perimeter, it has another If it is in what we could call a low-class building, it has a certain sense, if it is an important symbolic building, like a temple, it has another. It is deeply rooted in Japanese culture to be specific about the meaning of each word and as a consequence of each object.

However, what I believe to be the most important factor is that in this period architects not only intimately arrived at certain conclusions, but also theorised tremendously about their own work. All of these architects wrote and depicted what they were doing in texts published in several magazines. Shinkenchiku in the 80’ had a circulation of one hundred thousand prints every month. The general population was receiving theory from Mayumi Miyawaki, Kazunari Sakamoto and Itsuko Hasegawa among others at regular intervals. An ordinary citizen would probably read one of these texts once in a while. There was a huge diffusion of information that was not just photographic. Architectural theory was reaching everyone.

To a large extent, I think, the cliche of contemporary Japanese architecture, comes from the fact that this does not happen anymore. Last time Toyo Ito wrote a relevant text was probably 30 years ago. The current generation of star architects in Japan have moved in a very different direction. Even if you mention the research of Atelier Bow Wow, it is very different from what happened in Itsuko’s times. Nowadays, architects like Bow Wow are more interested in the urban scale than in the theory of architectural space making.

Japanese Architecture in the 70’s and 80’s was a moment created by economic and social issues which were then supported by an insanely intense publication frenzy, that in turn allowed a whole generation of architects to stop, think, experiment, read, communicate with each other and consequently, reach the masses. Miyawaki wrote a beautiful text, concluding, that all this effort was aimed at changing the world. There was a combat spirit and a mission. Their enemies at some point stopped being the Metabolists and started to be prefab houses. Similarly, to the impressionists who had to fight photography, architects had to find the energy to fight back, as something was trying to replace them.

The period in which the house we are discussing was built was a period when everything was happening very fast. The price of land was increasing drastically. Some of these houses lasted just a couple of years because the ever-increasing price of land meant they could be replaced right away. The architects knew that their houses were not meant to last. All this allowed Japanese clients to be a bit more flexible and allow more unconventional layouts. In Europe we built for a lifetime. They built for a decade. This makes a huge difference.

It’s very interesting to look at this phenomenon at a macro scale. The publications were really a game changer. Today, the prefab housing that still exists in Japan is deeply influenced by the design these architects theorised 40 years ago. Neither Casabella nor Domus managed to do that in Europe. All of these Japanese publications were contributing to this in Japan.

COMING BACK TO THE HOUSE IN KAKIO, WHAT DO YOU THINK WAS NOT POSSIBLE TO TRANSMIT IN PRESS?

There’s something that the publications of the house never managed to do, which was to explore the acoustic aspect of the house. If you imagine that you just entered, and there are five people having a dinner where the table is drawn, you don’t see them, but you hear them. And if you assume it’s a dinner time, you probably don’t have the natural light coming from the sides, you have some sort of artificial light near the table. You’re going to see the shadows of these people spread all over this white curved surface. In the publications the photos are never inhabited, they are staged and do not show the dynamic components of these spaces.

This is also an interesting point of discussion between Alvaro Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura. Many years ago, at the school in Porto, they were debating if a house in front of the sea, should have a small window or a big window. They disagreed. Souto de Moura felt you should see the whole sea from the room. Siza instead said, no, you should make it small so that people are motivated to go to see the sea. It needs to become something you have to make an effort for.

I would say this Japanese generation agreed with Siza, thinking in terms of hints that attract and provoke you to make you move. I think the play of shadows and the social behaviour inside this house would have a profound effect, very different from what we see published.

WOULD YOU CALL THE HOUSE IN KAKIO A WHITE HOUSE OR A BLACK HOUSE?

I wouldn’t call it either. I think the white here is just circumstantial. It’s not a polemic white like the second style houses of Shinohara. It’s not an abstract white. More than anything else, it’s a means to an end. If you look at it in a timeline, the house in Kakio is built between the end of the second style of Shinohara and the beginning of the third style. I think this white is a white that just liberates something to happen, like in Tanikawa house, where the white makes the tree shaped columns and the sloped earth floor the protagonists of the space.

I think the white in Kakio and the dark carpet on the floor are necessary, so that you understand the light effects coming from two windows and the double height light source on the ground floor.

IN JAPAN, OFTEN YOU HAVE A WINDOW THAT DOESN’T HAVE A VIEW, IT GIVES ONLY A LITTLE BIT OF LIGHT BECAUSE THE LOTS ARE SO TIGHT. WHAT DO YOU THINK MIGHT BE AN ARGUMENT TO DESTROY THE COMMON STEREOTYPE OF A WINDOW AND CONCEIVE IT AS SOMETHING OTHER THAN A DEVICE TO PURELY LOOK OUT OF?

There’s a lot of theory about urban chaos of Japan and the relationship between architecture and the city written by different architects from the Metabolists to Sou Fujimoto. All of these generations were dealing with the very dense, metabolic urban condition and most often they designed windows just because the building needed to have them for light and ventilation, not because of whatever the window was going to reveal.

A window is one of the few elements that links a specific house to its specific place. The architects of this generation didn’t want it.

The photos of the windows in the house in Kakio, show them burned - the outside becomes just white. It’s another way of speaking about the autonomy of a house theorised by Shinohara - the house has no site, it does not belong to the context, it can be anywhere. If a window doesn’t give you a view it certainly helps to speak about this intention.

In house in Kakio the windows cut in the curved wall are facing the window in the outside wall, that gives some natural light to the main room in the groundfloor. However, I don’t think that Itsuko Hasegawa cared if the angle allowed a person to see through both windows at the same time. That’s not the topic at all.

All of the windows are squares, perfectly framed. They are more like paintings on the wall rather than actual anchors to the context that surrounds the house.

IS THERE ANY WAY IN WHICH YOU WOULD USE THIS HOUSE DIFFERENTLY? DO YOU HAVE SOME KIND OF DREAM OF HOW YOU WOULD MAKE THIS HOUSE YOUR OWN?

I wouldn’t put my bed in any of the main spaces. I would probably place it in the service part, and I could imagine the top level to be the space where I work, and the bottom level the space where I relate with other people, for example. Two main rooms could be for instance a room for the summertime and the room for the winter or a space to read and a space to work or to listen to music. I think the L-shaped rooms are too intense to just sleep in them. I think they have qualities and characteristics that extrapolate them to another level, a symbolic one. I could imagine them to be completely empty and just to walk through them once in a while. They have the fissure space quality of Shinohara’s second style houses, where you put a chair and it’s enough.

To me, the biggest provocations in this house are those two mattresses in the photos and plans. By putting the two beds there, I think, Itsuko Hasegawa is poking the „service provider versus artist” dilemma. She’s saying - “this is what I had to do: look how far I went to achieve what I wanted”.

IS THERE SOMETHING THAT REMAINS FOR YOU A MISTERY IN THE HOUSE IN KAKIO?

At the time when house in Kakio was built, Shinohara was working on Uehara House and Tanikawa House. He played with structure, symbolic structure. Itsuko Hasegawa also made houses that used structure to create spaces, for example, the house in Yaizu 2 - the structure is the house and vice versa. However, House in Kakio is one where the structure is pretty much disguised. You don’t know where the beams or columns are, except for one very specific moment, you can only see in one photo from the attic space - there is a column that appears and touches the roof in the point of convergence of all the surfaces. It doesn’t show up in the other levels. There’s no writing, nothing that refers to it. Itsuko Hasegawa published one specific photo of it in an international publication. She decided for some reason to reveal to the outside world that almost unperceiveble moment where the column appears. In the time when the positioning of structure and the expression of structure was so relevant, she reveals it only in the least important, and most difficult to access space. It leaves me wondering, what was she thinking about.

18.09.2021

菲利普・麦哲伦:我们Fala工作室这种,在甲方兴趣的缺乏,和我们雄心和热情的过度中运作的处境,和长谷川逸子在70年代设计她的第一批住宅时遇到的情况非常相似。

你在最近出版的《日本住宅》一书中发表了柿生的住宅的图纸和照片。在你分析的所有建筑中,是什么让你做出了这个选择?

这是一个用极少的资源建造的住宅。它是一个无聊指示下的平庸构筑物,一个离散的、廉价的、郊区的住宅。然而,在相当不讨喜的外观和惊人的内部构成之间形成的差异——不是在建构意义上,而是在空间和象征意义上——是令人惊讶的。这几乎就像长谷川逸子故意设计了一个消失于外界的住宅,以保护隐藏在内的珍宝。

它有两层半——一个社交层,一个所谓的私人层,以及一个阁楼层。社交层的一角有一些功能,另一角有一个L型的大起居室。同样的结构适用于私人层,第一个角落有一些卧室,第二个角落有一个大的主卧。

然而,我从中读到的是,对这所住宅的传统理解——社交部分、私人部分、卧室、起居室、家庭成员的空间、客人的空间——所有这些我们通常用来定义住宅日常生活的词,结果是毫不相关且不足以去把握这个住宅真正呈现出来的品质。

如果从平面图上拿掉所有家具,你会得到一所基于两个游戏的住宅——每一层的主要空间和次要空间之间的游戏,以及外部矩形和内部曲线之间的游戏,这在每一层的L形房间中创造了重要的差异和依存。你会发现角度、表面和光线的把玩是有意义的,与任何用途无关。值得注意的是,这里没有任何材料或结构上的特殊效果:只有墙壁、窗户、天花和地板。所有东西都是用刷白的胶合板制成的。在这个意义上,它是一个大师的作品,在此她真正理解目前的工具和限制,并只使用它们来发挥她的优势。所有这一切都很精彩。

在长谷川逸子写的关于她在七十年代建造的住宅的文章中(“我的七十年代作品”,载于SD 04/85),她令人惊讶地强调了她对 “生活的关注而不是抽象的艺术表达方法 “的兴趣。柿生的住宅,在你开始的解释中,绝对不仅仅是在于 “生活的关注”。

这整整一代人写了很多文章关于世俗的状况,他们必须运作于其中。尽管他们受到筱原思想的强烈影响,但他们不得不在新陈代谢运动和新兴的预制房屋行业的阴影下工作。两者都推崇标准化的、重复性的住宅,并大量生产。长谷川逸子所属的群体是颓废派(grunge)的小孩,那些只有小房子可以处理的人。他们为自己认为正确的事情做了很多挣扎,并陷入两难境地:”我们应该甚至尝试成为艺术家,还是应该成为服务提供者”,这在他们所有人身上都很常见。

他们的雄心壮志、情感和智识准备都受到筱原 “作为艺术作品的住宅 “的启发,但他们的客户往往对建筑一点都不感兴趣,预算有限,时间紧迫。

长谷川逸子在大学里为筱原工作,认识他的客户,他们通常来自于上流社会。她生活在两个世界里——精英阶层,以及日本年轻建筑师的普通现实。她非常清楚她的许多同侪必须找到对这种精神分裂的状况的答案。为了保持实践,他们不得不重新思考从筱原那里学到的策略,因为他的学派和方法在大多数情况下都无法适用。

长谷川逸子职业生涯中发生的一切,都是由这个矛盾引发的。她很快接受的是,也许她的词汇,她的语言,不可能像筱原那样纯粹。也许她不能像他那样积极进取。她必须建立某种平衡,创造游戏和系统,以实现她作为一个作家的目标。

尽管她在书中写道,她对房子成为艺术品的可能性表示怀疑,但在柿生的住宅中,她躲过了子弹,在雨滴间行走,并找到了一种方法,几乎像情色画般地将房子变成了艺术品——甚至没有对此夸夸其谈。

她的艺术目标是什么?

长谷川逸子从未将L型空间称为卧室和起居室。相反,她称它们为 “主房间一 “和 “主房间二”。这告诉我们很多,因为服务区的房间,都有厨房、浴室、盥洗室或卧室这类名称。L型房间仍然是 “主要房间”。这表明,住宅不是关于具体的用途。它是关于空间的。

次要房间的存在是出于实用的原因,并最终帮助框定重要的东西。服务区唯一公布的照片是楼梯——一个迫使你穿过压缩空间的基本设施,并使你几乎忘记了在进入二楼第二个L形空间之前在一楼的经历。

一楼的L型房间被一分为二。一边是餐桌,面向厨房,另一边在照片和出版物中都是空的。你假设它是入口空间,一个通过的空间,一种 “洗涤室”,在那里你为住宅将要呈现给你的东西做好准备。在角落里,长谷川逸子设计了几件固定的家具。我们有一个经典的三要素——入口、起居、餐厅。所有这些功能都与在服务体块内发生的事情有关,并且有一个合理的完成面。

在普通的住宅里,起居室是最大的空间。而在这所住宅中,楼上的主卧室几乎是相同的面积。在照片和图纸中,二楼的L形空间只布置了两张单人床,放在房间的一侧。房间的其余部分都是空的。在L型的每一侧的尽头,都有一张书桌,似乎这个空间既是用来睡觉的,也是用来工作的。没有其他家具。它是下面房间的一种颠覆性的孪生。地板很暗,但所有的墙壁都是白色的。门有着齐平的白色门框,妥帖的融化在白色的墙面上。可塑性很强的自然光,源自无法立即可见的窗户,从侧面显现,打在倾斜的天花板上,在曲面上落下投影,非常卓越。

在一楼,她有一个非常明确的意图,从所谓传统主义的视野出发,对住宅的社交空间进行编排。

而在楼上,对于一个标准的卧室来说,显然面积太大,所以房间自动成为了其他什么。得益于这种不相称和特殊性,长谷川逸子表明,功能不是她设计的主要动机,而是一些其他性质的东西,象征性的事物。

你在谈到空间时使用了 "象征性 "一词。你指的是什么?

我认为象征性的层面与合理性有关。一个真正的象征性的空间或元素让你想知道它为什么在那里,为什么是这样的?它有一种超乎寻常的吸引力,不容易分类,有点奇怪。它使你在功能或技术描述之外进行解释、思考和讨论。

就我而言,古典意义上从功能来思考的方式,即我们从入口大厅、起居室、卧室等方面来思考一所住宅,是一种非常过时的观点。在实践中,我们在寻找布局,其中不可能辨别出明确的实用性答案。我们引入模糊的、抽象的概念,以便找到一个锚,引发某种启发式的讨论——就像我们今天这样。

在我们的研究中,日本的案例向我们展示的,正是模糊真实和非真实之间界限的重要性,在这个意义上给出选择,解构了关于如何生活在一个住宅里的刻板观念。我们想成为这个家族的一部分,寻找我们不知道如何准确定义的“东西”。我们称之为空间和元素的象征性的,或符号学的品质。

你认为是什么推动了日本建筑师对这种品质变得异常敏感?

我们可以对此进行推测。日语有好几个字符来定义我们用一个词描述的东西。他们有一些字符来定义白色、背景等。从欧洲的角度理解一个空的白色背景是很清楚的,在日本,他们会想澄清如何空,哪种白色等等。同样的事情也适用于柱子,我们有像column,post,pillar这样的词——几个释义几乎指的是同一件事。日本人对柱子意味着什么有许多界定,这取决于它的位置。如果它在一个结构的中心,它有一个特定的名称,如果它在周边,它有另一个。如果它在所谓低级别的建筑中,它有某种定义,如果它是一个重要的象征性建筑,如寺庙,它有另一个。对每个词的意义以及作为每个物体的结果,它在日本文化中是根深蒂固的。

然而,我认为最重要的因素是,在这个时期,建筑师们不仅密切地得出了某些结论,而且还对自己的成果进行了巨大的理论化工作。所有这些建筑师都在一些杂志上发表文章,描述他们正在做的事情。80年代的《新建筑》每月有十万份的发行量。普通民众定期收到宮胁檀、坂本一成和长谷川逸子等人的理论。一个普通公民可能偶尔会读到其中的一篇文章。这有着一个巨大的信息扩散,不仅仅是影像的问题。建筑理论在当时普及到了每个人。

在很大程度上,我认为,当代日本建筑的陈词滥调,源自于于这种情况不再发生了。上一次伊东丰雄写相关的文章可能是在30年前了。日本这一代的明星建筑师已经朝着一个非常不同的方向发展。即使你提到犬吠工作所(Atelier Bow Wow)的研究,也与逸子时代的情况大不相同。现在,像犬吠工作室这样的建筑师对城市尺度更感兴趣,而不是建筑空间制作的理论。

70年代和80年代的日本建筑处于一个由经济和社会议题创造的时刻,然后由疯狂的出版狂潮支持,这反过来又让整整一代的建筑师停下来,思考,实验,阅读,相互交流,从而抵达大众。宫胁写了一篇漂亮的文章,结论是,所有这些努力都是为了改变世界。有一种战斗精神和使命感。他们的敌人在某种程度上不再是新陈代谢主义,而开始是预制住宅。类似于印象派必须与摄影作斗争,建筑师必须找到能量来反击,因为有些东西正试图取代他们。

我们讨论的这所住宅的建造时期是一个一切都发生得非常快的时期。土地的价格在急剧上升。有些住宅只留存了几年,因为不断上涨的土地价格意味着它们可以马上被取代。建筑师们知道,他们的住宅并不意在持久。所有这些使得日本业主可以更灵活一些,允许更多非常规的布局。在欧洲,我们的建筑为一生而建。他们是以十年为单位而建的。这就有了巨大的区别。

从宏观上看这种现象是非常有趣的。这些出版物确实改变了游戏规则。今天,在日本仍然存在的预制房屋设计深受这些建筑师40年前的理论的影响。在欧洲,Casabella和Domus都没能做到这一点。所有这些日本出版物都对日本的这一切做出了贡献。

回到柿生的住宅,你认为有什么是无法在媒体上传播的?

有一件事是住宅的出版物无法做到的,那就是探索住宅的声学层面。如果你想象你一进入,有五个人正在描绘餐桌的位置吃饭,你看不到,但能听到他们。而你假设这是晚餐时间,可能没有自然光从侧面射来,你在桌子附近有某种人造光。你会看到这些人的影子遍布在这个白色的弧形曲面上。在出版物中,这些照片里从来没有人居住,它们是布景式的,没有显示出这些空间的动态成分。

这也是阿尔瓦罗-西扎和艾德瓦尔多客苏托客德客莫拉讨论的一个有趣的点。许多年前,在波尔图的学校里,他们争论于,在海边的住宅应该有一个小窗户还是一个大窗户。他们意见不一。苏托-德-莫拉认为你应该从房间里看到整个大海。西扎却说,不,你应该把它弄小,这样人们才会有动力去看海。它需要成为你必须努力去做的事情。

我想说的是,这一代日本人同意西扎的观点,考虑用暗示来吸引和激发你,使你行动。我认为这所住宅中对影子和社会行为的把玩会产生强烈的效果,与我们在出版物中看到的非常不同。

你会将柿生的住宅称为是白住宅还是黑住宅?

两个我都不会说。我认为这里的白色只是间接的。它不像筱原第二样式住宅那样的论战性(polemic)的白色,这不是一种抽象的白色。更重要的是,它是达到目的的一种手段。如果你从时间轴上看,柿生的住宅是建造于筱原第二样式结束和第三样式开始之间。我认为这种白色解放了一些事物的发生,就像在谷川之家里,白色使树形的柱子和倾斜的夯土地面成为空间的主角。

我认为柿生的住宅的白色和地面上的深色地毯是必要的,这样你就能理解一楼中来自两个窗户和通高的光源的光线效果。

在日本,通常你有一个没有风景的窗户,它只提供一点点的光线,因为地块非常狭窄。你认为有什么理由能打破窗户的常规刻板观念,把它构想为一个单纯看室外的设施以外的东西?

有很多关于日本城市乱象的理论,以及从新陈代谢派到藤本壮介的一系列不同建筑师写的建筑与城市的关系。所有这几代人都在处理非常密集的、新陈代谢着的城市状况,大多数情况下,他们设计窗户只是因为建筑需要有窗户来采光和通风,而不是因为窗户会揭示出什么。

窗户是为数不多的将特定房屋与特定地点联系起来的元素之一。这一代的建筑师们并不希望如此。

柿生的住宅中窗户的照片显示它们被销毁了——外面变得只是白色。这是谈论筱原理论中住宅的自主性的另一种方式——这个住宅没有基地,它不属于文脉(context)中,它可以在任何地方。如果一个窗户不给你视野,这当然有助于谈论这个意图。

在柿生的住宅里,在弧形墙上开的窗户正对着外墙的窗户,这给底层的主要房间带来了一些自然光。然而,我认为长谷川逸子并不关心这个角度是否能让人同时看到两个窗户,这完全不是议题。

所有的窗户都是方形的,有完美的窗框。它们更像是墙上的画,而不是实际连接周边文脉的锚点。

你会有什么不同的方式使用这所住宅吗?你是否有某种使这所住宅成为自己的住宅的梦想?

我不会把我的床放在任何一个主要空间里。我可能会把它放在服务部分,我可以想象顶层是我工作的空间,而底层是我与其他人相处的空间,比如说。两个主要的房间可以是例如夏天的房间和冬天的房间,或者一个阅读的空间和一个工作的空间或听音乐的空间。我认为L型房间太有张力了,不能只在里面睡觉。我认为它们拥有的品质和特点,将其推到另一个层次,一个象征性的层次。我可以想象它们是完全空的,我只是偶尔走过。它们有筱原的第二样式住宅中龟裂空间(fissure space)的品质,在那里你放一把椅子就够了。

对我来说,这所住宅里最大的挑战是照片和图纸上的那两张床垫。通过把这两张床放在那里,我认为长谷川逸子是在挑衅 "服务提供者vs艺术家 "的困境。她在说——"这是我必须做的:看看我为了实现我想要的东西走了多远"。

在柿生的住宅中有什么东西对你来说仍然是个谜吗?

在柿生的住宅被建造的时候,筱原正在建造上原通住宅和谷川之家。他把玩的是结构,象征性的结构。长谷川逸子也做了一些用结构来创造空间的房子,例如,焼津的住宅2——结构就是住宅,反之亦然。然而,柿生的住宅是一个结构被隐藏得很好的作品。你不知道梁或柱子在哪里,除了一个非常特殊的瞬间,你只能从阁楼里的一张照片中看到——在所有表面的交汇点,有一根柱子出现并接触到屋顶。它没有出现在其他表面。没有任何文字,或其他东西提到它。长谷川逸子在一份国际出版物上发表了它的一张具体照片。出于某种原因,她决定向外界展示这个柱子出现的几乎难以察觉的时刻。在结构的定位和结构的表达如此相关的时代,她只在最不重要的、最难进入的空间揭示了它。这让我好奇,她到底在想什么。

2021年9月18日

フィリップ・マガリャインシュ: 私たちファラの活動は、辺獄にあるのです - つまりクライアントの無関心と私たちサイドの過剰な野心や熱意との狭間 - ということですが。それは長谷川逸子が70年代に初めて住宅を設計した時の状況と非常に良く似ているでしょう。

あなたの最近出版された日本の住宅に関する本には、柿生の住宅の図面と写真が載っていますよね。そこで分析された住宅の中から、柿生の住宅を今回選ばれた理由は何なのでしょうか?

この住宅は、非常に経済的に作られています。ありきたりな要望による平凡な建設物。中心地から離れた郊外の安価な住宅。ところが、至極平凡とも言えるような外観とフェノメナルな内部構成との不一致 - テクトニックな意味ではなく、空間的そして象徴的な意味でのですが - は驚きですね。イツコは、この住宅の内部に隠された秘宝を守るために、外からの存在感をわざと消すように設計しているように思えるのです。

この住宅には二つと半分の階層がありますね - ソーシャルな階、いわゆるプライベートな階、そして屋根裏階のことです。ソーシャルな階には、片側のコーナーにいくつかの機能、もう一つのコーナーには大きなL字の形をしたリビング空間が配置されています。同じ構成がプライベートな階でも適応されていて、一つ目のコーナーにはいくつかの寝室、そしてもう一つのコーナーには大きな主寝室が配置されています。

ところが、私の解読においては、この住宅の通俗的理解 - つまりソーシャルな空間、プライベートな空間、寝室、リビング、家族のための空間、そして客のための空間など - これら私たちが日常生活を定義するために使用するあらゆる言葉が、この住宅の本当の質を理解するためには全く無関係なもので、不十分なことだとわかるでしょう。

全ての家具を図面から取り去ってしまいましょう。すると、この住宅が二つのゲームに基づくものだと理解できるでしょう。各階における主と従の空間のゲーム。外部の直角性と内部の曲面性のゲーム。これらが、各階のL字の部屋に大きな差異と相互の依存作用を作り出しているのです。部屋の角、表面、そして光の戯れが用途に関係なく、意味をなしていることに気づくでしょう。材料や構造が特別なものでないことは驚くべきことです。つまりそこには、壁、窓、天井、そして床だけしかないのです。それに全てが白塗装の合板でできています。その意味では、これは巨匠による仕事ですよ。使える道具とその制約を理解しながら本当に上手く利用しています。とにかく素晴らしい。

長谷川逸子は70年代に手がけた住宅についてのテキスト(「70年代の仕事」SD1985年4月号)の中で、意外なことに「芸術的表現のための抽象的手法よりも、むしろ生活への関心」を強調していますね。柿生の住宅は、あなたが説明されたように、生活への関心だけで作られていないことは明らかだと思われるのですが。

この世代の建築家たちは、自身の活動せざるを得ない平凡な状況に対して、多くの文章を書いています。彼らはシノハラの思想に影響を強く受けながらも、メタボリズム運動の影の中、そしてプレファブ住宅産業が台頭する中で活動を強いられたのです。どちらも規格化され、反復可能で大量生産される住宅を称賛していました。それに対して、長谷川逸子の属していたグループはみな、小さな住宅のみを扱うグランジ・キッズたちだったのです。彼らは正しいと信じているもの、そして「芸術家たるべきか、それともサービスの支給者たるべきか」というジレンマとに、格闘していたのです。これらは彼らにみな共通していたことです。

彼らの野心、感性、そして知性の蓄積。それらはシノハラの「芸術としての住宅」に触発されたものでした。ところが、ほとんどのクライアントは建築には全く興味がなく、予算も工期も限られていたのです。

長谷川逸子は、大学でシノハラのもとで働いていましたし、彼のクライアントのことを良く知っていました。彼らはたいてい社会の上流階級の人々でした。つまり彼女は二つの世界を生きていたわけです。エリート層の世界、そして日本の若い建築家が面する、ごく普通の世界。彼女は、仲間たちの多くが応えざるを得ない、このスキゾフレニックな状況を強く意識していました。実務を続けるためには、シノハラから学んだ戦略を見直さざるを得なかったのです。シノハラスクール、そしてその手法は多くの事例においては適応できないことがわかっていたからです。

長谷川逸子のキャリアは、全てこの矛盾した状況が引き金となっているのでしょう。彼女がすぐに受け入れたのは、おそらく彼女のボキャブラリーや言語で、それらがシノハラのように純粋なものであってはいけないということでした。多分、シノハラほどにはアグレッシブになれなかったのでしょう。彼女は作家としての目標を達するためにも、あるバランス、ゲーム、そしてシステムを作り出す必要がありました。

彼女は住宅が作品化することへの疑問を呈しつつも、柿生の住宅において、弾丸をひらりとかわし、雨つぶの間をすり抜けるようにして、まさにその方法を見つけ出しているのです。ほとんどポルノ的に住宅を作品化する方法を。それを誇らしげに見せるわけでもなく。

彼女の芸術的な目標とは何だったのでしょうか?

長谷川逸子は、L字の空間のことを寝室、リビングなどとは絶対に呼ばないのです。代わりに「主室1」、「主室2」と呼んでいるのです。このことから多くのことがわかりますね。サービスブロックの部屋には全て、キッチン、風呂、洗面所、寝室などの名前がついていますから。つまり、住宅は特定の用途のためにあるのではない、ということを示唆しているのです。それは、空間に関することなのです。

副次的な部屋というものは、実利的な理由で存在するものですが、結局は何が重要かをフレーミングする効用があるのです。発表された写真に、サービスブロックの中で唯一写っているのは、階段ですね。圧縮された空間を通過させるだけの基本的な装置ですが、ここでは、二階にある二つ目のL字空間へと至るまでに、一階空間での経験をほとんど忘れさせてくれるような効果があるのです。

一階のL字空間は二つに分断されています。一方にはキッチンに面してダイニングテーブルが置かれており、もう一方はいつも空っぽの状態です。どちらも写真でも出版物でも見ることができますね。ここは玄関スペースであり、通行のためのスペースでもあり、これからこの住宅が披露してくれるものに備えるための「ウォッシングルーム」だとも考えられるでしょうか。長谷川逸子は、その一角に固定式の家具をいくつか配置していますね。ここには古典的な三位一体の関係 - 玄関、リビング、ダイニングがあるのです。これらの機能は全て、サービスブロックでの行為と関連しながら合理的な感じがします。

普通の住宅では、リビングが一番大きな空間を占めますよね。しかしこの住宅では、上階の主寝室もリビングとほとんど同じ面積を占めているのです。写真でも図面でも、二階のL字空間にはシングルベッドが二つだけ、部屋の片側に配置されています。残りは空っぽのまま。L字空間のそれぞれの端には机があって、この部屋が寝るためでもあり、仕事するためでもあるということを意味しているかのようですね。他には家具はありません。

下階に対しての破滅的な片割れという感じなのでしょうか。床はとても暗いのですが、代わりに壁は全て真っ白です。扉は白い壁面に完全に溶け込むように白のフラッシュ戸で作られています。どこの窓からやってきたのかわからない自然光が、側面から現れ、それが勾配天井にあたり、曲面に影を落とす、その自然光による人工的な魅力は卓越していて素晴らしいのです。

一階では、住宅の社会的空間としてのプログラムに対する伝統主義的とも呼べるような視点に関して、非常に明快な意図がありました。

一方、二階は通常の寝室としては明らかに広すぎるので、自然と別の部屋へと変わってしまうのです。この不均衡な関係と特異性によって、長谷川逸子は、機能こそがデザインの主なモチベーションなのではなく、別の性質、別の象徴的なものがあることを示しているのです。

「象徴的」という言葉を使われましたが、それは何を指しているのでしょうか?

象徴的性質というのは、合理性と関係があると思うのです。本当に象徴的な空間や要素というものは、なぜそこにあるのか、なぜそうなのか、とあなたに考えさせてくれるのです。

日常的ではなく、分類しづらい、それでいて奇妙な魅力があるもののことです。それは、機能や技術的な説明を超えた解釈や、考えを与えてくれ、議論させてくれるものなのです。

玄関ホール、リビング、寝室、などといった観点から住宅を捉えるような古典的なやり方で、機能を考える方法は、個人的には非常に時代遅れな考え方だと思いますね。私たちは実践において、明確な実利的解答を見いだせないような配列関係を探っているのです。つまり今日、私たちがしているような刺激的な議論のきっかけとなるアンカーを探し出すためにも、曖昧で抽象的な観念を取り入れているのです。

私たちが研究していく中で、日本の事例から学んだことはまさに、現実と非現実の境界を曖昧にすること、つまりは、家に住むという固定観念を取り払い、別の選択肢を与えることの重要性なのです。私たちも、そういった事例の家族の一員となりたいと思っていますし、上手くは定義できないような「もの」を求めているのです。私たちは、それを空間や要素の象徴的、記号的性質と呼んでいるのです。

日本の建築家が、この性質に対して非常に敏感になったのはなぜだと思われますか?

それに関しては推測が可能です。日本語は、私たちが一言で表現してしまうようなことを定義するために、いくつかの記号を使いますよね。例えば、白、背景、などを定義する記号は、いくつもあるのです。ヨーロッパ的な視点からは、何もない白い背景、を理解することは非常に明快なことなのですが、日本では、どのように何もないのか、どういった白なのか、などを明らかにしておきたいのでしょう。同じことが、柱、にも当てはまります。私たちは、コラム、ポスト、ピラーなどいくつかの定義を持っていますが、それらはほとんど同じものを指しています。日本語では、柱、が何を意味するのかはその柱の位置によって様々な定義があるのです。もしそれが構造の中心に位置している場合は、特定の名称を持ちますし、外周部に位置している場合はまた別の名称を持ちます。下級建築とも呼べるような建物にある場合と、寺院のように重要な象徴的建築にある場合とでは、別の意味を持つのです。それぞれの言葉の意味を具体的に考えることは、結果的にそれぞれのモノの意味を具体的に考えることなのですが、それは日本の文化に深く根ざしていることなのです。

しかし、私が最も重要だと思うことは、この時代の建築家たちが、ある結実した成果に到達できたということだけでなく、彼ら自身が自らの作品についての理論化を途方もないほどに試みていたということなのです。これらの建築家たちはみな、いくつかの雑誌に掲載された文章の中で、自身が行っていたことを記述しています。80年代の「新建築」は毎月10万部発行されていました。宮脇檀、坂本一成、そして長谷川逸子らの論考が定期的に一般の人々の手元にも届いていたのです。一般の市民もたまには、こういったテキストを読んでいたのでしょうね。写真だけではなく膨大な情報が流布されていたのです。建築の論考があらゆる人へと届いていたのです。

現代の日本建築のマンネリ化は、そういったことがなくなってしまったことに大きく起因しているのだと思います。伊東豊雄が最後にそのような文章を書いたのも、おそらく30年も前のことでしょう。現代の日本のスターアーキテクト世代は全く異なる方向へと進んでいます。アトリエ・ワンのリサーチについて言及するにも、それはイツコの時代とは全く異なるものですよね。今日では、アトリエ・ワンのような建築家たちは、建築的空間を創造する理論よりも都市のスケールに関心を持っています。

70年代、80年代の日本の建築は、経済的、社会的事象によって生じた、ある現象で、それを支えていたのは狂気的なほどの出版物への情熱なのです。そのおかげで、全世代の建築家たちは足を止め、考え、実験し、解釈し、お互いにコミュニケーションを取り合い、それが結果として大衆へと届くこととなったのです。ミヤワキは美しい文章を書いていて、このような努力は全て世界を変えるためになされたことなのだと結論づけているのです。そこには闘志と使命感があったのです。彼らの敵はいつしかメタボリストではなく、プレファブ住宅へと変わっていきました。印象派の作家たちが写真に対抗したのと同じように、建築家たちもまた、彼らに取って代わろうとするものへ対抗するための活力が必要でした。

私たちの議論しているこの住宅が建てられた時代は、あらゆることが急速に変化した時代だったのです。土地の価格も急激に上昇していきました。いくつかの住宅はたった二、三年しか存続しなかったのですが、それも土地の価格が上昇し続けているために、すぐに買い換えることができたからなのです。建築家たちは、彼らの住宅が長く存続しないことを知っていたのです。そういった事情から、日本のクライアントたちは、より柔軟で、型にはまらない設計を許容できたのです。ヨーロッパでは、私たちは住宅を一生のものとして建ててきました。対して、彼らは10年単位で建ててきたのです。これは大きな違いです。

この現象をマクロで見ると、非常に興味深いものがあります。出版物はまさにゲームチェンジャーであったわけです。現在、日本に存在するプレファブ住宅は、40年前に建築家たちが理論化したデザインに深く影響を受けています。「カサベラ」や「ドムス」もヨーロッパでは、このようなことは、成し得ませんでした。これらの日本の出版物は、日本でのこうした状況に貢献してきたのです。

柿生の住宅に話を戻したいと思います。出版物では伝えきれなかったことがあるとすればそれは何だと思われますか?

この住宅の出版物では表現しきれなかったこと、それはこの住宅の音響的効果の探索

でしょうか。この住宅へと入っていくことを想像します。5人の人がテーブルを囲んで食事をしています。その姿は見えないですが、声は聞こえますね。夕食の時間を想像してみます。側面から自然光が入ってくる事はなく、何かしらの人工照明がテーブル近くにあるのではないでしょうか。そうすると、この白い曲面全体に人の影が映し出されるでしょう。出版物の写真は、人が住み着いたものではなく、演出されていて、これらの空間の劇的な要素が示される事はありません。

これは、アルヴァロ・シザとエドゥアルド・ソウト・デ・モウラとの間で交わされた興味深い議論のポイントでもあるのです。何年も前の事になりますが、ポルトの大学で、彼らは、海の前に建つ住宅の窓は小さい方が良いのか、それとも大きい方が良いのか、という議論をしていたのです。彼らはお互いに反対の意見を持っていました。ソウト・デ・モウラは部屋からは海全体が見えるようにすべきだと考えていたのですが、シザは、そうじゃない、海を見に行こうという気持ちにさせるためにも、窓は小さくするべきだと言ったのです。そっちの方が努力を強いるものですけどね。

この世代の日本人は、人を惹きつけ、刺激し、移動させるような仕掛けを考えていたという点で、シザの方に賛同していたでしょう。この住宅内における、影との戯れや社会的な振る舞いは、私たちが見ることのできる出版物からとは、全く異なる深い効果を持っていたと思います。

柿生の住宅は白の家と呼べるでしょうか、それとも黒の家と呼べるでしょうか?

どちらとも言えないと思います。ここでの白は、ただ付随的なものだと思います。シノハラの第二様式の住宅のようなポレミックな白ではないですよね。抽象的な白でもない。何よりも、目的のための手段なのです。年表で見てみると、柿生の住宅はシノハラの第二様式の終わりと、第三様式の始まりとの間に建てられているのです。この白はただ、そこで起きる何かに寛容な白だと思うのです。「谷川さんの住宅」においての白が、木の形をした柱や傾斜した土間を空間の主役とするようにね。

柿生の住宅においての白、そして床の暗いカーペットは必要なものだと思いますね。そのおかげで、二つの窓や、ダブルハイトの光源からやってくる光の効果が理解できるのです。

日本では、景色の見えない窓はよくあることです。敷地があまりにも狭く、光もほんの少ししか入ってきません。窓に対する固定観念を打破し、単に外をみるための装置以上のものとして窓を捉え直すためには、何が論点になると思われますか?

日本の都市のカオス、そして建築と都市の関係についてはメタボリストから藤本壮介に至るまで様々な建築家たちによって多くの理論が書かれていますね。これらの世代はいずれも、非常に密集したメタボリックな都市の状況を扱っていますし、そのほとんどにおいて採光と換気の必要性から窓をデザインしているのです。その窓から何が見えるのか、ということではなく、です。

窓は、ある住宅とある場所を結びつける数少ない要素の一つですが、この世代の建築家たちはそれを望んではいなかったのです。

柿生の住宅の窓の写真においては、窓は燃えてしまったように - つまり窓の外はただ白くなっているだけなのです。これは、シノハラが理論化した住宅の自律性に対しての別の表現なのです。住宅には敷地がなく、コンテクストにも属さず、どこにでも存在し得る、という自律性です。もし窓から景色が見えないのであれば、その意図については語らざるを得ないでしょう。

柿生の住宅では、曲面の壁に穿たれた窓が、一階の主室に自然光をもたらしている外壁の窓と向かい合っているわけですが、長谷川逸子は、その角度によって、両方の窓から同時に外を見通すようなことができるかどうかなど気にしていなかったのだと思います。それが主題では全くないですからね。

窓は全て正方形で、完璧にフレーミングされています。この住宅と、それを取り囲むコンテクストを繋ぎ止める事実上のアンカーとしてではなく、むしろ壁に描かれた絵画のようなものなのです。

この住宅を別の用途として使う事は想定できますか?この住宅を自分のものにしたいと夢見るような事はありますか?

主室にベッドを置くことはまずないでしょうね。サービス部分に配置すると思います。上階は仕事をする空間、そして下階は人との関わりを持つような空間とするでしょうか。例えばですが。二つの主室は、夏の部屋と冬の部屋、あるいは読書する空間と、仕事をしたり音楽を聴く空間でもいいでしょう。L字の空間はただ寝るだけの部屋としては強すぎると思うのです。そこは、別の次元、象徴的な次元へと外挿されるような性質や特徴を持っているのです。まったく空っぽなその空間をたまに通り過ぎていく、そのような事はイメージできますけどね。シノハラの第二様式における亀裂の空間的な質があると思います。そこは椅子をおいておけばそれで十分な空間ですよね。

私にとって、この住宅の最大の挑発的主張は、写真や図面に示された二つのマットレスなのです。二つのベッドをそこに置くことで、長谷川逸子は「サービスの提供者と芸術家との間のジレンマ」を貫いているのだと思います。これが私のせざるを得なかった事であり、やりたいことのために、ここまでやってきたのだ、と彼女は言っているのです。

柿生の住宅に対して、不思議に思うところはありますか?

柿生の住宅が建てられたころ、シノハラは上原通りの住宅や谷川さんの住宅を手がけていました。彼は構造や象徴的な構造物と戯れていたのです。長谷川逸子も空間を作るために構造を利用した住宅を作っていました。例えば、焼津の住宅2がありますね - それは構造が住宅であり、またその逆でもあるのです。ところが柿生の住宅においては、構造が非常にうまく隠蔽されています。梁や柱がどこにあるのかわからないでしょう。ある瞬間を除いては。それは屋根裏から撮られた一枚の写真にあるのです - 全ての面材の収束点に柱があり、その柱は屋根に触れているのです。他の階からは、その姿が見えることはありません。言及もされていませんし、そのことを示すものも何もありません。長谷川逸子は、その具体的な写真を一枚、海外の出版物に掲載したのです。柱の姿が現れる、ほとんど知覚不可能な瞬間を、彼女は何らかの理由で外部に公開しようと決断したのです。構造の配置計画や表現が価値を持ち得た時代に、彼女は、住宅の中で、最も重要度が低く、最もアクセスしづらい空間にだけ、その柱の姿を暴露させていたわけです。そのことが、私に問いかけてくるのです。彼女はそのとき一体何を考えていたのだろうか、と。

2021年9月18日

Filipe Magalhães: The limbo in which we, fala, operate - between the lack of interest of the client and the excess of ambition and enthusiasm on our side - is very similar to the situation Itsuko Hasegawa was confronted with, while designing her first houses in the 70s.

YOU PUBLISHED THE DRAWINGS AND PHOTOS OF THE HOUSE IN KAKIO IN YOUR RECENT BOOK ON JAPANESE HOUSES. FROM ALL THE BUILDINGS YOU ANALYSED, WHAT MADE YOU MAKE THIS CHOICE?

It is a house built with very little resources. It’s a banal construction of a boring brief. It’s a discrete, cheap, suburban house. However, the discrepancy between what we could call a very unappealing exterior and a phenomenal interior composition - not in a tectonic sense, but in a spatial and symbolic sense, is surprising. It is almost as if Itsuko designed a house that disappears from the outside on purpose, in order to protect the treasure that hides within.

It has two and a half levels - a social level, a so-called private level, and an attic level. The social level has some program in one corner and a big L - shaped living room in the other corner. The same structure applies to the private level, with some bedrooms in the first corner and a big master bedroom in the second corner.

My reading, however, tells me that the conventional understanding of this house - a social part, a private part, a bedroom, a living room, a space for family members, a space for guests - all these words that we usually use to define the daily life of a house, turn out to be completely irrelevant and insufficient to grasp the real quality present.

If you take all the furniture away from the plans, you end up with a house based on two games - a game between the main and the secondary spaces on each level, and a game between the outside rectangular shape and the inside curved shape, which create important differences and interdependence in the L-shaped rooms on each level. You discover a play of angles, surfaces and light that make sense, independent of any use. It is remarkable that there are no material or structural special effects: there are just walls, windows, ceilings, and floors. Everything is out of white painted plywood. In this sense, it is the work of a master, whereby she truly understood the tools and limitations present and used them only to her advantage. All this is just fantastic.

IN THE TEXT ITSUKO HASEGAWA WROTE ABOUT THE HOUSES SHE BUILT IN THE 70’ („MY WORK OF THE SEVENTIES” IN SD 04/85) SHE SURPRISINGLY UNDERLINES HER INTEREST IN „THE CONCERNS OF LIVING RATHER THAN ABSTRACT METHODS OF ARTISTIC EXPRESSION”. THE HOUSE IN KAKIO, AS YOU STARTED TO EXPLAIN, IS DEFINITELY NOT ONLY ABOUT THE „CONCERNS OF LIVING”.

This entire generation wrote a lot about the mundane conditions in which they had to operate. Although they were strongly influenced by the ideas of Shinohara, they had to work in the shadow of the Metabolist movement and the emerging prefab house industry. Both praised standardised, repetitive dwellings, produced in huge quantities. The group Itsuko Hasegawa belonged to, were the grunge kids, the ones that had only tiny houses to deal with. They struggled a lot for what they believed was right and with the dilemma: „should we even try to be artists or should we be service providers” was very present in all of them.

Their ambitions, sensibilities and intellectual preparation were inspired by Shinohara’s „house as a work of art”, but their clients were very often not at all interested in architecture, had limited budgets, and tight schedules.

Itsuko Hasegawa worked for Shinohara at the university and knew his clients, who usually came from the higher layers of the society. She was living in both worlds - the elite, and the ordinary reality of a young architect in Japan. She was very conscious of the schizophrenic situation many of her colleagues had to find an answer to. To remain in practice, they were forced to rethink the strategies learned from Shinohara, as his school and methods turned out to be impossible to apply in the majority of cases.

Everything that came to happen in Itsuko Hasegawa’s career was triggered by this contradiction. What she quickly accepted was that maybe her vocabulary, her language, could not be as pure as Shinohara’s. Maybe she could not be as aggressive as he was. She had to create a certain balance, invent games and systems in order to achieve her goals as an author.

Even though she wrote about her doubts on the possibility of a house being a work of art, in Kakio she dodged the bullets, walked between the drops of rain, and found a way to do exactly that, almost pornographically making a house a work of art - without even boasting about it.

WHAT WAS HER ARTISTIC GOAL?

Itsuko Hasegawa never calls the L-shaped spaces bedroom and living room. Instead, she calls them „main room one” and „main room two.” This tells us a lot, because the rooms in the service block, all have names like kitchen, bathroom, washroom, or bedroom. L-rooms remain „main rooms”. It suggests that a house is not about specific uses. It is about space.

Secondary rooms are there for pragmatic reasons and eventually help to frame what is important. The only published picture of the service block is the staircase - a fundamental device to force you to go through a compressed space, and makes you almost forget the experience you had at ground floor before accessing the second L-shaped space on the first floor.

The ground floor L-shape room is divided in two. There’s a side with a dining table, facing the kitchen and the other which is always empty, both in photos and publications. You assume it to be the entrance space, a space to pass through, a kind of „washing room” where you get ready for what the house is going to reveal to you. In the corner, Itsuko Hasegawa designed a few pieces of fixed furniture. We have a classic triad - entrance, living, dining. All these functions are related to what happens in the service block and have a reasonable surface.

In a normal house, the living room is the biggest space. In this house, the upstairs master bedroom is almost the same area. Both in photos and drawings, the first floor L-shaped space is furnished with only two single beds, orientated on one side of the room. The rest of the room is just empty. At the end of each side of the L-shape, there is a desk, as if this space was meant for both sleeping and working. There is no other furniture. It is a kind of subversive twin of the room below. The floor is very dark, but all the walls are white. The doors have flush white frames ready to fully melt into the white wall surface. The plastic appeal of the natural light, that comes from windows not immediately visible, appears from the side, and hits the pitched ceiling, casting a shadow on the curve, is outstanding.

At ground floor, she had a very clear intention regarding what we can call a traditionalist perspective on program in the social space of a house.

Upstairs instead, there is clearly too much area for a standard bedroom, so the room automatically becomes something else. Thanks to this disproportion and peculiarity Itsuko Hasegawa demonstrates that function it is not the main motivation in her design, but something of another nature, something symbolic.

YOU USE THE WORD „SYMBOLIC” IN REGARD TO SPACE. WHAT DO YOU REFER TO?

I think the symbolic aspect has to do with rationality. A truly symbolic space or element puts you in a position to wonder why it is there, and why like this? It has an appeal of something out of ordinary, not easy to classify, a bit strange. It makes you interpret, think and discuss beyond the functional or technical descriptions.

As far as I am concerned, the way of thinking about functions in the classical sense, in which we think of a house in terms of an entrance hall, a living room, a bedroom, etc. is a very outdated perspective. In our practice we are looking for arrangements in which it is impossible to discern clear pragmatic answers. We introduce vague, abstract notions in order to find an anchor that will trigger some sort of inspired discussion - like the one we are having today.

What the Japanese references showed us during our research, was exactly the importance of blurring the boundaries between the real and the unreal in the sense of giving an alternative, deconstructing the stereotypes about how to live in a house. We want to be part of this family and look for the „thing” that we don’t know how to define very well. We call it a symbolic, or semiotic quality of space and elements.

WHAT DO YOU THINK PUSHED JAPANESE ARCHITECTS TO BECOME EXTRAORDINARILY SENSITIVE TO THIS QUALITY?

We can speculate on that. Japanese language has several symbols to define what we describe with one word. They have several symbols to define white, background etc. Understanding an empty white background from an European perspective is pretty clear, in Japan they would want to clarify how empty, which white, etc. The same thing applies to a column. We have words like column, post, pillar - a few definitions that pretty much refer to the same thing. The Japanese have numerous definitions for what a column means, depending on its position. If it’s in the centre of a structure, it has a specific name, if it’s on the perimeter, it has another If it is in what we could call a low-class building, it has a certain sense, if it is an important symbolic building, like a temple, it has another. It is deeply rooted in Japanese culture to be specific about the meaning of each word and as a consequence of each object.

However, what I believe to be the most important factor is that in this period architects not only intimately arrived at certain conclusions, but also theorised tremendously about their own work. All of these architects wrote and depicted what they were doing in texts published in several magazines. Shinkenchiku in the 80’ had a circulation of one hundred thousand prints every month. The general population was receiving theory from Mayumi Miyawaki, Kazunari Sakamoto and Itsuko Hasegawa among others at regular intervals. An ordinary citizen would probably read one of these texts once in a while. There was a huge diffusion of information that was not just photographic. Architectural theory was reaching everyone.

To a large extent, I think, the cliche of contemporary Japanese architecture, comes from the fact that this does not happen anymore. Last time Toyo Ito wrote a relevant text was probably 30 years ago. The current generation of star architects in Japan have moved in a very different direction. Even if you mention the research of Atelier Bow Wow, it is very different from what happened in Itsuko’s times. Nowadays, architects like Bow Wow are more interested in the urban scale than in the theory of architectural space making.

Japanese Architecture in the 70’s and 80’s was a moment created by economic and social issues which were then supported by an insanely intense publication frenzy, that in turn allowed a whole generation of architects to stop, think, experiment, read, communicate with each other and consequently, reach the masses. Miyawaki wrote a beautiful text, concluding, that all this effort was aimed at changing the world. There was a combat spirit and a mission. Their enemies at some point stopped being the Metabolists and started to be prefab houses. Similarly, to the impressionists who had to fight photography, architects had to find the energy to fight back, as something was trying to replace them.

The period in which the house we are discussing was built was a period when everything was happening very fast. The price of land was increasing drastically. Some of these houses lasted just a couple of years because the ever-increasing price of land meant they could be replaced right away. The architects knew that their houses were not meant to last. All this allowed Japanese clients to be a bit more flexible and allow more unconventional layouts. In Europe we built for a lifetime. They built for a decade. This makes a huge difference.

It’s very interesting to look at this phenomenon at a macro scale. The publications were really a game changer. Today, the prefab housing that still exists in Japan is deeply influenced by the design these architects theorised 40 years ago. Neither Casabella nor Domus managed to do that in Europe. All of these Japanese publications were contributing to this in Japan.

COMING BACK TO THE HOUSE IN KAKIO, WHAT DO YOU THINK WAS NOT POSSIBLE TO TRANSMIT IN PRESS?

There’s something that the publications of the house never managed to do, which was to explore the acoustic aspect of the house. If you imagine that you just entered, and there are five people having a dinner where the table is drawn, you don’t see them, but you hear them. And if you assume it’s a dinner time, you probably don’t have the natural light coming from the sides, you have some sort of artificial light near the table. You’re going to see the shadows of these people spread all over this white curved surface. In the publications the photos are never inhabited, they are staged and do not show the dynamic components of these spaces.

This is also an interesting point of discussion between Alvaro Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura. Many years ago, at the school in Porto, they were debating if a house in front of the sea, should have a small window or a big window. They disagreed. Souto de Moura felt you should see the whole sea from the room. Siza instead said, no, you should make it small so that people are motivated to go to see the sea. It needs to become something you have to make an effort for.

I would say this Japanese generation agreed with Siza, thinking in terms of hints that attract and provoke you to make you move. I think the play of shadows and the social behaviour inside this house would have a profound effect, very different from what we see published.

WOULD YOU CALL THE HOUSE IN KAKIO A WHITE HOUSE OR A BLACK HOUSE?

I wouldn’t call it either. I think the white here is just circumstantial. It’s not a polemic white like the second style houses of Shinohara. It’s not an abstract white. More than anything else, it’s a means to an end. If you look at it in a timeline, the house in Kakio is built between the end of the second style of Shinohara and the beginning of the third style. I think this white is a white that just liberates something to happen, like in Tanikawa house, where the white makes the tree shaped columns and the sloped earth floor the protagonists of the space.

I think the white in Kakio and the dark carpet on the floor are necessary, so that you understand the light effects coming from two windows and the double height light source on the ground floor.

IN JAPAN, OFTEN YOU HAVE A WINDOW THAT DOESN’T HAVE A VIEW, IT GIVES ONLY A LITTLE BIT OF LIGHT BECAUSE THE LOTS ARE SO TIGHT. WHAT DO YOU THINK MIGHT BE AN ARGUMENT TO DESTROY THE COMMON STEREOTYPE OF A WINDOW AND CONCEIVE IT AS SOMETHING OTHER THAN A DEVICE TO PURELY LOOK OUT OF?

There’s a lot of theory about urban chaos of Japan and the relationship between architecture and the city written by different architects from the Metabolists to Sou Fujimoto. All of these generations were dealing with the very dense, metabolic urban condition and most often they designed windows just because the building needed to have them for light and ventilation, not because of whatever the window was going to reveal.

A window is one of the few elements that links a specific house to its specific place. The architects of this generation didn’t want it.

The photos of the windows in the house in Kakio, show them burned - the outside becomes just white. It’s another way of speaking about the autonomy of a house theorised by Shinohara - the house has no site, it does not belong to the context, it can be anywhere. If a window doesn’t give you a view it certainly helps to speak about this intention.

In house in Kakio the windows cut in the curved wall are facing the window in the outside wall, that gives some natural light to the main room in the groundfloor. However, I don’t think that Itsuko Hasegawa cared if the angle allowed a person to see through both windows at the same time. That’s not the topic at all.

All of the windows are squares, perfectly framed. They are more like paintings on the wall rather than actual anchors to the context that surrounds the house.

IS THERE ANY WAY IN WHICH YOU WOULD USE THIS HOUSE DIFFERENTLY? DO YOU HAVE SOME KIND OF DREAM OF HOW YOU WOULD MAKE THIS HOUSE YOUR OWN?

I wouldn’t put my bed in any of the main spaces. I would probably place it in the service part, and I could imagine the top level to be the space where I work, and the bottom level the space where I relate with other people, for example. Two main rooms could be for instance a room for the summertime and the room for the winter or a space to read and a space to work or to listen to music. I think the L-shaped rooms are too intense to just sleep in them. I think they have qualities and characteristics that extrapolate them to another level, a symbolic one. I could imagine them to be completely empty and just to walk through them once in a while. They have the fissure space quality of Shinohara’s second style houses, where you put a chair and it’s enough.

To me, the biggest provocations in this house are those two mattresses in the photos and plans. By putting the two beds there, I think, Itsuko Hasegawa is poking the „service provider versus artist” dilemma. She’s saying - “this is what I had to do: look how far I went to achieve what I wanted”.

IS THERE SOMETHING THAT REMAINS FOR YOU A MISTERY IN THE HOUSE IN KAKIO?

At the time when house in Kakio was built, Shinohara was working on Uehara House and Tanikawa House. He played with structure, symbolic structure. Itsuko Hasegawa also made houses that used structure to create spaces, for example, the house in Yaizu 2 - the structure is the house and vice versa. However, House in Kakio is one where the structure is pretty much disguised. You don’t know where the beams or columns are, except for one very specific moment, you can only see in one photo from the attic space - there is a column that appears and touches the roof in the point of convergence of all the surfaces. It doesn’t show up in the other levels. There’s no writing, nothing that refers to it. Itsuko Hasegawa published one specific photo of it in an international publication. She decided for some reason to reveal to the outside world that almost unperceiveble moment where the column appears. In the time when the positioning of structure and the expression of structure was so relevant, she reveals it only in the least important, and most difficult to access space. It leaves me wondering, what was she thinking about.

18.09.2021

菲利普・麦哲伦:我们Fala工作室这种,在甲方兴趣的缺乏,和我们雄心和热情的过度中运作的处境,和长谷川逸子在70年代设计她的第一批住宅时遇到的情况非常相似。

你在最近出版的《日本住宅》一书中发表了柿生的住宅的图纸和照片。在你分析的所有建筑中,是什么让你做出了这个选择?

这是一个用极少的资源建造的住宅。它是一个无聊指示下的平庸构筑物,一个离散的、廉价的、郊区的住宅。然而,在相当不讨喜的外观和惊人的内部构成之间形成的差异——不是在建构意义上,而是在空间和象征意义上——是令人惊讶的。这几乎就像长谷川逸子故意设计了一个消失于外界的住宅,以保护隐藏在内的珍宝。

它有两层半——一个社交层,一个所谓的私人层,以及一个阁楼层。社交层的一角有一些功能,另一角有一个L型的大起居室。同样的结构适用于私人层,第一个角落有一些卧室,第二个角落有一个大的主卧。

然而,我从中读到的是,对这所住宅的传统理解——社交部分、私人部分、卧室、起居室、家庭成员的空间、客人的空间——所有这些我们通常用来定义住宅日常生活的词,结果是毫不相关且不足以去把握这个住宅真正呈现出来的品质。

如果从平面图上拿掉所有家具,你会得到一所基于两个游戏的住宅——每一层的主要空间和次要空间之间的游戏,以及外部矩形和内部曲线之间的游戏,这在每一层的L形房间中创造了重要的差异和依存。你会发现角度、表面和光线的把玩是有意义的,与任何用途无关。值得注意的是,这里没有任何材料或结构上的特殊效果:只有墙壁、窗户、天花和地板。所有东西都是用刷白的胶合板制成的。在这个意义上,它是一个大师的作品,在此她真正理解目前的工具和限制,并只使用它们来发挥她的优势。所有这一切都很精彩。

在长谷川逸子写的关于她在七十年代建造的住宅的文章中(“我的七十年代作品”,载于SD 04/85),她令人惊讶地强调了她对 “生活的关注而不是抽象的艺术表达方法 “的兴趣。柿生的住宅,在你开始的解释中,绝对不仅仅是在于 “生活的关注”。

这整整一代人写了很多文章关于世俗的状况,他们必须运作于其中。尽管他们受到筱原思想的强烈影响,但他们不得不在新陈代谢运动和新兴的预制房屋行业的阴影下工作。两者都推崇标准化的、重复性的住宅,并大量生产。长谷川逸子所属的群体是颓废派(grunge)的小孩,那些只有小房子可以处理的人。他们为自己认为正确的事情做了很多挣扎,并陷入两难境地:”我们应该甚至尝试成为艺术家,还是应该成为服务提供者”,这在他们所有人身上都很常见。

他们的雄心壮志、情感和智识准备都受到筱原 “作为艺术作品的住宅 “的启发,但他们的客户往往对建筑一点都不感兴趣,预算有限,时间紧迫。

长谷川逸子在大学里为筱原工作,认识他的客户,他们通常来自于上流社会。她生活在两个世界里——精英阶层,以及日本年轻建筑师的普通现实。她非常清楚她的许多同侪必须找到对这种精神分裂的状况的答案。为了保持实践,他们不得不重新思考从筱原那里学到的策略,因为他的学派和方法在大多数情况下都无法适用。

长谷川逸子职业生涯中发生的一切,都是由这个矛盾引发的。她很快接受的是,也许她的词汇,她的语言,不可能像筱原那样纯粹。也许她不能像他那样积极进取。她必须建立某种平衡,创造游戏和系统,以实现她作为一个作家的目标。

尽管她在书中写道,她对房子成为艺术品的可能性表示怀疑,但在柿生的住宅中,她躲过了子弹,在雨滴间行走,并找到了一种方法,几乎像情色画般地将房子变成了艺术品——甚至没有对此夸夸其谈。

她的艺术目标是什么?

长谷川逸子从未将L型空间称为卧室和起居室。相反,她称它们为 “主房间一 “和 “主房间二”。这告诉我们很多,因为服务区的房间,都有厨房、浴室、盥洗室或卧室这类名称。L型房间仍然是 “主要房间”。这表明,住宅不是关于具体的用途。它是关于空间的。

次要房间的存在是出于实用的原因,并最终帮助框定重要的东西。服务区唯一公布的照片是楼梯——一个迫使你穿过压缩空间的基本设施,并使你几乎忘记了在进入二楼第二个L形空间之前在一楼的经历。

一楼的L型房间被一分为二。一边是餐桌,面向厨房,另一边在照片和出版物中都是空的。你假设它是入口空间,一个通过的空间,一种 “洗涤室”,在那里你为住宅将要呈现给你的东西做好准备。在角落里,长谷川逸子设计了几件固定的家具。我们有一个经典的三要素——入口、起居、餐厅。所有这些功能都与在服务体块内发生的事情有关,并且有一个合理的完成面。

在普通的住宅里,起居室是最大的空间。而在这所住宅中,楼上的主卧室几乎是相同的面积。在照片和图纸中,二楼的L形空间只布置了两张单人床,放在房间的一侧。房间的其余部分都是空的。在L型的每一侧的尽头,都有一张书桌,似乎这个空间既是用来睡觉的,也是用来工作的。没有其他家具。它是下面房间的一种颠覆性的孪生。地板很暗,但所有的墙壁都是白色的。门有着齐平的白色门框,妥帖的融化在白色的墙面上。可塑性很强的自然光,源自无法立即可见的窗户,从侧面显现,打在倾斜的天花板上,在曲面上落下投影,非常卓越。

在一楼,她有一个非常明确的意图,从所谓传统主义的视野出发,对住宅的社交空间进行编排。

而在楼上,对于一个标准的卧室来说,显然面积太大,所以房间自动成为了其他什么。得益于这种不相称和特殊性,长谷川逸子表明,功能不是她设计的主要动机,而是一些其他性质的东西,象征性的事物。

你在谈到空间时使用了 "象征性 "一词。你指的是什么?

我认为象征性的层面与合理性有关。一个真正的象征性的空间或元素让你想知道它为什么在那里,为什么是这样的?它有一种超乎寻常的吸引力,不容易分类,有点奇怪。它使你在功能或技术描述之外进行解释、思考和讨论。

就我而言,古典意义上从功能来思考的方式,即我们从入口大厅、起居室、卧室等方面来思考一所住宅,是一种非常过时的观点。在实践中,我们在寻找布局,其中不可能辨别出明确的实用性答案。我们引入模糊的、抽象的概念,以便找到一个锚,引发某种启发式的讨论——就像我们今天这样。

在我们的研究中,日本的案例向我们展示的,正是模糊真实和非真实之间界限的重要性,在这个意义上给出选择,解构了关于如何生活在一个住宅里的刻板观念。我们想成为这个家族的一部分,寻找我们不知道如何准确定义的“东西”。我们称之为空间和元素的象征性的,或符号学的品质。

你认为是什么推动了日本建筑师对这种品质变得异常敏感?

我们可以对此进行推测。日语有好几个字符来定义我们用一个词描述的东西。他们有一些字符来定义白色、背景等。从欧洲的角度理解一个空的白色背景是很清楚的,在日本,他们会想澄清如何空,哪种白色等等。同样的事情也适用于柱子,我们有像column,post,pillar这样的词——几个释义几乎指的是同一件事。日本人对柱子意味着什么有许多界定,这取决于它的位置。如果它在一个结构的中心,它有一个特定的名称,如果它在周边,它有另一个。如果它在所谓低级别的建筑中,它有某种定义,如果它是一个重要的象征性建筑,如寺庙,它有另一个。对每个词的意义以及作为每个物体的结果,它在日本文化中是根深蒂固的。

然而,我认为最重要的因素是,在这个时期,建筑师们不仅密切地得出了某些结论,而且还对自己的成果进行了巨大的理论化工作。所有这些建筑师都在一些杂志上发表文章,描述他们正在做的事情。80年代的《新建筑》每月有十万份的发行量。普通民众定期收到宮胁檀、坂本一成和长谷川逸子等人的理论。一个普通公民可能偶尔会读到其中的一篇文章。这有着一个巨大的信息扩散,不仅仅是影像的问题。建筑理论在当时普及到了每个人。

在很大程度上,我认为,当代日本建筑的陈词滥调,源自于于这种情况不再发生了。上一次伊东丰雄写相关的文章可能是在30年前了。日本这一代的明星建筑师已经朝着一个非常不同的方向发展。即使你提到犬吠工作所(Atelier Bow Wow)的研究,也与逸子时代的情况大不相同。现在,像犬吠工作室这样的建筑师对城市尺度更感兴趣,而不是建筑空间制作的理论。

70年代和80年代的日本建筑处于一个由经济和社会议题创造的时刻,然后由疯狂的出版狂潮支持,这反过来又让整整一代的建筑师停下来,思考,实验,阅读,相互交流,从而抵达大众。宫胁写了一篇漂亮的文章,结论是,所有这些努力都是为了改变世界。有一种战斗精神和使命感。他们的敌人在某种程度上不再是新陈代谢主义,而开始是预制住宅。类似于印象派必须与摄影作斗争,建筑师必须找到能量来反击,因为有些东西正试图取代他们。

我们讨论的这所住宅的建造时期是一个一切都发生得非常快的时期。土地的价格在急剧上升。有些住宅只留存了几年,因为不断上涨的土地价格意味着它们可以马上被取代。建筑师们知道,他们的住宅并不意在持久。所有这些使得日本业主可以更灵活一些,允许更多非常规的布局。在欧洲,我们的建筑为一生而建。他们是以十年为单位而建的。这就有了巨大的区别。

从宏观上看这种现象是非常有趣的。这些出版物确实改变了游戏规则。今天,在日本仍然存在的预制房屋设计深受这些建筑师40年前的理论的影响。在欧洲,Casabella和Domus都没能做到这一点。所有这些日本出版物都对日本的这一切做出了贡献。

回到柿生的住宅,你认为有什么是无法在媒体上传播的?

有一件事是住宅的出版物无法做到的,那就是探索住宅的声学层面。如果你想象你一进入,有五个人正在描绘餐桌的位置吃饭,你看不到,但能听到他们。而你假设这是晚餐时间,可能没有自然光从侧面射来,你在桌子附近有某种人造光。你会看到这些人的影子遍布在这个白色的弧形曲面上。在出版物中,这些照片里从来没有人居住,它们是布景式的,没有显示出这些空间的动态成分。

这也是阿尔瓦罗-西扎和艾德瓦尔多客苏托客德客莫拉讨论的一个有趣的点。许多年前,在波尔图的学校里,他们争论于,在海边的住宅应该有一个小窗户还是一个大窗户。他们意见不一。苏托-德-莫拉认为你应该从房间里看到整个大海。西扎却说,不,你应该把它弄小,这样人们才会有动力去看海。它需要成为你必须努力去做的事情。

我想说的是,这一代日本人同意西扎的观点,考虑用暗示来吸引和激发你,使你行动。我认为这所住宅中对影子和社会行为的把玩会产生强烈的效果,与我们在出版物中看到的非常不同。

你会将柿生的住宅称为是白住宅还是黑住宅?

两个我都不会说。我认为这里的白色只是间接的。它不像筱原第二样式住宅那样的论战性(polemic)的白色,这不是一种抽象的白色。更重要的是,它是达到目的的一种手段。如果你从时间轴上看,柿生的住宅是建造于筱原第二样式结束和第三样式开始之间。我认为这种白色解放了一些事物的发生,就像在谷川之家里,白色使树形的柱子和倾斜的夯土地面成为空间的主角。

我认为柿生的住宅的白色和地面上的深色地毯是必要的,这样你就能理解一楼中来自两个窗户和通高的光源的光线效果。

在日本,通常你有一个没有风景的窗户,它只提供一点点的光线,因为地块非常狭窄。你认为有什么理由能打破窗户的常规刻板观念,把它构想为一个单纯看室外的设施以外的东西?

有很多关于日本城市乱象的理论,以及从新陈代谢派到藤本壮介的一系列不同建筑师写的建筑与城市的关系。所有这几代人都在处理非常密集的、新陈代谢着的城市状况,大多数情况下,他们设计窗户只是因为建筑需要有窗户来采光和通风,而不是因为窗户会揭示出什么。

窗户是为数不多的将特定房屋与特定地点联系起来的元素之一。这一代的建筑师们并不希望如此。

柿生的住宅中窗户的照片显示它们被销毁了——外面变得只是白色。这是谈论筱原理论中住宅的自主性的另一种方式——这个住宅没有基地,它不属于文脉(context)中,它可以在任何地方。如果一个窗户不给你视野,这当然有助于谈论这个意图。

在柿生的住宅里,在弧形墙上开的窗户正对着外墙的窗户,这给底层的主要房间带来了一些自然光。然而,我认为长谷川逸子并不关心这个角度是否能让人同时看到两个窗户,这完全不是议题。

所有的窗户都是方形的,有完美的窗框。它们更像是墙上的画,而不是实际连接周边文脉的锚点。

你会有什么不同的方式使用这所住宅吗?你是否有某种使这所住宅成为自己的住宅的梦想?

我不会把我的床放在任何一个主要空间里。我可能会把它放在服务部分,我可以想象顶层是我工作的空间,而底层是我与其他人相处的空间,比如说。两个主要的房间可以是例如夏天的房间和冬天的房间,或者一个阅读的空间和一个工作的空间或听音乐的空间。我认为L型房间太有张力了,不能只在里面睡觉。我认为它们拥有的品质和特点,将其推到另一个层次,一个象征性的层次。我可以想象它们是完全空的,我只是偶尔走过。它们有筱原的第二样式住宅中龟裂空间(fissure space)的品质,在那里你放一把椅子就够了。

对我来说,这所住宅里最大的挑战是照片和图纸上的那两张床垫。通过把这两张床放在那里,我认为长谷川逸子是在挑衅 "服务提供者vs艺术家 "的困境。她在说——"这是我必须做的:看看我为了实现我想要的东西走了多远"。

在柿生的住宅中有什么东西对你来说仍然是个谜吗?

在柿生的住宅被建造的时候,筱原正在建造上原通住宅和谷川之家。他把玩的是结构,象征性的结构。长谷川逸子也做了一些用结构来创造空间的房子,例如,焼津的住宅2——结构就是住宅,反之亦然。然而,柿生的住宅是一个结构被隐藏得很好的作品。你不知道梁或柱子在哪里,除了一个非常特殊的瞬间,你只能从阁楼里的一张照片中看到——在所有表面的交汇点,有一根柱子出现并接触到屋顶。它没有出现在其他表面。没有任何文字,或其他东西提到它。长谷川逸子在一份国际出版物上发表了它的一张具体照片。出于某种原因,她决定向外界展示这个柱子出现的几乎难以察觉的时刻。在结构的定位和结构的表达如此相关的时代,她只在最不重要的、最难进入的空间揭示了它。这让我好奇,她到底在想什么。

2021年9月18日

フィリップ・マガリャインシュ: 私たちファラの活動は、辺獄にあるのです - つまりクライアントの無関心と私たちサイドの過剰な野心や熱意との狭間 - ということですが。それは長谷川逸子が70年代に初めて住宅を設計した時の状況と非常に良く似ているでしょう。

あなたの最近出版された日本の住宅に関する本には、柿生の住宅の図面と写真が載っていますよね。そこで分析された住宅の中から、柿生の住宅を今回選ばれた理由は何なのでしょうか?

この住宅は、非常に経済的に作られています。ありきたりな要望による平凡な建設物。中心地から離れた郊外の安価な住宅。ところが、至極平凡とも言えるような外観とフェノメナルな内部構成との不一致 - テクトニックな意味ではなく、空間的そして象徴的な意味でのですが - は驚きですね。イツコは、この住宅の内部に隠された秘宝を守るために、外からの存在感をわざと消すように設計しているように思えるのです。

この住宅には二つと半分の階層がありますね - ソーシャルな階、いわゆるプライベートな階、そして屋根裏階のことです。ソーシャルな階には、片側のコーナーにいくつかの機能、もう一つのコーナーには大きなL字の形をしたリビング空間が配置されています。同じ構成がプライベートな階でも適応されていて、一つ目のコーナーにはいくつかの寝室、そしてもう一つのコーナーには大きな主寝室が配置されています。

ところが、私の解読においては、この住宅の通俗的理解 - つまりソーシャルな空間、プライベートな空間、寝室、リビング、家族のための空間、そして客のための空間など - これら私たちが日常生活を定義するために使用するあらゆる言葉が、この住宅の本当の質を理解するためには全く無関係なもので、不十分なことだとわかるでしょう。

全ての家具を図面から取り去ってしまいましょう。すると、この住宅が二つのゲームに基づくものだと理解できるでしょう。各階における主と従の空間のゲーム。外部の直角性と内部の曲面性のゲーム。これらが、各階のL字の部屋に大きな差異と相互の依存作用を作り出しているのです。部屋の角、表面、そして光の戯れが用途に関係なく、意味をなしていることに気づくでしょう。材料や構造が特別なものでないことは驚くべきことです。つまりそこには、壁、窓、天井、そして床だけしかないのです。それに全てが白塗装の合板でできています。その意味では、これは巨匠による仕事ですよ。使える道具とその制約を理解しながら本当に上手く利用しています。とにかく素晴らしい。

長谷川逸子は70年代に手がけた住宅についてのテキスト(「70年代の仕事」SD1985年4月号)の中で、意外なことに「芸術的表現のための抽象的手法よりも、むしろ生活への関心」を強調していますね。柿生の住宅は、あなたが説明されたように、生活への関心だけで作られていないことは明らかだと思われるのですが。

この世代の建築家たちは、自身の活動せざるを得ない平凡な状況に対して、多くの文章を書いています。彼らはシノハラの思想に影響を強く受けながらも、メタボリズム運動の影の中、そしてプレファブ住宅産業が台頭する中で活動を強いられたのです。どちらも規格化され、反復可能で大量生産される住宅を称賛していました。それに対して、長谷川逸子の属していたグループはみな、小さな住宅のみを扱うグランジ・キッズたちだったのです。彼らは正しいと信じているもの、そして「芸術家たるべきか、それともサービスの支給者たるべきか」というジレンマとに、格闘していたのです。これらは彼らにみな共通していたことです。

彼らの野心、感性、そして知性の蓄積。それらはシノハラの「芸術としての住宅」に触発されたものでした。ところが、ほとんどのクライアントは建築には全く興味がなく、予算も工期も限られていたのです。

長谷川逸子は、大学でシノハラのもとで働いていましたし、彼のクライアントのことを良く知っていました。彼らはたいてい社会の上流階級の人々でした。つまり彼女は二つの世界を生きていたわけです。エリート層の世界、そして日本の若い建築家が面する、ごく普通の世界。彼女は、仲間たちの多くが応えざるを得ない、このスキゾフレニックな状況を強く意識していました。実務を続けるためには、シノハラから学んだ戦略を見直さざるを得なかったのです。シノハラスクール、そしてその手法は多くの事例においては適応できないことがわかっていたからです。

長谷川逸子のキャリアは、全てこの矛盾した状況が引き金となっているのでしょう。彼女がすぐに受け入れたのは、おそらく彼女のボキャブラリーや言語で、それらがシノハラのように純粋なものであってはいけないということでした。多分、シノハラほどにはアグレッシブになれなかったのでしょう。彼女は作家としての目標を達するためにも、あるバランス、ゲーム、そしてシステムを作り出す必要がありました。

彼女は住宅が作品化することへの疑問を呈しつつも、柿生の住宅において、弾丸をひらりとかわし、雨つぶの間をすり抜けるようにして、まさにその方法を見つけ出しているのです。ほとんどポルノ的に住宅を作品化する方法を。それを誇らしげに見せるわけでもなく。

彼女の芸術的な目標とは何だったのでしょうか?

長谷川逸子は、L字の空間のことを寝室、リビングなどとは絶対に呼ばないのです。代わりに「主室1」、「主室2」と呼んでいるのです。このことから多くのことがわかりますね。サービスブロックの部屋には全て、キッチン、風呂、洗面所、寝室などの名前がついていますから。つまり、住宅は特定の用途のためにあるのではない、ということを示唆しているのです。それは、空間に関することなのです。

副次的な部屋というものは、実利的な理由で存在するものですが、結局は何が重要かをフレーミングする効用があるのです。発表された写真に、サービスブロックの中で唯一写っているのは、階段ですね。圧縮された空間を通過させるだけの基本的な装置ですが、ここでは、二階にある二つ目のL字空間へと至るまでに、一階空間での経験をほとんど忘れさせてくれるような効果があるのです。

一階のL字空間は二つに分断されています。一方にはキッチンに面してダイニングテーブルが置かれており、もう一方はいつも空っぽの状態です。どちらも写真でも出版物でも見ることができますね。ここは玄関スペースであり、通行のためのスペースでもあり、これからこの住宅が披露してくれるものに備えるための「ウォッシングルーム」だとも考えられるでしょうか。長谷川逸子は、その一角に固定式の家具をいくつか配置していますね。ここには古典的な三位一体の関係 - 玄関、リビング、ダイニングがあるのです。これらの機能は全て、サービスブロックでの行為と関連しながら合理的な感じがします。

普通の住宅では、リビングが一番大きな空間を占めますよね。しかしこの住宅では、上階の主寝室もリビングとほとんど同じ面積を占めているのです。写真でも図面でも、二階のL字空間にはシングルベッドが二つだけ、部屋の片側に配置されています。残りは空っぽのまま。L字空間のそれぞれの端には机があって、この部屋が寝るためでもあり、仕事するためでもあるということを意味しているかのようですね。他には家具はありません。

下階に対しての破滅的な片割れという感じなのでしょうか。床はとても暗いのですが、代わりに壁は全て真っ白です。扉は白い壁面に完全に溶け込むように白のフラッシュ戸で作られています。どこの窓からやってきたのかわからない自然光が、側面から現れ、それが勾配天井にあたり、曲面に影を落とす、その自然光による人工的な魅力は卓越していて素晴らしいのです。

一階では、住宅の社会的空間としてのプログラムに対する伝統主義的とも呼べるような視点に関して、非常に明快な意図がありました。

一方、二階は通常の寝室としては明らかに広すぎるので、自然と別の部屋へと変わってしまうのです。この不均衡な関係と特異性によって、長谷川逸子は、機能こそがデザインの主なモチベーションなのではなく、別の性質、別の象徴的なものがあることを示しているのです。

「象徴的」という言葉を使われましたが、それは何を指しているのでしょうか?

象徴的性質というのは、合理性と関係があると思うのです。本当に象徴的な空間や要素というものは、なぜそこにあるのか、なぜそうなのか、とあなたに考えさせてくれるのです。

日常的ではなく、分類しづらい、それでいて奇妙な魅力があるもののことです。それは、機能や技術的な説明を超えた解釈や、考えを与えてくれ、議論させてくれるものなのです。

玄関ホール、リビング、寝室、などといった観点から住宅を捉えるような古典的なやり方で、機能を考える方法は、個人的には非常に時代遅れな考え方だと思いますね。私たちは実践において、明確な実利的解答を見いだせないような配列関係を探っているのです。つまり今日、私たちがしているような刺激的な議論のきっかけとなるアンカーを探し出すためにも、曖昧で抽象的な観念を取り入れているのです。

私たちが研究していく中で、日本の事例から学んだことはまさに、現実と非現実の境界を曖昧にすること、つまりは、家に住むという固定観念を取り払い、別の選択肢を与えることの重要性なのです。私たちも、そういった事例の家族の一員となりたいと思っていますし、上手くは定義できないような「もの」を求めているのです。私たちは、それを空間や要素の象徴的、記号的性質と呼んでいるのです。

日本の建築家が、この性質に対して非常に敏感になったのはなぜだと思われますか?

それに関しては推測が可能です。日本語は、私たちが一言で表現してしまうようなことを定義するために、いくつかの記号を使いますよね。例えば、白、背景、などを定義する記号は、いくつもあるのです。ヨーロッパ的な視点からは、何もない白い背景、を理解することは非常に明快なことなのですが、日本では、どのように何もないのか、どういった白なのか、などを明らかにしておきたいのでしょう。同じことが、柱、にも当てはまります。私たちは、コラム、ポスト、ピラーなどいくつかの定義を持っていますが、それらはほとんど同じものを指しています。日本語では、柱、が何を意味するのかはその柱の位置によって様々な定義があるのです。もしそれが構造の中心に位置している場合は、特定の名称を持ちますし、外周部に位置している場合はまた別の名称を持ちます。下級建築とも呼べるような建物にある場合と、寺院のように重要な象徴的建築にある場合とでは、別の意味を持つのです。それぞれの言葉の意味を具体的に考えることは、結果的にそれぞれのモノの意味を具体的に考えることなのですが、それは日本の文化に深く根ざしていることなのです。

しかし、私が最も重要だと思うことは、この時代の建築家たちが、ある結実した成果に到達できたということだけでなく、彼ら自身が自らの作品についての理論化を途方もないほどに試みていたということなのです。これらの建築家たちはみな、いくつかの雑誌に掲載された文章の中で、自身が行っていたことを記述しています。80年代の「新建築」は毎月10万部発行されていました。宮脇檀、坂本一成、そして長谷川逸子らの論考が定期的に一般の人々の手元にも届いていたのです。一般の市民もたまには、こういったテキストを読んでいたのでしょうね。写真だけではなく膨大な情報が流布されていたのです。建築の論考があらゆる人へと届いていたのです。

現代の日本建築のマンネリ化は、そういったことがなくなってしまったことに大きく起因しているのだと思います。伊東豊雄が最後にそのような文章を書いたのも、おそらく30年も前のことでしょう。現代の日本のスターアーキテクト世代は全く異なる方向へと進んでいます。アトリエ・ワンのリサーチについて言及するにも、それはイツコの時代とは全く異なるものですよね。今日では、アトリエ・ワンのような建築家たちは、建築的空間を創造する理論よりも都市のスケールに関心を持っています。

70年代、80年代の日本の建築は、経済的、社会的事象によって生じた、ある現象で、それを支えていたのは狂気的なほどの出版物への情熱なのです。そのおかげで、全世代の建築家たちは足を止め、考え、実験し、解釈し、お互いにコミュニケーションを取り合い、それが結果として大衆へと届くこととなったのです。ミヤワキは美しい文章を書いていて、このような努力は全て世界を変えるためになされたことなのだと結論づけているのです。そこには闘志と使命感があったのです。彼らの敵はいつしかメタボリストではなく、プレファブ住宅へと変わっていきました。印象派の作家たちが写真に対抗したのと同じように、建築家たちもまた、彼らに取って代わろうとするものへ対抗するための活力が必要でした。

私たちの議論しているこの住宅が建てられた時代は、あらゆることが急速に変化した時代だったのです。土地の価格も急激に上昇していきました。いくつかの住宅はたった二、三年しか存続しなかったのですが、それも土地の価格が上昇し続けているために、すぐに買い換えることができたからなのです。建築家たちは、彼らの住宅が長く存続しないことを知っていたのです。そういった事情から、日本のクライアントたちは、より柔軟で、型にはまらない設計を許容できたのです。ヨーロッパでは、私たちは住宅を一生のものとして建ててきました。対して、彼らは10年単位で建ててきたのです。これは大きな違いです。

この現象をマクロで見ると、非常に興味深いものがあります。出版物はまさにゲームチェンジャーであったわけです。現在、日本に存在するプレファブ住宅は、40年前に建築家たちが理論化したデザインに深く影響を受けています。「カサベラ」や「ドムス」もヨーロッパでは、このようなことは、成し得ませんでした。これらの日本の出版物は、日本でのこうした状況に貢献してきたのです。

柿生の住宅に話を戻したいと思います。出版物では伝えきれなかったことがあるとすればそれは何だと思われますか?

この住宅の出版物では表現しきれなかったこと、それはこの住宅の音響的効果の探索

でしょうか。この住宅へと入っていくことを想像します。5人の人がテーブルを囲んで食事をしています。その姿は見えないですが、声は聞こえますね。夕食の時間を想像してみます。側面から自然光が入ってくる事はなく、何かしらの人工照明がテーブル近くにあるのではないでしょうか。そうすると、この白い曲面全体に人の影が映し出されるでしょう。出版物の写真は、人が住み着いたものではなく、演出されていて、これらの空間の劇的な要素が示される事はありません。

これは、アルヴァロ・シザとエドゥアルド・ソウト・デ・モウラとの間で交わされた興味深い議論のポイントでもあるのです。何年も前の事になりますが、ポルトの大学で、彼らは、海の前に建つ住宅の窓は小さい方が良いのか、それとも大きい方が良いのか、という議論をしていたのです。彼らはお互いに反対の意見を持っていました。ソウト・デ・モウラは部屋からは海全体が見えるようにすべきだと考えていたのですが、シザは、そうじゃない、海を見に行こうという気持ちにさせるためにも、窓は小さくするべきだと言ったのです。そっちの方が努力を強いるものですけどね。

この世代の日本人は、人を惹きつけ、刺激し、移動させるような仕掛けを考えていたという点で、シザの方に賛同していたでしょう。この住宅内における、影との戯れや社会的な振る舞いは、私たちが見ることのできる出版物からとは、全く異なる深い効果を持っていたと思います。

柿生の住宅は白の家と呼べるでしょうか、それとも黒の家と呼べるでしょうか?

どちらとも言えないと思います。ここでの白は、ただ付随的なものだと思います。シノハラの第二様式の住宅のようなポレミックな白ではないですよね。抽象的な白でもない。何よりも、目的のための手段なのです。年表で見てみると、柿生の住宅はシノハラの第二様式の終わりと、第三様式の始まりとの間に建てられているのです。この白はただ、そこで起きる何かに寛容な白だと思うのです。「谷川さんの住宅」においての白が、木の形をした柱や傾斜した土間を空間の主役とするようにね。

柿生の住宅においての白、そして床の暗いカーペットは必要なものだと思いますね。そのおかげで、二つの窓や、ダブルハイトの光源からやってくる光の効果が理解できるのです。

日本では、景色の見えない窓はよくあることです。敷地があまりにも狭く、光もほんの少ししか入ってきません。窓に対する固定観念を打破し、単に外をみるための装置以上のものとして窓を捉え直すためには、何が論点になると思われますか?

日本の都市のカオス、そして建築と都市の関係についてはメタボリストから藤本壮介に至るまで様々な建築家たちによって多くの理論が書かれていますね。これらの世代はいずれも、非常に密集したメタボリックな都市の状況を扱っていますし、そのほとんどにおいて採光と換気の必要性から窓をデザインしているのです。その窓から何が見えるのか、ということではなく、です。

窓は、ある住宅とある場所を結びつける数少ない要素の一つですが、この世代の建築家たちはそれを望んではいなかったのです。

柿生の住宅の窓の写真においては、窓は燃えてしまったように - つまり窓の外はただ白くなっているだけなのです。これは、シノハラが理論化した住宅の自律性に対しての別の表現なのです。住宅には敷地がなく、コンテクストにも属さず、どこにでも存在し得る、という自律性です。もし窓から景色が見えないのであれば、その意図については語らざるを得ないでしょう。

柿生の住宅では、曲面の壁に穿たれた窓が、一階の主室に自然光をもたらしている外壁の窓と向かい合っているわけですが、長谷川逸子は、その角度によって、両方の窓から同時に外を見通すようなことができるかどうかなど気にしていなかったのだと思います。それが主題では全くないですからね。

窓は全て正方形で、完璧にフレーミングされています。この住宅と、それを取り囲むコンテクストを繋ぎ止める事実上のアンカーとしてではなく、むしろ壁に描かれた絵画のようなものなのです。

この住宅を別の用途として使う事は想定できますか?この住宅を自分のものにしたいと夢見るような事はありますか?

主室にベッドを置くことはまずないでしょうね。サービス部分に配置すると思います。上階は仕事をする空間、そして下階は人との関わりを持つような空間とするでしょうか。例えばですが。二つの主室は、夏の部屋と冬の部屋、あるいは読書する空間と、仕事をしたり音楽を聴く空間でもいいでしょう。L字の空間はただ寝るだけの部屋としては強すぎると思うのです。そこは、別の次元、象徴的な次元へと外挿されるような性質や特徴を持っているのです。まったく空っぽなその空間をたまに通り過ぎていく、そのような事はイメージできますけどね。シノハラの第二様式における亀裂の空間的な質があると思います。そこは椅子をおいておけばそれで十分な空間ですよね。

私にとって、この住宅の最大の挑発的主張は、写真や図面に示された二つのマットレスなのです。二つのベッドをそこに置くことで、長谷川逸子は「サービスの提供者と芸術家との間のジレンマ」を貫いているのだと思います。これが私のせざるを得なかった事であり、やりたいことのために、ここまでやってきたのだ、と彼女は言っているのです。

柿生の住宅に対して、不思議に思うところはありますか?

柿生の住宅が建てられたころ、シノハラは上原通りの住宅や谷川さんの住宅を手がけていました。彼は構造や象徴的な構造物と戯れていたのです。長谷川逸子も空間を作るために構造を利用した住宅を作っていました。例えば、焼津の住宅2がありますね - それは構造が住宅であり、またその逆でもあるのです。ところが柿生の住宅においては、構造が非常にうまく隠蔽されています。梁や柱がどこにあるのかわからないでしょう。ある瞬間を除いては。それは屋根裏から撮られた一枚の写真にあるのです - 全ての面材の収束点に柱があり、その柱は屋根に触れているのです。他の階からは、その姿が見えることはありません。言及もされていませんし、そのことを示すものも何もありません。長谷川逸子は、その具体的な写真を一枚、海外の出版物に掲載したのです。柱の姿が現れる、ほとんど知覚不可能な瞬間を、彼女は何らかの理由で外部に公開しようと決断したのです。構造の配置計画や表現が価値を持ち得た時代に、彼女は、住宅の中で、最も重要度が低く、最もアクセスしづらい空間にだけ、その柱の姿を暴露させていたわけです。そのことが、私に問いかけてくるのです。彼女はそのとき一体何を考えていたのだろうか、と。

2021年9月18日

Filipe Magalhães: The limbo in which we, fala, operate - between the lack of interest of the client and the excess of ambition and enthusiasm on our side - is very similar to the situation Itsuko Hasegawa was confronted with, while designing her first houses in the 70s.

YOU PUBLISHED THE DRAWINGS AND PHOTOS OF THE HOUSE IN KAKIO IN YOUR RECENT BOOK ON JAPANESE HOUSES. FROM ALL THE BUILDINGS YOU ANALYSED, WHAT MADE YOU MAKE THIS CHOICE?

It is a house built with very little resources. It’s a banal construction of a boring brief. It’s a discrete, cheap, suburban house. However, the discrepancy between what we could call a very unappealing exterior and a phenomenal interior composition - not in a tectonic sense, but in a spatial and symbolic sense, is surprising. It is almost as if Itsuko designed a house that disappears from the outside on purpose, in order to protect the treasure that hides within.

It has two and a half levels - a social level, a so-called private level, and an attic level. The social level has some program in one corner and a big L - shaped living room in the other corner. The same structure applies to the private level, with some bedrooms in the first corner and a big master bedroom in the second corner.

My reading, however, tells me that the conventional understanding of this house - a social part, a private part, a bedroom, a living room, a space for family members, a space for guests - all these words that we usually use to define the daily life of a house, turn out to be completely irrelevant and insufficient to grasp the real quality present.

If you take all the furniture away from the plans, you end up with a house based on two games - a game between the main and the secondary spaces on each level, and a game between the outside rectangular shape and the inside curved shape, which create important differences and interdependence in the L-shaped rooms on each level. You discover a play of angles, surfaces and light that make sense, independent of any use. It is remarkable that there are no material or structural special effects: there are just walls, windows, ceilings, and floors. Everything is out of white painted plywood. In this sense, it is the work of a master, whereby she truly understood the tools and limitations present and used them only to her advantage. All this is just fantastic.

IN THE TEXT ITSUKO HASEGAWA WROTE ABOUT THE HOUSES SHE BUILT IN THE 70’ („MY WORK OF THE SEVENTIES” IN SD 04/85) SHE SURPRISINGLY UNDERLINES HER INTEREST IN „THE CONCERNS OF LIVING RATHER THAN ABSTRACT METHODS OF ARTISTIC EXPRESSION”. THE HOUSE IN KAKIO, AS YOU STARTED TO EXPLAIN, IS DEFINITELY NOT ONLY ABOUT THE „CONCERNS OF LIVING”.