ベアテ・ホルムバック:パラグアイの人は、自国のことを「陸に囲まれた島」だと表現するそうですね。荒れ狂う海のように簡単にはたどり着けないのだと。

アブ&フォント邸を初めて目にしたのは、バーバラ・ホイドンが編集を手がけた、テキサス大学オースティン校出版の『O’Neil Ford Duograph 5』という本でした。その家は、ソラーノ・ベニテスが彼の母親のために建てた家です。とても興味を惹かれたので、彼に直接連絡を取ってみたのです。そして2016年の春、学生たちを連れてパラグアイへ向かい、その家を訪問したのです。ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラやハビエル・コルヴァランの手がけたプロジェクトも見学しました。私たちが訪ねてきたことに彼は驚いていたようですが、時間を割いて快く歓迎してくれました。同じ年の暮れのこと、今度は彼をオスロへ招待して、私たちの大学内で作品のレクチャーをお願いしました。

この家には、さまざまな空間がありますが、それぞれの空間へのアプローチが一つではなく複数用意されている点が特徴ですよね。このように建物内を移動できることの面白さは、どういったところにあるのでしょうか?

そうですね。家というものはそのように開放的で、人々の生活を制限しないことが必要だと思います。この家に設けられたスロープの場合、人は階段よりもゆっくりと進みますね。ですが、人の動きはスロープの手前に設けられたスクリーンで隠されています。部屋同士は、つながりつつも全てが同時に見渡せるわけではありません。それぞれに流れている時間のスピードが異なっているのです。家が呼吸している、と言えますか。自由に移動できるということは、空間を考える上でも非常に触覚的で具体的な性質の一つだと思います。

一方で、行き止まりの空間が持つ確固たる魅力も否定できません。門によって閉ざされているという意味で、このアブ&フォント邸も行き止まりの建築なのです。通りからこの家へと向かっていくと、背の高い中庭の壁、そしてエントランスの門が見えてきます。そこには明確な境界線が作られています。そして、中へ入るとそこがまるで別空間のように感じます。敷地全体が家となっているのです。つまりは、今まさに始まったはずの建物へのアプローチもそこで終わってしまうのです。

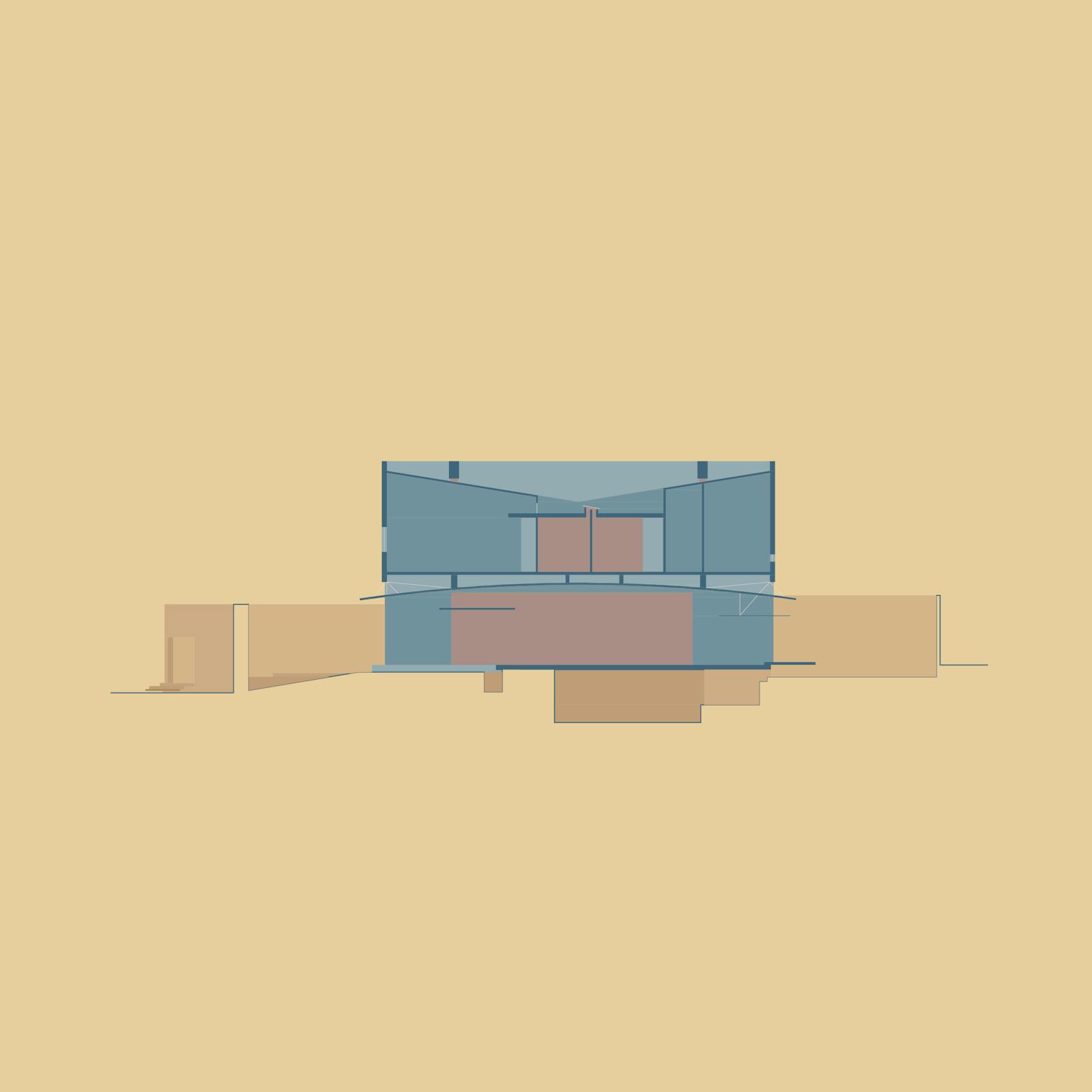

歩みを止め、その囲われた空間を見渡してみます。メインスペースとなる空間の床は、地面から持ち上げられていて、強い存在感が感じられます。フィーレンディールトラスから吊り上げられたセラミックのスラブ天井は素晴らしいものですよね。その緩くカーブした天井と、持ち上げられた床との間の空間には、上下からの圧縮力が働いているように感じられます。まさに、ここで生活が展開されるのです。

使用されている素材に関しては、レンガが多いですよね。ガレージのドアのような可動式の木の素材も気になりますが、素材に関してはどうお考えですか。

木のパネルと重いチェーンによって、空気の流れを変えたり、日差しを遮ることもできるわけですが、中世的なギミックと表現ですよね。

実用性によるものですが、魔術的な空間の魅力を感じます。私には、その木のパネルに取り付けられたチェーンが、まるで鳩時計のように正確に動き出し、内部の空間を閉じたり、開いたりして、クライマックスを演出する建物の姿が想像できるのです。鉱物のように動かないはずの建築とは対照的なこのフィクショナルなリズムは、石の中の時計、のイメージとでも例えられるでしょうか。

パラグアイは、ヨーロッパの気候条件とは大きく異なりますよね。そうした南方のエキゾチズムは、北方の建築家にとってどのように受け止められるのでしょうか?

内部と外部の関係に関しては得るものが多いですね。ですが、北欧のような気候の中で建築を作る難しさにも感謝しているのです。寒冷地であるという外的な制約がありますから、建築家として探求したいことの全てを実現することは難しくなります。ですが、だからこそ作品が個性的なものになるのだと思います。アブ&フォント邸のメインスペースには確かに壁が存在していません。内部空間そのものがそこにはあるのでしょう。スロープのスクリーンや回遊導線、そして舞台のように高く上げられた床。演劇的なシチュエーション。そう、これこそが私たち北方の人間が学び、考えるべきことなのでしょう。建築を通して実現されたパフォーマンス性の高い生活の姿です。

この家では、その構造的な発明が家族の集まるリビング空間に現れています。主構造と空間との関係についてはどうお考えですか?

アブ&フォント邸においては、構造体の存在自体もそうですが、構造が空間を形づくるその方法自体が美しいですね。強烈で独創的なレンガの構造体が、実は家族の集う空間のために選ばれたものであると気づくでしょう。家は誰かと集まるための空間であり、何かを共有する場所であるべきだという意識が感じられます。

私がこの家に興味を持っているのはおそらく、そこにエートスを感じるからでしょう。それは、家族が集まり幸福を感じることによって作られるものです。もちろん家の構造的なアイデアは魅力的ですし、素材の使い方も斬新なものだと思います。ですが、私の感動はそうした大胆な試みが、押しつけがましく主張していないことにあるのだと思います。ただ必要だから、そこにあるといったように。結果的に、ソラーノさんの母親が安心して過ごし、家族が集る安心した世界をつくりだそうとする意思が感じられます。

私たちマンタイ・クラは、これまでに実現したプロジェクトは多くありません。ですが、私たちにとって構造というものは常に建物のアイデアと深く結びついているものです。ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラはレンガ使いの名人ですよね。それに比べて私たちはもっとシンプルな方法ではありますが、どちらの事務所にとっても、構造の存在は空間を考える上で極めて重要だと思います。そうでなければ面白くありません。

私たちの場合、構造の存在は不可欠です。構造は、物事の相互関係を理解させてくれるものです。世界のより大きな次元との関係を構築する存在、例えば、重力、空間、時間、あるいは、近づきたくても近づけない、見たくても見ることのできない、そうした無形の現象と関係を結ぶきっかけとなる存在なのです。

空間体験と構造的なアイデアとが結びついた建物には、実存的な感覚が宿るのだと思います。世界の他の地域と同じように、ノルウェーのほとんどの建築物は面白くありません。たいていの人は、写真映えする商品としての建築に興味を持ったとしても、それが環境に対していかに有意義な相互作用をもたらすかといったことには興味がないのです。

大昔の話になりますが、私が学生だったころは違いました。オスロの建築大学の教授の一人にスヴェレ・フェーンという人がいました。彼は、コンストラクションという概念に取り憑かれていました。そこで私たちは空間と素材を関係づけるには構造的なロジックが必要であることを教えられました。構造は建築の主人公として、空間の質と生活の質、その両方に必要とされるものなのです。

私はこのロジックにこそ、建築における永遠の可能性を信じていますし、実務的な側面からそう学生に伝えています。あらゆることが可能になり、あらゆる形が物理的に作り得る今日です。私たちは一体何を見て、何に囲まれているのか、そうしたことを考え理解していなければ、世界から阻害されていくように感じます。自身の感覚を通じて、空間や場所とつながることは、人間の根源的な欲求なのでしょう。

アブ&フォント邸では、構造は装飾的なものではなく、構造としての本来の目的を果たしています。母親の寝室の写真をご覧になりましたか?梁と外壁との間に鉄の補強が見えるでしょう。こうした仲間外れの要素も、空間に心地よさを作り出す要因なのかもしれませんよね。

ノルウェーのアカデミックな建築の世界においても、こうしたテクトニクスを重視した建築は減ってきているようですが、その原因はどこにあるのでしょうか?

BH: 例外もありますが、大量生産される建築に関しては、全くその通りだと思います。莫大な資金が流入したからでしょう。ノルウェーは石油を発掘したのですが、石油は富をもたらしますよね。それで不動産も発展したのでしょう。クライアントは自分自身のために建築を考えなくなり、むしろその出口戦略を考え始めます。要は、クライアントと建築家との対話が、永続的なものから短期的に回収できるものへと変化したのです。建物は市場の需要を満たす必要がありますから、建築は商品となり下がってしまい、その質について深く議論されることがなくなりました。リスク回避の考え方も、建設に大きな影響を与える要因です。過去数十年の間に、建築家の仕事を管理するシステムや役割は劇的に増加しましたし、プロジェクトやそのプロセスは、リスクを回避するために標準的であることを強いられるのです。

高い質を担保しながら、テクトニクス的にも面白い建築を作ろうとするならば、頑なに信念を貫き通す必要があります。いや、安全でかつ簡単な解決策もありますが。標準的な仕様に従いながら、うまくそれらを隠蔽し、表面がまだ綺麗なうちに腕の良いカメラマンに撮影してもらえば良いのです。

やや哲学的な問いになってしまいますが、建物の構造自体に自律性や可塑性が担保されていさえすれば、実はそれだけで十分なのではないでしょうか。つまり、そうした構造を持つ建物は、特定のプログラムに縛られることなく、将来的に別の用途の建物に変更することができるのではないでしょうか。どうでしょうか。そうした問いかけをクライアントにもされたりしますか?こうした建築家の野心は理解され得るものでしょうか?

ほとんどの建築は本当にそうですよね!アブ&フォント邸の地下には、屋根を支える奇妙な、しかし美しいレンガのトラスがありますよね。いくぶん曖昧な空間なのですが、そのトラスのおかげで空間が引き締まっているように感じます。その地下空間は、家族の誰かが使う予定で作られたものなのですが、私たちが訪れた時には、すでに竣工から10年が経っていて、ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラの事務所として使われていました。

建築家として、あるいはビルダーとしてあなたはこの世界に何かをもたらすことになります。後世に残すものが意味のあるものとして、人々がそれを認識し、関わり合い、利用できる存在であることが重要です。ですから、構造やテクトニクスはとても重要なのです。それは、建物に価値を与えてくれるのです。

誰もがそう感じるわけではないですが、同意してくれる建築家はたくさんいますよ。それはつまり、建物に超越的な性質を与えるということですが、クライアントにもそうした話をしなくてはいけないのですよね。だから私たちは実現した建築が少ないのでしょうね(笑)

構造が剥き出しになっているような建築は、極端にわかりやすく感じてしまうこともありますし、逆に複雑に感じることもあります。アブ&フォント邸の構造は、それぞれを個別に見ると、すぐには理解できないような空間が作られていますよね。そうした「すぐには理解できない」ことについては、どうお考えですか?

全てを理解することは目的ではないですし、むしろそうすべきではないと私は思っています。重要なことは、一部の要素が他の要素よりも強い意味を持っているということです。私が建築のコンセプトとして構造に興味を持っている理由の一つは、ヒエラルキーが設定できるからです。ゲームのルールと捉えても良いでしょう。

例えば、私たちの設計したフォアウィックのフェリーポート(2015年)は、小さなサービス用の建物なのですが、その主構造と形式的な解決策として、逆さまにしたスティールの円筒形ヴォールトを採用しました。私はそれが正しいと思っていましたし、そうあるべきだと感じていました。それは同時に、技術的な課題や空間的な制約も生み出してしまいましたが、逆さまにしたヴォールトというロジックの中から、二次的な構造やディテールを考えていくことが可能となり、作品にも方向性が生まれてきたわけです。ハンブルク・ハウス(2021)においても同様に、住宅を支える集成材のアーチが設計のルールを決定しています。

つまり、私たちが興味を持っているのは、構造的な思考と素材の論理とのヒエラルキーを注視していくことで、建築がどのような方向性を獲得し得るのか、ということなのです。今日ではどんな形のものでも建てることができるでしょう。しかし、何を基準に決めていけばいいのでしょうか?いや、これが重要なのだと一度決めてしまえば、その選択によってプロジェクトは進んでいくはずです。私たちの場合、この最初の決定が物を作るプロセスに関係してきます。それと重要なことは、論理の破綻を許容しながら、しかしなお追及を続けることです。ヒエラルキーに反抗的な逸脱は、美しい瞬間をもたらすこともあります。私はロードマップが合理的であることに満足感を得ることが多いタイプですが、その過程で非合理的な衝動で、判断してしまうこともあります。いや、それこそが私たちが建築において探求していることですから。

24年6月3日

Beate Hølmebakk: Paraguayans sometimes describe their country as an island surrounded by land. And as though this land is a turbulent sea, it is not so easy to reach the place.

I first saw the Abu & Font house in the O’Neil Ford Duograph 5, edited by Barbara Hoidn and published in 2013 by the University of Texas at Austin. I found the house, which was designed for his mother, remarkably interesting, and decided to reach out personally to Solano Benítez. In the spring of 2016, I travelled to Paraguay with a group of students to visit the house, we also looked at other projects by Gabinete de Arquitecture and by Javier Corvalan. I believe it surprised Solano that we came, but he was very welcoming and generous with his time. Later the same year I invited him to Oslo to present the work of the studio to the whole school.

THE HOUSE IS SPECIAL IN THAT THERE ARE MULTIPLE WAYS TO REACH THE DIFFERENT SPACES. WHAT’S INTERESTING ABOUT BEING ABLE TO MOVE THROUGH A BUILDING IN VARIOUS WAYS?

This is true. I think a house needs to have this quality; to be open and not constrain people’s lives. This house breathes; the ramp is slower than the stairs, the screen in front of it masks your movement; rooms are connected but at different speeds and not all on view. Freedom of movement is a very tangible quality within space.

On the other hand, the appeal, or definite quality, of a dead-end is for me undeniable, and being a gated building; the Abu & Font house also has this quality. Approaching the house from the street, you meet the tall garden wall and the entrance gate– offering a clear threshold. Upon entering, you find yourself in a world of its own, the house occupies almost the entire site, defines its own limit and ends the path you began on.

Ceasing to move, taking in the enclosure, the raised floor of the main space has a strong presence. A large space seems almost compressed between this floor and the fabulous, slightly vaulted, ceramic slab, suspended from the Vierendeel beams. Life in this house unfolds here.

IN TERMS OF MATERIAL, BRICK CLEARLY DOMINATES, HOWEVER THERE ARE ALSO MOVABLE WOODEN ELEMENTS; LIKE THE GARAGE-LIKE DOORS. WHAT IS YOUR SENSE OF THEM?

With their timber structure and heavy chains, these kinetic elements are medieval in expression and operation, adjusting airflow, shade, and protection.

This is a pragmatic, yet magical space, and to me it felt as though the chains of the panels could be made to work with the precision of a Cuckoo-Clock, building towards a climax of the opening or closing of the space. I remember imagining this fictional rhythm in contrast to the fixed mineral construction, like a clock within a stone.

GIVEN EUROPEAN CLIMATIC CONDITIONS ARE VASTLY DIFFERENT, WHAT LESSONS CAN THESE EXOTIC SOUTHERN REFERENCES OFFER NORTHERN ARCHITECTS?

Southern houses offer lessons in the relationship between inside and outside. However, I’ve always appreciated the challenge of building in Northern European climate. Given the external constraints of a cold climate, it’s hard to achieve some of the qualities you’re searching for as an architect, but we tend to think that this difficulty is what gives character to our work. In the main space of the Abu & Font house, the walls are missing, yes, but the central focus is on the interior space itself: the screen, the circulation, the stage-like raised floor. It is a theatrical situation, and maybe that’s something we can learn from and think more about up here in the north: a more performative life facilitated through architecture.

THE STRUCTURAL INVENTION OF THIS HOUSE IS REVEALED IN THE SPACE WHERE PEOPLE GATHER. HOW IMPORTANT IS THE RELATION BETWEEN COLLECTIVE SPACE AND PRIMARY STRUCTURE FOR YOUR OWN PRACTICE?

In the Abu & Font house the presence of structure and how it defines space is beautiful. You really feel that the impressive and original brick structure is made for gathering the family. There is an understanding that a house is a collective space, a place where you share something with others.

This is probably where the center of my interest in this house lies: it’s ethos being defined by the collective nature of families and their well-being. It is without doubt a fascinating project structurally, and it is quite innovative in its use of material, but what I find touching is that these bold gestures are not imposing or making too much of themselves; they simply exist and seem necessary. Consequently, what you feel when you are there is the strong ambition of creating a protected world where Solano’s mother could feel safe, and where the family could gather with her.

Manthey Kula has not realized many projects, but for us, structure has always been deeply connected to the very idea of building. Gabinete de Arquitectura are virtuosos in their use of brick while our work is much simpler, but I believe that the presence of structure is pivotal in terms of space for both practices – otherwise, it’s just not that interesting.

In our case the presence of structure is essential because it helps us understand how things work together. It sets up a relationship with the larger dimensions of the world: gravity, space, time, and other immaterial phenomenon that you want to feel connected to - to make sense of - but often don’t.

In this way buildings where the spatial experience is connected to a structural idea therefore have an almost existential dimension. In Norway, like many places, what’s being built is mostly uninteresting. Most of the people involved in building seem to be more interested in creating photogenic commodities than in contributing to meaningful environments where buildings make sense and interrelate.

Years ago, when I was a student, it was different. Sverre Fehn was one of the professors at the school of architecture in Oslo. He was occupied with the idea of construction. We were taught that there had to be a structural logic ordering the relationship between space and material. Structure was the protagonist, essential and meaningful to both the quality of space and to the sense of life.

I believe this logic is an eternal potential in architecture and talk about this side of practice with my students. Today, when anything is possible, and every form can be given physical presence, if you don’t make sense of what you’re looking at or of that which surrounds you, you become alienated. To feel connected to space and place through a notion of sense is a fundamental visceral human need.

In the Abu & Font house, the structural elements are not decorative; they serve primary purposes. You’ve seen the pictures of the mother’s bedroom, with the steel bracing between the beam and the outer wall? I imagine that the presence of this solitary element must evoke a feeling of comfort.

WHAT CAUSED THE LOSS OF TECTONIC ARCHITECTURE IN NORWAY, EVEN AT THE LEVEL OF ACADEMIA?

There are exceptions, but for the mass construction it is true. I guess what happened was an enormous influx of money. Norway found oil, with oil came wealth and with wealth came the flourishing of real estate development. Clients stopped building for themselves and started building with exit agendas. To say it simple: The focus of the dialogue between clients and architects changed from lasting qualities to quick returns. Buildings should meet mainstream market demands. Architecture became a commodity, and the deep discussion of what architectural quality should or could be disappeared. Risk aversion became a main influence of what was being built. The number of systems and roles that control architects’ work increased dramatically during the last decades. Projects and processes are now rigged to avoid risks and follow standards.

High quality architecture with well-made and interesting tectonic features requires conviction and stubbornness, the safe and easy solution is to do the standard thing, cover it up and get a good photographer to shoot while surfaces are still fresh.

PHILOSOPHICALLY SPEAKING, IF A STRUCTURE HAS ITS OWN AUTONOMOUS, PLASTIC QUALITY, NOTHING ELSE REALLY MATTERS - A BUILDING WITH A COHERENT STRUCTURE IS NOT TIED TO A SPECIFIC PROGRAM AND CAN THUS BECOME SOMETHING ELSE IN THE FUTURE. WHAT DO YOU THINK - HOW WOULD YOU COMMUNICATE THIS INTENTION TO YOUR CLIENTS? IS THIS AMBITION COMPREHENDIBLE?

It is most certainly so! Think about the strange and beautiful brick trusses that support the roof in the basement of the Abu & Font. They give the somewhat indeterminable space a distinct character. The basement was built to accommodate some of the family members. When we visited, ten years after the house’s completion it was the office of Gabinete de Arquitectura.

As an architect, or a builder, you bring something into the world. It is of importance that what you leave behind makes sense and have a presence that those who come after us can perceive, relate to and make use of. This is why structure and tectonics are so important: they give value to the building.

Not everyone feels this way, but I know many architects who do. It’s about giving the buildings transcendental qualities. You must be able to talk to clients about this. Maybe that is why we have built so little (laughs).

AT FIRST GLANCE, EXPOSED STRUCTURE CAN BE EXTREMELY CLEAR OR EVEN RATHER COMPLEX. THE STRUCTURE IN THE ABU & FONT HOUSE CREATES MANY SPACES THAT, SEEN SEPARATELY, ARE NOT IMMEDIATELY UNDERSTANDABLE. WHAT DO YOU THINK ‘NOT UNDERSTANDING EVERYTHING IMMEDIATELY’ BRINGS TO A BUILDING?

Understanding everything isn’t necessarily the goal, quite contrary I believe. What’s important is understanding that some parts are more important than others. One reason I’m interested in structure being part of the main concept of a building is because it sets a hierarchy: You could say it defines the rules of the game.

For example, we designed the Forvik ferry port (2015) with a single inverted steel barrel vault as the main structural and formal solution for a small service building. It felt right, like it had to be that way, but simultaneously it created a series of technical challenges and spatial constraints. Working out the secondary structure and the details within the logic of the upside-down vault, gave the work a sense of direction. The same thing was the case with the House at Hamburgö (2021); the glulam arches that carry the house set the rules for the design.

So, what interests us is how architecture gains orientation through observing hierarchies of structural thought and material logic. Today, you can build almost any form, but what guides you in making decisions? Once you’ve said that one thing is important, the development of the projects can be guided by this choice. In our case this first decision is often connected to how things can be made. What is important to add is that one must allow, or even pursue logical breaks. Insubordinate deviations from the hierarchy may lead to moments of beauty. I often find satisfaction when the roadmap is rational, but when irrational impulses are recognized and implemented along the way. This is what we search for in architecture.

03.06.24

贝亚特·赫尔梅巴克: 巴拉圭人有时将自己的国家形容为一个被陆地包围的岛屿。而这片土地仿佛是波涛汹涌的大海,抵达此地并非易事。

我第一次见到阿布与丰特住宅(Abu & Font House)是在《奥尼尔·福特双联集第五卷》(O'Neil Ford Duograph 5)中。该书由芭芭拉·霍伊登(Barbara Hoidn)编辑,2013年由得克萨斯大学奥斯汀分校出版。这栋索拉诺·贝尼特斯(Solano Benítez)为母亲设计的住宅令我格外着迷,于是我决定亲自联系他。2016年春天,我带着一群学生前往巴拉圭参观这栋房子,同时还考察了建筑工作室(Gabinete de Arquitectura)以及哈维尔·科尔瓦兰(Javier Corvalan)的其他作品。我想我们的到来让索拉诺有些意外,但他非常热情,慷慨地为我们腾出时间。同年晚些时候,我邀请他到奥斯陆向全校展示工作室的作品。

这栋住宅的特殊之处在于,进入不同空间的方式有多种。这种在建筑中“以不同路径穿梭”的体验,其趣味性来自哪里?

确实如此。我认为一栋住宅需要具备这种特质——开放而不束缚人的生活。这栋房子是“会呼吸”的:坡道比楼梯更缓慢,其前方的屏风遮蔽了你的移动轨迹;房间彼此连通,但节奏各异,并非一览无余。行动的自由是空间中一种非常具体的品质。

另一方面,对我来说,“死胡同”的吸引力——或者说某种明确的空间特质——是无法否认的,而作为一栋有门禁的建筑,阿布与丰特住宅也具备这种气质。从街道靠近它时,你会遇见高大的花园围墙和入口门扉——形成一道清晰的界限。一旦进入,便发现自己置身于一个独立的世界:住宅几乎占据了整个场地,划定自身的边缘,终结了你来时的路径。

停下脚步环顾四周,主空间抬高的地面存在感尤为强烈。这片广阔的区域仿佛被压缩在这层地面与悬浮于空腹梁(Vierendeel beams)之下的微拱形陶板之间。这座住宅的生活场景在此徐徐展开。

就材料而言,砖无疑是主导元素,但也有可移动的木构件——比如车库门。您如何看待它们?

这些带有木结构和沉重链条的动态构件,无论形态还是操作方式都透着一股中世纪气息,用于调节气流、遮阳与防护。

这是一个实用却充满魔力的空间。对我而言,墙板的链条仿佛可以像布谷鸟钟般精密运作,将空间的开启或闭合推向某种仪式性的高潮。我仍记得自己曾想象这种虚构的节奏——它与固定的矿物结构形成对比,如同石头内部嵌着一座时钟。

考虑到欧洲气候条件差异巨大,这些来自南半球的异域经验能为北方建筑师提供什么启示?

南方的住宅教会我们思考内外关系。不过,我一直欣赏北欧气候下的建造挑战。寒冷气候的外部限制让我们难以实现某些建筑师追求的特质,但正因这种困难,我们的作品反而获得了独特个性。在阿布与丰特住宅的主空间中,墙体虽被消解,但核心聚焦于内部空间本身:屏风、动线与舞台般的抬升地面。这是一种戏剧化的场景营造——或许我们北方建筑师可以从中学习,更多地思考如何通过建筑促成一种更具“表演性”的生活。

这座住宅的结构创新体现在人们聚集的空间中。对您而言,公共空间与主体结构的关联有多重要?

阿布与丰特住宅中结构的在场感及其对空间的界定方式非常美妙。你能真切感受到,这座令人惊叹的原始砖构筑物是为家族团聚而设计的。它传递了一种理念:住宅是集体空间,是与他人共享的场所。

这或许正是我对这座住宅最感兴趣的核心:其精神由家族的集体性与福祉所定义。从结构上看,它无疑是迷人的项目,材料运用也颇具创新性。但最触动我的是,这些大胆的手法并未显得强势或过度张扬;它们只是存在,且仿佛理应存在。因此,当你置身其中时,感受到的是一种强烈的抱负——创造一个受庇护的世界,让索拉诺的母亲感到安全,让家族得以围绕她团聚。

曼泰·库拉(Manthey Kula)事务所完成的作品虽不多,但对我们而言,结构始终与建造的本质紧密相连。Gabinete de Arquitectura是运用砖材的大师,而我们的作品更为朴素。但我相信,结构的在场感对两种实践的空间塑造都至关重要——否则建筑将失去趣味。

在我们的实践中,结构的显性至关重要,因为它帮助我们理解事物如何协同运作。它建立起与更宏大维度世界的联系:重力、空间、时间,以及那些你想要感知却难以捉摸的无形现象。

因此,当空间体验与结构理念相连时,建筑便获得了近乎存在主义的维度。在挪威,正如许多地方一样,当下的建造大多乏善可陈。多数从业者似乎更热衷于打造“上镜商品”,而非创造建筑之间相互关联、富有意义的场所。

多年前我求学时,情况截然不同。斯维勒·费恩(Sverre Fehn)曾是奥斯陆建筑学院的教授之一。他执着于建造的本质。我们被教导必须用结构逻辑统摄空间与材料的关系。结构是主角,对空间品质与生命感知皆不可或缺。

我相信这种逻辑是建筑永恒的潜能,并常与学生探讨实践的这层维度。如今,当一切形式皆可实现,若无法让人理解所见之物与所处环境,人便会感到疏离。通过“意义感”与空间场所建立联系,是人类根深蒂固的本能需求。

在阿布与丰特住宅中,结构元素绝非装饰,它们承担着核心功能。你见过那间母亲卧室的照片吗?梁与外墙之间的钢制支撑仿佛孤独的卫士,其存在本身便传递着令人安心的力量。

为何挪威的建构建筑传统日渐式微,甚至在学术界亦然?

虽有个例,但批量建造确实如此。我想根源在于资本洪流。挪威发现石油后,财富催生了房地产繁荣。业主不再为自己建造,而是带着退出策略投资房产。简言之,业主与建筑师对话的重心从永恒品质转向快速回报。建筑需迎合主流市场需求,沦为商品,关于建筑本质的深度讨论随之消失。风险规避成为主导,过去几十年间,管控建筑师工作的体系与角色激增,项目流程被设计成规避风险、遵循标准的流水线。

具备精妙建构特征的高品质建筑需要信念与固执,而安全省力的做法是套用标准方案、掩盖本质,再找优秀摄影师在表面光鲜时拍摄。

从哲学角度,若结构具备自主的可塑性,其他皆可让步——结构连贯的建筑不必绑定特定功能,未来可化身他物。您如何向客户传达这种理念?这类抱负能被理解吗?

当然可以!想想阿布与丰特地窖中那些奇异而美丽的砖砌桁架,它们赋予了这个模糊空间独特的性格。地窖原为家族成员设计,十年后我们探访时,这里已成为Gabinete de Arquitectura的办公室。

作为建筑师或建造者,你为世界增添事物。重要的是,你留下的作品需具备可被后人感知、关联并使用的在场感。这正是结构与建构如此重要的原因:它们赋予建筑价值。

并非所有人都认同这点,但我知道许多建筑师心有共鸣。这是关于赋予建筑超越性的品质。你必须能与客户谈论这些——也许这正是我们建成作品寥寥无几的原因(笑)。

外露结构初看可能极其清晰,也可能相当复杂。阿布与丰特住宅的结构创造了诸多乍看费解的空间。您认为“无法即刻理解一切”为建筑带来了什么?

理解一切绝非目标,恰恰相反。重要的是认识到某些部分比其他部分更关键。我对结构成为建筑核心理念感兴趣的原因之一,是它确立了层级——可以说,它定义了游戏的规则。

例如,我们设计的福尔维克轮渡码头(2015)以一樘倒置钢制筒拱作为服务建筑的主结构与形态方案。这方案直觉上正确,却也带来技术挑战与空间限制。在倒置拱逻辑下推敲次级结构与细部,为作品赋予了方向感。汉堡岛住宅(2021)亦如此:胶合木拱架设定了设计规则。

我们关注的是建筑如何通过结构思维层级与材料逻辑获得方向性。如今你几乎可以建造任何形态,但决策的依据是什么?一旦确定某要素至关重要,项目发展便可由此引导。对我们而言,这初始决定常与“如何实现”相关。需补充的是,必须允许甚至追求逻辑断裂——对层级的叛逆偏离可能催生美的瞬间。当路线理性而过程中接纳非理性冲动时,我常感到满足。这正是我们在建筑中追寻的。

24年6月3日

ベアテ・ホルムバック:パラグアイの人は、自国のことを「陸に囲まれた島」だと表現するそうですね。荒れ狂う海のように簡単にはたどり着けないのだと。

アブ&フォント邸を初めて目にしたのは、バーバラ・ホイドンが編集を手がけた、テキサス大学オースティン校出版の『O’Neil Ford Duograph 5』という本でした。その家は、ソラーノ・ベニテスが彼の母親のために建てた家です。とても興味を惹かれたので、彼に直接連絡を取ってみたのです。そして2016年の春、学生たちを連れてパラグアイへ向かい、その家を訪問したのです。ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラやハビエル・コルヴァランの手がけたプロジェクトも見学しました。私たちが訪ねてきたことに彼は驚いていたようですが、時間を割いて快く歓迎してくれました。同じ年の暮れのこと、今度は彼をオスロへ招待して、私たちの大学内で作品のレクチャーをお願いしました。

この家には、さまざまな空間がありますが、それぞれの空間へのアプローチが一つではなく複数用意されている点が特徴ですよね。このように建物内を移動できることの面白さは、どういったところにあるのでしょうか?

そうですね。家というものはそのように開放的で、人々の生活を制限しないことが必要だと思います。この家に設けられたスロープの場合、人は階段よりもゆっくりと進みますね。ですが、人の動きはスロープの手前に設けられたスクリーンで隠されています。部屋同士は、つながりつつも全てが同時に見渡せるわけではありません。それぞれに流れている時間のスピードが異なっているのです。家が呼吸している、と言えますか。自由に移動できるということは、空間を考える上でも非常に触覚的で具体的な性質の一つだと思います。

一方で、行き止まりの空間が持つ確固たる魅力も否定できません。門によって閉ざされているという意味で、このアブ&フォント邸も行き止まりの建築なのです。通りからこの家へと向かっていくと、背の高い中庭の壁、そしてエントランスの門が見えてきます。そこには明確な境界線が作られています。そして、中へ入るとそこがまるで別空間のように感じます。敷地全体が家となっているのです。つまりは、今まさに始まったはずの建物へのアプローチもそこで終わってしまうのです。

歩みを止め、その囲われた空間を見渡してみます。メインスペースとなる空間の床は、地面から持ち上げられていて、強い存在感が感じられます。フィーレンディールトラスから吊り上げられたセラミックのスラブ天井は素晴らしいものですよね。その緩くカーブした天井と、持ち上げられた床との間の空間には、上下からの圧縮力が働いているように感じられます。まさに、ここで生活が展開されるのです。

使用されている素材に関しては、レンガが多いですよね。ガレージのドアのような可動式の木の素材も気になりますが、素材に関してはどうお考えですか。

木のパネルと重いチェーンによって、空気の流れを変えたり、日差しを遮ることもできるわけですが、中世的なギミックと表現ですよね。

実用性によるものですが、魔術的な空間の魅力を感じます。私には、その木のパネルに取り付けられたチェーンが、まるで鳩時計のように正確に動き出し、内部の空間を閉じたり、開いたりして、クライマックスを演出する建物の姿が想像できるのです。鉱物のように動かないはずの建築とは対照的なこのフィクショナルなリズムは、石の中の時計、のイメージとでも例えられるでしょうか。

パラグアイは、ヨーロッパの気候条件とは大きく異なりますよね。そうした南方のエキゾチズムは、北方の建築家にとってどのように受け止められるのでしょうか?

内部と外部の関係に関しては得るものが多いですね。ですが、北欧のような気候の中で建築を作る難しさにも感謝しているのです。寒冷地であるという外的な制約がありますから、建築家として探求したいことの全てを実現することは難しくなります。ですが、だからこそ作品が個性的なものになるのだと思います。アブ&フォント邸のメインスペースには確かに壁が存在していません。内部空間そのものがそこにはあるのでしょう。スロープのスクリーンや回遊導線、そして舞台のように高く上げられた床。演劇的なシチュエーション。そう、これこそが私たち北方の人間が学び、考えるべきことなのでしょう。建築を通して実現されたパフォーマンス性の高い生活の姿です。

この家では、その構造的な発明が家族の集まるリビング空間に現れています。主構造と空間との関係についてはどうお考えですか?

アブ&フォント邸においては、構造体の存在自体もそうですが、構造が空間を形づくるその方法自体が美しいですね。強烈で独創的なレンガの構造体が、実は家族の集う空間のために選ばれたものであると気づくでしょう。家は誰かと集まるための空間であり、何かを共有する場所であるべきだという意識が感じられます。

私がこの家に興味を持っているのはおそらく、そこにエートスを感じるからでしょう。それは、家族が集まり幸福を感じることによって作られるものです。もちろん家の構造的なアイデアは魅力的ですし、素材の使い方も斬新なものだと思います。ですが、私の感動はそうした大胆な試みが、押しつけがましく主張していないことにあるのだと思います。ただ必要だから、そこにあるといったように。結果的に、ソラーノさんの母親が安心して過ごし、家族が集る安心した世界をつくりだそうとする意思が感じられます。

私たちマンタイ・クラは、これまでに実現したプロジェクトは多くありません。ですが、私たちにとって構造というものは常に建物のアイデアと深く結びついているものです。ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラはレンガ使いの名人ですよね。それに比べて私たちはもっとシンプルな方法ではありますが、どちらの事務所にとっても、構造の存在は空間を考える上で極めて重要だと思います。そうでなければ面白くありません。

私たちの場合、構造の存在は不可欠です。構造は、物事の相互関係を理解させてくれるものです。世界のより大きな次元との関係を構築する存在、例えば、重力、空間、時間、あるいは、近づきたくても近づけない、見たくても見ることのできない、そうした無形の現象と関係を結ぶきっかけとなる存在なのです。

空間体験と構造的なアイデアとが結びついた建物には、実存的な感覚が宿るのだと思います。世界の他の地域と同じように、ノルウェーのほとんどの建築物は面白くありません。たいていの人は、写真映えする商品としての建築に興味を持ったとしても、それが環境に対していかに有意義な相互作用をもたらすかといったことには興味がないのです。

大昔の話になりますが、私が学生だったころは違いました。オスロの建築大学の教授の一人にスヴェレ・フェーンという人がいました。彼は、コンストラクションという概念に取り憑かれていました。そこで私たちは空間と素材を関係づけるには構造的なロジックが必要であることを教えられました。構造は建築の主人公として、空間の質と生活の質、その両方に必要とされるものなのです。

私はこのロジックにこそ、建築における永遠の可能性を信じていますし、実務的な側面からそう学生に伝えています。あらゆることが可能になり、あらゆる形が物理的に作り得る今日です。私たちは一体何を見て、何に囲まれているのか、そうしたことを考え理解していなければ、世界から阻害されていくように感じます。自身の感覚を通じて、空間や場所とつながることは、人間の根源的な欲求なのでしょう。

アブ&フォント邸では、構造は装飾的なものではなく、構造としての本来の目的を果たしています。母親の寝室の写真をご覧になりましたか?梁と外壁との間に鉄の補強が見えるでしょう。こうした仲間外れの要素も、空間に心地よさを作り出す要因なのかもしれませんよね。

ノルウェーのアカデミックな建築の世界においても、こうしたテクトニクスを重視した建築は減ってきているようですが、その原因はどこにあるのでしょうか?

BH: 例外もありますが、大量生産される建築に関しては、全くその通りだと思います。莫大な資金が流入したからでしょう。ノルウェーは石油を発掘したのですが、石油は富をもたらしますよね。それで不動産も発展したのでしょう。クライアントは自分自身のために建築を考えなくなり、むしろその出口戦略を考え始めます。要は、クライアントと建築家との対話が、永続的なものから短期的に回収できるものへと変化したのです。建物は市場の需要を満たす必要がありますから、建築は商品となり下がってしまい、その質について深く議論されることがなくなりました。リスク回避の考え方も、建設に大きな影響を与える要因です。過去数十年の間に、建築家の仕事を管理するシステムや役割は劇的に増加しましたし、プロジェクトやそのプロセスは、リスクを回避するために標準的であることを強いられるのです。

高い質を担保しながら、テクトニクス的にも面白い建築を作ろうとするならば、頑なに信念を貫き通す必要があります。いや、安全でかつ簡単な解決策もありますが。標準的な仕様に従いながら、うまくそれらを隠蔽し、表面がまだ綺麗なうちに腕の良いカメラマンに撮影してもらえば良いのです。

やや哲学的な問いになってしまいますが、建物の構造自体に自律性や可塑性が担保されていさえすれば、実はそれだけで十分なのではないでしょうか。つまり、そうした構造を持つ建物は、特定のプログラムに縛られることなく、将来的に別の用途の建物に変更することができるのではないでしょうか。どうでしょうか。そうした問いかけをクライアントにもされたりしますか?こうした建築家の野心は理解され得るものでしょうか?

ほとんどの建築は本当にそうですよね!アブ&フォント邸の地下には、屋根を支える奇妙な、しかし美しいレンガのトラスがありますよね。いくぶん曖昧な空間なのですが、そのトラスのおかげで空間が引き締まっているように感じます。その地下空間は、家族の誰かが使う予定で作られたものなのですが、私たちが訪れた時には、すでに竣工から10年が経っていて、ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラの事務所として使われていました。

建築家として、あるいはビルダーとしてあなたはこの世界に何かをもたらすことになります。後世に残すものが意味のあるものとして、人々がそれを認識し、関わり合い、利用できる存在であることが重要です。ですから、構造やテクトニクスはとても重要なのです。それは、建物に価値を与えてくれるのです。

誰もがそう感じるわけではないですが、同意してくれる建築家はたくさんいますよ。それはつまり、建物に超越的な性質を与えるということですが、クライアントにもそうした話をしなくてはいけないのですよね。だから私たちは実現した建築が少ないのでしょうね(笑)

構造が剥き出しになっているような建築は、極端にわかりやすく感じてしまうこともありますし、逆に複雑に感じることもあります。アブ&フォント邸の構造は、それぞれを個別に見ると、すぐには理解できないような空間が作られていますよね。そうした「すぐには理解できない」ことについては、どうお考えですか?

全てを理解することは目的ではないですし、むしろそうすべきではないと私は思っています。重要なことは、一部の要素が他の要素よりも強い意味を持っているということです。私が建築のコンセプトとして構造に興味を持っている理由の一つは、ヒエラルキーが設定できるからです。ゲームのルールと捉えても良いでしょう。

例えば、私たちの設計したフォアウィックのフェリーポート(2015年)は、小さなサービス用の建物なのですが、その主構造と形式的な解決策として、逆さまにしたスティールの円筒形ヴォールトを採用しました。私はそれが正しいと思っていましたし、そうあるべきだと感じていました。それは同時に、技術的な課題や空間的な制約も生み出してしまいましたが、逆さまにしたヴォールトというロジックの中から、二次的な構造やディテールを考えていくことが可能となり、作品にも方向性が生まれてきたわけです。ハンブルク・ハウス(2021)においても同様に、住宅を支える集成材のアーチが設計のルールを決定しています。

つまり、私たちが興味を持っているのは、構造的な思考と素材の論理とのヒエラルキーを注視していくことで、建築がどのような方向性を獲得し得るのか、ということなのです。今日ではどんな形のものでも建てることができるでしょう。しかし、何を基準に決めていけばいいのでしょうか?いや、これが重要なのだと一度決めてしまえば、その選択によってプロジェクトは進んでいくはずです。私たちの場合、この最初の決定が物を作るプロセスに関係してきます。それと重要なことは、論理の破綻を許容しながら、しかしなお追及を続けることです。ヒエラルキーに反抗的な逸脱は、美しい瞬間をもたらすこともあります。私はロードマップが合理的であることに満足感を得ることが多いタイプですが、その過程で非合理的な衝動で、判断してしまうこともあります。いや、それこそが私たちが建築において探求していることですから。

24年6月3日

Beate Hølmebakk: Paraguayans sometimes describe their country as an island surrounded by land. And as though this land is a turbulent sea, it is not so easy to reach the place.

I first saw the Abu & Font house in the O’Neil Ford Duograph 5, edited by Barbara Hoidn and published in 2013 by the University of Texas at Austin. I found the house, which was designed for his mother, remarkably interesting, and decided to reach out personally to Solano Benítez. In the spring of 2016, I travelled to Paraguay with a group of students to visit the house, we also looked at other projects by Gabinete de Arquitecture and by Javier Corvalan. I believe it surprised Solano that we came, but he was very welcoming and generous with his time. Later the same year I invited him to Oslo to present the work of the studio to the whole school.

THE HOUSE IS SPECIAL IN THAT THERE ARE MULTIPLE WAYS TO REACH THE DIFFERENT SPACES. WHAT’S INTERESTING ABOUT BEING ABLE TO MOVE THROUGH A BUILDING IN VARIOUS WAYS?

This is true. I think a house needs to have this quality; to be open and not constrain people’s lives. This house breathes; the ramp is slower than the stairs, the screen in front of it masks your movement; rooms are connected but at different speeds and not all on view. Freedom of movement is a very tangible quality within space.

On the other hand, the appeal, or definite quality, of a dead-end is for me undeniable, and being a gated building; the Abu & Font house also has this quality. Approaching the house from the street, you meet the tall garden wall and the entrance gate– offering a clear threshold. Upon entering, you find yourself in a world of its own, the house occupies almost the entire site, defines its own limit and ends the path you began on.

Ceasing to move, taking in the enclosure, the raised floor of the main space has a strong presence. A large space seems almost compressed between this floor and the fabulous, slightly vaulted, ceramic slab, suspended from the Vierendeel beams. Life in this house unfolds here.

IN TERMS OF MATERIAL, BRICK CLEARLY DOMINATES, HOWEVER THERE ARE ALSO MOVABLE WOODEN ELEMENTS; LIKE THE GARAGE-LIKE DOORS. WHAT IS YOUR SENSE OF THEM?

With their timber structure and heavy chains, these kinetic elements are medieval in expression and operation, adjusting airflow, shade, and protection.

This is a pragmatic, yet magical space, and to me it felt as though the chains of the panels could be made to work with the precision of a Cuckoo-Clock, building towards a climax of the opening or closing of the space. I remember imagining this fictional rhythm in contrast to the fixed mineral construction, like a clock within a stone.

GIVEN EUROPEAN CLIMATIC CONDITIONS ARE VASTLY DIFFERENT, WHAT LESSONS CAN THESE EXOTIC SOUTHERN REFERENCES OFFER NORTHERN ARCHITECTS?

Southern houses offer lessons in the relationship between inside and outside. However, I’ve always appreciated the challenge of building in Northern European climate. Given the external constraints of a cold climate, it’s hard to achieve some of the qualities you’re searching for as an architect, but we tend to think that this difficulty is what gives character to our work. In the main space of the Abu & Font house, the walls are missing, yes, but the central focus is on the interior space itself: the screen, the circulation, the stage-like raised floor. It is a theatrical situation, and maybe that’s something we can learn from and think more about up here in the north: a more performative life facilitated through architecture.

THE STRUCTURAL INVENTION OF THIS HOUSE IS REVEALED IN THE SPACE WHERE PEOPLE GATHER. HOW IMPORTANT IS THE RELATION BETWEEN COLLECTIVE SPACE AND PRIMARY STRUCTURE FOR YOUR OWN PRACTICE?

In the Abu & Font house the presence of structure and how it defines space is beautiful. You really feel that the impressive and original brick structure is made for gathering the family. There is an understanding that a house is a collective space, a place where you share something with others.

This is probably where the center of my interest in this house lies: it’s ethos being defined by the collective nature of families and their well-being. It is without doubt a fascinating project structurally, and it is quite innovative in its use of material, but what I find touching is that these bold gestures are not imposing or making too much of themselves; they simply exist and seem necessary. Consequently, what you feel when you are there is the strong ambition of creating a protected world where Solano’s mother could feel safe, and where the family could gather with her.

Manthey Kula has not realized many projects, but for us, structure has always been deeply connected to the very idea of building. Gabinete de Arquitectura are virtuosos in their use of brick while our work is much simpler, but I believe that the presence of structure is pivotal in terms of space for both practices – otherwise, it’s just not that interesting.

In our case the presence of structure is essential because it helps us understand how things work together. It sets up a relationship with the larger dimensions of the world: gravity, space, time, and other immaterial phenomenon that you want to feel connected to - to make sense of - but often don’t.

In this way buildings where the spatial experience is connected to a structural idea therefore have an almost existential dimension. In Norway, like many places, what’s being built is mostly uninteresting. Most of the people involved in building seem to be more interested in creating photogenic commodities than in contributing to meaningful environments where buildings make sense and interrelate.

Years ago, when I was a student, it was different. Sverre Fehn was one of the professors at the school of architecture in Oslo. He was occupied with the idea of construction. We were taught that there had to be a structural logic ordering the relationship between space and material. Structure was the protagonist, essential and meaningful to both the quality of space and to the sense of life.

I believe this logic is an eternal potential in architecture and talk about this side of practice with my students. Today, when anything is possible, and every form can be given physical presence, if you don’t make sense of what you’re looking at or of that which surrounds you, you become alienated. To feel connected to space and place through a notion of sense is a fundamental visceral human need.

In the Abu & Font house, the structural elements are not decorative; they serve primary purposes. You’ve seen the pictures of the mother’s bedroom, with the steel bracing between the beam and the outer wall? I imagine that the presence of this solitary element must evoke a feeling of comfort.

WHAT CAUSED THE LOSS OF TECTONIC ARCHITECTURE IN NORWAY, EVEN AT THE LEVEL OF ACADEMIA?

There are exceptions, but for the mass construction it is true. I guess what happened was an enormous influx of money. Norway found oil, with oil came wealth and with wealth came the flourishing of real estate development. Clients stopped building for themselves and started building with exit agendas. To say it simple: The focus of the dialogue between clients and architects changed from lasting qualities to quick returns. Buildings should meet mainstream market demands. Architecture became a commodity, and the deep discussion of what architectural quality should or could be disappeared. Risk aversion became a main influence of what was being built. The number of systems and roles that control architects’ work increased dramatically during the last decades. Projects and processes are now rigged to avoid risks and follow standards.

High quality architecture with well-made and interesting tectonic features requires conviction and stubbornness, the safe and easy solution is to do the standard thing, cover it up and get a good photographer to shoot while surfaces are still fresh.

PHILOSOPHICALLY SPEAKING, IF A STRUCTURE HAS ITS OWN AUTONOMOUS, PLASTIC QUALITY, NOTHING ELSE REALLY MATTERS - A BUILDING WITH A COHERENT STRUCTURE IS NOT TIED TO A SPECIFIC PROGRAM AND CAN THUS BECOME SOMETHING ELSE IN THE FUTURE. WHAT DO YOU THINK - HOW WOULD YOU COMMUNICATE THIS INTENTION TO YOUR CLIENTS? IS THIS AMBITION COMPREHENDIBLE?

It is most certainly so! Think about the strange and beautiful brick trusses that support the roof in the basement of the Abu & Font. They give the somewhat indeterminable space a distinct character. The basement was built to accommodate some of the family members. When we visited, ten years after the house’s completion it was the office of Gabinete de Arquitectura.

As an architect, or a builder, you bring something into the world. It is of importance that what you leave behind makes sense and have a presence that those who come after us can perceive, relate to and make use of. This is why structure and tectonics are so important: they give value to the building.

Not everyone feels this way, but I know many architects who do. It’s about giving the buildings transcendental qualities. You must be able to talk to clients about this. Maybe that is why we have built so little (laughs).

AT FIRST GLANCE, EXPOSED STRUCTURE CAN BE EXTREMELY CLEAR OR EVEN RATHER COMPLEX. THE STRUCTURE IN THE ABU & FONT HOUSE CREATES MANY SPACES THAT, SEEN SEPARATELY, ARE NOT IMMEDIATELY UNDERSTANDABLE. WHAT DO YOU THINK ‘NOT UNDERSTANDING EVERYTHING IMMEDIATELY’ BRINGS TO A BUILDING?

Understanding everything isn’t necessarily the goal, quite contrary I believe. What’s important is understanding that some parts are more important than others. One reason I’m interested in structure being part of the main concept of a building is because it sets a hierarchy: You could say it defines the rules of the game.

For example, we designed the Forvik ferry port (2015) with a single inverted steel barrel vault as the main structural and formal solution for a small service building. It felt right, like it had to be that way, but simultaneously it created a series of technical challenges and spatial constraints. Working out the secondary structure and the details within the logic of the upside-down vault, gave the work a sense of direction. The same thing was the case with the House at Hamburgö (2021); the glulam arches that carry the house set the rules for the design.

So, what interests us is how architecture gains orientation through observing hierarchies of structural thought and material logic. Today, you can build almost any form, but what guides you in making decisions? Once you’ve said that one thing is important, the development of the projects can be guided by this choice. In our case this first decision is often connected to how things can be made. What is important to add is that one must allow, or even pursue logical breaks. Insubordinate deviations from the hierarchy may lead to moments of beauty. I often find satisfaction when the roadmap is rational, but when irrational impulses are recognized and implemented along the way. This is what we search for in architecture.

03.06.24

贝亚特·赫尔梅巴克: 巴拉圭人有时将自己的国家形容为一个被陆地包围的岛屿。而这片土地仿佛是波涛汹涌的大海,抵达此地并非易事。

我第一次见到阿布与丰特住宅(Abu & Font House)是在《奥尼尔·福特双联集第五卷》(O'Neil Ford Duograph 5)中。该书由芭芭拉·霍伊登(Barbara Hoidn)编辑,2013年由得克萨斯大学奥斯汀分校出版。这栋索拉诺·贝尼特斯(Solano Benítez)为母亲设计的住宅令我格外着迷,于是我决定亲自联系他。2016年春天,我带着一群学生前往巴拉圭参观这栋房子,同时还考察了建筑工作室(Gabinete de Arquitectura)以及哈维尔·科尔瓦兰(Javier Corvalan)的其他作品。我想我们的到来让索拉诺有些意外,但他非常热情,慷慨地为我们腾出时间。同年晚些时候,我邀请他到奥斯陆向全校展示工作室的作品。

这栋住宅的特殊之处在于,进入不同空间的方式有多种。这种在建筑中“以不同路径穿梭”的体验,其趣味性来自哪里?

确实如此。我认为一栋住宅需要具备这种特质——开放而不束缚人的生活。这栋房子是“会呼吸”的:坡道比楼梯更缓慢,其前方的屏风遮蔽了你的移动轨迹;房间彼此连通,但节奏各异,并非一览无余。行动的自由是空间中一种非常具体的品质。

另一方面,对我来说,“死胡同”的吸引力——或者说某种明确的空间特质——是无法否认的,而作为一栋有门禁的建筑,阿布与丰特住宅也具备这种气质。从街道靠近它时,你会遇见高大的花园围墙和入口门扉——形成一道清晰的界限。一旦进入,便发现自己置身于一个独立的世界:住宅几乎占据了整个场地,划定自身的边缘,终结了你来时的路径。

停下脚步环顾四周,主空间抬高的地面存在感尤为强烈。这片广阔的区域仿佛被压缩在这层地面与悬浮于空腹梁(Vierendeel beams)之下的微拱形陶板之间。这座住宅的生活场景在此徐徐展开。

就材料而言,砖无疑是主导元素,但也有可移动的木构件——比如车库门。您如何看待它们?

这些带有木结构和沉重链条的动态构件,无论形态还是操作方式都透着一股中世纪气息,用于调节气流、遮阳与防护。

这是一个实用却充满魔力的空间。对我而言,墙板的链条仿佛可以像布谷鸟钟般精密运作,将空间的开启或闭合推向某种仪式性的高潮。我仍记得自己曾想象这种虚构的节奏——它与固定的矿物结构形成对比,如同石头内部嵌着一座时钟。

考虑到欧洲气候条件差异巨大,这些来自南半球的异域经验能为北方建筑师提供什么启示?

南方的住宅教会我们思考内外关系。不过,我一直欣赏北欧气候下的建造挑战。寒冷气候的外部限制让我们难以实现某些建筑师追求的特质,但正因这种困难,我们的作品反而获得了独特个性。在阿布与丰特住宅的主空间中,墙体虽被消解,但核心聚焦于内部空间本身:屏风、动线与舞台般的抬升地面。这是一种戏剧化的场景营造——或许我们北方建筑师可以从中学习,更多地思考如何通过建筑促成一种更具“表演性”的生活。

这座住宅的结构创新体现在人们聚集的空间中。对您而言,公共空间与主体结构的关联有多重要?

阿布与丰特住宅中结构的在场感及其对空间的界定方式非常美妙。你能真切感受到,这座令人惊叹的原始砖构筑物是为家族团聚而设计的。它传递了一种理念:住宅是集体空间,是与他人共享的场所。

这或许正是我对这座住宅最感兴趣的核心:其精神由家族的集体性与福祉所定义。从结构上看,它无疑是迷人的项目,材料运用也颇具创新性。但最触动我的是,这些大胆的手法并未显得强势或过度张扬;它们只是存在,且仿佛理应存在。因此,当你置身其中时,感受到的是一种强烈的抱负——创造一个受庇护的世界,让索拉诺的母亲感到安全,让家族得以围绕她团聚。

曼泰·库拉(Manthey Kula)事务所完成的作品虽不多,但对我们而言,结构始终与建造的本质紧密相连。Gabinete de Arquitectura是运用砖材的大师,而我们的作品更为朴素。但我相信,结构的在场感对两种实践的空间塑造都至关重要——否则建筑将失去趣味。

在我们的实践中,结构的显性至关重要,因为它帮助我们理解事物如何协同运作。它建立起与更宏大维度世界的联系:重力、空间、时间,以及那些你想要感知却难以捉摸的无形现象。

因此,当空间体验与结构理念相连时,建筑便获得了近乎存在主义的维度。在挪威,正如许多地方一样,当下的建造大多乏善可陈。多数从业者似乎更热衷于打造“上镜商品”,而非创造建筑之间相互关联、富有意义的场所。

多年前我求学时,情况截然不同。斯维勒·费恩(Sverre Fehn)曾是奥斯陆建筑学院的教授之一。他执着于建造的本质。我们被教导必须用结构逻辑统摄空间与材料的关系。结构是主角,对空间品质与生命感知皆不可或缺。

我相信这种逻辑是建筑永恒的潜能,并常与学生探讨实践的这层维度。如今,当一切形式皆可实现,若无法让人理解所见之物与所处环境,人便会感到疏离。通过“意义感”与空间场所建立联系,是人类根深蒂固的本能需求。

在阿布与丰特住宅中,结构元素绝非装饰,它们承担着核心功能。你见过那间母亲卧室的照片吗?梁与外墙之间的钢制支撑仿佛孤独的卫士,其存在本身便传递着令人安心的力量。

为何挪威的建构建筑传统日渐式微,甚至在学术界亦然?

虽有个例,但批量建造确实如此。我想根源在于资本洪流。挪威发现石油后,财富催生了房地产繁荣。业主不再为自己建造,而是带着退出策略投资房产。简言之,业主与建筑师对话的重心从永恒品质转向快速回报。建筑需迎合主流市场需求,沦为商品,关于建筑本质的深度讨论随之消失。风险规避成为主导,过去几十年间,管控建筑师工作的体系与角色激增,项目流程被设计成规避风险、遵循标准的流水线。

具备精妙建构特征的高品质建筑需要信念与固执,而安全省力的做法是套用标准方案、掩盖本质,再找优秀摄影师在表面光鲜时拍摄。

从哲学角度,若结构具备自主的可塑性,其他皆可让步——结构连贯的建筑不必绑定特定功能,未来可化身他物。您如何向客户传达这种理念?这类抱负能被理解吗?

当然可以!想想阿布与丰特地窖中那些奇异而美丽的砖砌桁架,它们赋予了这个模糊空间独特的性格。地窖原为家族成员设计,十年后我们探访时,这里已成为Gabinete de Arquitectura的办公室。

作为建筑师或建造者,你为世界增添事物。重要的是,你留下的作品需具备可被后人感知、关联并使用的在场感。这正是结构与建构如此重要的原因:它们赋予建筑价值。

并非所有人都认同这点,但我知道许多建筑师心有共鸣。这是关于赋予建筑超越性的品质。你必须能与客户谈论这些——也许这正是我们建成作品寥寥无几的原因(笑)。

外露结构初看可能极其清晰,也可能相当复杂。阿布与丰特住宅的结构创造了诸多乍看费解的空间。您认为“无法即刻理解一切”为建筑带来了什么?

理解一切绝非目标,恰恰相反。重要的是认识到某些部分比其他部分更关键。我对结构成为建筑核心理念感兴趣的原因之一,是它确立了层级——可以说,它定义了游戏的规则。

例如,我们设计的福尔维克轮渡码头(2015)以一樘倒置钢制筒拱作为服务建筑的主结构与形态方案。这方案直觉上正确,却也带来技术挑战与空间限制。在倒置拱逻辑下推敲次级结构与细部,为作品赋予了方向感。汉堡岛住宅(2021)亦如此:胶合木拱架设定了设计规则。

我们关注的是建筑如何通过结构思维层级与材料逻辑获得方向性。如今你几乎可以建造任何形态,但决策的依据是什么?一旦确定某要素至关重要,项目发展便可由此引导。对我们而言,这初始决定常与“如何实现”相关。需补充的是,必须允许甚至追求逻辑断裂——对层级的叛逆偏离可能催生美的瞬间。当路线理性而过程中接纳非理性冲动时,我常感到满足。这正是我们在建筑中追寻的。

24年6月3日

ベアテ・ホルムバック:パラグアイの人は、自国のことを「陸に囲まれた島」だと表現するそうですね。荒れ狂う海のように簡単にはたどり着けないのだと。

アブ&フォント邸を初めて目にしたのは、バーバラ・ホイドンが編集を手がけた、テキサス大学オースティン校出版の『O’Neil Ford Duograph 5』という本でした。その家は、ソラーノ・ベニテスが彼の母親のために建てた家です。とても興味を惹かれたので、彼に直接連絡を取ってみたのです。そして2016年の春、学生たちを連れてパラグアイへ向かい、その家を訪問したのです。ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラやハビエル・コルヴァランの手がけたプロジェクトも見学しました。私たちが訪ねてきたことに彼は驚いていたようですが、時間を割いて快く歓迎してくれました。同じ年の暮れのこと、今度は彼をオスロへ招待して、私たちの大学内で作品のレクチャーをお願いしました。

この家には、さまざまな空間がありますが、それぞれの空間へのアプローチが一つではなく複数用意されている点が特徴ですよね。このように建物内を移動できることの面白さは、どういったところにあるのでしょうか?

そうですね。家というものはそのように開放的で、人々の生活を制限しないことが必要だと思います。この家に設けられたスロープの場合、人は階段よりもゆっくりと進みますね。ですが、人の動きはスロープの手前に設けられたスクリーンで隠されています。部屋同士は、つながりつつも全てが同時に見渡せるわけではありません。それぞれに流れている時間のスピードが異なっているのです。家が呼吸している、と言えますか。自由に移動できるということは、空間を考える上でも非常に触覚的で具体的な性質の一つだと思います。

一方で、行き止まりの空間が持つ確固たる魅力も否定できません。門によって閉ざされているという意味で、このアブ&フォント邸も行き止まりの建築なのです。通りからこの家へと向かっていくと、背の高い中庭の壁、そしてエントランスの門が見えてきます。そこには明確な境界線が作られています。そして、中へ入るとそこがまるで別空間のように感じます。敷地全体が家となっているのです。つまりは、今まさに始まったはずの建物へのアプローチもそこで終わってしまうのです。

歩みを止め、その囲われた空間を見渡してみます。メインスペースとなる空間の床は、地面から持ち上げられていて、強い存在感が感じられます。フィーレンディールトラスから吊り上げられたセラミックのスラブ天井は素晴らしいものですよね。その緩くカーブした天井と、持ち上げられた床との間の空間には、上下からの圧縮力が働いているように感じられます。まさに、ここで生活が展開されるのです。

使用されている素材に関しては、レンガが多いですよね。ガレージのドアのような可動式の木の素材も気になりますが、素材に関してはどうお考えですか。

木のパネルと重いチェーンによって、空気の流れを変えたり、日差しを遮ることもできるわけですが、中世的なギミックと表現ですよね。

実用性によるものですが、魔術的な空間の魅力を感じます。私には、その木のパネルに取り付けられたチェーンが、まるで鳩時計のように正確に動き出し、内部の空間を閉じたり、開いたりして、クライマックスを演出する建物の姿が想像できるのです。鉱物のように動かないはずの建築とは対照的なこのフィクショナルなリズムは、石の中の時計、のイメージとでも例えられるでしょうか。

パラグアイは、ヨーロッパの気候条件とは大きく異なりますよね。そうした南方のエキゾチズムは、北方の建築家にとってどのように受け止められるのでしょうか?

内部と外部の関係に関しては得るものが多いですね。ですが、北欧のような気候の中で建築を作る難しさにも感謝しているのです。寒冷地であるという外的な制約がありますから、建築家として探求したいことの全てを実現することは難しくなります。ですが、だからこそ作品が個性的なものになるのだと思います。アブ&フォント邸のメインスペースには確かに壁が存在していません。内部空間そのものがそこにはあるのでしょう。スロープのスクリーンや回遊導線、そして舞台のように高く上げられた床。演劇的なシチュエーション。そう、これこそが私たち北方の人間が学び、考えるべきことなのでしょう。建築を通して実現されたパフォーマンス性の高い生活の姿です。

この家では、その構造的な発明が家族の集まるリビング空間に現れています。主構造と空間との関係についてはどうお考えですか?

アブ&フォント邸においては、構造体の存在自体もそうですが、構造が空間を形づくるその方法自体が美しいですね。強烈で独創的なレンガの構造体が、実は家族の集う空間のために選ばれたものであると気づくでしょう。家は誰かと集まるための空間であり、何かを共有する場所であるべきだという意識が感じられます。

私がこの家に興味を持っているのはおそらく、そこにエートスを感じるからでしょう。それは、家族が集まり幸福を感じることによって作られるものです。もちろん家の構造的なアイデアは魅力的ですし、素材の使い方も斬新なものだと思います。ですが、私の感動はそうした大胆な試みが、押しつけがましく主張していないことにあるのだと思います。ただ必要だから、そこにあるといったように。結果的に、ソラーノさんの母親が安心して過ごし、家族が集る安心した世界をつくりだそうとする意思が感じられます。

私たちマンタイ・クラは、これまでに実現したプロジェクトは多くありません。ですが、私たちにとって構造というものは常に建物のアイデアと深く結びついているものです。ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラはレンガ使いの名人ですよね。それに比べて私たちはもっとシンプルな方法ではありますが、どちらの事務所にとっても、構造の存在は空間を考える上で極めて重要だと思います。そうでなければ面白くありません。

私たちの場合、構造の存在は不可欠です。構造は、物事の相互関係を理解させてくれるものです。世界のより大きな次元との関係を構築する存在、例えば、重力、空間、時間、あるいは、近づきたくても近づけない、見たくても見ることのできない、そうした無形の現象と関係を結ぶきっかけとなる存在なのです。

空間体験と構造的なアイデアとが結びついた建物には、実存的な感覚が宿るのだと思います。世界の他の地域と同じように、ノルウェーのほとんどの建築物は面白くありません。たいていの人は、写真映えする商品としての建築に興味を持ったとしても、それが環境に対していかに有意義な相互作用をもたらすかといったことには興味がないのです。

大昔の話になりますが、私が学生だったころは違いました。オスロの建築大学の教授の一人にスヴェレ・フェーンという人がいました。彼は、コンストラクションという概念に取り憑かれていました。そこで私たちは空間と素材を関係づけるには構造的なロジックが必要であることを教えられました。構造は建築の主人公として、空間の質と生活の質、その両方に必要とされるものなのです。

私はこのロジックにこそ、建築における永遠の可能性を信じていますし、実務的な側面からそう学生に伝えています。あらゆることが可能になり、あらゆる形が物理的に作り得る今日です。私たちは一体何を見て、何に囲まれているのか、そうしたことを考え理解していなければ、世界から阻害されていくように感じます。自身の感覚を通じて、空間や場所とつながることは、人間の根源的な欲求なのでしょう。

アブ&フォント邸では、構造は装飾的なものではなく、構造としての本来の目的を果たしています。母親の寝室の写真をご覧になりましたか?梁と外壁との間に鉄の補強が見えるでしょう。こうした仲間外れの要素も、空間に心地よさを作り出す要因なのかもしれませんよね。

ノルウェーのアカデミックな建築の世界においても、こうしたテクトニクスを重視した建築は減ってきているようですが、その原因はどこにあるのでしょうか?

BH: 例外もありますが、大量生産される建築に関しては、全くその通りだと思います。莫大な資金が流入したからでしょう。ノルウェーは石油を発掘したのですが、石油は富をもたらしますよね。それで不動産も発展したのでしょう。クライアントは自分自身のために建築を考えなくなり、むしろその出口戦略を考え始めます。要は、クライアントと建築家との対話が、永続的なものから短期的に回収できるものへと変化したのです。建物は市場の需要を満たす必要がありますから、建築は商品となり下がってしまい、その質について深く議論されることがなくなりました。リスク回避の考え方も、建設に大きな影響を与える要因です。過去数十年の間に、建築家の仕事を管理するシステムや役割は劇的に増加しましたし、プロジェクトやそのプロセスは、リスクを回避するために標準的であることを強いられるのです。

高い質を担保しながら、テクトニクス的にも面白い建築を作ろうとするならば、頑なに信念を貫き通す必要があります。いや、安全でかつ簡単な解決策もありますが。標準的な仕様に従いながら、うまくそれらを隠蔽し、表面がまだ綺麗なうちに腕の良いカメラマンに撮影してもらえば良いのです。

やや哲学的な問いになってしまいますが、建物の構造自体に自律性や可塑性が担保されていさえすれば、実はそれだけで十分なのではないでしょうか。つまり、そうした構造を持つ建物は、特定のプログラムに縛られることなく、将来的に別の用途の建物に変更することができるのではないでしょうか。どうでしょうか。そうした問いかけをクライアントにもされたりしますか?こうした建築家の野心は理解され得るものでしょうか?

ほとんどの建築は本当にそうですよね!アブ&フォント邸の地下には、屋根を支える奇妙な、しかし美しいレンガのトラスがありますよね。いくぶん曖昧な空間なのですが、そのトラスのおかげで空間が引き締まっているように感じます。その地下空間は、家族の誰かが使う予定で作られたものなのですが、私たちが訪れた時には、すでに竣工から10年が経っていて、ガビネット・デ・アルキテクトゥラの事務所として使われていました。

建築家として、あるいはビルダーとしてあなたはこの世界に何かをもたらすことになります。後世に残すものが意味のあるものとして、人々がそれを認識し、関わり合い、利用できる存在であることが重要です。ですから、構造やテクトニクスはとても重要なのです。それは、建物に価値を与えてくれるのです。

誰もがそう感じるわけではないですが、同意してくれる建築家はたくさんいますよ。それはつまり、建物に超越的な性質を与えるということですが、クライアントにもそうした話をしなくてはいけないのですよね。だから私たちは実現した建築が少ないのでしょうね(笑)

構造が剥き出しになっているような建築は、極端にわかりやすく感じてしまうこともありますし、逆に複雑に感じることもあります。アブ&フォント邸の構造は、それぞれを個別に見ると、すぐには理解できないような空間が作られていますよね。そうした「すぐには理解できない」ことについては、どうお考えですか?

全てを理解することは目的ではないですし、むしろそうすべきではないと私は思っています。重要なことは、一部の要素が他の要素よりも強い意味を持っているということです。私が建築のコンセプトとして構造に興味を持っている理由の一つは、ヒエラルキーが設定できるからです。ゲームのルールと捉えても良いでしょう。

例えば、私たちの設計したフォアウィックのフェリーポート(2015年)は、小さなサービス用の建物なのですが、その主構造と形式的な解決策として、逆さまにしたスティールの円筒形ヴォールトを採用しました。私はそれが正しいと思っていましたし、そうあるべきだと感じていました。それは同時に、技術的な課題や空間的な制約も生み出してしまいましたが、逆さまにしたヴォールトというロジックの中から、二次的な構造やディテールを考えていくことが可能となり、作品にも方向性が生まれてきたわけです。ハンブルク・ハウス(2021)においても同様に、住宅を支える集成材のアーチが設計のルールを決定しています。

つまり、私たちが興味を持っているのは、構造的な思考と素材の論理とのヒエラルキーを注視していくことで、建築がどのような方向性を獲得し得るのか、ということなのです。今日ではどんな形のものでも建てることができるでしょう。しかし、何を基準に決めていけばいいのでしょうか?いや、これが重要なのだと一度決めてしまえば、その選択によってプロジェクトは進んでいくはずです。私たちの場合、この最初の決定が物を作るプロセスに関係してきます。それと重要なことは、論理の破綻を許容しながら、しかしなお追及を続けることです。ヒエラルキーに反抗的な逸脱は、美しい瞬間をもたらすこともあります。私はロードマップが合理的であることに満足感を得ることが多いタイプですが、その過程で非合理的な衝動で、判断してしまうこともあります。いや、それこそが私たちが建築において探求していることですから。

24年6月3日

Beate Hølmebakk: Paraguayans sometimes describe their country as an island surrounded by land. And as though this land is a turbulent sea, it is not so easy to reach the place.

I first saw the Abu & Font house in the O’Neil Ford Duograph 5, edited by Barbara Hoidn and published in 2013 by the University of Texas at Austin. I found the house, which was designed for his mother, remarkably interesting, and decided to reach out personally to Solano Benítez. In the spring of 2016, I travelled to Paraguay with a group of students to visit the house, we also looked at other projects by Gabinete de Arquitecture and by Javier Corvalan. I believe it surprised Solano that we came, but he was very welcoming and generous with his time. Later the same year I invited him to Oslo to present the work of the studio to the whole school.

THE HOUSE IS SPECIAL IN THAT THERE ARE MULTIPLE WAYS TO REACH THE DIFFERENT SPACES. WHAT’S INTERESTING ABOUT BEING ABLE TO MOVE THROUGH A BUILDING IN VARIOUS WAYS?

This is true. I think a house needs to have this quality; to be open and not constrain people’s lives. This house breathes; the ramp is slower than the stairs, the screen in front of it masks your movement; rooms are connected but at different speeds and not all on view. Freedom of movement is a very tangible quality within space.

On the other hand, the appeal, or definite quality, of a dead-end is for me undeniable, and being a gated building; the Abu & Font house also has this quality. Approaching the house from the street, you meet the tall garden wall and the entrance gate– offering a clear threshold. Upon entering, you find yourself in a world of its own, the house occupies almost the entire site, defines its own limit and ends the path you began on.

Ceasing to move, taking in the enclosure, the raised floor of the main space has a strong presence. A large space seems almost compressed between this floor and the fabulous, slightly vaulted, ceramic slab, suspended from the Vierendeel beams. Life in this house unfolds here.

IN TERMS OF MATERIAL, BRICK CLEARLY DOMINATES, HOWEVER THERE ARE ALSO MOVABLE WOODEN ELEMENTS; LIKE THE GARAGE-LIKE DOORS. WHAT IS YOUR SENSE OF THEM?

With their timber structure and heavy chains, these kinetic elements are medieval in expression and operation, adjusting airflow, shade, and protection.

This is a pragmatic, yet magical space, and to me it felt as though the chains of the panels could be made to work with the precision of a Cuckoo-Clock, building towards a climax of the opening or closing of the space. I remember imagining this fictional rhythm in contrast to the fixed mineral construction, like a clock within a stone.

GIVEN EUROPEAN CLIMATIC CONDITIONS ARE VASTLY DIFFERENT, WHAT LESSONS CAN THESE EXOTIC SOUTHERN REFERENCES OFFER NORTHERN ARCHITECTS?

Southern houses offer lessons in the relationship between inside and outside. However, I’ve always appreciated the challenge of building in Northern European climate. Given the external constraints of a cold climate, it’s hard to achieve some of the qualities you’re searching for as an architect, but we tend to think that this difficulty is what gives character to our work. In the main space of the Abu & Font house, the walls are missing, yes, but the central focus is on the interior space itself: the screen, the circulation, the stage-like raised floor. It is a theatrical situation, and maybe that’s something we can learn from and think more about up here in the north: a more performative life facilitated through architecture.

THE STRUCTURAL INVENTION OF THIS HOUSE IS REVEALED IN THE SPACE WHERE PEOPLE GATHER. HOW IMPORTANT IS THE RELATION BETWEEN COLLECTIVE SPACE AND PRIMARY STRUCTURE FOR YOUR OWN PRACTICE?

In the Abu & Font house the presence of structure and how it defines space is beautiful. You really feel that the impressive and original brick structure is made for gathering the family. There is an understanding that a house is a collective space, a place where you share something with others.

This is probably where the center of my interest in this house lies: it’s ethos being defined by the collective nature of families and their well-being. It is without doubt a fascinating project structurally, and it is quite innovative in its use of material, but what I find touching is that these bold gestures are not imposing or making too much of themselves; they simply exist and seem necessary. Consequently, what you feel when you are there is the strong ambition of creating a protected world where Solano’s mother could feel safe, and where the family could gather with her.

Manthey Kula has not realized many projects, but for us, structure has always been deeply connected to the very idea of building. Gabinete de Arquitectura are virtuosos in their use of brick while our work is much simpler, but I believe that the presence of structure is pivotal in terms of space for both practices – otherwise, it’s just not that interesting.

In our case the presence of structure is essential because it helps us understand how things work together. It sets up a relationship with the larger dimensions of the world: gravity, space, time, and other immaterial phenomenon that you want to feel connected to - to make sense of - but often don’t.

In this way buildings where the spatial experience is connected to a structural idea therefore have an almost existential dimension. In Norway, like many places, what’s being built is mostly uninteresting. Most of the people involved in building seem to be more interested in creating photogenic commodities than in contributing to meaningful environments where buildings make sense and interrelate.

Years ago, when I was a student, it was different. Sverre Fehn was one of the professors at the school of architecture in Oslo. He was occupied with the idea of construction. We were taught that there had to be a structural logic ordering the relationship between space and material. Structure was the protagonist, essential and meaningful to both the quality of space and to the sense of life.

I believe this logic is an eternal potential in architecture and talk about this side of practice with my students. Today, when anything is possible, and every form can be given physical presence, if you don’t make sense of what you’re looking at or of that which surrounds you, you become alienated. To feel connected to space and place through a notion of sense is a fundamental visceral human need.

In the Abu & Font house, the structural elements are not decorative; they serve primary purposes. You’ve seen the pictures of the mother’s bedroom, with the steel bracing between the beam and the outer wall? I imagine that the presence of this solitary element must evoke a feeling of comfort.

WHAT CAUSED THE LOSS OF TECTONIC ARCHITECTURE IN NORWAY, EVEN AT THE LEVEL OF ACADEMIA?

There are exceptions, but for the mass construction it is true. I guess what happened was an enormous influx of money. Norway found oil, with oil came wealth and with wealth came the flourishing of real estate development. Clients stopped building for themselves and started building with exit agendas. To say it simple: The focus of the dialogue between clients and architects changed from lasting qualities to quick returns. Buildings should meet mainstream market demands. Architecture became a commodity, and the deep discussion of what architectural quality should or could be disappeared. Risk aversion became a main influence of what was being built. The number of systems and roles that control architects’ work increased dramatically during the last decades. Projects and processes are now rigged to avoid risks and follow standards.

High quality architecture with well-made and interesting tectonic features requires conviction and stubbornness, the safe and easy solution is to do the standard thing, cover it up and get a good photographer to shoot while surfaces are still fresh.

PHILOSOPHICALLY SPEAKING, IF A STRUCTURE HAS ITS OWN AUTONOMOUS, PLASTIC QUALITY, NOTHING ELSE REALLY MATTERS - A BUILDING WITH A COHERENT STRUCTURE IS NOT TIED TO A SPECIFIC PROGRAM AND CAN THUS BECOME SOMETHING ELSE IN THE FUTURE. WHAT DO YOU THINK - HOW WOULD YOU COMMUNICATE THIS INTENTION TO YOUR CLIENTS? IS THIS AMBITION COMPREHENDIBLE?

It is most certainly so! Think about the strange and beautiful brick trusses that support the roof in the basement of the Abu & Font. They give the somewhat indeterminable space a distinct character. The basement was built to accommodate some of the family members. When we visited, ten years after the house’s completion it was the office of Gabinete de Arquitectura.

As an architect, or a builder, you bring something into the world. It is of importance that what you leave behind makes sense and have a presence that those who come after us can perceive, relate to and make use of. This is why structure and tectonics are so important: they give value to the building.

Not everyone feels this way, but I know many architects who do. It’s about giving the buildings transcendental qualities. You must be able to talk to clients about this. Maybe that is why we have built so little (laughs).

AT FIRST GLANCE, EXPOSED STRUCTURE CAN BE EXTREMELY CLEAR OR EVEN RATHER COMPLEX. THE STRUCTURE IN THE ABU & FONT HOUSE CREATES MANY SPACES THAT, SEEN SEPARATELY, ARE NOT IMMEDIATELY UNDERSTANDABLE. WHAT DO YOU THINK ‘NOT UNDERSTANDING EVERYTHING IMMEDIATELY’ BRINGS TO A BUILDING?

Understanding everything isn’t necessarily the goal, quite contrary I believe. What’s important is understanding that some parts are more important than others. One reason I’m interested in structure being part of the main concept of a building is because it sets a hierarchy: You could say it defines the rules of the game.

For example, we designed the Forvik ferry port (2015) with a single inverted steel barrel vault as the main structural and formal solution for a small service building. It felt right, like it had to be that way, but simultaneously it created a series of technical challenges and spatial constraints. Working out the secondary structure and the details within the logic of the upside-down vault, gave the work a sense of direction. The same thing was the case with the House at Hamburgö (2021); the glulam arches that carry the house set the rules for the design.

So, what interests us is how architecture gains orientation through observing hierarchies of structural thought and material logic. Today, you can build almost any form, but what guides you in making decisions? Once you’ve said that one thing is important, the development of the projects can be guided by this choice. In our case this first decision is often connected to how things can be made. What is important to add is that one must allow, or even pursue logical breaks. Insubordinate deviations from the hierarchy may lead to moments of beauty. I often find satisfaction when the roadmap is rational, but when irrational impulses are recognized and implemented along the way. This is what we search for in architecture.

03.06.24

贝亚特·赫尔梅巴克: 巴拉圭人有时将自己的国家形容为一个被陆地包围的岛屿。而这片土地仿佛是波涛汹涌的大海,抵达此地并非易事。

我第一次见到阿布与丰特住宅(Abu & Font House)是在《奥尼尔·福特双联集第五卷》(O'Neil Ford Duograph 5)中。该书由芭芭拉·霍伊登(Barbara Hoidn)编辑,2013年由得克萨斯大学奥斯汀分校出版。这栋索拉诺·贝尼特斯(Solano Benítez)为母亲设计的住宅令我格外着迷,于是我决定亲自联系他。2016年春天,我带着一群学生前往巴拉圭参观这栋房子,同时还考察了建筑工作室(Gabinete de Arquitectura)以及哈维尔·科尔瓦兰(Javier Corvalan)的其他作品。我想我们的到来让索拉诺有些意外,但他非常热情,慷慨地为我们腾出时间。同年晚些时候,我邀请他到奥斯陆向全校展示工作室的作品。

这栋住宅的特殊之处在于,进入不同空间的方式有多种。这种在建筑中“以不同路径穿梭”的体验,其趣味性来自哪里?

确实如此。我认为一栋住宅需要具备这种特质——开放而不束缚人的生活。这栋房子是“会呼吸”的:坡道比楼梯更缓慢,其前方的屏风遮蔽了你的移动轨迹;房间彼此连通,但节奏各异,并非一览无余。行动的自由是空间中一种非常具体的品质。

另一方面,对我来说,“死胡同”的吸引力——或者说某种明确的空间特质——是无法否认的,而作为一栋有门禁的建筑,阿布与丰特住宅也具备这种气质。从街道靠近它时,你会遇见高大的花园围墙和入口门扉——形成一道清晰的界限。一旦进入,便发现自己置身于一个独立的世界:住宅几乎占据了整个场地,划定自身的边缘,终结了你来时的路径。

停下脚步环顾四周,主空间抬高的地面存在感尤为强烈。这片广阔的区域仿佛被压缩在这层地面与悬浮于空腹梁(Vierendeel beams)之下的微拱形陶板之间。这座住宅的生活场景在此徐徐展开。

就材料而言,砖无疑是主导元素,但也有可移动的木构件——比如车库门。您如何看待它们?

这些带有木结构和沉重链条的动态构件,无论形态还是操作方式都透着一股中世纪气息,用于调节气流、遮阳与防护。

这是一个实用却充满魔力的空间。对我而言,墙板的链条仿佛可以像布谷鸟钟般精密运作,将空间的开启或闭合推向某种仪式性的高潮。我仍记得自己曾想象这种虚构的节奏——它与固定的矿物结构形成对比,如同石头内部嵌着一座时钟。

考虑到欧洲气候条件差异巨大,这些来自南半球的异域经验能为北方建筑师提供什么启示?

南方的住宅教会我们思考内外关系。不过,我一直欣赏北欧气候下的建造挑战。寒冷气候的外部限制让我们难以实现某些建筑师追求的特质,但正因这种困难,我们的作品反而获得了独特个性。在阿布与丰特住宅的主空间中,墙体虽被消解,但核心聚焦于内部空间本身:屏风、动线与舞台般的抬升地面。这是一种戏剧化的场景营造——或许我们北方建筑师可以从中学习,更多地思考如何通过建筑促成一种更具“表演性”的生活。

这座住宅的结构创新体现在人们聚集的空间中。对您而言,公共空间与主体结构的关联有多重要?

阿布与丰特住宅中结构的在场感及其对空间的界定方式非常美妙。你能真切感受到,这座令人惊叹的原始砖构筑物是为家族团聚而设计的。它传递了一种理念:住宅是集体空间,是与他人共享的场所。

这或许正是我对这座住宅最感兴趣的核心:其精神由家族的集体性与福祉所定义。从结构上看,它无疑是迷人的项目,材料运用也颇具创新性。但最触动我的是,这些大胆的手法并未显得强势或过度张扬;它们只是存在,且仿佛理应存在。因此,当你置身其中时,感受到的是一种强烈的抱负——创造一个受庇护的世界,让索拉诺的母亲感到安全,让家族得以围绕她团聚。

曼泰·库拉(Manthey Kula)事务所完成的作品虽不多,但对我们而言,结构始终与建造的本质紧密相连。Gabinete de Arquitectura是运用砖材的大师,而我们的作品更为朴素。但我相信,结构的在场感对两种实践的空间塑造都至关重要——否则建筑将失去趣味。

在我们的实践中,结构的显性至关重要,因为它帮助我们理解事物如何协同运作。它建立起与更宏大维度世界的联系:重力、空间、时间,以及那些你想要感知却难以捉摸的无形现象。

因此,当空间体验与结构理念相连时,建筑便获得了近乎存在主义的维度。在挪威,正如许多地方一样,当下的建造大多乏善可陈。多数从业者似乎更热衷于打造“上镜商品”,而非创造建筑之间相互关联、富有意义的场所。

多年前我求学时,情况截然不同。斯维勒·费恩(Sverre Fehn)曾是奥斯陆建筑学院的教授之一。他执着于建造的本质。我们被教导必须用结构逻辑统摄空间与材料的关系。结构是主角,对空间品质与生命感知皆不可或缺。

我相信这种逻辑是建筑永恒的潜能,并常与学生探讨实践的这层维度。如今,当一切形式皆可实现,若无法让人理解所见之物与所处环境,人便会感到疏离。通过“意义感”与空间场所建立联系,是人类根深蒂固的本能需求。

在阿布与丰特住宅中,结构元素绝非装饰,它们承担着核心功能。你见过那间母亲卧室的照片吗?梁与外墙之间的钢制支撑仿佛孤独的卫士,其存在本身便传递着令人安心的力量。

为何挪威的建构建筑传统日渐式微,甚至在学术界亦然?

虽有个例,但批量建造确实如此。我想根源在于资本洪流。挪威发现石油后,财富催生了房地产繁荣。业主不再为自己建造,而是带着退出策略投资房产。简言之,业主与建筑师对话的重心从永恒品质转向快速回报。建筑需迎合主流市场需求,沦为商品,关于建筑本质的深度讨论随之消失。风险规避成为主导,过去几十年间,管控建筑师工作的体系与角色激增,项目流程被设计成规避风险、遵循标准的流水线。

具备精妙建构特征的高品质建筑需要信念与固执,而安全省力的做法是套用标准方案、掩盖本质,再找优秀摄影师在表面光鲜时拍摄。

从哲学角度,若结构具备自主的可塑性,其他皆可让步——结构连贯的建筑不必绑定特定功能,未来可化身他物。您如何向客户传达这种理念?这类抱负能被理解吗?

当然可以!想想阿布与丰特地窖中那些奇异而美丽的砖砌桁架,它们赋予了这个模糊空间独特的性格。地窖原为家族成员设计,十年后我们探访时,这里已成为Gabinete de Arquitectura的办公室。

作为建筑师或建造者,你为世界增添事物。重要的是,你留下的作品需具备可被后人感知、关联并使用的在场感。这正是结构与建构如此重要的原因:它们赋予建筑价值。

并非所有人都认同这点,但我知道许多建筑师心有共鸣。这是关于赋予建筑超越性的品质。你必须能与客户谈论这些——也许这正是我们建成作品寥寥无几的原因(笑)。

外露结构初看可能极其清晰,也可能相当复杂。阿布与丰特住宅的结构创造了诸多乍看费解的空间。您认为“无法即刻理解一切”为建筑带来了什么?

理解一切绝非目标,恰恰相反。重要的是认识到某些部分比其他部分更关键。我对结构成为建筑核心理念感兴趣的原因之一,是它确立了层级——可以说,它定义了游戏的规则。

例如,我们设计的福尔维克轮渡码头(2015)以一樘倒置钢制筒拱作为服务建筑的主结构与形态方案。这方案直觉上正确,却也带来技术挑战与空间限制。在倒置拱逻辑下推敲次级结构与细部,为作品赋予了方向感。汉堡岛住宅(2021)亦如此:胶合木拱架设定了设计规则。

我们关注的是建筑如何通过结构思维层级与材料逻辑获得方向性。如今你几乎可以建造任何形态,但决策的依据是什么?一旦确定某要素至关重要,项目发展便可由此引导。对我们而言,这初始决定常与“如何实现”相关。需补充的是,必须允许甚至追求逻辑断裂——对层级的叛逆偏离可能催生美的瞬间。当路线理性而过程中接纳非理性冲动时,我常感到满足。这正是我们在建筑中追寻的。

24年6月3日

Beate Hølmebakk

is professor at the Institute of Architecture where she is responsible for studio TAP – The Architectural Project that runs two master courses in building design: Building in landscape and Building in life. The teaching focuses on conceptual clarity, structural logic, and architectural form. Together with Per Tamsen she is founder of Manthey Kula, an internationally recognized architectural office working between architecture, landscape architecture and art. The office is nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award i 2009, 2011, 2019 og 2022 and represented in several international architecture collections, biennales and exhibitions. Beate Hølmebakk has her architectural education from AHO and The Cooper Union in New York. She has been professor at the Chalmers technical university and guest professor at Universidad de Navarra og Cornell University.

Beate Hølmebakk

is professor at the Institute of Architecture where she is responsible for studio TAP – The Architectural Project that runs two master courses in building design: Building in landscape and Building in life. The teaching focuses on conceptual clarity, structural logic, and architectural form. Together with Per Tamsen she is founder of Manthey Kula, an internationally recognized architectural office working between architecture, landscape architecture and art. The office is nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award i 2009, 2011, 2019 og 2022 and represented in several international architecture collections, biennales and exhibitions. Beate Hølmebakk has her architectural education from AHO and The Cooper Union in New York. She has been professor at the Chalmers technical university and guest professor at Universidad de Navarra og Cornell University.

Beate Hølmebakk

is professor at the Institute of Architecture where she is responsible for studio TAP – The Architectural Project that runs two master courses in building design: Building in landscape and Building in life. The teaching focuses on conceptual clarity, structural logic, and architectural form. Together with Per Tamsen she is founder of Manthey Kula, an internationally recognized architectural office working between architecture, landscape architecture and art. The office is nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award i 2009, 2011, 2019 og 2022 and represented in several international architecture collections, biennales and exhibitions. Beate Hølmebakk has her architectural education from AHO and The Cooper Union in New York. She has been professor at the Chalmers technical university and guest professor at Universidad de Navarra og Cornell University.