ルイス・カレジャス:2014年のことです。シャーロットと私は一緒に仕事を始めようとしていたころ、ロサンゼルスのキュレーター、ミミ・ツァイガーからの誘いで、V.D.L.ハウスに一週間滞在して作品を展示することになったのです。私たちが初めて一緒に取り組んだプロジェクトでした。この家で過ごした時間は私たちの事務所の新しい道筋への重要なステップとなりました。

V.D.L.ハウスにノイトラはクライアントを招待し、空間や素材の実験を行っていたのです。贅沢さへの考え方が変わりつつある時代の中で、慎ましさなど、どういった質が意味をもちえるのかを探求していたのです。生活空間であると同時に、作業場でもありオフィスでもありました。この状態やライフスタイルはとても刺激的に思えました。

これは単なる住宅ではなく、未来の住宅のプロトタイプなんですよね。

V.D.L.ハウスは、次世代の住宅だと言えるでしょう。ノイトラはリサーチハウスと呼んでいました。以前にもいくつかこういった実験的アプローチの住宅を見ていましたが、典型的な実験住宅は日々進化するもので、ブリコラージュ的性格があり、あまり興味を持てませんでした。

私にとっては、プロジェクトに明確な意図があることが重要なのです。とはいえ、ある程度の「ワーク・イン・プログレス」的雰囲気や試験性、それに未完成であることの良さもわかります。そういった探究心が自由で開放的な感覚を作り出してくれるものです。いい意味で力みがなく見えるのだと思います。

最新のプロジェクトでは、同じようなことを試みました。次のプロジェクトへのテストとして、断片やディテールを試してみたのです。

詳しい例をあげると、美しい森の中の傾斜をもった空き地に、二つのボリュームの住宅を完成させたのですが、同じ素材、同じ型枠、同じディテールをほぼ同じ表面積の二つの住宅に用いたのです。私たちの興味は、地表面に対する平面の幾何学、それと構造の配置の違いによって、どう空間が感じられるのか、ということでした。細長いものと正方形のもの、半分沈んでいるものと高さのあるもの。前者は擁壁のようで雨季には湿度を高く感じ、後者は風通しがよく外向的に感じられる。これら二つの実験が行われたことで、80ヘクタールある敷地に、今後どのような家を建てていくかをクライアントと話し合うことできました。

V.D.L.ハウスは私たちの建築の作り方に近いものです。少なくとも私たちの目指すものに近いと感じています。まさに将来の依頼を受けるための住宅。今思うと、そこで過ごした時間が先ほど説明したプロジェクトに影響を与えたのだと思います。サラ・ロレンゼンさんと夫のデイヴィッドさんが、中庭の向かいにある小さなノイトラのゲストハウスに住んでいたことを思い出します。私たちは毎日庭でおしゃべりをしていました。コーヒーに誘ってくれたりもしました。見知らぬ者同士や友達同士、家族同士が庭を隔てた近くに住みながら、日常のひょっとした偶然から、誘い合ったりできるこのアイデアは本当にいいですよね。結局、私たちはエル・レティロの住宅でも同じことをしていたのです。つまり、広大な庭と二つの独立した構造がこうした出会いを可能にしているのです。

ノイトラは、北の国オーストリアからやってきてカルフォルニアに移住しました。あなたの仕事は、気候や地理的条件の全く異なる北と南の世界を横断していますが、この二面性についてはどのようにお考えですか?

私はコロンビアに生まれてそこで建築をはじめました。トロピカルモダニズムのディープなところでね!シャーロットはスウェーデン出身です。私たちはあなたのおっしゃるように、二つの異なる世界を結びつけながら活動をしているのです。現在はオスロに拠点を置いていますが、ここはある意味、文化的な周縁なのです。コロンビアとは少し違う意味でね。

私たちの場合は、北から南のことを考える、つまりオスロに住みながら熱帯のアンデス山脈の建物を考えるということをやっているのです。家に近い方が最高の仕事ができる、という神話が嫌いなのです。作家が自分の言語で書くことについては、何度も言われていることです。ただ、場所やロケーション、気候、それに政治についてはまた別の話だと思います。遠距離での対話は、パワフルなもので、現場で書き物をしたりデザインしたりするよりもコンテクストに沿った何かを引き起こせると考えているのです。

実際、私自身の状況を理解するためにも、芸術家や建築家が故郷から離れ、異なる気候や文化、植生に直面したときにこそ最高の仕事を成し遂げてきた事実に長い間、関心を持っていました。ジェームス・ジョイスがチューリッヒからアイルランドを想起していたことを思い浮かべるのです。それにヨーン・ウッツォンとキャン・リス。北欧の建築家が行った気候的障壁のない生活の可能性への探求。ヨーロッパから移住してカリフォルニアにやってきたノイトラも同じですね。彼らは気候的に解放された建築家たちでした。同じような素晴らしいストーリーはまだまだたくさんあります。私たちの仕事においては、特定の場所との深い関係性を築くことがとても大事なことなのです。その場所から遠く離れながらも、その距離によって、始まりの地で生まれた一つのアイデアをいかに強化できるかを真剣に考えていくのです。

ノルウェーは冬になると当然のことながら寒いのです。オスロにいながらコロンビアのプロジェクトを進めていると、南米にいた時には当たり前だと思っていたことが懐かしく感じられることがよくあります。この懐かしさが意思決定のプロセスやイマジネーションに影響を与えます。結果としてのノスタルジーが、現場の近くにいるだけでは思い付かないような解決策を導き出すのです。

例えば以前は、21℃という温度は室内の温度としては寒いものだと思っていましたし、アンデス山脈の高地にある住宅には、しっかりとした断熱性能が必要だと考えていました。ですがノルウェーに住んで以来、そういった場所でも窓がピッタリと完璧に密閉されていなくても大丈夫だろうと思えたのです。夜は18℃でも大丈夫なのだとわかったのです。セーターを着ればそれで解決するような問題ですから。熱帯の高地で働く建築家にとっては、18℃だと寒すぎるだろうと考えてしまい許容しにくいのでしょう。最近、私たちが完成させた住宅は、もっと開放的なものですし、窓のプロファイルも完全にしっかりと密閉されたものではありません。

南の地域から北の地域が学べることはどんなことでしょうか?

温暖な国にもそれぞれ様々な制約と可能性がありますね。ブラジルの例でいえば、優れた建築は宙に浮いているものが多く、少ない支柱で地面から持ち上げられています。地上階をいかに開放するか、たった二本の柱だけで、それ以上並べずに建てるにはどうすれば良いか、といったことを教えてくれるのです。コロンビアではそうできません。地震がありますから。地震が起きると、重力よりも横方向の力の方がはるかに強く働くのです。そのため、建築は垂直方向よりも横方向の力、ベクトルに対処することが重要です。ですから、大きなキャンティレバーはありませんし、重力に逆らう詩的な表現にも、あまり興味がありません。コロンビア建築は基本的にテルリック(大地から生じた)なのです。アンデス山脈の複雑な地形にも対応しなくてはいけません。フラットな場所など、ほとんどないのです。図面の中にコンターラインを書き込んでいき、その繊細なラインを操作することから住宅をデザインしていくことの愛おしさを学んでいくのです。建築行為の第一に大地の形状を再定義し、そして次には擁壁を作ることが多いでしょうか。

一般的に南の国々にもそれぞれの特徴があります。それらに反応することは、山岳地帯や森林が密集した同じような風景をもつ北の地域にとっても大きなインスピレーションとなり得るでしょう。

熱帯的状況から生まれる彫刻的な特質は、北方の建築へも影響を与えるものだと思います。こういった彫刻的な特質には予算がかからないのです。ですから、構造体は外部と内部の表現を定義しながらも控えめな存在であり、抑制されたエレガンスを保っているのです。

V.D.L.ハウスで準備されていた展覧会はどういったものだったのでしょうか。

私たちは、V.D.L.ハウスとシルバーレイクの貯水池との関係性に魅了されていたのです。貯水池はもともと小さな湖ほどのサイズの大きな水盤であり、コンクリートでできた小さなインフラの一部なのです。今では周囲の木々も育ち、実に小綺麗な湖のように見えるのです。近隣には住宅がたくさん作られてきていて、みんな貯水池の方を向いているのです。ところがノイトラが家を建てた時には、全然違った環境でした。

この家は、人工的な風景との関係を確立した1930年代半ばにおける最初の住宅なのです。ノイトラは、コンクリートの貯水池を、視線を向ける価値のある一つの風景として捉えていました。 その可能性を認識していたのです。彼は屋根の上に反射する水庭をデザインしたのです。ペントハウスの中で腰を低く下ろすと、貯水池の水平面にその水庭が溶け込んでいくのです。大きなガラス面は四方を見渡すことができ、日常の生活空間の中に周囲の存在が巻き込まれていくようにデザインされています。眺望、鏡面、陰り、反射などを操作するための多くの工夫が施されています。いくぶん小さな住宅が、領域全体における構成へと参加できるように促す試みであるのです。将来この地域に表出してくるであろう領域的全体性の中に、他の住宅が建つことを彼が夢見ていたのは当然のことだと思うのです。

私たちが訪れた時は、ロサンゼルスは深刻な干ばつの影響で貯水池はほとんど乾いていました。

周りの全ての住宅が、巨大なコンクリートの凹みを見つめている様は、ひどく異様な光景でした。それにV.D.L.ハウスは改修直後なこともあって、水庭が機能していなかったのです。日陰のない大きな窓からの景色や、特に日差しは不快に感じるほどに強烈なものでした。私たちは滞在中に、この住宅のデザイン意図の中核を深く理解するために、足りないものや不完全なものを追加し仕上げていく必要を感じたのです。

そこで、屋上のパビリオンに新しいシルクのカーテンを作り展覧会を開くことにしたのです。私たちがこれまでに手がけた様々な水辺のプロジェクトが連続的な流れをつくり、ひとつのドローイングとして、シルクのカーテンのデザインを形成するのです。屋上の水庭に水を満たすこともできました。

私たちのインスタレーションは、人工的な水辺の風景や、霞がかかった遠くの景色、明るさや心地よい影、水の近さについて語っているのです。それはV.D.L.ハウスの特質を伝えると同時に、ノイトラに近い魅力をもった私たちのプロジェクトを紹介するものでした。

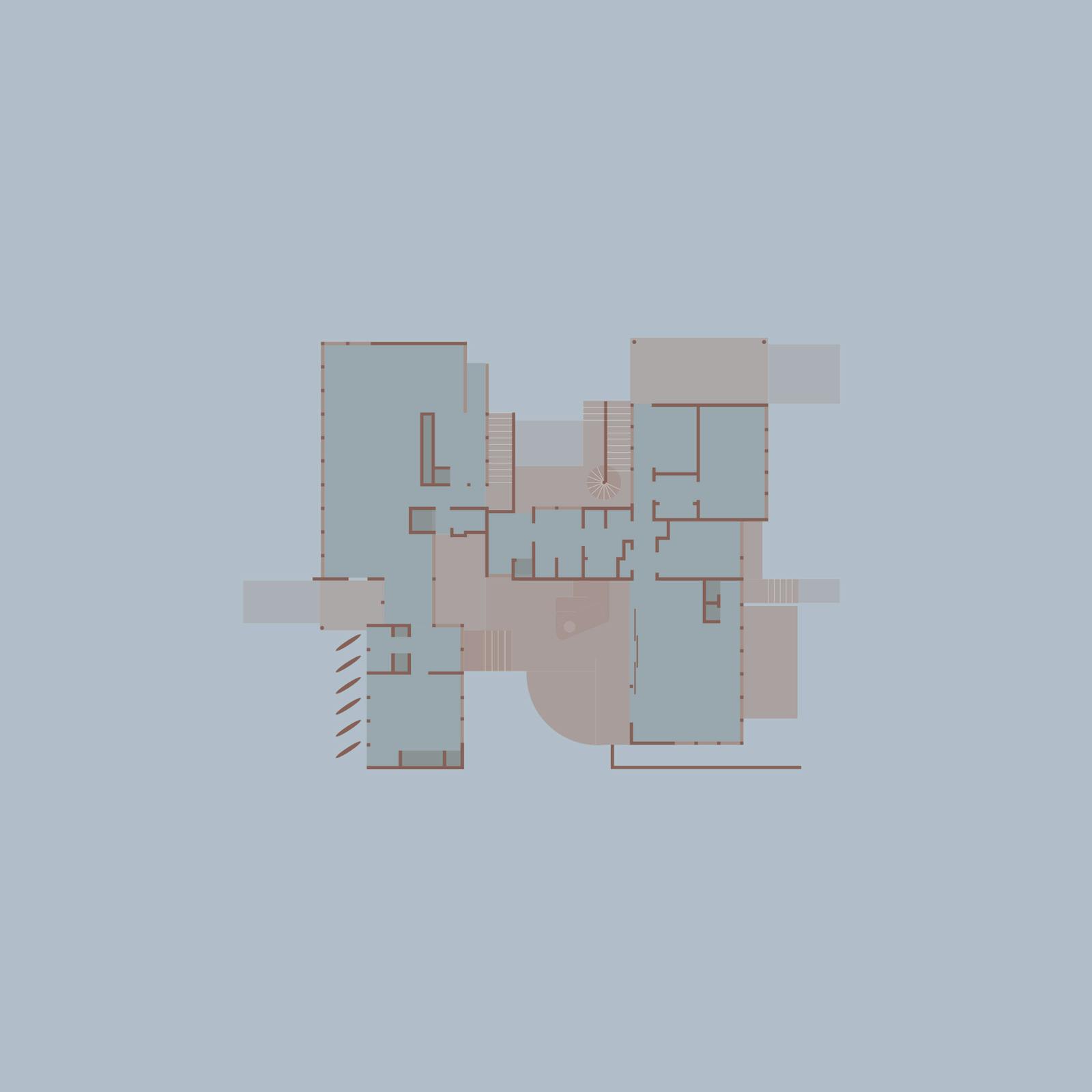

この家は木のように床のレベル差が全て異なっていますよね。視点が常に変化しているということですが、これは有機的なデザインだと呼べるものでしょうか?

有機的だとは言いませんが、考え抜かれた合理的で緻密なプランだと思います。作るプロセスや時間をかけて成長していくプロセスを恥ずかしげもなく、さらけ出しているという意味においては有機的だと思いますが。

ノイトラは風景と家の連続性を演出するために、どのような工夫をしたのでしょうか?

まず、ノイトラがランドスケープとタウンプランニングの素養をバックグラウンドに持っていたことへの指摘は重要だと思います。彼はヨーロッパのオーストリアからやってきて、スイスを経由し亜熱帯のカルフォルニアにやってきました。

そこでようやく美しい住宅で名を知られる建築家となったわけですが、実は彼はもっと大きなスケールでの仕事をしていたのです。多くの建築家は小さな仕事から始めて、歳を重ねるに連れて手がけるプロジェクトも大きくなっていくものですが、彼は逆のケースで、始めはタウンプランナーとして働いていたのです。それに植物のことが好きでよく知っていましたし、シンドラーの家の庭の設計も手伝っていたりしました。こういったバックグラウンドがどういうわけか、比較的小さな住宅建築の中にも表れてきているのです。つまり、より大きなコンテクストについても語れるプロジェクトのキャパシティがあるのです。この考えは、彼の著書である「Survival Through Design」 (1954)にも書かれています。

どんな小さなディテールからも、ノイトラがこの小さな建物を大きな領域の中に関係づけようとしていたことがわかります。この計画においての重要な構成は屋上の水庭ですよね。腰を据えるとその水庭が貯水池と視覚的に一体化し、反射面として風景の断片を反射し、壁や床に投影される。こういった判断の全ては、家の中だけに住むというのではなく領域全体の大きな風景に住むような感覚を生み出すためになされたことなのです。

住宅のプロジェクトをランドスケープのプロジェクトへと変えるためにどういった策略をとられていますか?

それは私たちの願望であることが多いですね。私たちの楽しみでもある実務的な部分についてお話ししますね。

建築とランドスケープは異なるものですし、分けて考えるべきだと思います。一方で、建築へのチャンスを、依頼もされていない庭園のデザインへと拡大していくといったこのゲームはとても楽しいものです。一般的に建築家は計画段階で、乾式か湿式かを区分していきますよね。後者はコンクリートの世界のことで、散らかった粉末を水と混ぜ合わせて構造物に流し込んでいきます。前者はソリッドな世界のことで、精密にカットされた素材や細い木材、ネジや仕上げなどのことです。

私は、主に身振りや表現としての湿式に興味があるのです。構造体が空間を定義するのです。

乾式にはそれほど興味がありません。乾式を把握して洗練させていくには、綿密な計画が必要です。それに様々な種類の的確な職人芸や、高価な材料なども必要です。それに最も重要なことは、それに多くの時間がとられてしまうことです。

私は、キャリアのかなり早い段階から、乾式の仕事を省略することでランドスケープなどのもっと興味深いトピックを議論のテーブルに持ち込む時間を確保できるだろうと考えるようになりました。「乾式」へのエネルギーと予算をランドスケープや庭のディテールに還元できるような建物を描くことができれば、単純にデザインの幅が広げられると思うのです。つまり、建築とランドスケープは同じではありませんが、良いランドスケープは過度に洗練された仕上げよりも、いい意味で建築を補完することができるのです。インテリアデザインに対する先入観を捨てて、庭に取り組むようクライアントを説得してみてはどうでしょうか?私たちは率直にクライアントに伝えていますよ。平凡な内装材に使うような資源があれば、とても立派な庭ができますよ、と。

私たちにとって庭は、普段目にできないような空想的な何かを作り出す可能性を与えてくれるものなのです。庭は超現実的なもので、合理的な構造物を補完するには最高の存在なのです。家の中に庭を入れるという話ではないですよ。自然と人工という話でもありません。それは生きたファンタジーなのです。庭は芸術なのです。

庭を造るにあたって、インスピレーションを受けるものは何ですか?

私は公共のプロジェクトから始めていますから、たぶんナイーブすぎるのですが、個人の庭というものは存在しないといった考えをもっているのです。

バレンハウスのような個人邸のためにデザインしたランドスケープも、より大きな場においてその考えが広まっていくと思いたいのです。ひたすらに、その土地に自生する植物だけを使うといった愚かで一般的な考え方を覆すことができますし、区画の区分を気にせずに動植物を受け入れ歓迎することができるのです。

この地域では一般的に行われていることなのですが、贅沢とは、大きな家を建てることではないのだと、他の人にも示すこともできるのです。このプロジェクトでは、小さな構造物だけではなく森林の空き地全体が家であると私たちは捉えているのです。

もうひとつは、植物そのものに関するアイデアです。熱帯地方では、植物を個々に評価するのではなくグループとして評価する傾向があるのです。 ロベルト・ブール・マルクスの作品を見てみると、彼は植物で地形を作り上げるかのようにしているのです。北の地域では季節がありますし、冬には生命のサイクルが途切れて、冬眠に入り、春になるとまた始まって植物が花を咲かせます。とても幻想的な瞬間です。北の人は、冬の間も生き続ける植物を大切に愛でているように思います。北欧のそういうところはとても好きですね。一年のある時期には、個々の植物を室内に入れて保護する必要がでてきます。外では生きられないからですね。こういった行為は植物に新たな意味を与えてくれるものです。

熱帯地方ではそのようなことはありません。むさ苦しくて退屈にも感じられます。熱帯地方の美しさはわかるのですが、無限の生命力が単調さにつながってしまうのです。物事が変化しないのです。ただ、どんどん成長して手に追えなくなっていく。生命のサイクルが途切れないためには、特定の植物が煌めくような空間を作る必要があるのです。南米の屋外庭園を設計していると、個々の植物を見分ける重要性に面白みを感じます。見分けていくためにはレイヤーを構築して、色の濃い緑を背景にする必要があるのです。その前面には例えば、ランの花をちょっとした色味のポイントとして置いたりするのです。

最近では、似た植物を扱うことにも興味があります。例えば、熱帯地方の植物に魅了されていて、それをオスロの庭にも植えたいとします。死なない植物で熱帯地方のものに似たものを探すのです。こういった方法で、異国情緒を喚起するような構成が作り出せるのです。

庭造りで難しいのは、クライアントも含めてですが、土着の植物を使うように言ってくる人に出会うことなのです。それは、私にとってチャンスの損失を意味します。自然には起きないことが起き、物事がミックスされる風景が最も美しいものだと私は思っていますから。

私たちはこのアイデアをバレンハウスで探求していきました。この住宅は、海抜2100メートルの高さにあるのですが、私たちはパラモ高原のような風景にしたいと思ったのです。そこは、標高3000メートル付近より上の生態系が保護されている場所です。本当のパラモ高原では家を建てたり個人の庭をもったりすることは許されません。それに、その生態系の中の植物をもって降りることもできません。生き延びることができないからです。ランドスケープアーキテクチャーでは、建築におけるプロポーションやマテリアルのように美学的なコードを簡単に取り入れることはできません。植物が生きるか死ぬか、なのです。無慈悲なものです。結局、私たちがやったことは、パラモ高原の植物に近い見た目のもので、海抜2100mでも育つものを選ぶことでした。標高のはるか高くにある庭がイリュージョンとして構築されたのです。いくぶんポストモダン的な庭の考え方なのかもしれませんが、本当に不思議な空間が作れるのです。ノイトラがいくつかの住宅で試していたのと同じ考え方なのです。

実際、バレンハウスを写真から特定するのはとても難しいですよね。

パラモ高原は、ある意味典型的なアルプスの風景にとても近いものがあるのです。完成直後は、この家が、ノルウェーかスイスにあるように思う人もいるでしょう。こういった不定性に非常に興味があるのです。コロンビアなのか、ノルウェーなのか、スイスなのかわからないようなね。そのためにはあらゆる状況をモデリングし直すといった包括的戦略が必要でした。

この家は森の空地にあって、そこは何世代も牛が土を踏み固めてきた場所なのです。そこに何かを植えるのはとても難しいことでした。文字通り土を取り除く必要がありました。敷地には外来植物も多く生息していたのです。

単純に庭を作ったとしても蓄牛に使われるような侵攻力の強いオーストラリアの草に飲み込まれてしまうのです。家の周囲の生物質を入れ替えて、外来種の草の残骸を燃やし、私たちがこうあるべきだと思う庭の考えに従って土壌を再構築する必要があったのです。すごく面白いのです。建築的、生物学的なコンテクストを完全に発明することが。それが作られたもので奇妙なものであったとしても、不思議なことに親しみのあるものに見えるのですから。

2022年10月7日

Luis Callejas: It was back in 2014, when Charlotte and I were about to start working together, that we got an invitation from the Los Angeles based curator Mimi Zeiger to stay a week at the VDL house and exhibit our work. It was our first project together, and the time spent at the house became an important step in plotting a new path for our office.

The VDL house was a place where the Neutras received clients, experimented with space and materials, and explored how to design modest quality, and what quality meant in the moment when ideas about luxury where changing. It was simultaneously a domestic space, a workshop, and an office - a condition and lifestyle I find very inspiring.

IT’S NOT ONLY A HOUSE, BUT ALSO A PROTOTYPE FOR FUTURE HOUSES.

You could say the VDL is a house about what’s coming next. Neutra called it a research house. I had seen this experimental approach in a few houses before, but typically experimental houses that evolve step by step have a sort of bricolage character which I am not particularly interested in.

It is important that a project has a clear intention. Although having said that, I do appreciate a dose of that ‘work-in-progress’ atmosphere, of something being tested, unfinishedness, that exploratory spirit which gives rise to a sense of openness, freedom. I guess in the right measure it looks effortless.

In our recent projects we have tried to do something similar, which is to use fragments of a house, sometimes details, as tests for future projects. To give you an example, we recently completed a house consisting of two volumes in a beautiful, sloped forest clearing. We used the same materials, the same formwork, the same details, in two houses of more or less the same surface area. We were interested in how the space feels when the only differences between the volumes is the geometry of the plan and the position of the structure in regard to the surface of the earth. One volume is elongated, another one is a square, one is half sunken, the other is elevated. The first, like a retaining wall, feels more humid in the rainy season, the other feels airier and extroverted. These two experiments are now completed and allowed us and the client to discuss how to continue with future houses in the 80-hectare plot.

The VDL house feels close to our way of making architecture, or at least to something we aspire to. It is very much a house about future commissions. Now that I think about it, the time spent there informed the recent project I just described. I remember that Sara Lorenzen and her husband David were living in the small Neutra’s guest house across the courtyard. Every day we would meet to chat in the garden, or they would invite us for coffee. I really love this idea that two strangers, friends or families can live close enough, separated only by a garden, and out of daily serendipity, have encounters or invite each other to do something together. We ended up doing the same in the houses in El Retiro - a large garden and two separate structures that allow these encounters to occur.

NEUTRA CAME FROM AUSTRIA, A NORTHERN COUNTRY, AND ENDED UP IN CALIFORNIA. YOUR PRACTICE SPANS TWO COMPLETELY DIFFERENT CLIMATIC AND GEOGRAPHIC CONDITIONS - THE WORLD OF THE NORTH AND THE WORLD OF THE SOUTH. HOW DO YOU SEE THIS DUALITY?

I was born in Colombia, and I started architecture there, deep in tropical modernism! Charlotte is from Sweden. We are a practice that, as you said, combines two different worlds. Now we are based in Oslo, which is in some ways a cultural periphery, maybe not unlike Colombia.

In our case, it is about working in the south from the north - thinking about building in the tropical Andes while living in Oslo. I dislike the myth that you do your best work when you are close to home. It has been said many times about writers writing in their own language, but place, location, climate - politic, is another story. I think that long-distance dialog is powerful and perhaps provokes something even more contextual than if it was written or designed on site.

As a matter of fact, to understand better my own condition, for years I have been interested in artists and architects that have done their very best work once they were far from home, confronted with different climates, different cultures, different vegetation. It made me think of James Joyce evoking Ireland from Zürich. Think about Jørn Utzon and Can Lis – a Nordic architect exploring the potential of living without thermal barriers. The same worked for Neutra in California after his move from Europe. These were climatically liberated architects. There are many more similar great stories one can refer to. It’s really important in our work to build these deep connexions with specific places from a distance and thinking hard about how that distance intensifies the single idea that establishes that connection in the first place.

Norway is obviously cold in the winter. When we make a project in Colombia, whilst sitting in Oslo, there’s sometimes a longing for things that you take for granted when you are in South America. This longing influences both our decision-making process and imagination. The consequent nostalgia brings out solutions that you wouldn’t come up with if you were close to the building site.

For example, I used to think that 21C degrees was cold for a house interior, and that such a house in the high-altitude Andes requires tight thermal barriers. After living in Norway, it’s become clear that it’s fine to design a house, in that context, where the windows don’t fit perfectly. I have learned that 18 degrees at night is acceptable. You just wear a sweater, and the problem is solved. Architects working at high altitudes in the tropics wouldn’t usually consider this acceptable, because for them 18C degrees is assumed too cold. The recent houses we have completed are more open and it became possible to design even the window profiles without perfectly tight thermal sealing.

WHAT CAN THE NORTH LEARN FROM THE SOUTH?

There are diverse constraints and potentials in each warm country.

In Brazil for instance, great architecture often seems effortlessly aerial, lifted with few supports, literally flying above the ground. It teaches you how to open the ground floor, how to build with only two columns aligned and never more than that. This would never work in Colombia because of earthquakes. When an earthquake hits, the lateral forces are much stronger than gravity. Consequently, architecture is about dealing with side forces, lateral vectors rather than vertical. That’s why we don’t have large cantilevers, or so much interest in the poetics of defying gravity. Colombian architecture is essentially telluric. You must also work with the complex Andean topography; sites are rarely flat. You learn to love to interpolate contours in the drawings and to start designing a house by manipulating these delicate lines. The first act of building is usually redefining the geometry of the earth, often the second act is a retaining wall.

Generally speaking, each of these southern countries have particular features, the reactions to which, can be of great inspiration in the North, where there are also mountainous regions, and densely forested landscapes.

I think the reactions to tropical conditions can inform northern architecture based on the sculptural qualities these reactions provoke. These sculptural qualities often go together with modest budgets, therefore, there has always been a restrained elegance in the use of structures, where the structure defines the expression of both outside and inside but remains modest.

WHAT WAS THE EXHIBITION YOU PREPARED IN VDL HOUSE ABOUT?

We became fascinated with the story of the relationship between the VDL house and Silver Lake Reservoir, which is essentially a large water basin the size of a small lake, a piece of infrastructure made of concrete. Nowadays, trees grow around it, and from most angles, it can indeed look like a pretty lake. Many neighbouring houses have popped-up, all orientated towards the reservoir. However, when Neutra built his house, the setting was rather different.

It was one of the first houses in the mid 1930s, that established a relationship with this artificial landscape. Neutra saw the water reservoir made of concrete as a kind of landscape entity worth orientating towards visually. He recognized its potential. He designed the reflecting water garden on the roof, which, when you sit very low in the penthouse, merges with the horizontal plane of the water in the reservoir. He designed the big glass surfaces looking in all directions, inviting what was around into the everyday domestic space. There are many devices to manipulate the views: mirrors, shadows, reflections etc. These endeavours were aimed to somehow enhance the participation of the rather reduced space of the house in an overall territorial composition. It is clear to me that he was dreaming about other houses in the future territorial ensemble that this area would become.

When we went there, there was a serious drought in L.A. and the reservoir was almost completely dry. It looked terribly strange to see all these houses stare at the big concrete concave surface. Moreover, in the VDL house, right after the renovation the water garden did not work. The views and particularly the sun’s rays were uncomfortably intense because of the huge unshaded windows. During our residency, to better understand the core intentions driving the design of the house, we felt we should add or finish what we considered either missing or incomplete.

We ended up with the idea to make new silk curtains for the roof pavilion and stage an exhibition. We assembled our diverse aquatic projects from the past, as a kind of continuous stream, which became like a single drawing and formed the design of the silk curtain. We also managed to fill the roof garden with water.

Our installation talked about the artificial water landscape, filtering the far views, lightness, pleasant shadow, and proximity of water. It told the story of the main qualities of VDL house, whilst also showing our projects which followed similar fascinations to those of Neutra.

THE HOUSE IS ALMOST LIKE A TREE. EVERY FLOOR IS DIFFERENT. YOU HAVE AN EVER-CHANGING POINT OF VIEW. WOULD YOU CALL IT AN ORGANIC DESIGN?

I wouldn’t describe it as organic; it has a thought through, rational and precise plan. I think VDL House is organic in the sense that it is not ashamed of exposing the process of its own making, its growth over time.

WHAT DEVICES DID NEUTRA USE TO GENERATE THE EFFECT OF CONTINUITY BETWEEN THE LANDSCAPE AND THE HOUSE?

First, maybe it’s important to point out that Neutra had a background in landscape architecture and town planning. He came from Europe, from Austria, passed through Switzerland and landed in subtropical California. Only there did he become the architect known for beautiful houses, but the truth is that he had worked at much larger scales. Most architects start small, and as they grow older, get larger projects. He instead, did the opposite, working first as a town planner. He also knew and liked plants, even assisting Schindler with the garden design of his houses. This background somehow manifests itself in relatively small domestic architecture - the capacity of a project speaking to a much larger context. This outlook was also expressed in his writings, notably in Survival Through Design (1954).

In every single detail, you can see that Neutra was trying to connect the small building with the large territory. The principal organisation of the plan, the roof top water garden that when sitting merges visually with the reservoir,

mirrors that would reflect elements of the landscape and project them on to the walls and floors - all these decisions were aimed at generating the feeling of inhabiting not only a house but the whole area, a much larger landscape.

WHAT ARE THE STRATEGIES YOU USE TO TURN A COMMISSION FOR A HOUSE INTO A LANDSCAPE PROJECT?

It is often our aspiration to do this. I will tell you about the pragmatic part which is something we also enjoy.

Architecture and landscape are different things, and they should remain different. On the other hand, this game about amplifying the opportunity of building, into designing an unsolicited garden fascinates us. During the planning process, at a general level, architects often make a distinction between the dry works and the wet works. The latter is a world of concrete, mixing messy powders with water, pouring structures, the former is a world of solid, precisely cut materials, fine wood, screws, finishes and so on.

I am interested in the wet works as the main gesture and expression, the structure that defines spaces.

The dry works are less interesting to me. In order to cover and refine the wet works, detailed planning is required, and a different type of qualified craftsmanship, often expensive materials, and importantly, a lot of time.

Since very early on in my career, I started to think that by skipping the dry works I could win time for inviting more interesting topics to the table, such as landscape. I realised that, if you manage to draw a building in which you redirect the time, energy, and money from the “dry works” into the landscape, into the detailing of gardens, you can simply extend the limits of your design. In other words, architecture and landscape are not the same, but good landscape can complement architecture in a better way than overly refined finishes. Why not convince a client to do a garden and forget about preconceived ideas of interior design? We are straightforward with clients; we tell them that they can do a very decent garden with the resources that would normally be used on banal interior materials.

For us, gardens offer a possibility to create something fantastic that you wouldn’t normally see, a garden can be surreal and the best complement to a rational structure. It’s not just about letting the garden enter the house. It’s not about nature vs artifact. It’s about a living fantasy - a garden is an artwork.

WITH REGARD TO GARDENING, WHAT DO YOU FIND PARTICULARLY INSPIRING?

The first thing is that, as I started with public projects, I have this perhaps naive idea that there is no such thing as a private garden.

I like to think the landscape we designed for a private house, the Ballen house, reverberates in the larger setting. It challenges this silly prevailing idea of working exclusively with native trees, and it’s free to welcomes and host fauna that does not care about the divisions between plots.

It shows others that luxury doesn’t mean building large houses, which is usually what happens in this region. For this project we see the whole forest clearing as the house, not just the small structures.

Another idea regarding the plants themselves. In the tropics, there is a tendency not to value plants individually, but more in groups. Think of Roberto Burle Marx’s work, he almost created topography with plants. In the northern locations you have seasons, the cycle of life is interrupted by winter, life enters hibernation and starts again in spring, when the plants bloom. It’s a fantastic moment. It seems to me that people in the North value and admire plants that remain alive through the winter. I like that very much about Northern Europe. At certain times of the year, you need to protect individual plants by taking them inside, because they are unable to survive outside. It gives them a new meaning.

In the tropics you don’t have that. It’s kind of oppressive and boring. I know the tropics are beautiful, but the unlimited vitality can also be too monotonous. Things don’t change. They just grow and grow and go out of control. When the cycle of life is not interrupted, you need to create the space for certain plants to shine. When I design outdoor gardens in South America, I am sometimes interested in the value of recognising individual plants. In order to do that, you need to construct layers and work with a dark green background. In front of which you can put for instance orchids as points of small colour.

Recently I am also interested in working with plants that look like other plants. Let’s say, if I’m fascinated by a plant from the tropics, that I want to put in a garden in Oslo, I’ll look for a plant that won’t die and looks like the tropical plant. In this way I can make compositions that evoke the atmosphere of different, exotic locations.

When you make gardens, one difficult thing is that you meet people, including clients, that push you to work with native plants. To me, it’s a lost opportunity. The most beautiful landscapes are mixtures of things that wouldn’t happen spontaneously in nature.

We explored this idea in our Ballen House. It’s at an altitude of 2100 metres above sea level. We wanted the landscape to look like Paramo, which is a protected ecosystem that starts high above, at around 3000 meters. Nobody will build a house or be allowed to have a private garden in a real Paramo. You cannot just bring the plants from that ecosystem down because they wouldn’t survive. In landscape architecture you cannot easily import aesthetic codes, like you do with systems of proportion or materials in architecture. Plants live or die. It’s ruthless. In the end, what we did, was to choose plants that look very close to Paramo plants and worked at 2100 m and to use them to construct the illusion of a higher altitude garden. Maybe it’s a kind of post-modern way of thinking about gardens, but it produces really magical places. It’s an idea that Neutra explored in some of his houses as well.

IT’S INDEED VERY DIFFICULT TO LOCATE BALLEN HOUSE BASED ON THE PHOTOS.

Paramo is in some ways quite close to some archetypal alpine landscapes. Some people think that the house we just completed is in Norway or maybe Switzerland. I’m very interested in that kind of ambiguity - when you cannot tell, whether it is Colombia, Norway, or Switzerland. To achieve this, it required an overall strategy of re-modelling the whole setting.

The house is in a forest clearing, where the cows had, over many generations, compacted the soil. It was very hard to plant anything there. We needed to literally remove the soil. The site also harboured many invasive plants.

We couldn’t just plant a garden because it would have been swallowed by the pre-existing aggressive Australian grass used for cattle. We had to replace all the biological matter surrounding the house, burn the remnants of local invasive grass and reconstruct the soil according to our idea of what the garden needed to become. It’s fascinating - completely inventing a context, both architectural and biological, that even if constructed and strange, looks oddly familiar.

07.10.2022

路易斯客卡列哈斯(Luis Callejas):2014年夏洛特(Charlotte)和我即将开展合作,恰逢洛杉矶策展人米米-泽格(Mimi Zeiger)邀请我们去VDL住宅小住一周,展出我们的作品。这因而成为我们合作的第一个项目,在那儿度过的时光也踏出了我们规划事务所新路线的重要一步。

VDL住宅既是诺伊特拉接待客户之处,也是对空间和材料的探索实践,并且探讨了如何设计出适度的品质,以及当奢华的定义变化时品质又意味着什么。它同时是家庭空间、工作室和办公室,我认为这是一种很具启发性的状态和生活方式。

这不仅是一座住宅,也是未来住宅的原型。

VDL住宅可称作一座关于未来的住宅。诺伊特拉称其为研究性住宅。我在一些住宅中也曾见过这类实验性方法,但典型的渐进式发展的实验性住宅会有一种混搭特征,我对这种特征兴趣寥寥。

尽管一个明确的目的对一个项目来说至关重要,但我依然很欣赏那种测试中、未完工的“半成品”腔调。它会营造一种开放自由的感觉,我想在正确的尺度下,它看起来毫不费力。

我们在最近的项目中试着做了一些类似的事,就是用住宅的片段,有时是细部,做未来项目的测试。

举例来说,我们最近在一个美丽的、有坡度的森林空地上完成了一个由两个体块组成的住宅。我们用相同的材料、相同的模架、相同的细部,建造了两座面积差不多的住宅。我们感兴趣的是,当两个建筑体块只是平面形状和与地表的位置关系不同,空间感受会是怎样。一个体块是拉长的,另一个是方形的;一个是半沉的,另一个是升高的。第一个体块就像挡土墙,在雨季会感觉更潮湿;另一个体块会感觉更通风和外向。这两个实验现在已经完成,我们得以和客户讨论如何在80公顷的地块上继续建造未来住宅。

VDL住宅感觉上与我们的做建筑的方式很接近,或者说,起码是我们所向往的那种。在很大程度上,它是一个受未来之托的住宅。此刻想来,在那里度过的时光对我刚刚提到的近期项目提供了启示。我记得萨拉-洛伦森(Sara Lorenzen)和她的丈夫大卫(David)当时住在院子对面的诺伊特拉的小客房里。每天我们都会在花园里见面聊天,或者他们邀请我们去喝咖啡。我很喜欢这个想法:两个陌生人、朋友或家庭住得很近,只隔了一座花园,出于日常的偶然性,偶遇或相约一起做些事。最终,我们在埃尔雷蒂罗(El Retiro)住宅里也做了同样的事——一座大花园和两座独立建筑,让这些邂逅得以发生。

诺伊特拉来自奥地利,一个北方国家,最后到了加利福尼亚。你的实践跨越了两种截然不同的气候和地理条件——北方世界和南方世界。你如何看待这种双重性?

我出生于哥伦比亚,并且从那里开始做建筑,深陷于热带现代主义!夏洛特来自瑞典。如你所说,我们是联合两个不同世界的一场实践。如今我们的总部设在奥斯陆,在一些方面,它是一个文化边缘地带,与哥伦比亚或许是不一样的。

在我们的例子里,这是一个自北向南的工作——身住奥斯陆的同时在思考热带安第斯山脉的建设。我不爱听的神话是:离家乡近能做出最出色的工作。说到作家用自己的母语写作,这点经常会被拿来说谈,不过说到地点、区位、气候、政治,那又是另一回事。我认为远距离对话是强大的,也许比在现场写作或设计更能激发一些背景性的东西。

其实多年来,为了更好地了解自己的状况,我一直对某些艺术家和建筑师感兴趣。他们一旦远离自己的家乡,面对不同的气候、不同的文化、不同的植被,就能完成他们最好的作品。我想到了詹姆斯-乔伊斯(James Joyce)从苏黎世唤起了爱尔兰。想到了约恩-乌特松(Jørn Utzon)和坎客利斯(Can Lis)——一位北欧的建筑师探索在没有保温屏障的情形下生活的可能性。诺伊特拉从欧洲搬到加州后,也是这样做的。这些都是得到气候解放的建筑师。此外还有很多类似的伟大事迹可做参考。在我们的工作中,远距离地与特定地点建立起深刻的联系,并深思这距离是如何在强化最初建立深刻联系的那个想法的,这真的很重要。

挪威的冬天很冷。当我们身在奥斯陆,做着一个哥伦比亚的项目,时不时会渴望那些在南美理所当然的事物。这种渴望影响着我们的决策过程和想象力。随之而来的乡愁带来了假如你在建筑工地附近就不会想到的解决方案。

例如,我曾经认为21℃对住宅的室内温度来说是很冷的,并且在高海拔的安第斯山脉的住宅需要严密的保温屏障。在挪威生活后我清晰地认识到,在那种情况下,设计一栋窗户没有完全符合保温要求的住宅也可以。我认识到18℃的夜间温度是可接受的,只是穿一件毛衣的问题。而在热带高海拔地区工作的建筑师通常不会认可和接受这点,对他们来说,18℃太冷了。我们最近完成的住宅更加开放,设计也不必给窗户配置完全的热密封。

北方能从南方学到些什么?

每个温暖的国家都有不同的限制和潜力。例如,在巴西,宏伟的建筑似乎常常毫不费力地腾空而起,用一些支撑从地面升出。它教你如何打开地面层,如何只用两根对齐的柱子来建造,以及其他许多。这在哥伦比亚是行不通的,因为有地震。当地震发生时,侧向力要比重力强得多。因此,建筑就是要处理侧向力,横向而非竖向的。这就是为什么我们没有大的悬臂,也没什么诗意的反重力的兴趣。哥伦比亚的建筑基本上是地面的。你还须与复杂的安第斯地形合作,场地很少是平的。你得学会喜欢在图纸中加入等高线,并从操纵这些微妙的线条开始设计住宅。建筑的第一步通常是重新定义地面的形状,第二步往往是挡土墙。

一般来说,这些南方国家都有显著特征,对这些特征的应对可以给北方带来很大的启发,因为北方也有山区和茂密的森林景观。

我认为对热带条件的应对可以为北方建筑提供借鉴,因为这些应对会激发雕塑般的品质。这些雕塑般的品质往往与适度的预算相伴而生,因此,在结构的使用上总有一种克制的优雅,结构决定了外部和内部的表达,但仍然是温和的。

你在VDL住宅内准备的展览是关于什么的?

我们着迷于VDL住宅和银湖水库之间的关系,银湖水库基本是一个小湖尺度的大水盆,是一块由混凝土制成的基础设施。如今,树木围绕着它生长,它确实看起来像一个美丽的湖泊。很多相邻的住宅冒了出来,都朝向水库。然而,当诺伊特拉建造他的住宅时,环境是相当不同的。

它是20世纪30年代中期的第一批住宅之一,与这个人工景观建立起一种关系。诺伊特拉认识到水库的潜力,认为混凝土制成的水库是一种值得在视觉上加以引导的景观实体。他设计了屋顶上的反射水花园,当你坐在顶楼很低的位置时,它与水库中的水面融为一体。他设计了大的玻璃表面,向各个方向看去,把周围的景色请到日常的家庭空间中。有许多装置来控制视线、镜像、阴影、反射等。这种努力旨在以某种方式加强住宅的相当小的空间在整个领域构成中的参与。在我看来,他显然是在梦想着这个地区的未来区域构成中的其他住宅。

我们去的时候,洛杉矶发生了严重的旱灾,水库几乎完全干涸。

所有这些住宅盯着大的混凝土凹面,看起来非常奇怪。此外,在VDL住宅里,刚装修完,水景花园就不工作了。因为巨大的无遮挡的窗户,视线和阳光让人感到不舒服。在我们的居住期间,为了更好地理解驱动住宅设计的核心意图,我们觉得应该增加或补全我们认为缺失或不完整的东西。

我们最终的想法是为屋顶凉亭制作新的丝绸帘幕并举办一个展览。我们集合了我们过去各种的水上项目,作为一种连续的水流,就像一张图纸,形成了丝质帘幕的设计。我们还设法使屋顶花园充满了水。

我们的装置考虑到了人工水景观,过滤了远景、亮度、令人愉悦的遮荫和水的亲近。它讲述的故事包涵了VDL住宅的主要特征,同时也展示了我们的项目,这些项目与诺伊特拉的项目有着相似的魅力。

这所住宅几乎像一棵树。每层楼都是不同的。你会有不断变化的视角。你会说这是一个有机的设计吗?

我不会把它称为有机的;因为它有一个经过深思熟虑的、合理和精确的计划。但我又认为VDL住宅是有机的,因为它不羞于暴露自己的建造过程,不羞于暴露自己随着时间的推移而成长。

诺伊特拉用什么手段来产生景观和住宅之间的连续性效果?

首先,也许有必要指出的是,诺伊特拉有景观建筑和城市规划的背景。他来自欧洲,来自奥地利,经过瑞士,在亚热带的加利福尼亚落脚。

只有在那里,他才成为以设计优美住宅而闻名的建筑师,但事实上,他曾做过更大的尺度的工作。大多数建筑师开始时项目规模不大,随着年龄的增长,会得到更大的项目。而他却相反,先做起了城市规划师。他还了解并喜欢植物,甚至协助辛德勒(Schindler)进行住宅的庭院设计。在某种程度上,这样的背景体现在相对小尺度的本土建筑中——项目与更大的环境对话的能力。这个看法也在他的著作中得到了表达,特别是在《通过设计求生存》(1954)中。

在每一个细节中,你可以看到诺伊特拉试图将小建筑与大领域联系起来。该平面的主要组织、坐着时视觉上与水库融合的屋顶水景花园,反映景观元素并将其投射到墙壁和地板上的镜子——所有这些选择都是为了营造一种栖居在场地更大景观里的感觉,而不仅仅是住在一栋住宅里。

你用什么策略来把一个住宅的委托变成一个景观项目?

做到这一点往往是我们的愿望。我将告诉你务实的部分,这也是我们喜欢的事情。

建筑和景观是不同的东西,而且它们应该保持不同。另一方面,这种关于将一个设计建筑的机会放大变成设计一个不请自来的花园的游戏让我们着迷。在规划过程中,在一般的层面上,建筑师经常对干作业和湿作业进行区分。后者是一个混凝土的世界,将混乱的粉末与水混合、浇筑结构。前者是一个固体的世界,精确切割的材料、精细的木材、螺丝、饰面等等。

我对作为主要姿态和表现的湿作业感兴趣,因为它是定义空间的结构。

干作业对我来说不那么有趣——为了覆盖和完善湿作业,需要详细规划、不同类型的品质工艺,往往用着昂贵的材料,重要的是需要大量时间。

在我职业生涯的早期,我就开始思考,通过跳过干作业,我可以赢得时间来讨论更有趣的话题,比如景观。我意识到,如果你设法画出一个建筑,把时间、精力和金钱从 "干作业 "转到景观上,转到花园的细节上,你就可以简单地扩大设计的范围。换句话说,建筑和景观是不一样的,但是好的景观可以比过于精致的装饰更好地补充建筑。为什么不说服客户做一个花园而忘了室内设计的先入为主的想法呢?我们对客户很直接;告诉他们,他们可以用通常用于平庸的室内材料的资源做一个非常体面的花园。

对我们来说,花园提供了一种可能性,可以创造出你通常不会看到的奇妙的东西,花园可以是超现实的,是对理性建筑的最好补充。这不仅仅是让花园进入住宅的问题,也不是关于自然还是人工制品,它是关乎生活的想象——花园是艺术品。

关于园艺,你觉得什么东西特别有启发性?

首先,由于我是从公共项目开始的,我有一个也许很天真的想法,即没有私人花园这回事。我想,我们为私人住宅设计的景观,如拜伦住宅(Ballen House),能在更大的环境中产生反响。它可以挑战只用本地树木的愚蠢但普遍的想法,或者它确实开始接纳和欢迎那些不受地块划分影响的动物群。

它还可以向其他人展示,奢华并不意味着建造大房子,这通常是在这个地区发生的事情。对于这个项目,我们把整个森林空地看作是住宅,而不仅仅是小小的建筑。

另一个想法关于植物本身。在热带地区,有一种趋势是不重视植物个体,而更多地将其作为群体。想想看罗伯托客布雷客马克思(Roberto Burle Marx)的作品,他几乎用植物创造了地形。在北方地区受季节影响,生命周期会被冬天打断、进入冬眠,到春天植物开花时又开始。这是一个奇妙的时刻。

在我看来,北方人重视并欣赏那些在冬季仍然活着的植物。我非常喜欢北欧的这点。在一年中的某些时候,你需要保护个别植物、把它们放在室内,因为它们在外面无法生存。这赋予了它们新的意义。

在热带地区不会有这种情况,有点压抑和无聊。我知道热带地区很美,但无限的活力也可能过于单调。事情没有变化。它们只是不断地生长,不断地壮大,不断地失去控制。当生命的循环不被打断时,你需要为某些植物创造空间,让它们大放异彩。当我在南美洲设计室外花园时,我有时对识别个别植物的价值有兴趣。为了做到这点,你需要构建层次,并以深绿色为背景开展工作。在前面,你可以把例如兰花作为小的颜色点。

最近,我还对那些看起来像其他植物的植物感兴趣。比方说,如果我对热带地区的一种植物很着迷,我想把它放在奥斯陆的一个花园里,我会寻找一种不会死的植物,而且看起来像热带植物。通过这种方式,我可以做出能唤起不同的异国情调的构图。

当你做花园的时候,有一件困难的事情是,你会遇到一些人,包括客户,他们会催促你用本土植物来工作。对我来说,这是丢掉了一次机会。最美丽的景观是自然界中不会自然发生的事物的混合体。

我们在拜伦住宅探索了这个想法。它位于海拔2100米的地方,我们希望景观看起来像帕拉莫。帕拉莫是一个受保护的生态系统,从海拔3000米左右开始。没有人会在真正的帕拉莫建住宅或被允许有一个私人花园。你不能把那个生态系统的植物带下来,因为它们无法生存。在景观中,你不可能像建筑中的比例系统或材料系统那样轻易地导入美学标准。植物的生存或死亡,是无情的。最后,我们所做的是选择与帕拉莫植物非常接近的植物,并在2100米处工作,用它们来构建一个高海拔花园的幻觉。也许这是一种关于花园的后现代思维方式,但它真的催生出很神奇的地方。这也是一个诺伊特拉在他一些住宅里探索的想法。

根据照片,要找到拜伦住宅确实非常困难。

帕拉莫在某些方面相当接近于一些典型的阿尔卑斯山景观。有些人认为,我们刚刚完成的房子是在挪威或瑞士。我对这种模糊性非常感兴趣——你无法判断它是哥伦比亚、挪威还是瑞士。为了实现这一点,需要重塑整个场景的整体策略。

房子在一片森林空地上,好几代的奶牛压实了土壤,在那种任何植物都非常困难。我们需要真正地清除土壤。这里还藏有许多入侵的植物。

我们不能只是种植一个花园,不然它会被之前用于养牛的澳洲草吞噬。我们必须替换住宅周围的所有生物物质,烧掉当地入侵草的残余部分,并根据我们对花园的想法重建土壤。这很吸引人——完全创造了一个包括建筑和生物的新环境,尽管是人工构造的、陌生的环境,但看起来异样地熟悉。

2022年10月7日

ルイス・カレジャス:2014年のことです。シャーロットと私は一緒に仕事を始めようとしていたころ、ロサンゼルスのキュレーター、ミミ・ツァイガーからの誘いで、V.D.L.ハウスに一週間滞在して作品を展示することになったのです。私たちが初めて一緒に取り組んだプロジェクトでした。この家で過ごした時間は私たちの事務所の新しい道筋への重要なステップとなりました。

V.D.L.ハウスにノイトラはクライアントを招待し、空間や素材の実験を行っていたのです。贅沢さへの考え方が変わりつつある時代の中で、慎ましさなど、どういった質が意味をもちえるのかを探求していたのです。生活空間であると同時に、作業場でもありオフィスでもありました。この状態やライフスタイルはとても刺激的に思えました。

これは単なる住宅ではなく、未来の住宅のプロトタイプなんですよね。

V.D.L.ハウスは、次世代の住宅だと言えるでしょう。ノイトラはリサーチハウスと呼んでいました。以前にもいくつかこういった実験的アプローチの住宅を見ていましたが、典型的な実験住宅は日々進化するもので、ブリコラージュ的性格があり、あまり興味を持てませんでした。

私にとっては、プロジェクトに明確な意図があることが重要なのです。とはいえ、ある程度の「ワーク・イン・プログレス」的雰囲気や試験性、それに未完成であることの良さもわかります。そういった探究心が自由で開放的な感覚を作り出してくれるものです。いい意味で力みがなく見えるのだと思います。

最新のプロジェクトでは、同じようなことを試みました。次のプロジェクトへのテストとして、断片やディテールを試してみたのです。

詳しい例をあげると、美しい森の中の傾斜をもった空き地に、二つのボリュームの住宅を完成させたのですが、同じ素材、同じ型枠、同じディテールをほぼ同じ表面積の二つの住宅に用いたのです。私たちの興味は、地表面に対する平面の幾何学、それと構造の配置の違いによって、どう空間が感じられるのか、ということでした。細長いものと正方形のもの、半分沈んでいるものと高さのあるもの。前者は擁壁のようで雨季には湿度を高く感じ、後者は風通しがよく外向的に感じられる。これら二つの実験が行われたことで、80ヘクタールある敷地に、今後どのような家を建てていくかをクライアントと話し合うことできました。

V.D.L.ハウスは私たちの建築の作り方に近いものです。少なくとも私たちの目指すものに近いと感じています。まさに将来の依頼を受けるための住宅。今思うと、そこで過ごした時間が先ほど説明したプロジェクトに影響を与えたのだと思います。サラ・ロレンゼンさんと夫のデイヴィッドさんが、中庭の向かいにある小さなノイトラのゲストハウスに住んでいたことを思い出します。私たちは毎日庭でおしゃべりをしていました。コーヒーに誘ってくれたりもしました。見知らぬ者同士や友達同士、家族同士が庭を隔てた近くに住みながら、日常のひょっとした偶然から、誘い合ったりできるこのアイデアは本当にいいですよね。結局、私たちはエル・レティロの住宅でも同じことをしていたのです。つまり、広大な庭と二つの独立した構造がこうした出会いを可能にしているのです。

ノイトラは、北の国オーストリアからやってきてカルフォルニアに移住しました。あなたの仕事は、気候や地理的条件の全く異なる北と南の世界を横断していますが、この二面性についてはどのようにお考えですか?

私はコロンビアに生まれてそこで建築をはじめました。トロピカルモダニズムのディープなところでね!シャーロットはスウェーデン出身です。私たちはあなたのおっしゃるように、二つの異なる世界を結びつけながら活動をしているのです。現在はオスロに拠点を置いていますが、ここはある意味、文化的な周縁なのです。コロンビアとは少し違う意味でね。

私たちの場合は、北から南のことを考える、つまりオスロに住みながら熱帯のアンデス山脈の建物を考えるということをやっているのです。家に近い方が最高の仕事ができる、という神話が嫌いなのです。作家が自分の言語で書くことについては、何度も言われていることです。ただ、場所やロケーション、気候、それに政治についてはまた別の話だと思います。遠距離での対話は、パワフルなもので、現場で書き物をしたりデザインしたりするよりもコンテクストに沿った何かを引き起こせると考えているのです。

実際、私自身の状況を理解するためにも、芸術家や建築家が故郷から離れ、異なる気候や文化、植生に直面したときにこそ最高の仕事を成し遂げてきた事実に長い間、関心を持っていました。ジェームス・ジョイスがチューリッヒからアイルランドを想起していたことを思い浮かべるのです。それにヨーン・ウッツォンとキャン・リス。北欧の建築家が行った気候的障壁のない生活の可能性への探求。ヨーロッパから移住してカリフォルニアにやってきたノイトラも同じですね。彼らは気候的に解放された建築家たちでした。同じような素晴らしいストーリーはまだまだたくさんあります。私たちの仕事においては、特定の場所との深い関係性を築くことがとても大事なことなのです。その場所から遠く離れながらも、その距離によって、始まりの地で生まれた一つのアイデアをいかに強化できるかを真剣に考えていくのです。

ノルウェーは冬になると当然のことながら寒いのです。オスロにいながらコロンビアのプロジェクトを進めていると、南米にいた時には当たり前だと思っていたことが懐かしく感じられることがよくあります。この懐かしさが意思決定のプロセスやイマジネーションに影響を与えます。結果としてのノスタルジーが、現場の近くにいるだけでは思い付かないような解決策を導き出すのです。

例えば以前は、21℃という温度は室内の温度としては寒いものだと思っていましたし、アンデス山脈の高地にある住宅には、しっかりとした断熱性能が必要だと考えていました。ですがノルウェーに住んで以来、そういった場所でも窓がピッタリと完璧に密閉されていなくても大丈夫だろうと思えたのです。夜は18℃でも大丈夫なのだとわかったのです。セーターを着ればそれで解決するような問題ですから。熱帯の高地で働く建築家にとっては、18℃だと寒すぎるだろうと考えてしまい許容しにくいのでしょう。最近、私たちが完成させた住宅は、もっと開放的なものですし、窓のプロファイルも完全にしっかりと密閉されたものではありません。

南の地域から北の地域が学べることはどんなことでしょうか?

温暖な国にもそれぞれ様々な制約と可能性がありますね。ブラジルの例でいえば、優れた建築は宙に浮いているものが多く、少ない支柱で地面から持ち上げられています。地上階をいかに開放するか、たった二本の柱だけで、それ以上並べずに建てるにはどうすれば良いか、といったことを教えてくれるのです。コロンビアではそうできません。地震がありますから。地震が起きると、重力よりも横方向の力の方がはるかに強く働くのです。そのため、建築は垂直方向よりも横方向の力、ベクトルに対処することが重要です。ですから、大きなキャンティレバーはありませんし、重力に逆らう詩的な表現にも、あまり興味がありません。コロンビア建築は基本的にテルリック(大地から生じた)なのです。アンデス山脈の複雑な地形にも対応しなくてはいけません。フラットな場所など、ほとんどないのです。図面の中にコンターラインを書き込んでいき、その繊細なラインを操作することから住宅をデザインしていくことの愛おしさを学んでいくのです。建築行為の第一に大地の形状を再定義し、そして次には擁壁を作ることが多いでしょうか。

一般的に南の国々にもそれぞれの特徴があります。それらに反応することは、山岳地帯や森林が密集した同じような風景をもつ北の地域にとっても大きなインスピレーションとなり得るでしょう。

熱帯的状況から生まれる彫刻的な特質は、北方の建築へも影響を与えるものだと思います。こういった彫刻的な特質には予算がかからないのです。ですから、構造体は外部と内部の表現を定義しながらも控えめな存在であり、抑制されたエレガンスを保っているのです。

V.D.L.ハウスで準備されていた展覧会はどういったものだったのでしょうか。

私たちは、V.D.L.ハウスとシルバーレイクの貯水池との関係性に魅了されていたのです。貯水池はもともと小さな湖ほどのサイズの大きな水盤であり、コンクリートでできた小さなインフラの一部なのです。今では周囲の木々も育ち、実に小綺麗な湖のように見えるのです。近隣には住宅がたくさん作られてきていて、みんな貯水池の方を向いているのです。ところがノイトラが家を建てた時には、全然違った環境でした。

この家は、人工的な風景との関係を確立した1930年代半ばにおける最初の住宅なのです。ノイトラは、コンクリートの貯水池を、視線を向ける価値のある一つの風景として捉えていました。 その可能性を認識していたのです。彼は屋根の上に反射する水庭をデザインしたのです。ペントハウスの中で腰を低く下ろすと、貯水池の水平面にその水庭が溶け込んでいくのです。大きなガラス面は四方を見渡すことができ、日常の生活空間の中に周囲の存在が巻き込まれていくようにデザインされています。眺望、鏡面、陰り、反射などを操作するための多くの工夫が施されています。いくぶん小さな住宅が、領域全体における構成へと参加できるように促す試みであるのです。将来この地域に表出してくるであろう領域的全体性の中に、他の住宅が建つことを彼が夢見ていたのは当然のことだと思うのです。

私たちが訪れた時は、ロサンゼルスは深刻な干ばつの影響で貯水池はほとんど乾いていました。

周りの全ての住宅が、巨大なコンクリートの凹みを見つめている様は、ひどく異様な光景でした。それにV.D.L.ハウスは改修直後なこともあって、水庭が機能していなかったのです。日陰のない大きな窓からの景色や、特に日差しは不快に感じるほどに強烈なものでした。私たちは滞在中に、この住宅のデザイン意図の中核を深く理解するために、足りないものや不完全なものを追加し仕上げていく必要を感じたのです。

そこで、屋上のパビリオンに新しいシルクのカーテンを作り展覧会を開くことにしたのです。私たちがこれまでに手がけた様々な水辺のプロジェクトが連続的な流れをつくり、ひとつのドローイングとして、シルクのカーテンのデザインを形成するのです。屋上の水庭に水を満たすこともできました。

私たちのインスタレーションは、人工的な水辺の風景や、霞がかかった遠くの景色、明るさや心地よい影、水の近さについて語っているのです。それはV.D.L.ハウスの特質を伝えると同時に、ノイトラに近い魅力をもった私たちのプロジェクトを紹介するものでした。

この家は木のように床のレベル差が全て異なっていますよね。視点が常に変化しているということですが、これは有機的なデザインだと呼べるものでしょうか?

有機的だとは言いませんが、考え抜かれた合理的で緻密なプランだと思います。作るプロセスや時間をかけて成長していくプロセスを恥ずかしげもなく、さらけ出しているという意味においては有機的だと思いますが。

ノイトラは風景と家の連続性を演出するために、どのような工夫をしたのでしょうか?

まず、ノイトラがランドスケープとタウンプランニングの素養をバックグラウンドに持っていたことへの指摘は重要だと思います。彼はヨーロッパのオーストリアからやってきて、スイスを経由し亜熱帯のカルフォルニアにやってきました。

そこでようやく美しい住宅で名を知られる建築家となったわけですが、実は彼はもっと大きなスケールでの仕事をしていたのです。多くの建築家は小さな仕事から始めて、歳を重ねるに連れて手がけるプロジェクトも大きくなっていくものですが、彼は逆のケースで、始めはタウンプランナーとして働いていたのです。それに植物のことが好きでよく知っていましたし、シンドラーの家の庭の設計も手伝っていたりしました。こういったバックグラウンドがどういうわけか、比較的小さな住宅建築の中にも表れてきているのです。つまり、より大きなコンテクストについても語れるプロジェクトのキャパシティがあるのです。この考えは、彼の著書である「Survival Through Design」 (1954)にも書かれています。

どんな小さなディテールからも、ノイトラがこの小さな建物を大きな領域の中に関係づけようとしていたことがわかります。この計画においての重要な構成は屋上の水庭ですよね。腰を据えるとその水庭が貯水池と視覚的に一体化し、反射面として風景の断片を反射し、壁や床に投影される。こういった判断の全ては、家の中だけに住むというのではなく領域全体の大きな風景に住むような感覚を生み出すためになされたことなのです。

住宅のプロジェクトをランドスケープのプロジェクトへと変えるためにどういった策略をとられていますか?

それは私たちの願望であることが多いですね。私たちの楽しみでもある実務的な部分についてお話ししますね。

建築とランドスケープは異なるものですし、分けて考えるべきだと思います。一方で、建築へのチャンスを、依頼もされていない庭園のデザインへと拡大していくといったこのゲームはとても楽しいものです。一般的に建築家は計画段階で、乾式か湿式かを区分していきますよね。後者はコンクリートの世界のことで、散らかった粉末を水と混ぜ合わせて構造物に流し込んでいきます。前者はソリッドな世界のことで、精密にカットされた素材や細い木材、ネジや仕上げなどのことです。

私は、主に身振りや表現としての湿式に興味があるのです。構造体が空間を定義するのです。

乾式にはそれほど興味がありません。乾式を把握して洗練させていくには、綿密な計画が必要です。それに様々な種類の的確な職人芸や、高価な材料なども必要です。それに最も重要なことは、それに多くの時間がとられてしまうことです。

私は、キャリアのかなり早い段階から、乾式の仕事を省略することでランドスケープなどのもっと興味深いトピックを議論のテーブルに持ち込む時間を確保できるだろうと考えるようになりました。「乾式」へのエネルギーと予算をランドスケープや庭のディテールに還元できるような建物を描くことができれば、単純にデザインの幅が広げられると思うのです。つまり、建築とランドスケープは同じではありませんが、良いランドスケープは過度に洗練された仕上げよりも、いい意味で建築を補完することができるのです。インテリアデザインに対する先入観を捨てて、庭に取り組むようクライアントを説得してみてはどうでしょうか?私たちは率直にクライアントに伝えていますよ。平凡な内装材に使うような資源があれば、とても立派な庭ができますよ、と。

私たちにとって庭は、普段目にできないような空想的な何かを作り出す可能性を与えてくれるものなのです。庭は超現実的なもので、合理的な構造物を補完するには最高の存在なのです。家の中に庭を入れるという話ではないですよ。自然と人工という話でもありません。それは生きたファンタジーなのです。庭は芸術なのです。

庭を造るにあたって、インスピレーションを受けるものは何ですか?

私は公共のプロジェクトから始めていますから、たぶんナイーブすぎるのですが、個人の庭というものは存在しないといった考えをもっているのです。

バレンハウスのような個人邸のためにデザインしたランドスケープも、より大きな場においてその考えが広まっていくと思いたいのです。ひたすらに、その土地に自生する植物だけを使うといった愚かで一般的な考え方を覆すことができますし、区画の区分を気にせずに動植物を受け入れ歓迎することができるのです。

この地域では一般的に行われていることなのですが、贅沢とは、大きな家を建てることではないのだと、他の人にも示すこともできるのです。このプロジェクトでは、小さな構造物だけではなく森林の空き地全体が家であると私たちは捉えているのです。

もうひとつは、植物そのものに関するアイデアです。熱帯地方では、植物を個々に評価するのではなくグループとして評価する傾向があるのです。 ロベルト・ブール・マルクスの作品を見てみると、彼は植物で地形を作り上げるかのようにしているのです。北の地域では季節がありますし、冬には生命のサイクルが途切れて、冬眠に入り、春になるとまた始まって植物が花を咲かせます。とても幻想的な瞬間です。北の人は、冬の間も生き続ける植物を大切に愛でているように思います。北欧のそういうところはとても好きですね。一年のある時期には、個々の植物を室内に入れて保護する必要がでてきます。外では生きられないからですね。こういった行為は植物に新たな意味を与えてくれるものです。

熱帯地方ではそのようなことはありません。むさ苦しくて退屈にも感じられます。熱帯地方の美しさはわかるのですが、無限の生命力が単調さにつながってしまうのです。物事が変化しないのです。ただ、どんどん成長して手に追えなくなっていく。生命のサイクルが途切れないためには、特定の植物が煌めくような空間を作る必要があるのです。南米の屋外庭園を設計していると、個々の植物を見分ける重要性に面白みを感じます。見分けていくためにはレイヤーを構築して、色の濃い緑を背景にする必要があるのです。その前面には例えば、ランの花をちょっとした色味のポイントとして置いたりするのです。

最近では、似た植物を扱うことにも興味があります。例えば、熱帯地方の植物に魅了されていて、それをオスロの庭にも植えたいとします。死なない植物で熱帯地方のものに似たものを探すのです。こういった方法で、異国情緒を喚起するような構成が作り出せるのです。

庭造りで難しいのは、クライアントも含めてですが、土着の植物を使うように言ってくる人に出会うことなのです。それは、私にとってチャンスの損失を意味します。自然には起きないことが起き、物事がミックスされる風景が最も美しいものだと私は思っていますから。

私たちはこのアイデアをバレンハウスで探求していきました。この住宅は、海抜2100メートルの高さにあるのですが、私たちはパラモ高原のような風景にしたいと思ったのです。そこは、標高3000メートル付近より上の生態系が保護されている場所です。本当のパラモ高原では家を建てたり個人の庭をもったりすることは許されません。それに、その生態系の中の植物をもって降りることもできません。生き延びることができないからです。ランドスケープアーキテクチャーでは、建築におけるプロポーションやマテリアルのように美学的なコードを簡単に取り入れることはできません。植物が生きるか死ぬか、なのです。無慈悲なものです。結局、私たちがやったことは、パラモ高原の植物に近い見た目のもので、海抜2100mでも育つものを選ぶことでした。標高のはるか高くにある庭がイリュージョンとして構築されたのです。いくぶんポストモダン的な庭の考え方なのかもしれませんが、本当に不思議な空間が作れるのです。ノイトラがいくつかの住宅で試していたのと同じ考え方なのです。

実際、バレンハウスを写真から特定するのはとても難しいですよね。

パラモ高原は、ある意味典型的なアルプスの風景にとても近いものがあるのです。完成直後は、この家が、ノルウェーかスイスにあるように思う人もいるでしょう。こういった不定性に非常に興味があるのです。コロンビアなのか、ノルウェーなのか、スイスなのかわからないようなね。そのためにはあらゆる状況をモデリングし直すといった包括的戦略が必要でした。

この家は森の空地にあって、そこは何世代も牛が土を踏み固めてきた場所なのです。そこに何かを植えるのはとても難しいことでした。文字通り土を取り除く必要がありました。敷地には外来植物も多く生息していたのです。

単純に庭を作ったとしても蓄牛に使われるような侵攻力の強いオーストラリアの草に飲み込まれてしまうのです。家の周囲の生物質を入れ替えて、外来種の草の残骸を燃やし、私たちがこうあるべきだと思う庭の考えに従って土壌を再構築する必要があったのです。すごく面白いのです。建築的、生物学的なコンテクストを完全に発明することが。それが作られたもので奇妙なものであったとしても、不思議なことに親しみのあるものに見えるのですから。

2022年10月7日

Luis Callejas: It was back in 2014, when Charlotte and I were about to start working together, that we got an invitation from the Los Angeles based curator Mimi Zeiger to stay a week at the VDL house and exhibit our work. It was our first project together, and the time spent at the house became an important step in plotting a new path for our office.

The VDL house was a place where the Neutras received clients, experimented with space and materials, and explored how to design modest quality, and what quality meant in the moment when ideas about luxury where changing. It was simultaneously a domestic space, a workshop, and an office - a condition and lifestyle I find very inspiring.

IT’S NOT ONLY A HOUSE, BUT ALSO A PROTOTYPE FOR FUTURE HOUSES.

You could say the VDL is a house about what’s coming next. Neutra called it a research house. I had seen this experimental approach in a few houses before, but typically experimental houses that evolve step by step have a sort of bricolage character which I am not particularly interested in.

It is important that a project has a clear intention. Although having said that, I do appreciate a dose of that ‘work-in-progress’ atmosphere, of something being tested, unfinishedness, that exploratory spirit which gives rise to a sense of openness, freedom. I guess in the right measure it looks effortless.

In our recent projects we have tried to do something similar, which is to use fragments of a house, sometimes details, as tests for future projects. To give you an example, we recently completed a house consisting of two volumes in a beautiful, sloped forest clearing. We used the same materials, the same formwork, the same details, in two houses of more or less the same surface area. We were interested in how the space feels when the only differences between the volumes is the geometry of the plan and the position of the structure in regard to the surface of the earth. One volume is elongated, another one is a square, one is half sunken, the other is elevated. The first, like a retaining wall, feels more humid in the rainy season, the other feels airier and extroverted. These two experiments are now completed and allowed us and the client to discuss how to continue with future houses in the 80-hectare plot.

The VDL house feels close to our way of making architecture, or at least to something we aspire to. It is very much a house about future commissions. Now that I think about it, the time spent there informed the recent project I just described. I remember that Sara Lorenzen and her husband David were living in the small Neutra’s guest house across the courtyard. Every day we would meet to chat in the garden, or they would invite us for coffee. I really love this idea that two strangers, friends or families can live close enough, separated only by a garden, and out of daily serendipity, have encounters or invite each other to do something together. We ended up doing the same in the houses in El Retiro - a large garden and two separate structures that allow these encounters to occur.

NEUTRA CAME FROM AUSTRIA, A NORTHERN COUNTRY, AND ENDED UP IN CALIFORNIA. YOUR PRACTICE SPANS TWO COMPLETELY DIFFERENT CLIMATIC AND GEOGRAPHIC CONDITIONS - THE WORLD OF THE NORTH AND THE WORLD OF THE SOUTH. HOW DO YOU SEE THIS DUALITY?

I was born in Colombia, and I started architecture there, deep in tropical modernism! Charlotte is from Sweden. We are a practice that, as you said, combines two different worlds. Now we are based in Oslo, which is in some ways a cultural periphery, maybe not unlike Colombia.

In our case, it is about working in the south from the north - thinking about building in the tropical Andes while living in Oslo. I dislike the myth that you do your best work when you are close to home. It has been said many times about writers writing in their own language, but place, location, climate - politic, is another story. I think that long-distance dialog is powerful and perhaps provokes something even more contextual than if it was written or designed on site.

As a matter of fact, to understand better my own condition, for years I have been interested in artists and architects that have done their very best work once they were far from home, confronted with different climates, different cultures, different vegetation. It made me think of James Joyce evoking Ireland from Zürich. Think about Jørn Utzon and Can Lis – a Nordic architect exploring the potential of living without thermal barriers. The same worked for Neutra in California after his move from Europe. These were climatically liberated architects. There are many more similar great stories one can refer to. It’s really important in our work to build these deep connexions with specific places from a distance and thinking hard about how that distance intensifies the single idea that establishes that connection in the first place.

Norway is obviously cold in the winter. When we make a project in Colombia, whilst sitting in Oslo, there’s sometimes a longing for things that you take for granted when you are in South America. This longing influences both our decision-making process and imagination. The consequent nostalgia brings out solutions that you wouldn’t come up with if you were close to the building site.

For example, I used to think that 21C degrees was cold for a house interior, and that such a house in the high-altitude Andes requires tight thermal barriers. After living in Norway, it’s become clear that it’s fine to design a house, in that context, where the windows don’t fit perfectly. I have learned that 18 degrees at night is acceptable. You just wear a sweater, and the problem is solved. Architects working at high altitudes in the tropics wouldn’t usually consider this acceptable, because for them 18C degrees is assumed too cold. The recent houses we have completed are more open and it became possible to design even the window profiles without perfectly tight thermal sealing.

WHAT CAN THE NORTH LEARN FROM THE SOUTH?

There are diverse constraints and potentials in each warm country.

In Brazil for instance, great architecture often seems effortlessly aerial, lifted with few supports, literally flying above the ground. It teaches you how to open the ground floor, how to build with only two columns aligned and never more than that. This would never work in Colombia because of earthquakes. When an earthquake hits, the lateral forces are much stronger than gravity. Consequently, architecture is about dealing with side forces, lateral vectors rather than vertical. That’s why we don’t have large cantilevers, or so much interest in the poetics of defying gravity. Colombian architecture is essentially telluric. You must also work with the complex Andean topography; sites are rarely flat. You learn to love to interpolate contours in the drawings and to start designing a house by manipulating these delicate lines. The first act of building is usually redefining the geometry of the earth, often the second act is a retaining wall.

Generally speaking, each of these southern countries have particular features, the reactions to which, can be of great inspiration in the North, where there are also mountainous regions, and densely forested landscapes.

I think the reactions to tropical conditions can inform northern architecture based on the sculptural qualities these reactions provoke. These sculptural qualities often go together with modest budgets, therefore, there has always been a restrained elegance in the use of structures, where the structure defines the expression of both outside and inside but remains modest.

WHAT WAS THE EXHIBITION YOU PREPARED IN VDL HOUSE ABOUT?

We became fascinated with the story of the relationship between the VDL house and Silver Lake Reservoir, which is essentially a large water basin the size of a small lake, a piece of infrastructure made of concrete. Nowadays, trees grow around it, and from most angles, it can indeed look like a pretty lake. Many neighbouring houses have popped-up, all orientated towards the reservoir. However, when Neutra built his house, the setting was rather different.

It was one of the first houses in the mid 1930s, that established a relationship with this artificial landscape. Neutra saw the water reservoir made of concrete as a kind of landscape entity worth orientating towards visually. He recognized its potential. He designed the reflecting water garden on the roof, which, when you sit very low in the penthouse, merges with the horizontal plane of the water in the reservoir. He designed the big glass surfaces looking in all directions, inviting what was around into the everyday domestic space. There are many devices to manipulate the views: mirrors, shadows, reflections etc. These endeavours were aimed to somehow enhance the participation of the rather reduced space of the house in an overall territorial composition. It is clear to me that he was dreaming about other houses in the future territorial ensemble that this area would become.

When we went there, there was a serious drought in L.A. and the reservoir was almost completely dry. It looked terribly strange to see all these houses stare at the big concrete concave surface. Moreover, in the VDL house, right after the renovation the water garden did not work. The views and particularly the sun’s rays were uncomfortably intense because of the huge unshaded windows. During our residency, to better understand the core intentions driving the design of the house, we felt we should add or finish what we considered either missing or incomplete.

We ended up with the idea to make new silk curtains for the roof pavilion and stage an exhibition. We assembled our diverse aquatic projects from the past, as a kind of continuous stream, which became like a single drawing and formed the design of the silk curtain. We also managed to fill the roof garden with water.

Our installation talked about the artificial water landscape, filtering the far views, lightness, pleasant shadow, and proximity of water. It told the story of the main qualities of VDL house, whilst also showing our projects which followed similar fascinations to those of Neutra.

THE HOUSE IS ALMOST LIKE A TREE. EVERY FLOOR IS DIFFERENT. YOU HAVE AN EVER-CHANGING POINT OF VIEW. WOULD YOU CALL IT AN ORGANIC DESIGN?

I wouldn’t describe it as organic; it has a thought through, rational and precise plan. I think VDL House is organic in the sense that it is not ashamed of exposing the process of its own making, its growth over time.

WHAT DEVICES DID NEUTRA USE TO GENERATE THE EFFECT OF CONTINUITY BETWEEN THE LANDSCAPE AND THE HOUSE?

First, maybe it’s important to point out that Neutra had a background in landscape architecture and town planning. He came from Europe, from Austria, passed through Switzerland and landed in subtropical California. Only there did he become the architect known for beautiful houses, but the truth is that he had worked at much larger scales. Most architects start small, and as they grow older, get larger projects. He instead, did the opposite, working first as a town planner. He also knew and liked plants, even assisting Schindler with the garden design of his houses. This background somehow manifests itself in relatively small domestic architecture - the capacity of a project speaking to a much larger context. This outlook was also expressed in his writings, notably in Survival Through Design (1954).

In every single detail, you can see that Neutra was trying to connect the small building with the large territory. The principal organisation of the plan, the roof top water garden that when sitting merges visually with the reservoir,

mirrors that would reflect elements of the landscape and project them on to the walls and floors - all these decisions were aimed at generating the feeling of inhabiting not only a house but the whole area, a much larger landscape.

WHAT ARE THE STRATEGIES YOU USE TO TURN A COMMISSION FOR A HOUSE INTO A LANDSCAPE PROJECT?

It is often our aspiration to do this. I will tell you about the pragmatic part which is something we also enjoy.

Architecture and landscape are different things, and they should remain different. On the other hand, this game about amplifying the opportunity of building, into designing an unsolicited garden fascinates us. During the planning process, at a general level, architects often make a distinction between the dry works and the wet works. The latter is a world of concrete, mixing messy powders with water, pouring structures, the former is a world of solid, precisely cut materials, fine wood, screws, finishes and so on.

I am interested in the wet works as the main gesture and expression, the structure that defines spaces.

The dry works are less interesting to me. In order to cover and refine the wet works, detailed planning is required, and a different type of qualified craftsmanship, often expensive materials, and importantly, a lot of time.

Since very early on in my career, I started to think that by skipping the dry works I could win time for inviting more interesting topics to the table, such as landscape. I realised that, if you manage to draw a building in which you redirect the time, energy, and money from the “dry works” into the landscape, into the detailing of gardens, you can simply extend the limits of your design. In other words, architecture and landscape are not the same, but good landscape can complement architecture in a better way than overly refined finishes. Why not convince a client to do a garden and forget about preconceived ideas of interior design? We are straightforward with clients; we tell them that they can do a very decent garden with the resources that would normally be used on banal interior materials.

For us, gardens offer a possibility to create something fantastic that you wouldn’t normally see, a garden can be surreal and the best complement to a rational structure. It’s not just about letting the garden enter the house. It’s not about nature vs artifact. It’s about a living fantasy - a garden is an artwork.

WITH REGARD TO GARDENING, WHAT DO YOU FIND PARTICULARLY INSPIRING?

The first thing is that, as I started with public projects, I have this perhaps naive idea that there is no such thing as a private garden.

I like to think the landscape we designed for a private house, the Ballen house, reverberates in the larger setting. It challenges this silly prevailing idea of working exclusively with native trees, and it’s free to welcomes and host fauna that does not care about the divisions between plots.

It shows others that luxury doesn’t mean building large houses, which is usually what happens in this region. For this project we see the whole forest clearing as the house, not just the small structures.

Another idea regarding the plants themselves. In the tropics, there is a tendency not to value plants individually, but more in groups. Think of Roberto Burle Marx’s work, he almost created topography with plants. In the northern locations you have seasons, the cycle of life is interrupted by winter, life enters hibernation and starts again in spring, when the plants bloom. It’s a fantastic moment. It seems to me that people in the North value and admire plants that remain alive through the winter. I like that very much about Northern Europe. At certain times of the year, you need to protect individual plants by taking them inside, because they are unable to survive outside. It gives them a new meaning.

In the tropics you don’t have that. It’s kind of oppressive and boring. I know the tropics are beautiful, but the unlimited vitality can also be too monotonous. Things don’t change. They just grow and grow and go out of control. When the cycle of life is not interrupted, you need to create the space for certain plants to shine. When I design outdoor gardens in South America, I am sometimes interested in the value of recognising individual plants. In order to do that, you need to construct layers and work with a dark green background. In front of which you can put for instance orchids as points of small colour.

Recently I am also interested in working with plants that look like other plants. Let’s say, if I’m fascinated by a plant from the tropics, that I want to put in a garden in Oslo, I’ll look for a plant that won’t die and looks like the tropical plant. In this way I can make compositions that evoke the atmosphere of different, exotic locations.

When you make gardens, one difficult thing is that you meet people, including clients, that push you to work with native plants. To me, it’s a lost opportunity. The most beautiful landscapes are mixtures of things that wouldn’t happen spontaneously in nature.

We explored this idea in our Ballen House. It’s at an altitude of 2100 metres above sea level. We wanted the landscape to look like Paramo, which is a protected ecosystem that starts high above, at around 3000 meters. Nobody will build a house or be allowed to have a private garden in a real Paramo. You cannot just bring the plants from that ecosystem down because they wouldn’t survive. In landscape architecture you cannot easily import aesthetic codes, like you do with systems of proportion or materials in architecture. Plants live or die. It’s ruthless. In the end, what we did, was to choose plants that look very close to Paramo plants and worked at 2100 m and to use them to construct the illusion of a higher altitude garden. Maybe it’s a kind of post-modern way of thinking about gardens, but it produces really magical places. It’s an idea that Neutra explored in some of his houses as well.

IT’S INDEED VERY DIFFICULT TO LOCATE BALLEN HOUSE BASED ON THE PHOTOS.

Paramo is in some ways quite close to some archetypal alpine landscapes. Some people think that the house we just completed is in Norway or maybe Switzerland. I’m very interested in that kind of ambiguity - when you cannot tell, whether it is Colombia, Norway, or Switzerland. To achieve this, it required an overall strategy of re-modelling the whole setting.

The house is in a forest clearing, where the cows had, over many generations, compacted the soil. It was very hard to plant anything there. We needed to literally remove the soil. The site also harboured many invasive plants.

We couldn’t just plant a garden because it would have been swallowed by the pre-existing aggressive Australian grass used for cattle. We had to replace all the biological matter surrounding the house, burn the remnants of local invasive grass and reconstruct the soil according to our idea of what the garden needed to become. It’s fascinating - completely inventing a context, both architectural and biological, that even if constructed and strange, looks oddly familiar.

07.10.2022

路易斯客卡列哈斯(Luis Callejas):2014年夏洛特(Charlotte)和我即将开展合作,恰逢洛杉矶策展人米米-泽格(Mimi Zeiger)邀请我们去VDL住宅小住一周,展出我们的作品。这因而成为我们合作的第一个项目,在那儿度过的时光也踏出了我们规划事务所新路线的重要一步。

VDL住宅既是诺伊特拉接待客户之处,也是对空间和材料的探索实践,并且探讨了如何设计出适度的品质,以及当奢华的定义变化时品质又意味着什么。它同时是家庭空间、工作室和办公室,我认为这是一种很具启发性的状态和生活方式。

这不仅是一座住宅,也是未来住宅的原型。

VDL住宅可称作一座关于未来的住宅。诺伊特拉称其为研究性住宅。我在一些住宅中也曾见过这类实验性方法,但典型的渐进式发展的实验性住宅会有一种混搭特征,我对这种特征兴趣寥寥。

尽管一个明确的目的对一个项目来说至关重要,但我依然很欣赏那种测试中、未完工的“半成品”腔调。它会营造一种开放自由的感觉,我想在正确的尺度下,它看起来毫不费力。

我们在最近的项目中试着做了一些类似的事,就是用住宅的片段,有时是细部,做未来项目的测试。

举例来说,我们最近在一个美丽的、有坡度的森林空地上完成了一个由两个体块组成的住宅。我们用相同的材料、相同的模架、相同的细部,建造了两座面积差不多的住宅。我们感兴趣的是,当两个建筑体块只是平面形状和与地表的位置关系不同,空间感受会是怎样。一个体块是拉长的,另一个是方形的;一个是半沉的,另一个是升高的。第一个体块就像挡土墙,在雨季会感觉更潮湿;另一个体块会感觉更通风和外向。这两个实验现在已经完成,我们得以和客户讨论如何在80公顷的地块上继续建造未来住宅。

VDL住宅感觉上与我们的做建筑的方式很接近,或者说,起码是我们所向往的那种。在很大程度上,它是一个受未来之托的住宅。此刻想来,在那里度过的时光对我刚刚提到的近期项目提供了启示。我记得萨拉-洛伦森(Sara Lorenzen)和她的丈夫大卫(David)当时住在院子对面的诺伊特拉的小客房里。每天我们都会在花园里见面聊天,或者他们邀请我们去喝咖啡。我很喜欢这个想法:两个陌生人、朋友或家庭住得很近,只隔了一座花园,出于日常的偶然性,偶遇或相约一起做些事。最终,我们在埃尔雷蒂罗(El Retiro)住宅里也做了同样的事——一座大花园和两座独立建筑,让这些邂逅得以发生。

诺伊特拉来自奥地利,一个北方国家,最后到了加利福尼亚。你的实践跨越了两种截然不同的气候和地理条件——北方世界和南方世界。你如何看待这种双重性?

我出生于哥伦比亚,并且从那里开始做建筑,深陷于热带现代主义!夏洛特来自瑞典。如你所说,我们是联合两个不同世界的一场实践。如今我们的总部设在奥斯陆,在一些方面,它是一个文化边缘地带,与哥伦比亚或许是不一样的。

在我们的例子里,这是一个自北向南的工作——身住奥斯陆的同时在思考热带安第斯山脉的建设。我不爱听的神话是:离家乡近能做出最出色的工作。说到作家用自己的母语写作,这点经常会被拿来说谈,不过说到地点、区位、气候、政治,那又是另一回事。我认为远距离对话是强大的,也许比在现场写作或设计更能激发一些背景性的东西。

其实多年来,为了更好地了解自己的状况,我一直对某些艺术家和建筑师感兴趣。他们一旦远离自己的家乡,面对不同的气候、不同的文化、不同的植被,就能完成他们最好的作品。我想到了詹姆斯-乔伊斯(James Joyce)从苏黎世唤起了爱尔兰。想到了约恩-乌特松(Jørn Utzon)和坎客利斯(Can Lis)——一位北欧的建筑师探索在没有保温屏障的情形下生活的可能性。诺伊特拉从欧洲搬到加州后,也是这样做的。这些都是得到气候解放的建筑师。此外还有很多类似的伟大事迹可做参考。在我们的工作中,远距离地与特定地点建立起深刻的联系,并深思这距离是如何在强化最初建立深刻联系的那个想法的,这真的很重要。

挪威的冬天很冷。当我们身在奥斯陆,做着一个哥伦比亚的项目,时不时会渴望那些在南美理所当然的事物。这种渴望影响着我们的决策过程和想象力。随之而来的乡愁带来了假如你在建筑工地附近就不会想到的解决方案。

例如,我曾经认为21℃对住宅的室内温度来说是很冷的,并且在高海拔的安第斯山脉的住宅需要严密的保温屏障。在挪威生活后我清晰地认识到,在那种情况下,设计一栋窗户没有完全符合保温要求的住宅也可以。我认识到18℃的夜间温度是可接受的,只是穿一件毛衣的问题。而在热带高海拔地区工作的建筑师通常不会认可和接受这点,对他们来说,18℃太冷了。我们最近完成的住宅更加开放,设计也不必给窗户配置完全的热密封。

北方能从南方学到些什么?

每个温暖的国家都有不同的限制和潜力。例如,在巴西,宏伟的建筑似乎常常毫不费力地腾空而起,用一些支撑从地面升出。它教你如何打开地面层,如何只用两根对齐的柱子来建造,以及其他许多。这在哥伦比亚是行不通的,因为有地震。当地震发生时,侧向力要比重力强得多。因此,建筑就是要处理侧向力,横向而非竖向的。这就是为什么我们没有大的悬臂,也没什么诗意的反重力的兴趣。哥伦比亚的建筑基本上是地面的。你还须与复杂的安第斯地形合作,场地很少是平的。你得学会喜欢在图纸中加入等高线,并从操纵这些微妙的线条开始设计住宅。建筑的第一步通常是重新定义地面的形状,第二步往往是挡土墙。

一般来说,这些南方国家都有显著特征,对这些特征的应对可以给北方带来很大的启发,因为北方也有山区和茂密的森林景观。

我认为对热带条件的应对可以为北方建筑提供借鉴,因为这些应对会激发雕塑般的品质。这些雕塑般的品质往往与适度的预算相伴而生,因此,在结构的使用上总有一种克制的优雅,结构决定了外部和内部的表达,但仍然是温和的。

你在VDL住宅内准备的展览是关于什么的?

我们着迷于VDL住宅和银湖水库之间的关系,银湖水库基本是一个小湖尺度的大水盆,是一块由混凝土制成的基础设施。如今,树木围绕着它生长,它确实看起来像一个美丽的湖泊。很多相邻的住宅冒了出来,都朝向水库。然而,当诺伊特拉建造他的住宅时,环境是相当不同的。

它是20世纪30年代中期的第一批住宅之一,与这个人工景观建立起一种关系。诺伊特拉认识到水库的潜力,认为混凝土制成的水库是一种值得在视觉上加以引导的景观实体。他设计了屋顶上的反射水花园,当你坐在顶楼很低的位置时,它与水库中的水面融为一体。他设计了大的玻璃表面,向各个方向看去,把周围的景色请到日常的家庭空间中。有许多装置来控制视线、镜像、阴影、反射等。这种努力旨在以某种方式加强住宅的相当小的空间在整个领域构成中的参与。在我看来,他显然是在梦想着这个地区的未来区域构成中的其他住宅。

我们去的时候,洛杉矶发生了严重的旱灾,水库几乎完全干涸。

所有这些住宅盯着大的混凝土凹面,看起来非常奇怪。此外,在VDL住宅里,刚装修完,水景花园就不工作了。因为巨大的无遮挡的窗户,视线和阳光让人感到不舒服。在我们的居住期间,为了更好地理解驱动住宅设计的核心意图,我们觉得应该增加或补全我们认为缺失或不完整的东西。

我们最终的想法是为屋顶凉亭制作新的丝绸帘幕并举办一个展览。我们集合了我们过去各种的水上项目,作为一种连续的水流,就像一张图纸,形成了丝质帘幕的设计。我们还设法使屋顶花园充满了水。

我们的装置考虑到了人工水景观,过滤了远景、亮度、令人愉悦的遮荫和水的亲近。它讲述的故事包涵了VDL住宅的主要特征,同时也展示了我们的项目,这些项目与诺伊特拉的项目有着相似的魅力。

这所住宅几乎像一棵树。每层楼都是不同的。你会有不断变化的视角。你会说这是一个有机的设计吗?

我不会把它称为有机的;因为它有一个经过深思熟虑的、合理和精确的计划。但我又认为VDL住宅是有机的,因为它不羞于暴露自己的建造过程,不羞于暴露自己随着时间的推移而成长。

诺伊特拉用什么手段来产生景观和住宅之间的连续性效果?

首先,也许有必要指出的是,诺伊特拉有景观建筑和城市规划的背景。他来自欧洲,来自奥地利,经过瑞士,在亚热带的加利福尼亚落脚。

只有在那里,他才成为以设计优美住宅而闻名的建筑师,但事实上,他曾做过更大的尺度的工作。大多数建筑师开始时项目规模不大,随着年龄的增长,会得到更大的项目。而他却相反,先做起了城市规划师。他还了解并喜欢植物,甚至协助辛德勒(Schindler)进行住宅的庭院设计。在某种程度上,这样的背景体现在相对小尺度的本土建筑中——项目与更大的环境对话的能力。这个看法也在他的著作中得到了表达,特别是在《通过设计求生存》(1954)中。

在每一个细节中,你可以看到诺伊特拉试图将小建筑与大领域联系起来。该平面的主要组织、坐着时视觉上与水库融合的屋顶水景花园,反映景观元素并将其投射到墙壁和地板上的镜子——所有这些选择都是为了营造一种栖居在场地更大景观里的感觉,而不仅仅是住在一栋住宅里。

你用什么策略来把一个住宅的委托变成一个景观项目?

做到这一点往往是我们的愿望。我将告诉你务实的部分,这也是我们喜欢的事情。

建筑和景观是不同的东西,而且它们应该保持不同。另一方面,这种关于将一个设计建筑的机会放大变成设计一个不请自来的花园的游戏让我们着迷。在规划过程中,在一般的层面上,建筑师经常对干作业和湿作业进行区分。后者是一个混凝土的世界,将混乱的粉末与水混合、浇筑结构。前者是一个固体的世界,精确切割的材料、精细的木材、螺丝、饰面等等。

我对作为主要姿态和表现的湿作业感兴趣,因为它是定义空间的结构。

干作业对我来说不那么有趣——为了覆盖和完善湿作业,需要详细规划、不同类型的品质工艺,往往用着昂贵的材料,重要的是需要大量时间。

在我职业生涯的早期,我就开始思考,通过跳过干作业,我可以赢得时间来讨论更有趣的话题,比如景观。我意识到,如果你设法画出一个建筑,把时间、精力和金钱从 "干作业 "转到景观上,转到花园的细节上,你就可以简单地扩大设计的范围。换句话说,建筑和景观是不一样的,但是好的景观可以比过于精致的装饰更好地补充建筑。为什么不说服客户做一个花园而忘了室内设计的先入为主的想法呢?我们对客户很直接;告诉他们,他们可以用通常用于平庸的室内材料的资源做一个非常体面的花园。

对我们来说,花园提供了一种可能性,可以创造出你通常不会看到的奇妙的东西,花园可以是超现实的,是对理性建筑的最好补充。这不仅仅是让花园进入住宅的问题,也不是关于自然还是人工制品,它是关乎生活的想象——花园是艺术品。

关于园艺,你觉得什么东西特别有启发性?

首先,由于我是从公共项目开始的,我有一个也许很天真的想法,即没有私人花园这回事。我想,我们为私人住宅设计的景观,如拜伦住宅(Ballen House),能在更大的环境中产生反响。它可以挑战只用本地树木的愚蠢但普遍的想法,或者它确实开始接纳和欢迎那些不受地块划分影响的动物群。

它还可以向其他人展示,奢华并不意味着建造大房子,这通常是在这个地区发生的事情。对于这个项目,我们把整个森林空地看作是住宅,而不仅仅是小小的建筑。

另一个想法关于植物本身。在热带地区,有一种趋势是不重视植物个体,而更多地将其作为群体。想想看罗伯托客布雷客马克思(Roberto Burle Marx)的作品,他几乎用植物创造了地形。在北方地区受季节影响,生命周期会被冬天打断、进入冬眠,到春天植物开花时又开始。这是一个奇妙的时刻。

在我看来,北方人重视并欣赏那些在冬季仍然活着的植物。我非常喜欢北欧的这点。在一年中的某些时候,你需要保护个别植物、把它们放在室内,因为它们在外面无法生存。这赋予了它们新的意义。

在热带地区不会有这种情况,有点压抑和无聊。我知道热带地区很美,但无限的活力也可能过于单调。事情没有变化。它们只是不断地生长,不断地壮大,不断地失去控制。当生命的循环不被打断时,你需要为某些植物创造空间,让它们大放异彩。当我在南美洲设计室外花园时,我有时对识别个别植物的价值有兴趣。为了做到这点,你需要构建层次,并以深绿色为背景开展工作。在前面,你可以把例如兰花作为小的颜色点。

最近,我还对那些看起来像其他植物的植物感兴趣。比方说,如果我对热带地区的一种植物很着迷,我想把它放在奥斯陆的一个花园里,我会寻找一种不会死的植物,而且看起来像热带植物。通过这种方式,我可以做出能唤起不同的异国情调的构图。

当你做花园的时候,有一件困难的事情是,你会遇到一些人,包括客户,他们会催促你用本土植物来工作。对我来说,这是丢掉了一次机会。最美丽的景观是自然界中不会自然发生的事物的混合体。

我们在拜伦住宅探索了这个想法。它位于海拔2100米的地方,我们希望景观看起来像帕拉莫。帕拉莫是一个受保护的生态系统,从海拔3000米左右开始。没有人会在真正的帕拉莫建住宅或被允许有一个私人花园。你不能把那个生态系统的植物带下来,因为它们无法生存。在景观中,你不可能像建筑中的比例系统或材料系统那样轻易地导入美学标准。植物的生存或死亡,是无情的。最后,我们所做的是选择与帕拉莫植物非常接近的植物,并在2100米处工作,用它们来构建一个高海拔花园的幻觉。也许这是一种关于花园的后现代思维方式,但它真的催生出很神奇的地方。这也是一个诺伊特拉在他一些住宅里探索的想法。

根据照片,要找到拜伦住宅确实非常困难。

帕拉莫在某些方面相当接近于一些典型的阿尔卑斯山景观。有些人认为,我们刚刚完成的房子是在挪威或瑞士。我对这种模糊性非常感兴趣——你无法判断它是哥伦比亚、挪威还是瑞士。为了实现这一点,需要重塑整个场景的整体策略。

房子在一片森林空地上,好几代的奶牛压实了土壤,在那种任何植物都非常困难。我们需要真正地清除土壤。这里还藏有许多入侵的植物。

我们不能只是种植一个花园,不然它会被之前用于养牛的澳洲草吞噬。我们必须替换住宅周围的所有生物物质,烧掉当地入侵草的残余部分,并根据我们对花园的想法重建土壤。这很吸引人——完全创造了一个包括建筑和生物的新环境,尽管是人工构造的、陌生的环境,但看起来异样地熟悉。

2022年10月7日

ルイス・カレジャス:2014年のことです。シャーロットと私は一緒に仕事を始めようとしていたころ、ロサンゼルスのキュレーター、ミミ・ツァイガーからの誘いで、V.D.L.ハウスに一週間滞在して作品を展示することになったのです。私たちが初めて一緒に取り組んだプロジェクトでした。この家で過ごした時間は私たちの事務所の新しい道筋への重要なステップとなりました。

V.D.L.ハウスにノイトラはクライアントを招待し、空間や素材の実験を行っていたのです。贅沢さへの考え方が変わりつつある時代の中で、慎ましさなど、どういった質が意味をもちえるのかを探求していたのです。生活空間であると同時に、作業場でもありオフィスでもありました。この状態やライフスタイルはとても刺激的に思えました。

これは単なる住宅ではなく、未来の住宅のプロトタイプなんですよね。

V.D.L.ハウスは、次世代の住宅だと言えるでしょう。ノイトラはリサーチハウスと呼んでいました。以前にもいくつかこういった実験的アプローチの住宅を見ていましたが、典型的な実験住宅は日々進化するもので、ブリコラージュ的性格があり、あまり興味を持てませんでした。

私にとっては、プロジェクトに明確な意図があることが重要なのです。とはいえ、ある程度の「ワーク・イン・プログレス」的雰囲気や試験性、それに未完成であることの良さもわかります。そういった探究心が自由で開放的な感覚を作り出してくれるものです。いい意味で力みがなく見えるのだと思います。

最新のプロジェクトでは、同じようなことを試みました。次のプロジェクトへのテストとして、断片やディテールを試してみたのです。

詳しい例をあげると、美しい森の中の傾斜をもった空き地に、二つのボリュームの住宅を完成させたのですが、同じ素材、同じ型枠、同じディテールをほぼ同じ表面積の二つの住宅に用いたのです。私たちの興味は、地表面に対する平面の幾何学、それと構造の配置の違いによって、どう空間が感じられるのか、ということでした。細長いものと正方形のもの、半分沈んでいるものと高さのあるもの。前者は擁壁のようで雨季には湿度を高く感じ、後者は風通しがよく外向的に感じられる。これら二つの実験が行われたことで、80ヘクタールある敷地に、今後どのような家を建てていくかをクライアントと話し合うことできました。

V.D.L.ハウスは私たちの建築の作り方に近いものです。少なくとも私たちの目指すものに近いと感じています。まさに将来の依頼を受けるための住宅。今思うと、そこで過ごした時間が先ほど説明したプロジェクトに影響を与えたのだと思います。サラ・ロレンゼンさんと夫のデイヴィッドさんが、中庭の向かいにある小さなノイトラのゲストハウスに住んでいたことを思い出します。私たちは毎日庭でおしゃべりをしていました。コーヒーに誘ってくれたりもしました。見知らぬ者同士や友達同士、家族同士が庭を隔てた近くに住みながら、日常のひょっとした偶然から、誘い合ったりできるこのアイデアは本当にいいですよね。結局、私たちはエル・レティロの住宅でも同じことをしていたのです。つまり、広大な庭と二つの独立した構造がこうした出会いを可能にしているのです。

ノイトラは、北の国オーストリアからやってきてカルフォルニアに移住しました。あなたの仕事は、気候や地理的条件の全く異なる北と南の世界を横断していますが、この二面性についてはどのようにお考えですか?

私はコロンビアに生まれてそこで建築をはじめました。トロピカルモダニズムのディープなところでね!シャーロットはスウェーデン出身です。私たちはあなたのおっしゃるように、二つの異なる世界を結びつけながら活動をしているのです。現在はオスロに拠点を置いていますが、ここはある意味、文化的な周縁なのです。コロンビアとは少し違う意味でね。

私たちの場合は、北から南のことを考える、つまりオスロに住みながら熱帯のアンデス山脈の建物を考えるということをやっているのです。家に近い方が最高の仕事ができる、という神話が嫌いなのです。作家が自分の言語で書くことについては、何度も言われていることです。ただ、場所やロケーション、気候、それに政治についてはまた別の話だと思います。遠距離での対話は、パワフルなもので、現場で書き物をしたりデザインしたりするよりもコンテクストに沿った何かを引き起こせると考えているのです。

実際、私自身の状況を理解するためにも、芸術家や建築家が故郷から離れ、異なる気候や文化、植生に直面したときにこそ最高の仕事を成し遂げてきた事実に長い間、関心を持っていました。ジェームス・ジョイスがチューリッヒからアイルランドを想起していたことを思い浮かべるのです。それにヨーン・ウッツォンとキャン・リス。北欧の建築家が行った気候的障壁のない生活の可能性への探求。ヨーロッパから移住してカリフォルニアにやってきたノイトラも同じですね。彼らは気候的に解放された建築家たちでした。同じような素晴らしいストーリーはまだまだたくさんあります。私たちの仕事においては、特定の場所との深い関係性を築くことがとても大事なことなのです。その場所から遠く離れながらも、その距離によって、始まりの地で生まれた一つのアイデアをいかに強化できるかを真剣に考えていくのです。

ノルウェーは冬になると当然のことながら寒いのです。オスロにいながらコロンビアのプロジェクトを進めていると、南米にいた時には当たり前だと思っていたことが懐かしく感じられることがよくあります。この懐かしさが意思決定のプロセスやイマジネーションに影響を与えます。結果としてのノスタルジーが、現場の近くにいるだけでは思い付かないような解決策を導き出すのです。

例えば以前は、21℃という温度は室内の温度としては寒いものだと思っていましたし、アンデス山脈の高地にある住宅には、しっかりとした断熱性能が必要だと考えていました。ですがノルウェーに住んで以来、そういった場所でも窓がピッタリと完璧に密閉されていなくても大丈夫だろうと思えたのです。夜は18℃でも大丈夫なのだとわかったのです。セーターを着ればそれで解決するような問題ですから。熱帯の高地で働く建築家にとっては、18℃だと寒すぎるだろうと考えてしまい許容しにくいのでしょう。最近、私たちが完成させた住宅は、もっと開放的なものですし、窓のプロファイルも完全にしっかりと密閉されたものではありません。

南の地域から北の地域が学べることはどんなことでしょうか?

温暖な国にもそれぞれ様々な制約と可能性がありますね。ブラジルの例でいえば、優れた建築は宙に浮いているものが多く、少ない支柱で地面から持ち上げられています。地上階をいかに開放するか、たった二本の柱だけで、それ以上並べずに建てるにはどうすれば良いか、といったことを教えてくれるのです。コロンビアではそうできません。地震がありますから。地震が起きると、重力よりも横方向の力の方がはるかに強く働くのです。そのため、建築は垂直方向よりも横方向の力、ベクトルに対処することが重要です。ですから、大きなキャンティレバーはありませんし、重力に逆らう詩的な表現にも、あまり興味がありません。コロンビア建築は基本的にテルリック(大地から生じた)なのです。アンデス山脈の複雑な地形にも対応しなくてはいけません。フラットな場所など、ほとんどないのです。図面の中にコンターラインを書き込んでいき、その繊細なラインを操作することから住宅をデザインしていくことの愛おしさを学んでいくのです。建築行為の第一に大地の形状を再定義し、そして次には擁壁を作ることが多いでしょうか。

一般的に南の国々にもそれぞれの特徴があります。それらに反応することは、山岳地帯や森林が密集した同じような風景をもつ北の地域にとっても大きなインスピレーションとなり得るでしょう。

熱帯的状況から生まれる彫刻的な特質は、北方の建築へも影響を与えるものだと思います。こういった彫刻的な特質には予算がかからないのです。ですから、構造体は外部と内部の表現を定義しながらも控えめな存在であり、抑制されたエレガンスを保っているのです。

V.D.L.ハウスで準備されていた展覧会はどういったものだったのでしょうか。

私たちは、V.D.L.ハウスとシルバーレイクの貯水池との関係性に魅了されていたのです。貯水池はもともと小さな湖ほどのサイズの大きな水盤であり、コンクリートでできた小さなインフラの一部なのです。今では周囲の木々も育ち、実に小綺麗な湖のように見えるのです。近隣には住宅がたくさん作られてきていて、みんな貯水池の方を向いているのです。ところがノイトラが家を建てた時には、全然違った環境でした。

この家は、人工的な風景との関係を確立した1930年代半ばにおける最初の住宅なのです。ノイトラは、コンクリートの貯水池を、視線を向ける価値のある一つの風景として捉えていました。 その可能性を認識していたのです。彼は屋根の上に反射する水庭をデザインしたのです。ペントハウスの中で腰を低く下ろすと、貯水池の水平面にその水庭が溶け込んでいくのです。大きなガラス面は四方を見渡すことができ、日常の生活空間の中に周囲の存在が巻き込まれていくようにデザインされています。眺望、鏡面、陰り、反射などを操作するための多くの工夫が施されています。いくぶん小さな住宅が、領域全体における構成へと参加できるように促す試みであるのです。将来この地域に表出してくるであろう領域的全体性の中に、他の住宅が建つことを彼が夢見ていたのは当然のことだと思うのです。

私たちが訪れた時は、ロサンゼルスは深刻な干ばつの影響で貯水池はほとんど乾いていました。

周りの全ての住宅が、巨大なコンクリートの凹みを見つめている様は、ひどく異様な光景でした。それにV.D.L.ハウスは改修直後なこともあって、水庭が機能していなかったのです。日陰のない大きな窓からの景色や、特に日差しは不快に感じるほどに強烈なものでした。私たちは滞在中に、この住宅のデザイン意図の中核を深く理解するために、足りないものや不完全なものを追加し仕上げていく必要を感じたのです。

そこで、屋上のパビリオンに新しいシルクのカーテンを作り展覧会を開くことにしたのです。私たちがこれまでに手がけた様々な水辺のプロジェクトが連続的な流れをつくり、ひとつのドローイングとして、シルクのカーテンのデザインを形成するのです。屋上の水庭に水を満たすこともできました。

私たちのインスタレーションは、人工的な水辺の風景や、霞がかかった遠くの景色、明るさや心地よい影、水の近さについて語っているのです。それはV.D.L.ハウスの特質を伝えると同時に、ノイトラに近い魅力をもった私たちのプロジェクトを紹介するものでした。

この家は木のように床のレベル差が全て異なっていますよね。視点が常に変化しているということですが、これは有機的なデザインだと呼べるものでしょうか?

有機的だとは言いませんが、考え抜かれた合理的で緻密なプランだと思います。作るプロセスや時間をかけて成長していくプロセスを恥ずかしげもなく、さらけ出しているという意味においては有機的だと思いますが。

ノイトラは風景と家の連続性を演出するために、どのような工夫をしたのでしょうか?

まず、ノイトラがランドスケープとタウンプランニングの素養をバックグラウンドに持っていたことへの指摘は重要だと思います。彼はヨーロッパのオーストリアからやってきて、スイスを経由し亜熱帯のカルフォルニアにやってきました。

そこでようやく美しい住宅で名を知られる建築家となったわけですが、実は彼はもっと大きなスケールでの仕事をしていたのです。多くの建築家は小さな仕事から始めて、歳を重ねるに連れて手がけるプロジェクトも大きくなっていくものですが、彼は逆のケースで、始めはタウンプランナーとして働いていたのです。それに植物のことが好きでよく知っていましたし、シンドラーの家の庭の設計も手伝っていたりしました。こういったバックグラウンドがどういうわけか、比較的小さな住宅建築の中にも表れてきているのです。つまり、より大きなコンテクストについても語れるプロジェクトのキャパシティがあるのです。この考えは、彼の著書である「Survival Through Design」 (1954)にも書かれています。

どんな小さなディテールからも、ノイトラがこの小さな建物を大きな領域の中に関係づけようとしていたことがわかります。この計画においての重要な構成は屋上の水庭ですよね。腰を据えるとその水庭が貯水池と視覚的に一体化し、反射面として風景の断片を反射し、壁や床に投影される。こういった判断の全ては、家の中だけに住むというのではなく領域全体の大きな風景に住むような感覚を生み出すためになされたことなのです。

住宅のプロジェクトをランドスケープのプロジェクトへと変えるためにどういった策略をとられていますか?

それは私たちの願望であることが多いですね。私たちの楽しみでもある実務的な部分についてお話ししますね。

建築とランドスケープは異なるものですし、分けて考えるべきだと思います。一方で、建築へのチャンスを、依頼もされていない庭園のデザインへと拡大していくといったこのゲームはとても楽しいものです。一般的に建築家は計画段階で、乾式か湿式かを区分していきますよね。後者はコンクリートの世界のことで、散らかった粉末を水と混ぜ合わせて構造物に流し込んでいきます。前者はソリッドな世界のことで、精密にカットされた素材や細い木材、ネジや仕上げなどのことです。

私は、主に身振りや表現としての湿式に興味があるのです。構造体が空間を定義するのです。

乾式にはそれほど興味がありません。乾式を把握して洗練させていくには、綿密な計画が必要です。それに様々な種類の的確な職人芸や、高価な材料なども必要です。それに最も重要なことは、それに多くの時間がとられてしまうことです。

私は、キャリアのかなり早い段階から、乾式の仕事を省略することでランドスケープなどのもっと興味深いトピックを議論のテーブルに持ち込む時間を確保できるだろうと考えるようになりました。「乾式」へのエネルギーと予算をランドスケープや庭のディテールに還元できるような建物を描くことができれば、単純にデザインの幅が広げられると思うのです。つまり、建築とランドスケープは同じではありませんが、良いランドスケープは過度に洗練された仕上げよりも、いい意味で建築を補完することができるのです。インテリアデザインに対する先入観を捨てて、庭に取り組むようクライアントを説得してみてはどうでしょうか?私たちは率直にクライアントに伝えていますよ。平凡な内装材に使うような資源があれば、とても立派な庭ができますよ、と。

私たちにとって庭は、普段目にできないような空想的な何かを作り出す可能性を与えてくれるものなのです。庭は超現実的なもので、合理的な構造物を補完するには最高の存在なのです。家の中に庭を入れるという話ではないですよ。自然と人工という話でもありません。それは生きたファンタジーなのです。庭は芸術なのです。

庭を造るにあたって、インスピレーションを受けるものは何ですか?

私は公共のプロジェクトから始めていますから、たぶんナイーブすぎるのですが、個人の庭というものは存在しないといった考えをもっているのです。

バレンハウスのような個人邸のためにデザインしたランドスケープも、より大きな場においてその考えが広まっていくと思いたいのです。ひたすらに、その土地に自生する植物だけを使うといった愚かで一般的な考え方を覆すことができますし、区画の区分を気にせずに動植物を受け入れ歓迎することができるのです。

この地域では一般的に行われていることなのですが、贅沢とは、大きな家を建てることではないのだと、他の人にも示すこともできるのです。このプロジェクトでは、小さな構造物だけではなく森林の空き地全体が家であると私たちは捉えているのです。

もうひとつは、植物そのものに関するアイデアです。熱帯地方では、植物を個々に評価するのではなくグループとして評価する傾向があるのです。 ロベルト・ブール・マルクスの作品を見てみると、彼は植物で地形を作り上げるかのようにしているのです。北の地域では季節がありますし、冬には生命のサイクルが途切れて、冬眠に入り、春になるとまた始まって植物が花を咲かせます。とても幻想的な瞬間です。北の人は、冬の間も生き続ける植物を大切に愛でているように思います。北欧のそういうところはとても好きですね。一年のある時期には、個々の植物を室内に入れて保護する必要がでてきます。外では生きられないからですね。こういった行為は植物に新たな意味を与えてくれるものです。

熱帯地方ではそのようなことはありません。むさ苦しくて退屈にも感じられます。熱帯地方の美しさはわかるのですが、無限の生命力が単調さにつながってしまうのです。物事が変化しないのです。ただ、どんどん成長して手に追えなくなっていく。生命のサイクルが途切れないためには、特定の植物が煌めくような空間を作る必要があるのです。南米の屋外庭園を設計していると、個々の植物を見分ける重要性に面白みを感じます。見分けていくためにはレイヤーを構築して、色の濃い緑を背景にする必要があるのです。その前面には例えば、ランの花をちょっとした色味のポイントとして置いたりするのです。

最近では、似た植物を扱うことにも興味があります。例えば、熱帯地方の植物に魅了されていて、それをオスロの庭にも植えたいとします。死なない植物で熱帯地方のものに似たものを探すのです。こういった方法で、異国情緒を喚起するような構成が作り出せるのです。

庭造りで難しいのは、クライアントも含めてですが、土着の植物を使うように言ってくる人に出会うことなのです。それは、私にとってチャンスの損失を意味します。自然には起きないことが起き、物事がミックスされる風景が最も美しいものだと私は思っていますから。

私たちはこのアイデアをバレンハウスで探求していきました。この住宅は、海抜2100メートルの高さにあるのですが、私たちはパラモ高原のような風景にしたいと思ったのです。そこは、標高3000メートル付近より上の生態系が保護されている場所です。本当のパラモ高原では家を建てたり個人の庭をもったりすることは許されません。それに、その生態系の中の植物をもって降りることもできません。生き延びることができないからです。ランドスケープアーキテクチャーでは、建築におけるプロポーションやマテリアルのように美学的なコードを簡単に取り入れることはできません。植物が生きるか死ぬか、なのです。無慈悲なものです。結局、私たちがやったことは、パラモ高原の植物に近い見た目のもので、海抜2100mでも育つものを選ぶことでした。標高のはるか高くにある庭がイリュージョンとして構築されたのです。いくぶんポストモダン的な庭の考え方なのかもしれませんが、本当に不思議な空間が作れるのです。ノイトラがいくつかの住宅で試していたのと同じ考え方なのです。

実際、バレンハウスを写真から特定するのはとても難しいですよね。

パラモ高原は、ある意味典型的なアルプスの風景にとても近いものがあるのです。完成直後は、この家が、ノルウェーかスイスにあるように思う人もいるでしょう。こういった不定性に非常に興味があるのです。コロンビアなのか、ノルウェーなのか、スイスなのかわからないようなね。そのためにはあらゆる状況をモデリングし直すといった包括的戦略が必要でした。

この家は森の空地にあって、そこは何世代も牛が土を踏み固めてきた場所なのです。そこに何かを植えるのはとても難しいことでした。文字通り土を取り除く必要がありました。敷地には外来植物も多く生息していたのです。

単純に庭を作ったとしても蓄牛に使われるような侵攻力の強いオーストラリアの草に飲み込まれてしまうのです。家の周囲の生物質を入れ替えて、外来種の草の残骸を燃やし、私たちがこうあるべきだと思う庭の考えに従って土壌を再構築する必要があったのです。すごく面白いのです。建築的、生物学的なコンテクストを完全に発明することが。それが作られたもので奇妙なものであったとしても、不思議なことに親しみのあるものに見えるのですから。

2022年10月7日

Luis Callejas: It was back in 2014, when Charlotte and I were about to start working together, that we got an invitation from the Los Angeles based curator Mimi Zeiger to stay a week at the VDL house and exhibit our work. It was our first project together, and the time spent at the house became an important step in plotting a new path for our office.

The VDL house was a place where the Neutras received clients, experimented with space and materials, and explored how to design modest quality, and what quality meant in the moment when ideas about luxury where changing. It was simultaneously a domestic space, a workshop, and an office - a condition and lifestyle I find very inspiring.

IT’S NOT ONLY A HOUSE, BUT ALSO A PROTOTYPE FOR FUTURE HOUSES.

You could say the VDL is a house about what’s coming next. Neutra called it a research house. I had seen this experimental approach in a few houses before, but typically experimental houses that evolve step by step have a sort of bricolage character which I am not particularly interested in.

It is important that a project has a clear intention. Although having said that, I do appreciate a dose of that ‘work-in-progress’ atmosphere, of something being tested, unfinishedness, that exploratory spirit which gives rise to a sense of openness, freedom. I guess in the right measure it looks effortless.

In our recent projects we have tried to do something similar, which is to use fragments of a house, sometimes details, as tests for future projects. To give you an example, we recently completed a house consisting of two volumes in a beautiful, sloped forest clearing. We used the same materials, the same formwork, the same details, in two houses of more or less the same surface area. We were interested in how the space feels when the only differences between the volumes is the geometry of the plan and the position of the structure in regard to the surface of the earth. One volume is elongated, another one is a square, one is half sunken, the other is elevated. The first, like a retaining wall, feels more humid in the rainy season, the other feels airier and extroverted. These two experiments are now completed and allowed us and the client to discuss how to continue with future houses in the 80-hectare plot.

The VDL house feels close to our way of making architecture, or at least to something we aspire to. It is very much a house about future commissions. Now that I think about it, the time spent there informed the recent project I just described. I remember that Sara Lorenzen and her husband David were living in the small Neutra’s guest house across the courtyard. Every day we would meet to chat in the garden, or they would invite us for coffee. I really love this idea that two strangers, friends or families can live close enough, separated only by a garden, and out of daily serendipity, have encounters or invite each other to do something together. We ended up doing the same in the houses in El Retiro - a large garden and two separate structures that allow these encounters to occur.