堀部安嗣: 私の師匠である益子義弘先生が、アアルトのことが好きで、君もぜひフィンランドに行って、アアルトの作品を見るといいよ、と言ってくださったのがきっかけです。実は、当時はアアルト自邸を見ても今ほどピンときませんでした。なんだ普通の家じゃないか、という感じで、そこまで刺激がなかったことを覚えています。ただ、フィンランドの風土や、日本人に近くシャイで温厚な性格のフィンランド人との触れ合いを通じて、フィンランドに対してのシンパシーみたいなものを、非常に強く感じ、また行きたいという風に思いました。その後、フィンランドには都合4、5回は行っていると思います。最近は、アアルトの作品、特に自邸に対しての素晴らしさを強く感じるようになってきました。これは自分の経験や年齢、あるいは、建築に対する理解みたいなものが深まってきたからなのではないかと思います。

あるテキストの中で、興味深い説話を引用されていたと思います(「建築への憧れと絶望」『JA 90』2013) 皇帝が宮廷画家に「描くのが難しいものは何か」と尋ねると、宮廷画家は「鬼を描くのは簡単だが、犬は難しい」と答えた。見慣れたものに対して私たちは、すぐに間違いに気づいてしまうからだ、と。それは、建築に対しても同じことだとおっしゃっていますが、アアルト自邸は、犬的なものなのでしょうか?それとも鬼的なものなのでしょうか?

時間の経過によっても変わるものだと思いますが、おそらく建った当初は、かなり鬼的な要素があったと思います。けれども、時代や社会の変化、それに建築の技術や文化の変化を経て、年々、犬的な側面が強くなってきたのではないかと思います。

いい建築には、そういう変化があるように思います。当時は、非常にラディカルで過激だったものが、今となってみれば、とても穏やかで、表現が丸くなっているということがよくあります。アアルト自邸が犬的な側面を持ち始めたのも、等身大の人間の心身のことを、アアルトが理解していたからだと思います。

人間の心身への正直さみたいなものを外した鬼的な表現というのは、やはり長く保たないもので、人から飽きられてしまう性格のものになるのではないかと思います。

建築には大きく分けると、二つの役割があると思います。一つは花火のような役割で、花火を打ち上げて人々を鼓舞したり、奮い立たせたりして、元気を煽っていくような、お祭り的な役割というのも当然あると思います。一方で、漢方薬のような時間と共に効能が現れてくるような、地味だとしてもどんな心身の状態にも無理や負担のない、そういった建築の役割も必要だと思います。最も美しいものだと私は思っていますから。

アアルト自邸は、サイズが控えめで日々のエネルギー消費も少なく、サスティナビリティという点において非常に良いモデルになるのではないかと思います。こういった住宅がやはり、生活空間としては適切であるとお考えでしょうか?

建築のサイズ感というのは、人と人との距離感のことだと思います。そして、アアルト自邸のサイズというのは、彼の考える人と人との距離感の適切な解であったのだと思います。また、彼は建物内部のことだけではなく、隣人や地域の中での距離感といった複合的な内外の人との距離の調整やデザインが、非常に達者だったのではないかと思います。

例えば、マイレア邸は非常に大きな住宅ですが、そこに大勢の人が集まった時のことも考えていたのだと思いますし、あの地域の牧歌的な風土や雰囲気の中での、人と人との適切な距離感を考え、あのサイズ感になっているのだと思います。

つまり、何平米だとか数値的な広さというよりも、人と人との距離感、自然との距離感、そして、人工と自然との距離感を測る役割として、建築を考えていたのだと思います。アアルトは、その辺のバランス感覚が非常に長けているのだと思います。

適切なサイズ感というものは、主観的なものなのでしょうか?それとも客観的なものなのでしょうか?

例えば、京都の町家は、鴨居も非常に低くて、身長が175センチぐらいある人は、必ず頭をかがめないといけなかったりしますし、必ずしもどんな体型の人にも快適かと言えば、そうではないと思います。けれども、おそらく身長が180センチ以上の人がそこに行っても、意地悪を感じたり、居心地の悪さを感じるかというと、そんな事もないと思います。それは、その文化や寸法体系を作った人々の、誠実さや正直さが、空間に表れているからだと思います。そういったものは、街全体から感じられるものです。周囲のスケール感であったり、道路の広さであったり、隣の家との間隔みたいなものを相対的に体の中で感じとって、この街、あるいは、ここでの伝統や文化の中では、このスケールがちょうどいいことなんだということを、瞬時に感じ取れる力が人間にはあるのではないかと思います。それが、馴染みのないスケール感やサイズ感であったとしても理解できるような、ある種の感受性があるのでしょう。

大事なことは、ドアの高さが180センチしかないことが国際的ではないとか、ユニバーサルではないとかそういうことではなく、地域であったり、風土であったり、歴史であったり、そういったもののもつスケール感や雰囲気と、具体的な一つの建物の内部の雰囲気やスケール感がフィットしているということなのではないでしょうか。例えば、逆に私たち日本人が、アラブの石油王の家に行ったとします。それが体験したことのない寸法や、スケール感であったとしても、ここを作った人たちは誠実に、ここでの文化や慣習の中から、このスケール感を導き出していることを、私たちは感じることができるのだと思います。

ですから、そこに何かを無理やりクリエーションするよりも、それらの流れに身を任せ、一個人のクリエーションを超えた何かに教わっていく。そういった謙虚さが大事じゃないかなと思います。

日本の建築家として、現代の西洋の文化に対する印象や、お考えを教えていただけますでしょうか?

一神教の国と多神教の国、その考え方の違いというのは、非常に大きいなと思います。どっちが良い悪いということではなく、単に自分自身や周囲との関わり方への違いがあるのだと思います。

私は一つの神を信じている人間ではなく、どんなところにも何か自分を見守ってくれる存在がいたりだとか、自分を支えてくれるものが自然界の中にあったり、友人の中にあったり、さまざまなところに存在しているという、そういう考え方からどうしても抜け出せないところがあります。それはもう身体にもすり込まれてる、という感じでしょうか。

一方で、フィンランドというのは、我々とその辺の感覚が似ていて、自然の中にも、いくつも精霊が宿っているという考えがあると思います。典型的なのが、ブリュックマンの教会や、オタニエミのシレンの教会でしょうか。ああいう森の中に神様がいる、というような感覚に出会うと、非常に心が穏やかになるというか。西洋の中にある、ああいうものに触れると喜びを感じますね。

時間に関しての考え方の違いもあるのだと思います。私は、大きく分けると二つの時間の流れ方があると思っています。一つは、一直線に進んでいく時間の流れ方。どんどん技術は進化して、良くなっていくという時間の流れ方です。もう一つは、ぐるぐると循環した流れ方。太陽が昇って、また沈んでいくような、進化もしていなければ、進歩もしていないという循環的な流れ方です。大きく言うと、理系の人は、技術はどんどん進化して、人間はどんどん賢くなるといった進歩史観を持っているのだと思います。例えば、10年前のiPhoneは今と比べると使いものにならないですよね。一方、文系の人は、200年以上前のモーツァルトの曲や、ドストエフスキーの書いたものが今よりも劣っているとは考えません。

今は、西洋の方々も、そういった一直線に流れる時間に対して、大きな疑問を感じてきている時代なのではないかと思います。人間は、別に進歩も進化もしていないというような循環した時間の流れ方に、西洋の方々も気づき、国籍や人種を超えて共鳴し合う世界へとなっていくといいなという風に思っています。

あえて、東洋とか西洋という代名詞を使って説明していますが、そういった代名詞を使わずに、直線型なのか、循環型なのかという言い方をした方が的確ですね。

多神教やフィンランドの建築に共感を示されている一方で、あなたの作品には、西洋的な強い幾何学の厳密性を感じます。それはなぜでしょうか?

実は、アメリカに行って一番東洋的だなと思ったのは、キンベル美術館でした。他のどんな建築よりも、遥かに東洋的な建築だという風に感じました。キンベル美術館は、まさに整理整頓、秩序の世界ではあるのですが、その秩序というか幾何学というものが、先ほど述べたように、進化的なものではなく、回転していくというか、循環していくというか、またどこかに行ってまた戻ってくるというか、そういった奥行きと深さを持っているように思いました。

例えば、循環を表している絵には曼荼羅がありますが、曼荼羅にも非常に厳格な幾何学が用いられていて、テンポやリズムの中に円を意識していくというか、幾何学の中に丸を意識していくというような感じがあります。そういうところに、私は非常に興味があります。

複雑なのだと思います。シンプルではない。非常に複雑でいろいろな複合的なものが絡み合って、さまざまなアンビバレンツなものが同居しているというか。それを三次元的、あるいは四次元的に表しているのが曼荼羅であり、キンベル美術館ではないかなと思います。厳密な幾何学が循環的な世界と相反するものであるかというと、必ずしもそうではないと思います。つまり、キンベル美術館には、サイクロイド曲線がありますし、曼荼羅にも円の形がありますが、平面や断面でそういった形を使うことが重要なのではないと思います。

本当に一言では言えないですよね。良い建築って。四次元的に循環している、あの世界を言葉で表すというのは難しく、体感する以外ないのだと思います。設計者の考えも本当に行ったり来たりしながら、元に戻ったり、無駄がいっぱいあったりするのですが、そういった複雑な思考を続けたからこそ、あの奥深さがあるのではないかなと思います。直線型の思考からは出てこない複雑さだと思います。

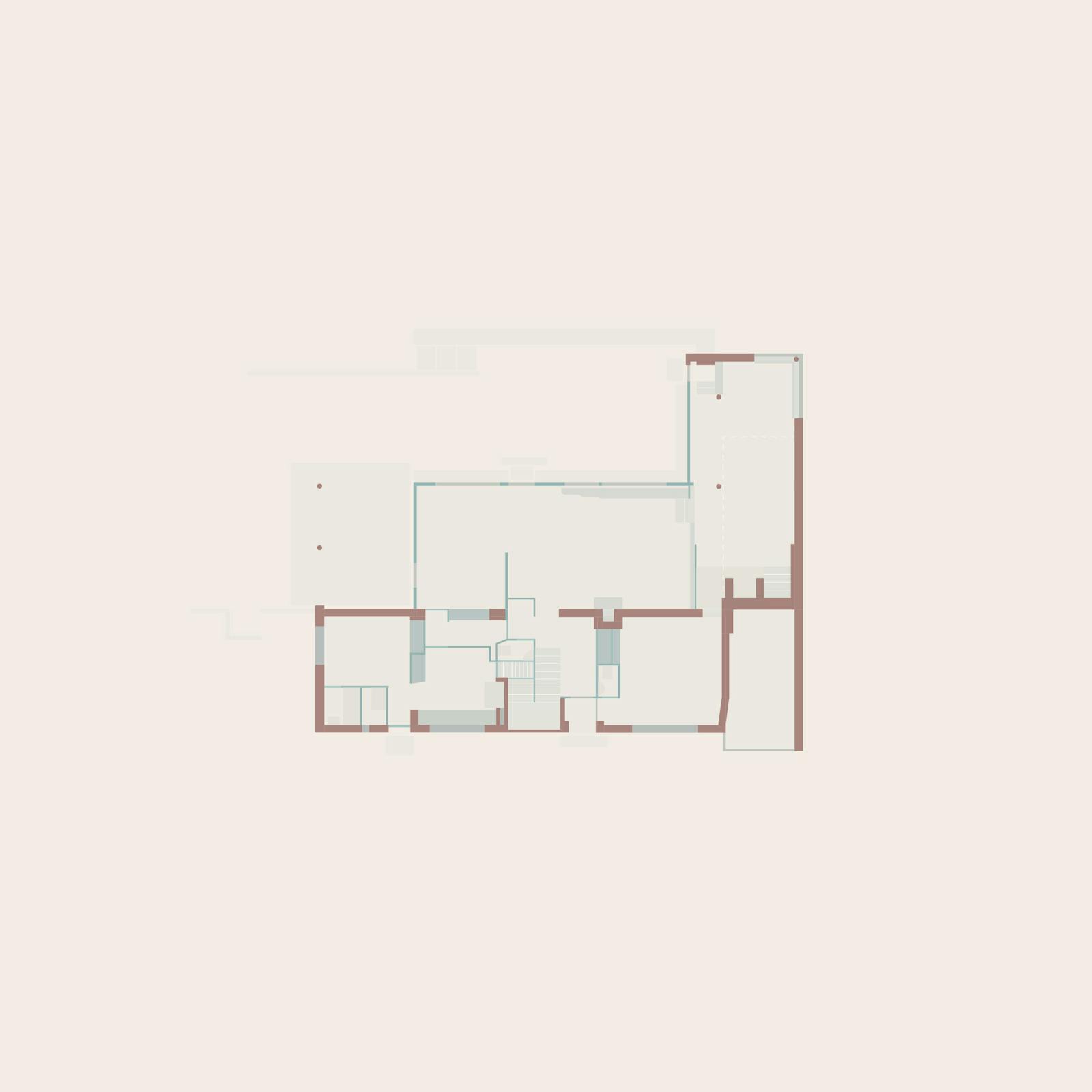

自然との関係に関して言えば、マイレア邸もアアルト自邸と同じように、L字型のボリュームが中庭を囲んでいます。あなたは著書『建築を気持ちで考える』の中で、マイレア邸の中庭は、方角に従って素直に南側に向けて配置した方が良かったのではないか、とおっしゃっていますが、実際は、太陽の方角に反して、アプローチのある南側と逆方向に中庭を開き、自然との関係を作ろうとしています。アアルトが太陽の方角よりも、周囲の自然から背を向けることを優先した理由は何なのでしょうか?

アアルトの建築がなかなか言葉にしづらく、そして単純な言葉では語れない理由は、まさにその複雑さと繊細さにあるのだと思います。自然に対しての連続性を意識したり、風土を生かそうという気持ちがある一方で、自然の厳しさに対して、人の安心できる居場所を作らなければいけない、という相反する自然への向き合い方みたいなものが共存しているからだと思います。一番わかりやすいのは、ユヴァスキュラの夏の家ですね。自然の大地にしっかりと根を下ろしながらも、高い壁を建てて自然をフレーミングしたりして、自然から身を守るような設えをしています。そういった複雑な自然への向き合い方や、人間と自然との微妙な関係性を、アアルトは深く考え続けていたのではないかと思います。

フィンランドは、とにかく寒いですし、歓迎されない動物も入ってきたりしますから、自然を遮断することの重要性というのは、あの風土においては当然考えなければいけないことなのだろうと思います。

アアルト自邸の前に立つと、道路側のファサードには開口部が少ないことに気づきます。黒と白の外観は、無表情で自閉的なものにも見えますが、その点についてはどうお考えでしょうか?

とはいえ、道路沿いや隣地境界には、日本のような塀がないことがわかると思います。隣地境界には、塀の代わりに、牧場の丸太の柵のようなものがあるだけなのですが、何かフィンランドの大地の連続性みたいなものが意識されているのではないでしょうか。

今日の、特に日本では、土地や住まいに対する所有への欲望というものが、とても強いように思います。ここからここは自分の持ち物だ、というようなことが過激に表現されているのですが、それは逆に、それだけ土地に余裕がないことの表れなのだと感じます。

ところが、その土地をその人が100%所有しているのかというと、もちろんそうではなく、そこに入ってくる風はみんなのものですし、そこに降り注ぐ太陽もみんなのものです。そこの土も、隣の家からずっと繋がってきているものですので、そこに線を引くということはなかなかできないわけです。地下や上空も、ある距離を超えると、もはや所有物ではなくなりますよね。アアルトは自分だけが独占するような、町や家を作るのではなく、やはり大地の連続性というものをとても意識していたのではないかと思います。それは、あの自邸にもすごく表れているように思います。

「真っ白い抽象的な壁に当たる光を見て美しいと思えるのは、気持ちが未来に向いている人や想像力が豊かな人だけなのです。」(『建築を気持ちで考える』TOTO出版 2017年)とおっしゃっていましたが、アアルトはなぜそうしたモダニズムの抽象的な美学を自邸において表現しなかったのでしょうか?

モダニズムというのは人間、あるいは建築家の設計主義的な理想像を強く掲げることで、人間の無謬性みたいなものを信じていたのだと思います。例えば、理想の設計図を描いて、理想の都市像や社会みたいなものを描けば、その通りに実現していくというような、どこか人間の驕りのようなものがあったように思います。設計者が神の視点に立って全てをコントロールすることができ、世界中どこにでも同じスタイルで住宅や建築が可能であるという、今となってみれば驕りとしか思えないようなことが繰り広げられていたのだと思います。

つまり、人間の強さみたいなものを非常に信じていたんだと思います。ところが、その人間の強さみたいなものを基準として、建築やその時代の背景を作ったとしても、人間というのは老いていくもので、元気なときばかりではなく、権力を失うときもあれば、お金がなくなるときもある。そういうときが必ず来ますよね。いいときばかりではない。

フィンランドは、そういった観点から見ると、人間は弱いものであるということを自覚できる風土なのではないかと思います。つまり、非常に寒い。それから晴れる日が少ない。そんな過酷な環境の中では、ただそこにいるだけで憂鬱になっていくような人間の弱さに対して、肉体的にも精神的にも向き合わざるを得ないわけです。そういう環境への葛藤が本質的にあるのだと思います。フィンランドの建築や文化は、そういった状況から出てきているものだと思いますし、私はそういうところに非常に共感します。そのことが、元気な時も病めるときも、心身を包み込んでくれるようなフィンランドの建築の質の高さにつながっていったのではないかなと思います。

やはり国も元気なときもあれば、そうでないときもあります。社会に元気がなくなってきたときに、自信や希望に満ち溢れていた時代に作られたものというのは、どこか狂気に感じられたり、怖いものになっていくのだと思います。

あるテキストの中で「街や建築が闇を嫌い、異常なまでにフラットで清潔になってしまった」ということを書かれていたと思います (「人に寄り添うかたち」『JA 90』2013) アアルト自邸はまさに、清潔さや衛生面、それに健康といったことに取り憑かれていたモダンムーブメントの渦中にあった住宅ですが、そこに陰りや曖昧さのようなものは、感じられるのでしょうか? また、どの部分にそういった性質が残っているとお考えでしょうか?

モダニズムの問題みたいなことに触れましたが、モダニズムが切り開いたポジティブな側面もたくさんあると思います。それは、アアルトの仕事の中にも非常に良い形で表れていると思います。例えば、大きなガラスは、モダニズムの産物ですが、フィンランドでは特に、冬に太陽の日差しや熱をたっぷりと取り入れるために非常に有効なものだと思います。そういったモダニズムの性能の高さと、ディテールにおける手仕事のあたたかさや、自然素材の使い方とが良い形で融合しているというところには魅力を感じますね。

そして、アアルトにおける暗がり、あるいは神秘性というものは、サウナに表れているのではないかと思います。多くのアアルトの住宅にはサウナがあり、それらは非常にトラディショナルな形をしています。そこはモダニズムの精神から切り離された、土着的で暗がりをもった神秘性のある場所になっていると思います。

アアルト自邸は、家でもあり仕事場でもあるという、他の住宅とは決定的に異なる特徴があります。一階のリビングは、仕事のミーティングでも頻繁に使われていたようですが、こういった仕事場と生活空間の関係性については、どうお考えでしょうか?

この自邸を選んだ理由は、アアルトのフェアさみたいなものに惹かれたからです。アアルトの態度には、それが自邸であるとか、他人の家であるとかといった違いを感じません。他人には非常に実験的な家を作る一方で、自分の家は保守的であるという建築家も数多くいますが、アアルトはそうではない。そのリベラルさというか、人間的なフェアさみたいなものを非常に強く感じます。そのことは、職住が一体になっているということにも繋がるのだと思います。

アアルトは住宅を基本に考えていて、仕事場も住宅であり、そこが人間の巣であり、人間の居場所であると考えていたのではないかなと思います。それが教会であっても、ホールであっても、大学であっても、それに村役場であっても、多くの人の心身を温かく受け入れてくれる住宅というものが、考えの起点になっているのだと思います。人の気配や、ぬくもり、あるいは手仕事みたいなものが、ああいう厳しい風土の中では、どれだけ貴重なものなのかを、アアルト自身よくわかっていたのだと思います。モダニズムは工業化や、量産化の有用性から語られることが多いですが、アアルトは、そういったものを大事にしながらも、人のぬくもりを感じさせるディテールや構法、それからプランニングをしていったのではないかと思います。

人は、一人では生きていけないということとも関係しているのだと思います。人も群れをなす動物の一種ですので、みんなで集まれば、それだけ温かくもなります。それに、人の気配が感じられないということは、人口密度の低いフィンランドにおいては、非常に怖いことなのではないかなと思います。

建物の一つ屋根の下では、人の気配を感じながら、みんなで本を読んだり、図面を引いたり、何か押しくら饅頭をしているような状態でいる。当時のフィンランドは、そういったことに関して、いまの我々以上に許容できた社会であったのかなと思います。

あの住宅の雰囲気、そして事務所を併用しているということに関しては、アアルトだけの性格からくるものではなく、当時の奥さんであるアイノの存在というものも非常に大きいと思います。当時からアアルトは男女の平等、つまり女性も社会に進出して、男性と何ら変わらなく建築の仕事ができるという、そういうことへの理解があったんだと思います。そこにも、アアルトの特徴がみてとれます。アアルトが社会的にも先進的な眼差しを持っていたということが、あの自邸に行くとよく伝わってきます。人間的なフェアさに対する眼差しですね。

2022年12月29日

Yasushi Horibe: My teacher, Yoshihiro Masuko, held a great admiration for Aalto and told me to travel to Finland to see his works. To be honest, upon my initial visit, I was not particularly impressed with Aalto’s own house; I remember thinking, “It’s just an average house.” However, the natural features of Finland and the interaction with the reserved and gentle Finnish people – akin to the Japanese – evoked a deep sense of personal empathy towards Finland. Since then, I have returned to the country on four or five occasions and recently, come to appreciate Aalto’s work, particularly his own house. I attribute this to my experiences, my age, and my growing understanding of architecture.

IN YOUR TEXT (“MY ADMIRATION AND DESPAIR FOR ARCHITECTURE IN JA 90/2013”), YOU NOTED AN INTERESTING ANECDOTE: A KING ASKING A PAINTER WHAT WAS THE MOST DIFFICULT THING TO PAINT. THE PAINTER REPLIED THAT IT WAS EASY TO PAINT A DEMON BUT NOT A DOG—WE WOULD IMMEDIATELY RECOGNISE MISTAKES IN THE REPRESENTATIONS OF WHAT WE KNOW VERY WELL. YOU ALLUDE TO ARCHITECTURE, SAYING THAT DESIGNING A CALM-LOOKING BUILDING IS LIKE PAINTING A DOG. IS ALVAR AALTO’S HOUSE MORE LIKE A DOG OR RATHER LIKE A DEMON?

I think it has changed over time. Probably, when it was initially constructed, there was a very demon-like appearance to it. However, due to changes in both social and architectural techniques and culture, I think the dog-like aspect became more prominent.

In many cases of good architecture, this process usually happens; what once was very radical and avant-garde soon becomes soft and more relaxed in expression. An important factor in Aalto’s house becoming dog-like with time is that Aalto understood a life-size person’s body and mind.

If the expression is demon-like and insincere to the human body and mind, it will not last long, and people will become fatigued with it.

Generally speaking, I think architecture has two primary roles. One is like launching fireworks, which raises people’s spirits; a celebratory role of architecture that encourages and inspires. On the other hand, there must also be architecture like Chinese herbal medicine, which shows its effects over time and which is not overpowering or burdensome to any physical or mental condition; it is quiet.

AALTO’S RESIDENCE IS MODEST IN ITS SIZE, EMBODYING A MODEL OF HIGHLY EFFICIENT SUSTAINABILITY, AND CONSEQUENTLY LOWER DAILY ENERGY EXPENDITURE. DOES THIS HOUSE REFLECT YOUR VIEWS ON HOW DOMESTIC SPACES SHOULD BE BUILT?

I think that the size of architecture is intimately tied to the concept of distance from others. The dimensions of Aalto’s own house are a fitting example of his ideas about the appropriate distance between individuals. Furthermore, Aalto had a keen ability to not only design the interiors of buildings but also carefully consider and create appropriate distances between the inhabitants, whether they be within the building or in the surrounding community.

For example, the Villa Mairea is a large house; however, it was designed with an eye to the social dynamics that occur when many people congregate in one place, and how the distance between people should be maintained in the idyllic atmosphere of the area.

Rather than considering only numerical measurements, such as square meters, he conceptualized architecture as a means of measuring the distance between individuals, between people and nature, and between the man-made and natural world. I think Aalto had a very refined sense of balance in that regard.

IS THE FEELING OF A SUITABLE SIZE SUBJECTIVE OR OBJECTIVE?

An example of this is a machiya townhouse in Kyoto, where the lintel is so low that a person of about 175 cm in height must bend to enter, which may not be comfortable for individuals of all body types. However, it is not necessarily true that those taller than 180 cm would feel uncomfortable or ill-at-ease. This is because the space embodies the sincerity and honesty of those who created it, along with their cultural patterns and systems of sizes. This atmosphere can be sensed throughout the entire city. I believe that humans can instantly sense that the size of the building or its interior is appropriate for the context, tradition, and culture of that particular town or area, while feeling the scale of surrounding area, the width of roads, and the sense of distance between neighbouring houses. Humans have a certain receptivity to understand unfamiliar scale or size.

What is important is not whether the door height of 180 cm is international or universal, but rather, whether the atmosphere and scale of a specific building align with the scale and atmosphere of the region, climate, history, and other relevant factors. If we were to visit the house of an Arab oil tycoon, despite the unfamiliar dimensions and scale, we would likely sense that the people who built it were sincere and followed the sense of scale derived from the culture and customs of the region.

Instead of forcing something, it is better to let oneself be guided by those flows and learn from something beyond one’s creation. This kind of humility is important.

FROM THE VIEWPOINT OF A JAPANESE ARCHITECT, WHAT ARE YOUR IMPRESSIONS AND INSIGHTS ON MODERN WESTERN CULTURE?

I believe that there is a significant difference between the ways of thinking prevalent in monotheistic and polytheistic countries. It is not about which one is better or worse; these are simply different ways of thinking that affect how people view themselves and how they build relationships with their surroundings.

I just can’t think in a monotheistic way. It has already been ingrained in my body that there are various existences that watch over me or support me in the interaction with nature, friends, or in any place. For me, it is almost impossible to get over this way of thinking.

I feel that Finland is a country that traditionally shares our Eastern sense. There is a belief that there are multiple spirits in nature, and examples of this can be seen in Bryggman’s Resurrection Chapel or Siren’s Otaniemi Chapel. Celebrating the feeling that there is also a god in the forest makes me feel very calm; I find joy when I come across such things in the West.

It has a certain impact on how we think of time. I believe there are two primary ways in which time flows. The first is linear, with technology continually advancing and society progressing. The second is cyclical, akin to the rising and setting of the sun, with no progression or evolution. To simplify, people working in sciences tend to subscribe to the idea of a historical trajectory of progress, wherein technology and human intelligence are constantly improving. For instance, an iPhone from 10 years ago is not as functional as the present-day models. Conversely, people in human studies do not believe that a piece of music composed by Mozart or a literary work written by Dostoevsky over 200 years ago is inferior to contemporary creations.

I believe that we are currently in an era where individuals in the West are beginning to question this linear manner of time applied to all aspects of life. I hope that the West will begin to embrace the cyclical idea of time and that the world will become a place where individuals can connect and resonate with one another regardless of their nationalities or races.

I am using the terms “East” and “West” deliberately, but it would be more accurate to say “linear” or “cyclical” without using such pronouns.

WHILE EXPRESSING SYMPATHY FOR POLYTHEISM AND FINNISH ARCHITECTURE, YOUR WORKS SEEM TO HAVE STRONG WESTERN RIGOUR OF GEOMETRY. WHY IS THAT?

The most Eastern thing I saw in America was the Kimbell Art Museum. I felt that it was a far more Eastern building than any other building I had visited. The Kimbell Art Museum is a realm of organisation and order, but that order or geometry is not evolutionary, but rather rotational or cyclical; going somewhere and coming back again. I felt that it had an incredible profundity.

A mandala represents circularity, but it also uses very strict geometry. There is a sense of circulation by using its unique tempo, rhythm, and repetition within the geometry. I am very interested in that kind of thing.

I think it is not simple; rather, it is very complex, with various ambivalent elements coexisting. The mandala and the Kimbell Art Museum represent this complexity in a three or four dimensional way, and prove that geometric rigour is not necessarily in conflict with the cyclical world. Although Khan’s building has vaults constructed on cycloids, and a mandala is a circle, I would like to emphasise that this is not about merely using circles in plans or sections.

Good architecture cannot be described in just one word. It is really difficult to express the four-dimensional cyclical world using words. I think it can only be experienced. The designer’s thoughts also go back and forth, return to the origin, and traverse through many unnecessary things. I think that this is how depth is built up; it is a result of complex non-linear thinking.

CONCERNING ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ENVIRONMENT, VILLA MAIREA HAS AN L-SHAPED STRUCTURE THAT ENCLOSES A COURTYARD, SIMILAR TO AALTO’S OWN HOUSE. IN YOUR BOOK „THINKING ABOUT ARCHITECTURE WITH FEELING” YOU SUGGEST THAT HAVING THE COURTYARD OPENED TOWARDS THE SOUTH WOULD HAVE BEEN MORE APPROPRIATE AS IT FOLLOWS THE PATH OF SUNLIGHT. INSTEAD OF ORIENTING THE HOUSE TOWARDS THE DIRECTION OF THE SUN, HE CREATED A COURTYARD IN THE OPPOSITE DIRECTION OF THE APPROACH THAT ALLOWED HIM TO INTERACT WITH NATURE IN A MORE PROTECTED WAY. WHAT COULD HAVE MOTIVATED AALTO TO PRIORITISE TURNING HIS BACK ON SURROUNDING NATURE?

I think the very reason why Aalto’s architecture is hard to put into words and can’t be explained by simple words is because of the complexity and subtlety of his designs. Two conflicting ways of interacting with nature coexist: on one hand, there is an awareness of continuity with nature and an inclination to take advantage of the local natural features, and on the other hand, there is a need to create a sanctuary where individuals can feel secure in the face of nature’s harshness. The most conspicuous example is his experimental house, which is firmly rooted in the natural ground but encased by tall walls to protect people from nature. I think Aalto has continued to think deeply about such complex approaches to nature and the relationship between humans and their surroundings in his architecture.

In any case, Finland is cold and unwelcome animals roam, so the importance of blocking off nature is certainly something that needs to be considered.

STANDING IN FRONT OF AALTO’S HOUSE, ONE NOTICES THE ABSENCE OF MANY OPENINGS ON THE STREET-FACING FACADE. THE BLACK-AND-WHITE EXTERIOR MAY SEEM UNWELCOMING AND IMPENETRABLE FROM THIS ANGLE.

Yes, yet let’s not overlook the absence of walls on the perimeter unlike in Japan. There are no walls along the road or at the boundary of the neighbouring property; just a log fence like on a farm, reflecting Finnish land’s continuity.

Nowadays particularly in Japan, there seems to be a strong desire for possession of land and housing. People often excessively express that an area from here to there is their possession. I think this is a reaction to the scarcity of land and space.

However, whatever we believe or feel, it is never true that an individual owns 100% of the land. The wind that blows through there belongs to everyone, and the sun that shines on it also belongs to everyone. The soil there is also connected on all sides to the neighbouring plots. It is not easy to draw a line. Underground or above the ground, when you go beyond a certain distance, it is no longer considered owned by anyone. Aalto did not create houses or neighbourhoods that were exclusive, he was very conscious of the continuity of the land. I think this is very evident in his own house.

YOU TOLD ME THAT “ONLY THOSE WHOSE FEELINGS ARE DIRECTED TOWARD THE FUTURE AND WHOSE IMAGINATIONS ARE FERTILE CAN SEE THE BEAUTY IN THE LIGHT HITTING A BLANK, ABSTRACT WALL.” WHY DID AALTO BREAK THE RULES OF ABSTRACT AESTHETICS IN MODERNISM IN HIS OWN HOUSE?

I think modernism was heavily rooted in a design-centric ideal of architects, and adhered to a notion of human infallibility. There was a sort of human arrogance in assuming that if an ideal blueprint for an ideal city or society were devised, it would be realised exactly as it was intended. Such conceit, which would only nowadays be considered conceited, was the belief that the designer could control everything from a god-like perspective and that it was possible to construct houses and architecture in a similar style anywhere in the world.

I think they possessed great faith in the strength of human beings. However, even if architecture and the background of the time were created based on that kind of human strength, people age, at one point lose health, power and wealth. There will always come a time when one loses everything.

From this perspective, I feel that Finland has a climate where people come to terms with human vulnerability. It is very cold; there are very few sunny days. In such a harsh environment, we are forced to confront our vulnerability both physically and mentally, often becoming depressed just by being there. The struggle is somehow intrinsic. I sense that Finnish architecture and culture originated from such a situation and I empathise with it greatly. This is likely the reason for the high quality of Finnish architecture, which embraces body and soul in both good and bad times.

Sometimes a country is energetic, and sometimes it is not. When a society loses its energy, the things that were created during times of faith and hope can seem crazy or even terrifying.

IN ONE OF YOUR PAST WRITINGS, I RECALL YOU LAMENTED THE MODERN MOVEMENT’S ERADICATION OF DARKNESS, CAUSING FLAT AND BANAL SPACES. AALTO’S HOUSE IS A PART THE MODERN MOVEMENT ENTHRALLED BY NEATNESS, HYGIENE AND FITNESS. COULD YOU TELL ME HOW MUCH SHADOW OR AMBIGUITY IS PRESENT IN THIS RESIDENCE? WHERE CAN THEY STILL BE LOCATED WITHIN THE BUILDING?

I just mentioned the problems of modernism; however, I also believe that modernism opened up a lot of possibilities that could be used in a very positive way. In Aalto’s work, they are studied and bring many benefits. As an example, big glass panes are a product of modernity – and in Finland specifically, prove beneficial during the wintertime due to the significant amount of sunlight and heat they enable into buildings. I find it fascinating that there is a good fusion of the warmth of handwork, the use of natural materials, and the high performance in functionality by the invention of modernism in the details.

I think that the darkness, or the presence of mystery in Aalto’s work, is evident in the sauna. Many of Aalto’s houses have saunas, which are very traditional in form. These are indigenous, dark, and mystical places that are detached from the spirit of modernism.

AALTO’S RESIDENCE HAS A UNIQUE PECULIARITY THAT MAKES IT DISTINCT FROM OTHER HOMES—IT SERVES AS BOTH A LIVING SPACE AND AN OFFICE. THE LIVING ROOM, LOCATED ON THE FIRST FLOOR OF THE HOUSE, WAS FREQUENTLY USED FOR OFFICE MEETINGS. HOW DO YOU ENVISION RESIDENTIAL SPACES INTERACTING WITH WORK AREAS?

I chose Aalto’s own house due to my attraction to his sense of fairness. Aalto’s approach is consistent, no matter if it is his own house or someone else’s. Many architects create highly experimental houses for others while keeping their own houses conservative, but Aalto does not. I feel that he must have a sense of liberalism and fairness. This attitude probably appears in the the integration of home and work spaces.

I think that Alvar Aalto believed in designing all types of buildings based on the principles of housing; namely, that the workplace should also be a home, a nest for humans, and a place where people belong. Whether it is a church, a music hall, a university, or a village hall, the starting point for all of these is indeed a house, that warmly welcomes both the body and soul of people. I believe that Aalto must have understood the significance and value of aspects such as human presence, warmth, and craftsmanship in a harsh environment. In modernism, people often emphasise the efficacy of industrialisation or mass production; however, I believe that while understanding importance of such inventions, Aalto developed details, construction methods, and planning to evoke a sense of human warmth.

As for the integration of home and workspace, I believe it is related to the fact that people cannot live alone. People are a kind of herd animal, and when they gather together, they become warmer. In Finland, where population density is low, not being able to feel the presence of others can be quite frightening.

Under one roof of his house, there is a place for everyone to do something: make dumplings, read, draw architecture, and feel the presence of others. I think that at the time Finnish society was more tolerant and willing to share space more than we are today.

The atmosphere and use of the house in combination with the office are not solely the result of Aalto’s personality. I believe that the presence of his wife, Aino, was also very important at the time. It seems that Aalto had an understanding of gender equality; he believed that women could advance in society and work in architecture no differently than men. This is another example of Aalto’s feature. You can see his socially progressive perspective when you visit that house. It truly tells us about Aalto’s human fairness.

29.12.2022

堀部安嗣: 我的老师益子义弘非常钦佩阿尔托,并告诉我要去芬兰看他的作品。老实说,我初次拜访时,并没有对阿尔托的自宅特别印象深刻;我记得当时想,“这只是一个普通的住宅。” 但是,芬兰的自然风光以及与保守、温和的芬兰人(类似于日本人)的互动,唤起了我对芬兰的深刻共鸣。从那时起,我已经回到这个国家四五次,并最近开始欣赏阿尔托的作品,尤其是他的自宅。我把这归因于我的经历、年龄和对建筑学的逐渐理解。

在您的文章《建筑的敬佩和绝望》(JA 90/2013)中,您提到了一个有趣的轶事:一个国王问一个画家最难画的是什么。画家回答说,画恶魔很容易,但画狗却不容易——我们会立刻意识到熟悉的事物的表现错误。您提到了建筑,说设计一个看起来平静的建筑就像画一只狗。阿尔瓦客阿尔托的住宅更像一只狗,还是更像一个恶魔呢?

我认为随着时间的推移,它发生了变化。可能在最初建造时,它有一个非常像恶魔的外观。然而,由于社会文化和建筑技术的变化,我认为狗的一面变得更加突出了。

在许多优秀的建筑案例中,通常会发生这样的过程;曾经非常激进和前卫的东西很快就会变得柔和、更放松地表现出来。阿尔托的住宅在时间的推移中变得更加狗一般的重要因素之一是,阿尔托了解人的真实体验,包括身体和心灵的体验。

如果建筑的表达方式像恶魔一样不真诚并且与人类身体和心灵的体验相矛盾,它不会持续太久,人们会对其感到疲劳。

一般来说,我认为建筑有两个主要的作用。一种像烟花一样,能够提升人们的精神;建筑的庆祝角色会鼓励和激励人们。另一方面,还必须有像中药一样的建筑,它的效果会随着时间的推移而显现出来,不会对任何身体或心理状况产生过度压力或负担;它是安静的。。

阿尔托的住宅面积不大,体现了高效可持续性的模式,并因此降低了日常能源消耗。这座住宅是否反映了您对于如何建造家庭空间的看法呢?

我认为建筑的大小与人们之间距离的概念密切相关。阿尔托自宅的尺寸是他对于个体间适当距离概念的一个很好的例子。此外,阿尔托不仅有设计建筑内部的能力,还能仔细考虑并创建居住者之间的适当距离,无论是在建筑内部还是周围社区。

例如,玛丽娅别墅是一座大型住宅;然而,在设计时,它的设计着眼于许多人聚集在一个地方时发生的社会动态,以及在该地区田园诗般的氛围中如何保持人与人之间的适当距离。

他并不仅仅考虑数值尺寸,例如平方米,而是将建筑概念化为衡量个体之间、人与自然之间、人造和自然世界之间距离的一种手段。我认为,在这方面阿尔托有着非常精致的平衡感。

合适尺寸的感觉是主观的还是客观的?

这方面的一个例子是京都的一个町屋,门楣非常低,身高约175厘米的人必须弯腰才能进入,这可能对所有体型的个体都不舒适。然而,身高超过180厘米的人也不一定会感到不舒服或不自在。这是因为该空间体现了创造者的真诚和诚实,以及他们的文化模式和尺寸系统。这种氛围在整个城市中都能感受到。我相信,人们可以立即感觉到建筑或其内部的大小适合特定城镇或地区的语境、传统和文化,同时感受到周围区域的规模、道路的宽度和相邻房屋之间的距离感。人类有一定的接受能力来理解陌生的规模或尺寸。

重要的不是180厘米的门高是否具有国际性或普遍性,而是一个具体建筑的氛围和尺度是否与地区、气候、历史和其他相关因素的尺度和氛围相符。如果我们去参观一位阿拉伯石油大亨的住宅,尽管尺寸和尺度不熟悉,但我们很可能会感觉到建造它的人是真诚的,并遵循了从该地区的文化和习俗中得出的尺度感。

与其强求一些东西,不如让自己被这些流动所引导,从超越自己创造的东西中学习。这种谦逊是很重要的。

从一个日本建筑师的角度来看,你对现代西方文化有什么印象和见解?

我认为,一神论和多神论国家的思维方式存在显著的差异。这不是哪种方式更好或更差;这些只是不同的思维方式,影响到人们如何看待自己,以及如何与周围环境建立关系。

我就不能用一神论的方式思考。它已经在我的身体里根深蒂固,在与自然、朋友或任何地方的互动中,有各种存在看护我或支持我。对我来说,几乎不可能摆脱这种思维方式。

我觉得芬兰是一个传统上与我们的东方意识相通的国家。有一种信仰认为自然界中有多种精灵,例如在布里格曼的复活教堂或西伦的奥塔尼米教堂中可以看到这种信仰。庆祝森林中也有神灵存在的感觉让我感到非常平静;当我在西方遇到这种事情时,我会感到欣喜。

这对我们如何思考时间有一定影响。我认为时间有两种主要的流动方式。第一种是线性的,科技不断发展,社会不断进步。第二种是循环的,类似于太阳的升起和落下,没有进步或演化。简而言之,从事科学工作的人倾向于认同历史性的进步轨迹,即技术和人类的智慧在不断提高。例如,十年前的苹果手机功能不如现在的型号。相反,从事人类研究的人不认为莫扎特创作的音乐或者两百多年前陀思妥耶夫斯基所写的文学作品不如当代创作。

我认为我们目前正处于一个西方个体开始质疑线性时间应用于生活各个方面的时代。我希望西方能开始接受时间的周期性概念,让这个世界成为一个人们可以相互连接和共鸣的地方,而不受其国籍或种族的影响。

我特意使用了 "东方 "和 "西方 "这两个词,但如果不使用这样的代名词,说 "线性 "或 "周期性 "会更准确。

虽然你表达了对多神论和芬兰建筑的共情,但你的作品似乎具有强烈的西方几何学严谨性。为什么会这样?

我在美国看到的最东方的建筑是金伯尔美术馆。我感到它比我参观过的任何其他建筑都更具有东方建筑的特点。金伯尔美术馆是一个组织和秩序的领域,但这种秩序或几何形式并不是进化的,而是旋转或循环的;去了某处又回来了。我感到它具有难以想象的深度。

曼陀罗代表循环,但它也使用非常严格的几何学。通过使用其独特的节奏、韵律和几何学中的重复,有一种循环的感觉。我对这种东西非常感兴趣。

我认为它并不简单;相反,它非常复杂,有各种矛盾的元素并存。曼陀罗和金伯尔美术馆以三维或四维的方式表现了这种复杂性,并证明了几何学的严谨性并不一定与周期性世界相冲突。虽然康的建筑有以圆锥线为基础构造的拱顶,曼陀罗是一个圆圈,但我想强调的是,这并不仅仅是在平面或截面中使用圆形。

好的建筑不仅仅是一个词可以描述的。用语言来表达四维循环世界非常困难。我认为只有亲身体验才能理解。设计师的思想也会来回反复,回归原点,并穿越许多不必要的东西。我认为深度就是这样建立起来的,它是复杂的非线性思维的结果。

关于它与环境的关系,玛丽娅别墅采用了L形的结构,围绕着一个庭院,类似于阿尔托的自宅。在您的书《感性思考建筑》中,你建议将庭院朝南打开会更合适,因为它顺着阳光的路径。但是,他没有将房子朝向太阳方向,而是在相反的方向上创造了一个庭院,以更受保护的方式与自然互动。是什么促使阿尔托优先考虑背弃周围的自然?

我认为,阿尔托的建筑之所以难以用简单的语言表达并解释,正是因为他的设计非常复杂而微妙。两种相互冲突的与自然互动的方式并存:一方面,人们意识到与自然的连续性,倾向于利用当地的自然特征;另一方面,人们需要创造一个避难所,让个人在面对自然的严酷时感到安全。最明显的例子是他的实验室住宅,它牢固地扎根于自然地面,但被高墙包围,以保护人们免受自然的侵害。我认为阿尔托在他的建筑中一直在深入思考这种复杂的自然与人类及其周围环境之间的关系。

无论如何,芬兰非常寒冷,不受欢迎的动物也在游荡,所以当然需要考虑阻隔自然的重要性。

站在阿尔托的住宅前,人们注意到面向街道的外墙上没有太多开口。从这个角度看,黑白色的外墙可能会给人一种不受欢迎和难以穿透的印象。

是的,但我们不要忽视周边没有墙,这与日本不同。道路两旁和邻近房产的边界都没有墙;只有像农场一样的原木栅栏,反映了芬兰土地的连续性。

如今尤其是在日本,人们似乎非常渴望拥有土地和住房。他们经常过度表达从这里到那里的区域是他们的所有物。我认为这是对土地和空间稀缺性的一种反应。

然而,无论我们相信或感觉如何,个人永远不可能拥有100%的土地。吹过那里的风属于所有人,照耀那里的阳光也属于所有人。那里的土壤也与邻近地块的所有边缘相连。划定界限并不容易。在地下或地上,当你超过一定距离时,它就不再被认为是任何人的所有物。阿尔托没有创造独占性的房屋或社区,他非常注重土地的连续性。我认为这在他的自宅中非常明显。

你告诉我,"只有那些感情指向未来、想象力丰富的人,才能看到光线照射在空白、抽象的墙壁上的美感。" 为什么阿尔托在他自己的房子里打破了现代主义的抽象美学规则呢?

我认为现代主义在很大程度上根植于建筑师设计为中心的理念,并坚持一种人类无懈可击的观念。人类有一种傲慢,认为如果设计出了一个理想的城市或社会的理想蓝图,它将完全按照其意图实现。这种傲慢,在现在被认为是自负的,他们认为设计者可以从神的角度控制一切,并且有可能在世界任何地方建造类似风格的房屋和建筑。

我认为他们对人类的力量拥有极大的信心。然而,即使建筑和当时的背景基于这种人类力量的构建,人们也会衰老,某一时刻失去健康、力量和财富。人总会有失去一切的时候。

从这个角度来看,我觉得芬兰的气候让人不得不面对人类的脆弱性。那里非常寒冷,阳光很少。在这样一个严酷的环境中,我们被迫面对自己身体和精神上的脆弱性,往往仅仅因为身处其中而变得沮丧。这种挣扎在某种程度上是内在的。我感觉芬兰的建筑和文化源于这种情况,我对此深受共鸣。这可能是芬兰建筑高质量的原因,它在顺境和逆境中都能拥抱身体和灵魂。

一个国家有时是有活力的,有时是没有活力的。当一个社会失去活力时,那些在信仰和希望时期创造的东西会显得疯狂甚至可怕。

在你过去的一篇文章中,我记得你感叹现代运动对黑暗的根除,造成了平坦和平庸的空间。阿尔托的住宅是现代主义运动中迷恋整洁、卫生和健康的一部分。你能告诉我这个住宅里还有多少阴影或模糊性吗?在建筑内部它们还可以在哪里被发现?

我刚才提到了现代主义的问题;但是,我也相信现代主义开辟了很多可能性,可以用非常积极的方式来使用。在阿尔托的作品中,它们得到了研究并带来了很多益处。举个例子,大玻璃板是现代主义的产物——在芬兰,由于它们能使大量的阳光和热量进入建筑物,具体来说,在冬季证明是有益的。我觉得有趣的是,在细节中,现代主义的发明很好地融合了手工制作的温暖、天然材料的应用和功能的高性能。

我认为,在阿尔托的作品中,黑暗或神秘的存在体现在桑拿房中。阿尔托的许多住宅都有桑拿房,它们的形式非常传统。这些都是本土的、黑暗的、神秘的地方,脱离了现代主义的精神。

阿尔托的自宅有一个独特的特点,使其有别于其他住宅,它既是一个生活空间,又是一个办公室。位于房子一楼的起居室,经常被用来进行办公会议。你是如何设想住宅空间与工作区域的互动的?

我选择阿尔托的自宅,是因为我被他的公平感所吸引。阿尔托的设计理念是一致的,不管是他自己的住宅还是别人的。许多建筑师在为别人设计高度实验性的住宅的同时,却保持自己的住宅较为保守,但阿尔托没有这样做。我觉得,他一定有一种自由主义和公平的意识。这种态度可能出现在家庭和工作空间的融合上。

我认为阿尔瓦-阿尔托相信以住房原则设计所有类型的建筑物;即工作场所也应该是一个家,一个人类居住的巢穴,是人们归属的地方。无论是教堂、音乐厅、大学还是村委会,所有这些建筑的起点都是一个温暖地欢迎人的身心的家。我相信,阿尔托一定明白,在恶劣的环境中,人的存在、温暖和工艺等方面的意义和价值。在现代主义中,人们常常强调工业化或大规模生产的功效;然而,我相信,在理解这些发明的重要性的同时,阿尔托也开发了细节、施工方法和规划,以唤起人类的温暖感。

至于家庭和工作空间的融合,我认为这与人们不能孤单生活的事实有关。人是一种群居动物,当他们聚集在一起时,会变得更加温暖。在人口密度较低的芬兰,无法感受到他人的存在可能是相当可怕的。

在他家的一个屋檐下,每个人都有一个地方可以做一些事情:包饺子、读书、画建筑图,感受他人的存在。我认为,当时的芬兰社会比我们今天更宽容,更愿意分享空间。

住宅的氛围和使用与办公室的结合,并不完全是阿尔托的个性使然。我相信,他的妻子艾诺的存在在当时也是非常重要的。阿尔托似乎有性别平等的意识,他相信女性可以像男性一样在社会和建筑业中取得进展。这是阿尔托的另一个特点。当你参观那座住宅时,你可以看到他社会进步的观点。它真正告诉我们阿尔托的人道主义公平。

2022年12月29日

堀部安嗣: 私の師匠である益子義弘先生が、アアルトのことが好きで、君もぜひフィンランドに行って、アアルトの作品を見るといいよ、と言ってくださったのがきっかけです。実は、当時はアアルト自邸を見ても今ほどピンときませんでした。なんだ普通の家じゃないか、という感じで、そこまで刺激がなかったことを覚えています。ただ、フィンランドの風土や、日本人に近くシャイで温厚な性格のフィンランド人との触れ合いを通じて、フィンランドに対してのシンパシーみたいなものを、非常に強く感じ、また行きたいという風に思いました。その後、フィンランドには都合4、5回は行っていると思います。最近は、アアルトの作品、特に自邸に対しての素晴らしさを強く感じるようになってきました。これは自分の経験や年齢、あるいは、建築に対する理解みたいなものが深まってきたからなのではないかと思います。

あるテキストの中で、興味深い説話を引用されていたと思います(「建築への憧れと絶望」『JA 90』2013) 皇帝が宮廷画家に「描くのが難しいものは何か」と尋ねると、宮廷画家は「鬼を描くのは簡単だが、犬は難しい」と答えた。見慣れたものに対して私たちは、すぐに間違いに気づいてしまうからだ、と。それは、建築に対しても同じことだとおっしゃっていますが、アアルト自邸は、犬的なものなのでしょうか?それとも鬼的なものなのでしょうか?

時間の経過によっても変わるものだと思いますが、おそらく建った当初は、かなり鬼的な要素があったと思います。けれども、時代や社会の変化、それに建築の技術や文化の変化を経て、年々、犬的な側面が強くなってきたのではないかと思います。

いい建築には、そういう変化があるように思います。当時は、非常にラディカルで過激だったものが、今となってみれば、とても穏やかで、表現が丸くなっているということがよくあります。アアルト自邸が犬的な側面を持ち始めたのも、等身大の人間の心身のことを、アアルトが理解していたからだと思います。

人間の心身への正直さみたいなものを外した鬼的な表現というのは、やはり長く保たないもので、人から飽きられてしまう性格のものになるのではないかと思います。

建築には大きく分けると、二つの役割があると思います。一つは花火のような役割で、花火を打ち上げて人々を鼓舞したり、奮い立たせたりして、元気を煽っていくような、お祭り的な役割というのも当然あると思います。一方で、漢方薬のような時間と共に効能が現れてくるような、地味だとしてもどんな心身の状態にも無理や負担のない、そういった建築の役割も必要だと思います。最も美しいものだと私は思っていますから。

アアルト自邸は、サイズが控えめで日々のエネルギー消費も少なく、サスティナビリティという点において非常に良いモデルになるのではないかと思います。こういった住宅がやはり、生活空間としては適切であるとお考えでしょうか?

建築のサイズ感というのは、人と人との距離感のことだと思います。そして、アアルト自邸のサイズというのは、彼の考える人と人との距離感の適切な解であったのだと思います。また、彼は建物内部のことだけではなく、隣人や地域の中での距離感といった複合的な内外の人との距離の調整やデザインが、非常に達者だったのではないかと思います。

例えば、マイレア邸は非常に大きな住宅ですが、そこに大勢の人が集まった時のことも考えていたのだと思いますし、あの地域の牧歌的な風土や雰囲気の中での、人と人との適切な距離感を考え、あのサイズ感になっているのだと思います。

つまり、何平米だとか数値的な広さというよりも、人と人との距離感、自然との距離感、そして、人工と自然との距離感を測る役割として、建築を考えていたのだと思います。アアルトは、その辺のバランス感覚が非常に長けているのだと思います。

適切なサイズ感というものは、主観的なものなのでしょうか?それとも客観的なものなのでしょうか?

例えば、京都の町家は、鴨居も非常に低くて、身長が175センチぐらいある人は、必ず頭をかがめないといけなかったりしますし、必ずしもどんな体型の人にも快適かと言えば、そうではないと思います。けれども、おそらく身長が180センチ以上の人がそこに行っても、意地悪を感じたり、居心地の悪さを感じるかというと、そんな事もないと思います。それは、その文化や寸法体系を作った人々の、誠実さや正直さが、空間に表れているからだと思います。そういったものは、街全体から感じられるものです。周囲のスケール感であったり、道路の広さであったり、隣の家との間隔みたいなものを相対的に体の中で感じとって、この街、あるいは、ここでの伝統や文化の中では、このスケールがちょうどいいことなんだということを、瞬時に感じ取れる力が人間にはあるのではないかと思います。それが、馴染みのないスケール感やサイズ感であったとしても理解できるような、ある種の感受性があるのでしょう。

大事なことは、ドアの高さが180センチしかないことが国際的ではないとか、ユニバーサルではないとかそういうことではなく、地域であったり、風土であったり、歴史であったり、そういったもののもつスケール感や雰囲気と、具体的な一つの建物の内部の雰囲気やスケール感がフィットしているということなのではないでしょうか。例えば、逆に私たち日本人が、アラブの石油王の家に行ったとします。それが体験したことのない寸法や、スケール感であったとしても、ここを作った人たちは誠実に、ここでの文化や慣習の中から、このスケール感を導き出していることを、私たちは感じることができるのだと思います。

ですから、そこに何かを無理やりクリエーションするよりも、それらの流れに身を任せ、一個人のクリエーションを超えた何かに教わっていく。そういった謙虚さが大事じゃないかなと思います。

日本の建築家として、現代の西洋の文化に対する印象や、お考えを教えていただけますでしょうか?

一神教の国と多神教の国、その考え方の違いというのは、非常に大きいなと思います。どっちが良い悪いということではなく、単に自分自身や周囲との関わり方への違いがあるのだと思います。

私は一つの神を信じている人間ではなく、どんなところにも何か自分を見守ってくれる存在がいたりだとか、自分を支えてくれるものが自然界の中にあったり、友人の中にあったり、さまざまなところに存在しているという、そういう考え方からどうしても抜け出せないところがあります。それはもう身体にもすり込まれてる、という感じでしょうか。

一方で、フィンランドというのは、我々とその辺の感覚が似ていて、自然の中にも、いくつも精霊が宿っているという考えがあると思います。典型的なのが、ブリュックマンの教会や、オタニエミのシレンの教会でしょうか。ああいう森の中に神様がいる、というような感覚に出会うと、非常に心が穏やかになるというか。西洋の中にある、ああいうものに触れると喜びを感じますね。

時間に関しての考え方の違いもあるのだと思います。私は、大きく分けると二つの時間の流れ方があると思っています。一つは、一直線に進んでいく時間の流れ方。どんどん技術は進化して、良くなっていくという時間の流れ方です。もう一つは、ぐるぐると循環した流れ方。太陽が昇って、また沈んでいくような、進化もしていなければ、進歩もしていないという循環的な流れ方です。大きく言うと、理系の人は、技術はどんどん進化して、人間はどんどん賢くなるといった進歩史観を持っているのだと思います。例えば、10年前のiPhoneは今と比べると使いものにならないですよね。一方、文系の人は、200年以上前のモーツァルトの曲や、ドストエフスキーの書いたものが今よりも劣っているとは考えません。

今は、西洋の方々も、そういった一直線に流れる時間に対して、大きな疑問を感じてきている時代なのではないかと思います。人間は、別に進歩も進化もしていないというような循環した時間の流れ方に、西洋の方々も気づき、国籍や人種を超えて共鳴し合う世界へとなっていくといいなという風に思っています。

あえて、東洋とか西洋という代名詞を使って説明していますが、そういった代名詞を使わずに、直線型なのか、循環型なのかという言い方をした方が的確ですね。

多神教やフィンランドの建築に共感を示されている一方で、あなたの作品には、西洋的な強い幾何学の厳密性を感じます。それはなぜでしょうか?

実は、アメリカに行って一番東洋的だなと思ったのは、キンベル美術館でした。他のどんな建築よりも、遥かに東洋的な建築だという風に感じました。キンベル美術館は、まさに整理整頓、秩序の世界ではあるのですが、その秩序というか幾何学というものが、先ほど述べたように、進化的なものではなく、回転していくというか、循環していくというか、またどこかに行ってまた戻ってくるというか、そういった奥行きと深さを持っているように思いました。

例えば、循環を表している絵には曼荼羅がありますが、曼荼羅にも非常に厳格な幾何学が用いられていて、テンポやリズムの中に円を意識していくというか、幾何学の中に丸を意識していくというような感じがあります。そういうところに、私は非常に興味があります。

複雑なのだと思います。シンプルではない。非常に複雑でいろいろな複合的なものが絡み合って、さまざまなアンビバレンツなものが同居しているというか。それを三次元的、あるいは四次元的に表しているのが曼荼羅であり、キンベル美術館ではないかなと思います。厳密な幾何学が循環的な世界と相反するものであるかというと、必ずしもそうではないと思います。つまり、キンベル美術館には、サイクロイド曲線がありますし、曼荼羅にも円の形がありますが、平面や断面でそういった形を使うことが重要なのではないと思います。

本当に一言では言えないですよね。良い建築って。四次元的に循環している、あの世界を言葉で表すというのは難しく、体感する以外ないのだと思います。設計者の考えも本当に行ったり来たりしながら、元に戻ったり、無駄がいっぱいあったりするのですが、そういった複雑な思考を続けたからこそ、あの奥深さがあるのではないかなと思います。直線型の思考からは出てこない複雑さだと思います。

自然との関係に関して言えば、マイレア邸もアアルト自邸と同じように、L字型のボリュームが中庭を囲んでいます。あなたは著書『建築を気持ちで考える』の中で、マイレア邸の中庭は、方角に従って素直に南側に向けて配置した方が良かったのではないか、とおっしゃっていますが、実際は、太陽の方角に反して、アプローチのある南側と逆方向に中庭を開き、自然との関係を作ろうとしています。アアルトが太陽の方角よりも、周囲の自然から背を向けることを優先した理由は何なのでしょうか?

アアルトの建築がなかなか言葉にしづらく、そして単純な言葉では語れない理由は、まさにその複雑さと繊細さにあるのだと思います。自然に対しての連続性を意識したり、風土を生かそうという気持ちがある一方で、自然の厳しさに対して、人の安心できる居場所を作らなければいけない、という相反する自然への向き合い方みたいなものが共存しているからだと思います。一番わかりやすいのは、ユヴァスキュラの夏の家ですね。自然の大地にしっかりと根を下ろしながらも、高い壁を建てて自然をフレーミングしたりして、自然から身を守るような設えをしています。そういった複雑な自然への向き合い方や、人間と自然との微妙な関係性を、アアルトは深く考え続けていたのではないかと思います。

フィンランドは、とにかく寒いですし、歓迎されない動物も入ってきたりしますから、自然を遮断することの重要性というのは、あの風土においては当然考えなければいけないことなのだろうと思います。

アアルト自邸の前に立つと、道路側のファサードには開口部が少ないことに気づきます。黒と白の外観は、無表情で自閉的なものにも見えますが、その点についてはどうお考えでしょうか?

とはいえ、道路沿いや隣地境界には、日本のような塀がないことがわかると思います。隣地境界には、塀の代わりに、牧場の丸太の柵のようなものがあるだけなのですが、何かフィンランドの大地の連続性みたいなものが意識されているのではないでしょうか。

今日の、特に日本では、土地や住まいに対する所有への欲望というものが、とても強いように思います。ここからここは自分の持ち物だ、というようなことが過激に表現されているのですが、それは逆に、それだけ土地に余裕がないことの表れなのだと感じます。

ところが、その土地をその人が100%所有しているのかというと、もちろんそうではなく、そこに入ってくる風はみんなのものですし、そこに降り注ぐ太陽もみんなのものです。そこの土も、隣の家からずっと繋がってきているものですので、そこに線を引くということはなかなかできないわけです。地下や上空も、ある距離を超えると、もはや所有物ではなくなりますよね。アアルトは自分だけが独占するような、町や家を作るのではなく、やはり大地の連続性というものをとても意識していたのではないかと思います。それは、あの自邸にもすごく表れているように思います。

「真っ白い抽象的な壁に当たる光を見て美しいと思えるのは、気持ちが未来に向いている人や想像力が豊かな人だけなのです。」(『建築を気持ちで考える』TOTO出版 2017年)とおっしゃっていましたが、アアルトはなぜそうしたモダニズムの抽象的な美学を自邸において表現しなかったのでしょうか?

モダニズムというのは人間、あるいは建築家の設計主義的な理想像を強く掲げることで、人間の無謬性みたいなものを信じていたのだと思います。例えば、理想の設計図を描いて、理想の都市像や社会みたいなものを描けば、その通りに実現していくというような、どこか人間の驕りのようなものがあったように思います。設計者が神の視点に立って全てをコントロールすることができ、世界中どこにでも同じスタイルで住宅や建築が可能であるという、今となってみれば驕りとしか思えないようなことが繰り広げられていたのだと思います。

つまり、人間の強さみたいなものを非常に信じていたんだと思います。ところが、その人間の強さみたいなものを基準として、建築やその時代の背景を作ったとしても、人間というのは老いていくもので、元気なときばかりではなく、権力を失うときもあれば、お金がなくなるときもある。そういうときが必ず来ますよね。いいときばかりではない。

フィンランドは、そういった観点から見ると、人間は弱いものであるということを自覚できる風土なのではないかと思います。つまり、非常に寒い。それから晴れる日が少ない。そんな過酷な環境の中では、ただそこにいるだけで憂鬱になっていくような人間の弱さに対して、肉体的にも精神的にも向き合わざるを得ないわけです。そういう環境への葛藤が本質的にあるのだと思います。フィンランドの建築や文化は、そういった状況から出てきているものだと思いますし、私はそういうところに非常に共感します。そのことが、元気な時も病めるときも、心身を包み込んでくれるようなフィンランドの建築の質の高さにつながっていったのではないかなと思います。

やはり国も元気なときもあれば、そうでないときもあります。社会に元気がなくなってきたときに、自信や希望に満ち溢れていた時代に作られたものというのは、どこか狂気に感じられたり、怖いものになっていくのだと思います。

あるテキストの中で「街や建築が闇を嫌い、異常なまでにフラットで清潔になってしまった」ということを書かれていたと思います (「人に寄り添うかたち」『JA 90』2013) アアルト自邸はまさに、清潔さや衛生面、それに健康といったことに取り憑かれていたモダンムーブメントの渦中にあった住宅ですが、そこに陰りや曖昧さのようなものは、感じられるのでしょうか? また、どの部分にそういった性質が残っているとお考えでしょうか?

モダニズムの問題みたいなことに触れましたが、モダニズムが切り開いたポジティブな側面もたくさんあると思います。それは、アアルトの仕事の中にも非常に良い形で表れていると思います。例えば、大きなガラスは、モダニズムの産物ですが、フィンランドでは特に、冬に太陽の日差しや熱をたっぷりと取り入れるために非常に有効なものだと思います。そういったモダニズムの性能の高さと、ディテールにおける手仕事のあたたかさや、自然素材の使い方とが良い形で融合しているというところには魅力を感じますね。

そして、アアルトにおける暗がり、あるいは神秘性というものは、サウナに表れているのではないかと思います。多くのアアルトの住宅にはサウナがあり、それらは非常にトラディショナルな形をしています。そこはモダニズムの精神から切り離された、土着的で暗がりをもった神秘性のある場所になっていると思います。

アアルト自邸は、家でもあり仕事場でもあるという、他の住宅とは決定的に異なる特徴があります。一階のリビングは、仕事のミーティングでも頻繁に使われていたようですが、こういった仕事場と生活空間の関係性については、どうお考えでしょうか?

この自邸を選んだ理由は、アアルトのフェアさみたいなものに惹かれたからです。アアルトの態度には、それが自邸であるとか、他人の家であるとかといった違いを感じません。他人には非常に実験的な家を作る一方で、自分の家は保守的であるという建築家も数多くいますが、アアルトはそうではない。そのリベラルさというか、人間的なフェアさみたいなものを非常に強く感じます。そのことは、職住が一体になっているということにも繋がるのだと思います。

アアルトは住宅を基本に考えていて、仕事場も住宅であり、そこが人間の巣であり、人間の居場所であると考えていたのではないかなと思います。それが教会であっても、ホールであっても、大学であっても、それに村役場であっても、多くの人の心身を温かく受け入れてくれる住宅というものが、考えの起点になっているのだと思います。人の気配や、ぬくもり、あるいは手仕事みたいなものが、ああいう厳しい風土の中では、どれだけ貴重なものなのかを、アアルト自身よくわかっていたのだと思います。モダニズムは工業化や、量産化の有用性から語られることが多いですが、アアルトは、そういったものを大事にしながらも、人のぬくもりを感じさせるディテールや構法、それからプランニングをしていったのではないかと思います。

人は、一人では生きていけないということとも関係しているのだと思います。人も群れをなす動物の一種ですので、みんなで集まれば、それだけ温かくもなります。それに、人の気配が感じられないということは、人口密度の低いフィンランドにおいては、非常に怖いことなのではないかなと思います。

建物の一つ屋根の下では、人の気配を感じながら、みんなで本を読んだり、図面を引いたり、何か押しくら饅頭をしているような状態でいる。当時のフィンランドは、そういったことに関して、いまの我々以上に許容できた社会であったのかなと思います。

あの住宅の雰囲気、そして事務所を併用しているということに関しては、アアルトだけの性格からくるものではなく、当時の奥さんであるアイノの存在というものも非常に大きいと思います。当時からアアルトは男女の平等、つまり女性も社会に進出して、男性と何ら変わらなく建築の仕事ができるという、そういうことへの理解があったんだと思います。そこにも、アアルトの特徴がみてとれます。アアルトが社会的にも先進的な眼差しを持っていたということが、あの自邸に行くとよく伝わってきます。人間的なフェアさに対する眼差しですね。

2022年12月29日

Yasushi Horibe: My teacher, Yoshihiro Masuko, held a great admiration for Aalto and told me to travel to Finland to see his works. To be honest, upon my initial visit, I was not particularly impressed with Aalto’s own house; I remember thinking, “It’s just an average house.” However, the natural features of Finland and the interaction with the reserved and gentle Finnish people – akin to the Japanese – evoked a deep sense of personal empathy towards Finland. Since then, I have returned to the country on four or five occasions and recently, come to appreciate Aalto’s work, particularly his own house. I attribute this to my experiences, my age, and my growing understanding of architecture.

IN YOUR TEXT (“MY ADMIRATION AND DESPAIR FOR ARCHITECTURE IN JA 90/2013”), YOU NOTED AN INTERESTING ANECDOTE: A KING ASKING A PAINTER WHAT WAS THE MOST DIFFICULT THING TO PAINT. THE PAINTER REPLIED THAT IT WAS EASY TO PAINT A DEMON BUT NOT A DOG—WE WOULD IMMEDIATELY RECOGNISE MISTAKES IN THE REPRESENTATIONS OF WHAT WE KNOW VERY WELL. YOU ALLUDE TO ARCHITECTURE, SAYING THAT DESIGNING A CALM-LOOKING BUILDING IS LIKE PAINTING A DOG. IS ALVAR AALTO’S HOUSE MORE LIKE A DOG OR RATHER LIKE A DEMON?

I think it has changed over time. Probably, when it was initially constructed, there was a very demon-like appearance to it. However, due to changes in both social and architectural techniques and culture, I think the dog-like aspect became more prominent.

In many cases of good architecture, this process usually happens; what once was very radical and avant-garde soon becomes soft and more relaxed in expression. An important factor in Aalto’s house becoming dog-like with time is that Aalto understood a life-size person’s body and mind.

If the expression is demon-like and insincere to the human body and mind, it will not last long, and people will become fatigued with it.

Generally speaking, I think architecture has two primary roles. One is like launching fireworks, which raises people’s spirits; a celebratory role of architecture that encourages and inspires. On the other hand, there must also be architecture like Chinese herbal medicine, which shows its effects over time and which is not overpowering or burdensome to any physical or mental condition; it is quiet.

AALTO’S RESIDENCE IS MODEST IN ITS SIZE, EMBODYING A MODEL OF HIGHLY EFFICIENT SUSTAINABILITY, AND CONSEQUENTLY LOWER DAILY ENERGY EXPENDITURE. DOES THIS HOUSE REFLECT YOUR VIEWS ON HOW DOMESTIC SPACES SHOULD BE BUILT?

I think that the size of architecture is intimately tied to the concept of distance from others. The dimensions of Aalto’s own house are a fitting example of his ideas about the appropriate distance between individuals. Furthermore, Aalto had a keen ability to not only design the interiors of buildings but also carefully consider and create appropriate distances between the inhabitants, whether they be within the building or in the surrounding community.

For example, the Villa Mairea is a large house; however, it was designed with an eye to the social dynamics that occur when many people congregate in one place, and how the distance between people should be maintained in the idyllic atmosphere of the area.

Rather than considering only numerical measurements, such as square meters, he conceptualized architecture as a means of measuring the distance between individuals, between people and nature, and between the man-made and natural world. I think Aalto had a very refined sense of balance in that regard.

IS THE FEELING OF A SUITABLE SIZE SUBJECTIVE OR OBJECTIVE?

An example of this is a machiya townhouse in Kyoto, where the lintel is so low that a person of about 175 cm in height must bend to enter, which may not be comfortable for individuals of all body types. However, it is not necessarily true that those taller than 180 cm would feel uncomfortable or ill-at-ease. This is because the space embodies the sincerity and honesty of those who created it, along with their cultural patterns and systems of sizes. This atmosphere can be sensed throughout the entire city. I believe that humans can instantly sense that the size of the building or its interior is appropriate for the context, tradition, and culture of that particular town or area, while feeling the scale of surrounding area, the width of roads, and the sense of distance between neighbouring houses. Humans have a certain receptivity to understand unfamiliar scale or size.

What is important is not whether the door height of 180 cm is international or universal, but rather, whether the atmosphere and scale of a specific building align with the scale and atmosphere of the region, climate, history, and other relevant factors. If we were to visit the house of an Arab oil tycoon, despite the unfamiliar dimensions and scale, we would likely sense that the people who built it were sincere and followed the sense of scale derived from the culture and customs of the region.

Instead of forcing something, it is better to let oneself be guided by those flows and learn from something beyond one’s creation. This kind of humility is important.

FROM THE VIEWPOINT OF A JAPANESE ARCHITECT, WHAT ARE YOUR IMPRESSIONS AND INSIGHTS ON MODERN WESTERN CULTURE?

I believe that there is a significant difference between the ways of thinking prevalent in monotheistic and polytheistic countries. It is not about which one is better or worse; these are simply different ways of thinking that affect how people view themselves and how they build relationships with their surroundings.

I just can’t think in a monotheistic way. It has already been ingrained in my body that there are various existences that watch over me or support me in the interaction with nature, friends, or in any place. For me, it is almost impossible to get over this way of thinking.

I feel that Finland is a country that traditionally shares our Eastern sense. There is a belief that there are multiple spirits in nature, and examples of this can be seen in Bryggman’s Resurrection Chapel or Siren’s Otaniemi Chapel. Celebrating the feeling that there is also a god in the forest makes me feel very calm; I find joy when I come across such things in the West.

It has a certain impact on how we think of time. I believe there are two primary ways in which time flows. The first is linear, with technology continually advancing and society progressing. The second is cyclical, akin to the rising and setting of the sun, with no progression or evolution. To simplify, people working in sciences tend to subscribe to the idea of a historical trajectory of progress, wherein technology and human intelligence are constantly improving. For instance, an iPhone from 10 years ago is not as functional as the present-day models. Conversely, people in human studies do not believe that a piece of music composed by Mozart or a literary work written by Dostoevsky over 200 years ago is inferior to contemporary creations.

I believe that we are currently in an era where individuals in the West are beginning to question this linear manner of time applied to all aspects of life. I hope that the West will begin to embrace the cyclical idea of time and that the world will become a place where individuals can connect and resonate with one another regardless of their nationalities or races.

I am using the terms “East” and “West” deliberately, but it would be more accurate to say “linear” or “cyclical” without using such pronouns.

WHILE EXPRESSING SYMPATHY FOR POLYTHEISM AND FINNISH ARCHITECTURE, YOUR WORKS SEEM TO HAVE STRONG WESTERN RIGOUR OF GEOMETRY. WHY IS THAT?

The most Eastern thing I saw in America was the Kimbell Art Museum. I felt that it was a far more Eastern building than any other building I had visited. The Kimbell Art Museum is a realm of organisation and order, but that order or geometry is not evolutionary, but rather rotational or cyclical; going somewhere and coming back again. I felt that it had an incredible profundity.

A mandala represents circularity, but it also uses very strict geometry. There is a sense of circulation by using its unique tempo, rhythm, and repetition within the geometry. I am very interested in that kind of thing.

I think it is not simple; rather, it is very complex, with various ambivalent elements coexisting. The mandala and the Kimbell Art Museum represent this complexity in a three or four dimensional way, and prove that geometric rigour is not necessarily in conflict with the cyclical world. Although Khan’s building has vaults constructed on cycloids, and a mandala is a circle, I would like to emphasise that this is not about merely using circles in plans or sections.

Good architecture cannot be described in just one word. It is really difficult to express the four-dimensional cyclical world using words. I think it can only be experienced. The designer’s thoughts also go back and forth, return to the origin, and traverse through many unnecessary things. I think that this is how depth is built up; it is a result of complex non-linear thinking.

CONCERNING ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ENVIRONMENT, VILLA MAIREA HAS AN L-SHAPED STRUCTURE THAT ENCLOSES A COURTYARD, SIMILAR TO AALTO’S OWN HOUSE. IN YOUR BOOK „THINKING ABOUT ARCHITECTURE WITH FEELING” YOU SUGGEST THAT HAVING THE COURTYARD OPENED TOWARDS THE SOUTH WOULD HAVE BEEN MORE APPROPRIATE AS IT FOLLOWS THE PATH OF SUNLIGHT. INSTEAD OF ORIENTING THE HOUSE TOWARDS THE DIRECTION OF THE SUN, HE CREATED A COURTYARD IN THE OPPOSITE DIRECTION OF THE APPROACH THAT ALLOWED HIM TO INTERACT WITH NATURE IN A MORE PROTECTED WAY. WHAT COULD HAVE MOTIVATED AALTO TO PRIORITISE TURNING HIS BACK ON SURROUNDING NATURE?

I think the very reason why Aalto’s architecture is hard to put into words and can’t be explained by simple words is because of the complexity and subtlety of his designs. Two conflicting ways of interacting with nature coexist: on one hand, there is an awareness of continuity with nature and an inclination to take advantage of the local natural features, and on the other hand, there is a need to create a sanctuary where individuals can feel secure in the face of nature’s harshness. The most conspicuous example is his experimental house, which is firmly rooted in the natural ground but encased by tall walls to protect people from nature. I think Aalto has continued to think deeply about such complex approaches to nature and the relationship between humans and their surroundings in his architecture.

In any case, Finland is cold and unwelcome animals roam, so the importance of blocking off nature is certainly something that needs to be considered.

STANDING IN FRONT OF AALTO’S HOUSE, ONE NOTICES THE ABSENCE OF MANY OPENINGS ON THE STREET-FACING FACADE. THE BLACK-AND-WHITE EXTERIOR MAY SEEM UNWELCOMING AND IMPENETRABLE FROM THIS ANGLE.

Yes, yet let’s not overlook the absence of walls on the perimeter unlike in Japan. There are no walls along the road or at the boundary of the neighbouring property; just a log fence like on a farm, reflecting Finnish land’s continuity.

Nowadays particularly in Japan, there seems to be a strong desire for possession of land and housing. People often excessively express that an area from here to there is their possession. I think this is a reaction to the scarcity of land and space.

However, whatever we believe or feel, it is never true that an individual owns 100% of the land. The wind that blows through there belongs to everyone, and the sun that shines on it also belongs to everyone. The soil there is also connected on all sides to the neighbouring plots. It is not easy to draw a line. Underground or above the ground, when you go beyond a certain distance, it is no longer considered owned by anyone. Aalto did not create houses or neighbourhoods that were exclusive, he was very conscious of the continuity of the land. I think this is very evident in his own house.

YOU TOLD ME THAT “ONLY THOSE WHOSE FEELINGS ARE DIRECTED TOWARD THE FUTURE AND WHOSE IMAGINATIONS ARE FERTILE CAN SEE THE BEAUTY IN THE LIGHT HITTING A BLANK, ABSTRACT WALL.” WHY DID AALTO BREAK THE RULES OF ABSTRACT AESTHETICS IN MODERNISM IN HIS OWN HOUSE?

I think modernism was heavily rooted in a design-centric ideal of architects, and adhered to a notion of human infallibility. There was a sort of human arrogance in assuming that if an ideal blueprint for an ideal city or society were devised, it would be realised exactly as it was intended. Such conceit, which would only nowadays be considered conceited, was the belief that the designer could control everything from a god-like perspective and that it was possible to construct houses and architecture in a similar style anywhere in the world.

I think they possessed great faith in the strength of human beings. However, even if architecture and the background of the time were created based on that kind of human strength, people age, at one point lose health, power and wealth. There will always come a time when one loses everything.

From this perspective, I feel that Finland has a climate where people come to terms with human vulnerability. It is very cold; there are very few sunny days. In such a harsh environment, we are forced to confront our vulnerability both physically and mentally, often becoming depressed just by being there. The struggle is somehow intrinsic. I sense that Finnish architecture and culture originated from such a situation and I empathise with it greatly. This is likely the reason for the high quality of Finnish architecture, which embraces body and soul in both good and bad times.

Sometimes a country is energetic, and sometimes it is not. When a society loses its energy, the things that were created during times of faith and hope can seem crazy or even terrifying.

IN ONE OF YOUR PAST WRITINGS, I RECALL YOU LAMENTED THE MODERN MOVEMENT’S ERADICATION OF DARKNESS, CAUSING FLAT AND BANAL SPACES. AALTO’S HOUSE IS A PART THE MODERN MOVEMENT ENTHRALLED BY NEATNESS, HYGIENE AND FITNESS. COULD YOU TELL ME HOW MUCH SHADOW OR AMBIGUITY IS PRESENT IN THIS RESIDENCE? WHERE CAN THEY STILL BE LOCATED WITHIN THE BUILDING?

I just mentioned the problems of modernism; however, I also believe that modernism opened up a lot of possibilities that could be used in a very positive way. In Aalto’s work, they are studied and bring many benefits. As an example, big glass panes are a product of modernity – and in Finland specifically, prove beneficial during the wintertime due to the significant amount of sunlight and heat they enable into buildings. I find it fascinating that there is a good fusion of the warmth of handwork, the use of natural materials, and the high performance in functionality by the invention of modernism in the details.

I think that the darkness, or the presence of mystery in Aalto’s work, is evident in the sauna. Many of Aalto’s houses have saunas, which are very traditional in form. These are indigenous, dark, and mystical places that are detached from the spirit of modernism.

AALTO’S RESIDENCE HAS A UNIQUE PECULIARITY THAT MAKES IT DISTINCT FROM OTHER HOMES—IT SERVES AS BOTH A LIVING SPACE AND AN OFFICE. THE LIVING ROOM, LOCATED ON THE FIRST FLOOR OF THE HOUSE, WAS FREQUENTLY USED FOR OFFICE MEETINGS. HOW DO YOU ENVISION RESIDENTIAL SPACES INTERACTING WITH WORK AREAS?

I chose Aalto’s own house due to my attraction to his sense of fairness. Aalto’s approach is consistent, no matter if it is his own house or someone else’s. Many architects create highly experimental houses for others while keeping their own houses conservative, but Aalto does not. I feel that he must have a sense of liberalism and fairness. This attitude probably appears in the the integration of home and work spaces.

I think that Alvar Aalto believed in designing all types of buildings based on the principles of housing; namely, that the workplace should also be a home, a nest for humans, and a place where people belong. Whether it is a church, a music hall, a university, or a village hall, the starting point for all of these is indeed a house, that warmly welcomes both the body and soul of people. I believe that Aalto must have understood the significance and value of aspects such as human presence, warmth, and craftsmanship in a harsh environment. In modernism, people often emphasise the efficacy of industrialisation or mass production; however, I believe that while understanding importance of such inventions, Aalto developed details, construction methods, and planning to evoke a sense of human warmth.

As for the integration of home and workspace, I believe it is related to the fact that people cannot live alone. People are a kind of herd animal, and when they gather together, they become warmer. In Finland, where population density is low, not being able to feel the presence of others can be quite frightening.

Under one roof of his house, there is a place for everyone to do something: make dumplings, read, draw architecture, and feel the presence of others. I think that at the time Finnish society was more tolerant and willing to share space more than we are today.

The atmosphere and use of the house in combination with the office are not solely the result of Aalto’s personality. I believe that the presence of his wife, Aino, was also very important at the time. It seems that Aalto had an understanding of gender equality; he believed that women could advance in society and work in architecture no differently than men. This is another example of Aalto’s feature. You can see his socially progressive perspective when you visit that house. It truly tells us about Aalto’s human fairness.

29.12.2022

堀部安嗣: 我的老师益子义弘非常钦佩阿尔托,并告诉我要去芬兰看他的作品。老实说,我初次拜访时,并没有对阿尔托的自宅特别印象深刻;我记得当时想,“这只是一个普通的住宅。” 但是,芬兰的自然风光以及与保守、温和的芬兰人(类似于日本人)的互动,唤起了我对芬兰的深刻共鸣。从那时起,我已经回到这个国家四五次,并最近开始欣赏阿尔托的作品,尤其是他的自宅。我把这归因于我的经历、年龄和对建筑学的逐渐理解。

在您的文章《建筑的敬佩和绝望》(JA 90/2013)中,您提到了一个有趣的轶事:一个国王问一个画家最难画的是什么。画家回答说,画恶魔很容易,但画狗却不容易——我们会立刻意识到熟悉的事物的表现错误。您提到了建筑,说设计一个看起来平静的建筑就像画一只狗。阿尔瓦客阿尔托的住宅更像一只狗,还是更像一个恶魔呢?

我认为随着时间的推移,它发生了变化。可能在最初建造时,它有一个非常像恶魔的外观。然而,由于社会文化和建筑技术的变化,我认为狗的一面变得更加突出了。

在许多优秀的建筑案例中,通常会发生这样的过程;曾经非常激进和前卫的东西很快就会变得柔和、更放松地表现出来。阿尔托的住宅在时间的推移中变得更加狗一般的重要因素之一是,阿尔托了解人的真实体验,包括身体和心灵的体验。

如果建筑的表达方式像恶魔一样不真诚并且与人类身体和心灵的体验相矛盾,它不会持续太久,人们会对其感到疲劳。

一般来说,我认为建筑有两个主要的作用。一种像烟花一样,能够提升人们的精神;建筑的庆祝角色会鼓励和激励人们。另一方面,还必须有像中药一样的建筑,它的效果会随着时间的推移而显现出来,不会对任何身体或心理状况产生过度压力或负担;它是安静的。。

阿尔托的住宅面积不大,体现了高效可持续性的模式,并因此降低了日常能源消耗。这座住宅是否反映了您对于如何建造家庭空间的看法呢?

我认为建筑的大小与人们之间距离的概念密切相关。阿尔托自宅的尺寸是他对于个体间适当距离概念的一个很好的例子。此外,阿尔托不仅有设计建筑内部的能力,还能仔细考虑并创建居住者之间的适当距离,无论是在建筑内部还是周围社区。

例如,玛丽娅别墅是一座大型住宅;然而,在设计时,它的设计着眼于许多人聚集在一个地方时发生的社会动态,以及在该地区田园诗般的氛围中如何保持人与人之间的适当距离。

他并不仅仅考虑数值尺寸,例如平方米,而是将建筑概念化为衡量个体之间、人与自然之间、人造和自然世界之间距离的一种手段。我认为,在这方面阿尔托有着非常精致的平衡感。

合适尺寸的感觉是主观的还是客观的?

这方面的一个例子是京都的一个町屋,门楣非常低,身高约175厘米的人必须弯腰才能进入,这可能对所有体型的个体都不舒适。然而,身高超过180厘米的人也不一定会感到不舒服或不自在。这是因为该空间体现了创造者的真诚和诚实,以及他们的文化模式和尺寸系统。这种氛围在整个城市中都能感受到。我相信,人们可以立即感觉到建筑或其内部的大小适合特定城镇或地区的语境、传统和文化,同时感受到周围区域的规模、道路的宽度和相邻房屋之间的距离感。人类有一定的接受能力来理解陌生的规模或尺寸。

重要的不是180厘米的门高是否具有国际性或普遍性,而是一个具体建筑的氛围和尺度是否与地区、气候、历史和其他相关因素的尺度和氛围相符。如果我们去参观一位阿拉伯石油大亨的住宅,尽管尺寸和尺度不熟悉,但我们很可能会感觉到建造它的人是真诚的,并遵循了从该地区的文化和习俗中得出的尺度感。

与其强求一些东西,不如让自己被这些流动所引导,从超越自己创造的东西中学习。这种谦逊是很重要的。

从一个日本建筑师的角度来看,你对现代西方文化有什么印象和见解?

我认为,一神论和多神论国家的思维方式存在显著的差异。这不是哪种方式更好或更差;这些只是不同的思维方式,影响到人们如何看待自己,以及如何与周围环境建立关系。

我就不能用一神论的方式思考。它已经在我的身体里根深蒂固,在与自然、朋友或任何地方的互动中,有各种存在看护我或支持我。对我来说,几乎不可能摆脱这种思维方式。

我觉得芬兰是一个传统上与我们的东方意识相通的国家。有一种信仰认为自然界中有多种精灵,例如在布里格曼的复活教堂或西伦的奥塔尼米教堂中可以看到这种信仰。庆祝森林中也有神灵存在的感觉让我感到非常平静;当我在西方遇到这种事情时,我会感到欣喜。

这对我们如何思考时间有一定影响。我认为时间有两种主要的流动方式。第一种是线性的,科技不断发展,社会不断进步。第二种是循环的,类似于太阳的升起和落下,没有进步或演化。简而言之,从事科学工作的人倾向于认同历史性的进步轨迹,即技术和人类的智慧在不断提高。例如,十年前的苹果手机功能不如现在的型号。相反,从事人类研究的人不认为莫扎特创作的音乐或者两百多年前陀思妥耶夫斯基所写的文学作品不如当代创作。

我认为我们目前正处于一个西方个体开始质疑线性时间应用于生活各个方面的时代。我希望西方能开始接受时间的周期性概念,让这个世界成为一个人们可以相互连接和共鸣的地方,而不受其国籍或种族的影响。

我特意使用了 "东方 "和 "西方 "这两个词,但如果不使用这样的代名词,说 "线性 "或 "周期性 "会更准确。

虽然你表达了对多神论和芬兰建筑的共情,但你的作品似乎具有强烈的西方几何学严谨性。为什么会这样?

我在美国看到的最东方的建筑是金伯尔美术馆。我感到它比我参观过的任何其他建筑都更具有东方建筑的特点。金伯尔美术馆是一个组织和秩序的领域,但这种秩序或几何形式并不是进化的,而是旋转或循环的;去了某处又回来了。我感到它具有难以想象的深度。

曼陀罗代表循环,但它也使用非常严格的几何学。通过使用其独特的节奏、韵律和几何学中的重复,有一种循环的感觉。我对这种东西非常感兴趣。

我认为它并不简单;相反,它非常复杂,有各种矛盾的元素并存。曼陀罗和金伯尔美术馆以三维或四维的方式表现了这种复杂性,并证明了几何学的严谨性并不一定与周期性世界相冲突。虽然康的建筑有以圆锥线为基础构造的拱顶,曼陀罗是一个圆圈,但我想强调的是,这并不仅仅是在平面或截面中使用圆形。

好的建筑不仅仅是一个词可以描述的。用语言来表达四维循环世界非常困难。我认为只有亲身体验才能理解。设计师的思想也会来回反复,回归原点,并穿越许多不必要的东西。我认为深度就是这样建立起来的,它是复杂的非线性思维的结果。

关于它与环境的关系,玛丽娅别墅采用了L形的结构,围绕着一个庭院,类似于阿尔托的自宅。在您的书《感性思考建筑》中,你建议将庭院朝南打开会更合适,因为它顺着阳光的路径。但是,他没有将房子朝向太阳方向,而是在相反的方向上创造了一个庭院,以更受保护的方式与自然互动。是什么促使阿尔托优先考虑背弃周围的自然?

我认为,阿尔托的建筑之所以难以用简单的语言表达并解释,正是因为他的设计非常复杂而微妙。两种相互冲突的与自然互动的方式并存:一方面,人们意识到与自然的连续性,倾向于利用当地的自然特征;另一方面,人们需要创造一个避难所,让个人在面对自然的严酷时感到安全。最明显的例子是他的实验室住宅,它牢固地扎根于自然地面,但被高墙包围,以保护人们免受自然的侵害。我认为阿尔托在他的建筑中一直在深入思考这种复杂的自然与人类及其周围环境之间的关系。

无论如何,芬兰非常寒冷,不受欢迎的动物也在游荡,所以当然需要考虑阻隔自然的重要性。

站在阿尔托的住宅前,人们注意到面向街道的外墙上没有太多开口。从这个角度看,黑白色的外墙可能会给人一种不受欢迎和难以穿透的印象。

是的,但我们不要忽视周边没有墙,这与日本不同。道路两旁和邻近房产的边界都没有墙;只有像农场一样的原木栅栏,反映了芬兰土地的连续性。

如今尤其是在日本,人们似乎非常渴望拥有土地和住房。他们经常过度表达从这里到那里的区域是他们的所有物。我认为这是对土地和空间稀缺性的一种反应。

然而,无论我们相信或感觉如何,个人永远不可能拥有100%的土地。吹过那里的风属于所有人,照耀那里的阳光也属于所有人。那里的土壤也与邻近地块的所有边缘相连。划定界限并不容易。在地下或地上,当你超过一定距离时,它就不再被认为是任何人的所有物。阿尔托没有创造独占性的房屋或社区,他非常注重土地的连续性。我认为这在他的自宅中非常明显。

你告诉我,"只有那些感情指向未来、想象力丰富的人,才能看到光线照射在空白、抽象的墙壁上的美感。" 为什么阿尔托在他自己的房子里打破了现代主义的抽象美学规则呢?

我认为现代主义在很大程度上根植于建筑师设计为中心的理念,并坚持一种人类无懈可击的观念。人类有一种傲慢,认为如果设计出了一个理想的城市或社会的理想蓝图,它将完全按照其意图实现。这种傲慢,在现在被认为是自负的,他们认为设计者可以从神的角度控制一切,并且有可能在世界任何地方建造类似风格的房屋和建筑。

我认为他们对人类的力量拥有极大的信心。然而,即使建筑和当时的背景基于这种人类力量的构建,人们也会衰老,某一时刻失去健康、力量和财富。人总会有失去一切的时候。

从这个角度来看,我觉得芬兰的气候让人不得不面对人类的脆弱性。那里非常寒冷,阳光很少。在这样一个严酷的环境中,我们被迫面对自己身体和精神上的脆弱性,往往仅仅因为身处其中而变得沮丧。这种挣扎在某种程度上是内在的。我感觉芬兰的建筑和文化源于这种情况,我对此深受共鸣。这可能是芬兰建筑高质量的原因,它在顺境和逆境中都能拥抱身体和灵魂。

一个国家有时是有活力的,有时是没有活力的。当一个社会失去活力时,那些在信仰和希望时期创造的东西会显得疯狂甚至可怕。

在你过去的一篇文章中,我记得你感叹现代运动对黑暗的根除,造成了平坦和平庸的空间。阿尔托的住宅是现代主义运动中迷恋整洁、卫生和健康的一部分。你能告诉我这个住宅里还有多少阴影或模糊性吗?在建筑内部它们还可以在哪里被发现?

我刚才提到了现代主义的问题;但是,我也相信现代主义开辟了很多可能性,可以用非常积极的方式来使用。在阿尔托的作品中,它们得到了研究并带来了很多益处。举个例子,大玻璃板是现代主义的产物——在芬兰,由于它们能使大量的阳光和热量进入建筑物,具体来说,在冬季证明是有益的。我觉得有趣的是,在细节中,现代主义的发明很好地融合了手工制作的温暖、天然材料的应用和功能的高性能。

我认为,在阿尔托的作品中,黑暗或神秘的存在体现在桑拿房中。阿尔托的许多住宅都有桑拿房,它们的形式非常传统。这些都是本土的、黑暗的、神秘的地方,脱离了现代主义的精神。

阿尔托的自宅有一个独特的特点,使其有别于其他住宅,它既是一个生活空间,又是一个办公室。位于房子一楼的起居室,经常被用来进行办公会议。你是如何设想住宅空间与工作区域的互动的?

我选择阿尔托的自宅,是因为我被他的公平感所吸引。阿尔托的设计理念是一致的,不管是他自己的住宅还是别人的。许多建筑师在为别人设计高度实验性的住宅的同时,却保持自己的住宅较为保守,但阿尔托没有这样做。我觉得,他一定有一种自由主义和公平的意识。这种态度可能出现在家庭和工作空间的融合上。

我认为阿尔瓦-阿尔托相信以住房原则设计所有类型的建筑物;即工作场所也应该是一个家,一个人类居住的巢穴,是人们归属的地方。无论是教堂、音乐厅、大学还是村委会,所有这些建筑的起点都是一个温暖地欢迎人的身心的家。我相信,阿尔托一定明白,在恶劣的环境中,人的存在、温暖和工艺等方面的意义和价值。在现代主义中,人们常常强调工业化或大规模生产的功效;然而,我相信,在理解这些发明的重要性的同时,阿尔托也开发了细节、施工方法和规划,以唤起人类的温暖感。

至于家庭和工作空间的融合,我认为这与人们不能孤单生活的事实有关。人是一种群居动物,当他们聚集在一起时,会变得更加温暖。在人口密度较低的芬兰,无法感受到他人的存在可能是相当可怕的。

在他家的一个屋檐下,每个人都有一个地方可以做一些事情:包饺子、读书、画建筑图,感受他人的存在。我认为,当时的芬兰社会比我们今天更宽容,更愿意分享空间。

住宅的氛围和使用与办公室的结合,并不完全是阿尔托的个性使然。我相信,他的妻子艾诺的存在在当时也是非常重要的。阿尔托似乎有性别平等的意识,他相信女性可以像男性一样在社会和建筑业中取得进展。这是阿尔托的另一个特点。当你参观那座住宅时,你可以看到他社会进步的观点。它真正告诉我们阿尔托的人道主义公平。

2022年12月29日

堀部安嗣: 私の師匠である益子義弘先生が、アアルトのことが好きで、君もぜひフィンランドに行って、アアルトの作品を見るといいよ、と言ってくださったのがきっかけです。実は、当時はアアルト自邸を見ても今ほどピンときませんでした。なんだ普通の家じゃないか、という感じで、そこまで刺激がなかったことを覚えています。ただ、フィンランドの風土や、日本人に近くシャイで温厚な性格のフィンランド人との触れ合いを通じて、フィンランドに対してのシンパシーみたいなものを、非常に強く感じ、また行きたいという風に思いました。その後、フィンランドには都合4、5回は行っていると思います。最近は、アアルトの作品、特に自邸に対しての素晴らしさを強く感じるようになってきました。これは自分の経験や年齢、あるいは、建築に対する理解みたいなものが深まってきたからなのではないかと思います。

あるテキストの中で、興味深い説話を引用されていたと思います(「建築への憧れと絶望」『JA 90』2013) 皇帝が宮廷画家に「描くのが難しいものは何か」と尋ねると、宮廷画家は「鬼を描くのは簡単だが、犬は難しい」と答えた。見慣れたものに対して私たちは、すぐに間違いに気づいてしまうからだ、と。それは、建築に対しても同じことだとおっしゃっていますが、アアルト自邸は、犬的なものなのでしょうか?それとも鬼的なものなのでしょうか?

時間の経過によっても変わるものだと思いますが、おそらく建った当初は、かなり鬼的な要素があったと思います。けれども、時代や社会の変化、それに建築の技術や文化の変化を経て、年々、犬的な側面が強くなってきたのではないかと思います。

いい建築には、そういう変化があるように思います。当時は、非常にラディカルで過激だったものが、今となってみれば、とても穏やかで、表現が丸くなっているということがよくあります。アアルト自邸が犬的な側面を持ち始めたのも、等身大の人間の心身のことを、アアルトが理解していたからだと思います。

人間の心身への正直さみたいなものを外した鬼的な表現というのは、やはり長く保たないもので、人から飽きられてしまう性格のものになるのではないかと思います。

建築には大きく分けると、二つの役割があると思います。一つは花火のような役割で、花火を打ち上げて人々を鼓舞したり、奮い立たせたりして、元気を煽っていくような、お祭り的な役割というのも当然あると思います。一方で、漢方薬のような時間と共に効能が現れてくるような、地味だとしてもどんな心身の状態にも無理や負担のない、そういった建築の役割も必要だと思います。最も美しいものだと私は思っていますから。

アアルト自邸は、サイズが控えめで日々のエネルギー消費も少なく、サスティナビリティという点において非常に良いモデルになるのではないかと思います。こういった住宅がやはり、生活空間としては適切であるとお考えでしょうか?

建築のサイズ感というのは、人と人との距離感のことだと思います。そして、アアルト自邸のサイズというのは、彼の考える人と人との距離感の適切な解であったのだと思います。また、彼は建物内部のことだけではなく、隣人や地域の中での距離感といった複合的な内外の人との距離の調整やデザインが、非常に達者だったのではないかと思います。

例えば、マイレア邸は非常に大きな住宅ですが、そこに大勢の人が集まった時のことも考えていたのだと思いますし、あの地域の牧歌的な風土や雰囲気の中での、人と人との適切な距離感を考え、あのサイズ感になっているのだと思います。

つまり、何平米だとか数値的な広さというよりも、人と人との距離感、自然との距離感、そして、人工と自然との距離感を測る役割として、建築を考えていたのだと思います。アアルトは、その辺のバランス感覚が非常に長けているのだと思います。

適切なサイズ感というものは、主観的なものなのでしょうか?それとも客観的なものなのでしょうか?

例えば、京都の町家は、鴨居も非常に低くて、身長が175センチぐらいある人は、必ず頭をかがめないといけなかったりしますし、必ずしもどんな体型の人にも快適かと言えば、そうではないと思います。けれども、おそらく身長が180センチ以上の人がそこに行っても、意地悪を感じたり、居心地の悪さを感じるかというと、そんな事もないと思います。それは、その文化や寸法体系を作った人々の、誠実さや正直さが、空間に表れているからだと思います。そういったものは、街全体から感じられるものです。周囲のスケール感であったり、道路の広さであったり、隣の家との間隔みたいなものを相対的に体の中で感じとって、この街、あるいは、ここでの伝統や文化の中では、このスケールがちょうどいいことなんだということを、瞬時に感じ取れる力が人間にはあるのではないかと思います。それが、馴染みのないスケール感やサイズ感であったとしても理解できるような、ある種の感受性があるのでしょう。

大事なことは、ドアの高さが180センチしかないことが国際的ではないとか、ユニバーサルではないとかそういうことではなく、地域であったり、風土であったり、歴史であったり、そういったもののもつスケール感や雰囲気と、具体的な一つの建物の内部の雰囲気やスケール感がフィットしているということなのではないでしょうか。例えば、逆に私たち日本人が、アラブの石油王の家に行ったとします。それが体験したことのない寸法や、スケール感であったとしても、ここを作った人たちは誠実に、ここでの文化や慣習の中から、このスケール感を導き出していることを、私たちは感じることができるのだと思います。

ですから、そこに何かを無理やりクリエーションするよりも、それらの流れに身を任せ、一個人のクリエーションを超えた何かに教わっていく。そういった謙虚さが大事じゃないかなと思います。

日本の建築家として、現代の西洋の文化に対する印象や、お考えを教えていただけますでしょうか?

一神教の国と多神教の国、その考え方の違いというのは、非常に大きいなと思います。どっちが良い悪いということではなく、単に自分自身や周囲との関わり方への違いがあるのだと思います。

私は一つの神を信じている人間ではなく、どんなところにも何か自分を見守ってくれる存在がいたりだとか、自分を支えてくれるものが自然界の中にあったり、友人の中にあったり、さまざまなところに存在しているという、そういう考え方からどうしても抜け出せないところがあります。それはもう身体にもすり込まれてる、という感じでしょうか。

一方で、フィンランドというのは、我々とその辺の感覚が似ていて、自然の中にも、いくつも精霊が宿っているという考えがあると思います。典型的なのが、ブリュックマンの教会や、オタニエミのシレンの教会でしょうか。ああいう森の中に神様がいる、というような感覚に出会うと、非常に心が穏やかになるというか。西洋の中にある、ああいうものに触れると喜びを感じますね。

時間に関しての考え方の違いもあるのだと思います。私は、大きく分けると二つの時間の流れ方があると思っています。一つは、一直線に進んでいく時間の流れ方。どんどん技術は進化して、良くなっていくという時間の流れ方です。もう一つは、ぐるぐると循環した流れ方。太陽が昇って、また沈んでいくような、進化もしていなければ、進歩もしていないという循環的な流れ方です。大きく言うと、理系の人は、技術はどんどん進化して、人間はどんどん賢くなるといった進歩史観を持っているのだと思います。例えば、10年前のiPhoneは今と比べると使いものにならないですよね。一方、文系の人は、200年以上前のモーツァルトの曲や、ドストエフスキーの書いたものが今よりも劣っているとは考えません。

今は、西洋の方々も、そういった一直線に流れる時間に対して、大きな疑問を感じてきている時代なのではないかと思います。人間は、別に進歩も進化もしていないというような循環した時間の流れ方に、西洋の方々も気づき、国籍や人種を超えて共鳴し合う世界へとなっていくといいなという風に思っています。

あえて、東洋とか西洋という代名詞を使って説明していますが、そういった代名詞を使わずに、直線型なのか、循環型なのかという言い方をした方が的確ですね。

多神教やフィンランドの建築に共感を示されている一方で、あなたの作品には、西洋的な強い幾何学の厳密性を感じます。それはなぜでしょうか?

実は、アメリカに行って一番東洋的だなと思ったのは、キンベル美術館でした。他のどんな建築よりも、遥かに東洋的な建築だという風に感じました。キンベル美術館は、まさに整理整頓、秩序の世界ではあるのですが、その秩序というか幾何学というものが、先ほど述べたように、進化的なものではなく、回転していくというか、循環していくというか、またどこかに行ってまた戻ってくるというか、そういった奥行きと深さを持っているように思いました。

例えば、循環を表している絵には曼荼羅がありますが、曼荼羅にも非常に厳格な幾何学が用いられていて、テンポやリズムの中に円を意識していくというか、幾何学の中に丸を意識していくというような感じがあります。そういうところに、私は非常に興味があります。

複雑なのだと思います。シンプルではない。非常に複雑でいろいろな複合的なものが絡み合って、さまざまなアンビバレンツなものが同居しているというか。それを三次元的、あるいは四次元的に表しているのが曼荼羅であり、キンベル美術館ではないかなと思います。厳密な幾何学が循環的な世界と相反するものであるかというと、必ずしもそうではないと思います。つまり、キンベル美術館には、サイクロイド曲線がありますし、曼荼羅にも円の形がありますが、平面や断面でそういった形を使うことが重要なのではないと思います。

本当に一言では言えないですよね。良い建築って。四次元的に循環している、あの世界を言葉で表すというのは難しく、体感する以外ないのだと思います。設計者の考えも本当に行ったり来たりしながら、元に戻ったり、無駄がいっぱいあったりするのですが、そういった複雑な思考を続けたからこそ、あの奥深さがあるのではないかなと思います。直線型の思考からは出てこない複雑さだと思います。

自然との関係に関して言えば、マイレア邸もアアルト自邸と同じように、L字型のボリュームが中庭を囲んでいます。あなたは著書『建築を気持ちで考える』の中で、マイレア邸の中庭は、方角に従って素直に南側に向けて配置した方が良かったのではないか、とおっしゃっていますが、実際は、太陽の方角に反して、アプローチのある南側と逆方向に中庭を開き、自然との関係を作ろうとしています。アアルトが太陽の方角よりも、周囲の自然から背を向けることを優先した理由は何なのでしょうか?

アアルトの建築がなかなか言葉にしづらく、そして単純な言葉では語れない理由は、まさにその複雑さと繊細さにあるのだと思います。自然に対しての連続性を意識したり、風土を生かそうという気持ちがある一方で、自然の厳しさに対して、人の安心できる居場所を作らなければいけない、という相反する自然への向き合い方みたいなものが共存しているからだと思います。一番わかりやすいのは、ユヴァスキュラの夏の家ですね。自然の大地にしっかりと根を下ろしながらも、高い壁を建てて自然をフレーミングしたりして、自然から身を守るような設えをしています。そういった複雑な自然への向き合い方や、人間と自然との微妙な関係性を、アアルトは深く考え続けていたのではないかと思います。

フィンランドは、とにかく寒いですし、歓迎されない動物も入ってきたりしますから、自然を遮断することの重要性というのは、あの風土においては当然考えなければいけないことなのだろうと思います。

アアルト自邸の前に立つと、道路側のファサードには開口部が少ないことに気づきます。黒と白の外観は、無表情で自閉的なものにも見えますが、その点についてはどうお考えでしょうか?

とはいえ、道路沿いや隣地境界には、日本のような塀がないことがわかると思います。隣地境界には、塀の代わりに、牧場の丸太の柵のようなものがあるだけなのですが、何かフィンランドの大地の連続性みたいなものが意識されているのではないでしょうか。

今日の、特に日本では、土地や住まいに対する所有への欲望というものが、とても強いように思います。ここからここは自分の持ち物だ、というようなことが過激に表現されているのですが、それは逆に、それだけ土地に余裕がないことの表れなのだと感じます。

ところが、その土地をその人が100%所有しているのかというと、もちろんそうではなく、そこに入ってくる風はみんなのものですし、そこに降り注ぐ太陽もみんなのものです。そこの土も、隣の家からずっと繋がってきているものですので、そこに線を引くということはなかなかできないわけです。地下や上空も、ある距離を超えると、もはや所有物ではなくなりますよね。アアルトは自分だけが独占するような、町や家を作るのではなく、やはり大地の連続性というものをとても意識していたのではないかと思います。それは、あの自邸にもすごく表れているように思います。

「真っ白い抽象的な壁に当たる光を見て美しいと思えるのは、気持ちが未来に向いている人や想像力が豊かな人だけなのです。」(『建築を気持ちで考える』TOTO出版 2017年)とおっしゃっていましたが、アアルトはなぜそうしたモダニズムの抽象的な美学を自邸において表現しなかったのでしょうか?

モダニズムというのは人間、あるいは建築家の設計主義的な理想像を強く掲げることで、人間の無謬性みたいなものを信じていたのだと思います。例えば、理想の設計図を描いて、理想の都市像や社会みたいなものを描けば、その通りに実現していくというような、どこか人間の驕りのようなものがあったように思います。設計者が神の視点に立って全てをコントロールすることができ、世界中どこにでも同じスタイルで住宅や建築が可能であるという、今となってみれば驕りとしか思えないようなことが繰り広げられていたのだと思います。

つまり、人間の強さみたいなものを非常に信じていたんだと思います。ところが、その人間の強さみたいなものを基準として、建築やその時代の背景を作ったとしても、人間というのは老いていくもので、元気なときばかりではなく、権力を失うときもあれば、お金がなくなるときもある。そういうときが必ず来ますよね。いいときばかりではない。

フィンランドは、そういった観点から見ると、人間は弱いものであるということを自覚できる風土なのではないかと思います。つまり、非常に寒い。それから晴れる日が少ない。そんな過酷な環境の中では、ただそこにいるだけで憂鬱になっていくような人間の弱さに対して、肉体的にも精神的にも向き合わざるを得ないわけです。そういう環境への葛藤が本質的にあるのだと思います。フィンランドの建築や文化は、そういった状況から出てきているものだと思いますし、私はそういうところに非常に共感します。そのことが、元気な時も病めるときも、心身を包み込んでくれるようなフィンランドの建築の質の高さにつながっていったのではないかなと思います。

やはり国も元気なときもあれば、そうでないときもあります。社会に元気がなくなってきたときに、自信や希望に満ち溢れていた時代に作られたものというのは、どこか狂気に感じられたり、怖いものになっていくのだと思います。

あるテキストの中で「街や建築が闇を嫌い、異常なまでにフラットで清潔になってしまった」ということを書かれていたと思います (「人に寄り添うかたち」『JA 90』2013) アアルト自邸はまさに、清潔さや衛生面、それに健康といったことに取り憑かれていたモダンムーブメントの渦中にあった住宅ですが、そこに陰りや曖昧さのようなものは、感じられるのでしょうか? また、どの部分にそういった性質が残っているとお考えでしょうか?

モダニズムの問題みたいなことに触れましたが、モダニズムが切り開いたポジティブな側面もたくさんあると思います。それは、アアルトの仕事の中にも非常に良い形で表れていると思います。例えば、大きなガラスは、モダニズムの産物ですが、フィンランドでは特に、冬に太陽の日差しや熱をたっぷりと取り入れるために非常に有効なものだと思います。そういったモダニズムの性能の高さと、ディテールにおける手仕事のあたたかさや、自然素材の使い方とが良い形で融合しているというところには魅力を感じますね。

そして、アアルトにおける暗がり、あるいは神秘性というものは、サウナに表れているのではないかと思います。多くのアアルトの住宅にはサウナがあり、それらは非常にトラディショナルな形をしています。そこはモダニズムの精神から切り離された、土着的で暗がりをもった神秘性のある場所になっていると思います。

アアルト自邸は、家でもあり仕事場でもあるという、他の住宅とは決定的に異なる特徴があります。一階のリビングは、仕事のミーティングでも頻繁に使われていたようですが、こういった仕事場と生活空間の関係性については、どうお考えでしょうか?

この自邸を選んだ理由は、アアルトのフェアさみたいなものに惹かれたからです。アアルトの態度には、それが自邸であるとか、他人の家であるとかといった違いを感じません。他人には非常に実験的な家を作る一方で、自分の家は保守的であるという建築家も数多くいますが、アアルトはそうではない。そのリベラルさというか、人間的なフェアさみたいなものを非常に強く感じます。そのことは、職住が一体になっているということにも繋がるのだと思います。

アアルトは住宅を基本に考えていて、仕事場も住宅であり、そこが人間の巣であり、人間の居場所であると考えていたのではないかなと思います。それが教会であっても、ホールであっても、大学であっても、それに村役場であっても、多くの人の心身を温かく受け入れてくれる住宅というものが、考えの起点になっているのだと思います。人の気配や、ぬくもり、あるいは手仕事みたいなものが、ああいう厳しい風土の中では、どれだけ貴重なものなのかを、アアルト自身よくわかっていたのだと思います。モダニズムは工業化や、量産化の有用性から語られることが多いですが、アアルトは、そういったものを大事にしながらも、人のぬくもりを感じさせるディテールや構法、それからプランニングをしていったのではないかと思います。

人は、一人では生きていけないということとも関係しているのだと思います。人も群れをなす動物の一種ですので、みんなで集まれば、それだけ温かくもなります。それに、人の気配が感じられないということは、人口密度の低いフィンランドにおいては、非常に怖いことなのではないかなと思います。

建物の一つ屋根の下では、人の気配を感じながら、みんなで本を読んだり、図面を引いたり、何か押しくら饅頭をしているような状態でいる。当時のフィンランドは、そういったことに関して、いまの我々以上に許容できた社会であったのかなと思います。

あの住宅の雰囲気、そして事務所を併用しているということに関しては、アアルトだけの性格からくるものではなく、当時の奥さんであるアイノの存在というものも非常に大きいと思います。当時からアアルトは男女の平等、つまり女性も社会に進出して、男性と何ら変わらなく建築の仕事ができるという、そういうことへの理解があったんだと思います。そこにも、アアルトの特徴がみてとれます。アアルトが社会的にも先進的な眼差しを持っていたということが、あの自邸に行くとよく伝わってきます。人間的なフェアさに対する眼差しですね。

2022年12月29日

Yasushi Horibe: My teacher, Yoshihiro Masuko, held a great admiration for Aalto and told me to travel to Finland to see his works. To be honest, upon my initial visit, I was not particularly impressed with Aalto’s own house; I remember thinking, “It’s just an average house.” However, the natural features of Finland and the interaction with the reserved and gentle Finnish people – akin to the Japanese – evoked a deep sense of personal empathy towards Finland. Since then, I have returned to the country on four or five occasions and recently, come to appreciate Aalto’s work, particularly his own house. I attribute this to my experiences, my age, and my growing understanding of architecture.

IN YOUR TEXT (“MY ADMIRATION AND DESPAIR FOR ARCHITECTURE IN JA 90/2013”), YOU NOTED AN INTERESTING ANECDOTE: A KING ASKING A PAINTER WHAT WAS THE MOST DIFFICULT THING TO PAINT. THE PAINTER REPLIED THAT IT WAS EASY TO PAINT A DEMON BUT NOT A DOG—WE WOULD IMMEDIATELY RECOGNISE MISTAKES IN THE REPRESENTATIONS OF WHAT WE KNOW VERY WELL. YOU ALLUDE TO ARCHITECTURE, SAYING THAT DESIGNING A CALM-LOOKING BUILDING IS LIKE PAINTING A DOG. IS ALVAR AALTO’S HOUSE MORE LIKE A DOG OR RATHER LIKE A DEMON?

I think it has changed over time. Probably, when it was initially constructed, there was a very demon-like appearance to it. However, due to changes in both social and architectural techniques and culture, I think the dog-like aspect became more prominent.

In many cases of good architecture, this process usually happens; what once was very radical and avant-garde soon becomes soft and more relaxed in expression. An important factor in Aalto’s house becoming dog-like with time is that Aalto understood a life-size person’s body and mind.

If the expression is demon-like and insincere to the human body and mind, it will not last long, and people will become fatigued with it.

Generally speaking, I think architecture has two primary roles. One is like launching fireworks, which raises people’s spirits; a celebratory role of architecture that encourages and inspires. On the other hand, there must also be architecture like Chinese herbal medicine, which shows its effects over time and which is not overpowering or burdensome to any physical or mental condition; it is quiet.

AALTO’S RESIDENCE IS MODEST IN ITS SIZE, EMBODYING A MODEL OF HIGHLY EFFICIENT SUSTAINABILITY, AND CONSEQUENTLY LOWER DAILY ENERGY EXPENDITURE. DOES THIS HOUSE REFLECT YOUR VIEWS ON HOW DOMESTIC SPACES SHOULD BE BUILT?

I think that the size of architecture is intimately tied to the concept of distance from others. The dimensions of Aalto’s own house are a fitting example of his ideas about the appropriate distance between individuals. Furthermore, Aalto had a keen ability to not only design the interiors of buildings but also carefully consider and create appropriate distances between the inhabitants, whether they be within the building or in the surrounding community.

For example, the Villa Mairea is a large house; however, it was designed with an eye to the social dynamics that occur when many people congregate in one place, and how the distance between people should be maintained in the idyllic atmosphere of the area.

Rather than considering only numerical measurements, such as square meters, he conceptualized architecture as a means of measuring the distance between individuals, between people and nature, and between the man-made and natural world. I think Aalto had a very refined sense of balance in that regard.

IS THE FEELING OF A SUITABLE SIZE SUBJECTIVE OR OBJECTIVE?

An example of this is a machiya townhouse in Kyoto, where the lintel is so low that a person of about 175 cm in height must bend to enter, which may not be comfortable for individuals of all body types. However, it is not necessarily true that those taller than 180 cm would feel uncomfortable or ill-at-ease. This is because the space embodies the sincerity and honesty of those who created it, along with their cultural patterns and systems of sizes. This atmosphere can be sensed throughout the entire city. I believe that humans can instantly sense that the size of the building or its interior is appropriate for the context, tradition, and culture of that particular town or area, while feeling the scale of surrounding area, the width of roads, and the sense of distance between neighbouring houses. Humans have a certain receptivity to understand unfamiliar scale or size.

What is important is not whether the door height of 180 cm is international or universal, but rather, whether the atmosphere and scale of a specific building align with the scale and atmosphere of the region, climate, history, and other relevant factors. If we were to visit the house of an Arab oil tycoon, despite the unfamiliar dimensions and scale, we would likely sense that the people who built it were sincere and followed the sense of scale derived from the culture and customs of the region.

Instead of forcing something, it is better to let oneself be guided by those flows and learn from something beyond one’s creation. This kind of humility is important.

FROM THE VIEWPOINT OF A JAPANESE ARCHITECT, WHAT ARE YOUR IMPRESSIONS AND INSIGHTS ON MODERN WESTERN CULTURE?

I believe that there is a significant difference between the ways of thinking prevalent in monotheistic and polytheistic countries. It is not about which one is better or worse; these are simply different ways of thinking that affect how people view themselves and how they build relationships with their surroundings.

I just can’t think in a monotheistic way. It has already been ingrained in my body that there are various existences that watch over me or support me in the interaction with nature, friends, or in any place. For me, it is almost impossible to get over this way of thinking.

I feel that Finland is a country that traditionally shares our Eastern sense. There is a belief that there are multiple spirits in nature, and examples of this can be seen in Bryggman’s Resurrection Chapel or Siren’s Otaniemi Chapel. Celebrating the feeling that there is also a god in the forest makes me feel very calm; I find joy when I come across such things in the West.

It has a certain impact on how we think of time. I believe there are two primary ways in which time flows. The first is linear, with technology continually advancing and society progressing. The second is cyclical, akin to the rising and setting of the sun, with no progression or evolution. To simplify, people working in sciences tend to subscribe to the idea of a historical trajectory of progress, wherein technology and human intelligence are constantly improving. For instance, an iPhone from 10 years ago is not as functional as the present-day models. Conversely, people in human studies do not believe that a piece of music composed by Mozart or a literary work written by Dostoevsky over 200 years ago is inferior to contemporary creations.

I believe that we are currently in an era where individuals in the West are beginning to question this linear manner of time applied to all aspects of life. I hope that the West will begin to embrace the cyclical idea of time and that the world will become a place where individuals can connect and resonate with one another regardless of their nationalities or races.

I am using the terms “East” and “West” deliberately, but it would be more accurate to say “linear” or “cyclical” without using such pronouns.

WHILE EXPRESSING SYMPATHY FOR POLYTHEISM AND FINNISH ARCHITECTURE, YOUR WORKS SEEM TO HAVE STRONG WESTERN RIGOUR OF GEOMETRY. WHY IS THAT?