エルヴィン・ビライ: 『聴竹居』を選んでお話することにした理由は二つあります。

一つ目に、この住宅が環境工学的にサスティナビリティの問題にいち早く取り組んでいた住宅であること。もちろん国際的に最も議論されているテーマの一つですよね。

二つ目に、この住宅の一過性に強く惹かれたこと。日本の社会がダイナミックに変化していた時代の証左としての住宅。

その建築は日本と西洋、両方の特徴を備えていました。建築家 - 藤井厚二はメートル法を用いたパイオニアでした。住宅空間の設計に用いられる日本の伝統的な畳システムへの挑戦。それだけで慣習的な日本の構造システムとは全く異なるものになっています。ところがその全体的特徴は地域の感性からダイレクトに影響を受けており、優美な木造の茶室にもみられるような数寄屋的特性を持っています。

藤井厚二が『聴竹居』で融合を試みた西洋的特徴と日本的特徴とはどういったものですか?

20世紀が始まり最初の20年間、日本では国に相応しい様式や素材(木なのかレンガなのか)、さらには日常文化への西洋からの影響をどう取り入れるかが盛んに議論されていました。ヨーロッパからの技術や美学がかつてないほどに日本建築の論壇において存在感を増していったのです。

そういった状況でしたから、日本らしさ、つまり日本建築の特異性や国民性を守りつつ新しい状況に適応させることが、重要なカウンタートピックとなり得たのです。『聴竹居』より以前は、日本の貴族の慣例が規範となっていました。新しい官邸は二棟のペアで計画されたのです。日本の木造の伝統的な住宅。そしてそれに隣接する西洋のレンガ造りの住宅。

西洋の建物は、テーブルに椅子を並べて座るといったエキゾチックな活動のためのおしゃれな東屋として使われていました。異文化の新奇性を認めつつも同時に、日常生活における国民性の再認識や進化を怠っていたわけです。ですから、藤井厚二が二つの「様式」を一つの住宅に融合したのは驚きでしたし革新的でした。

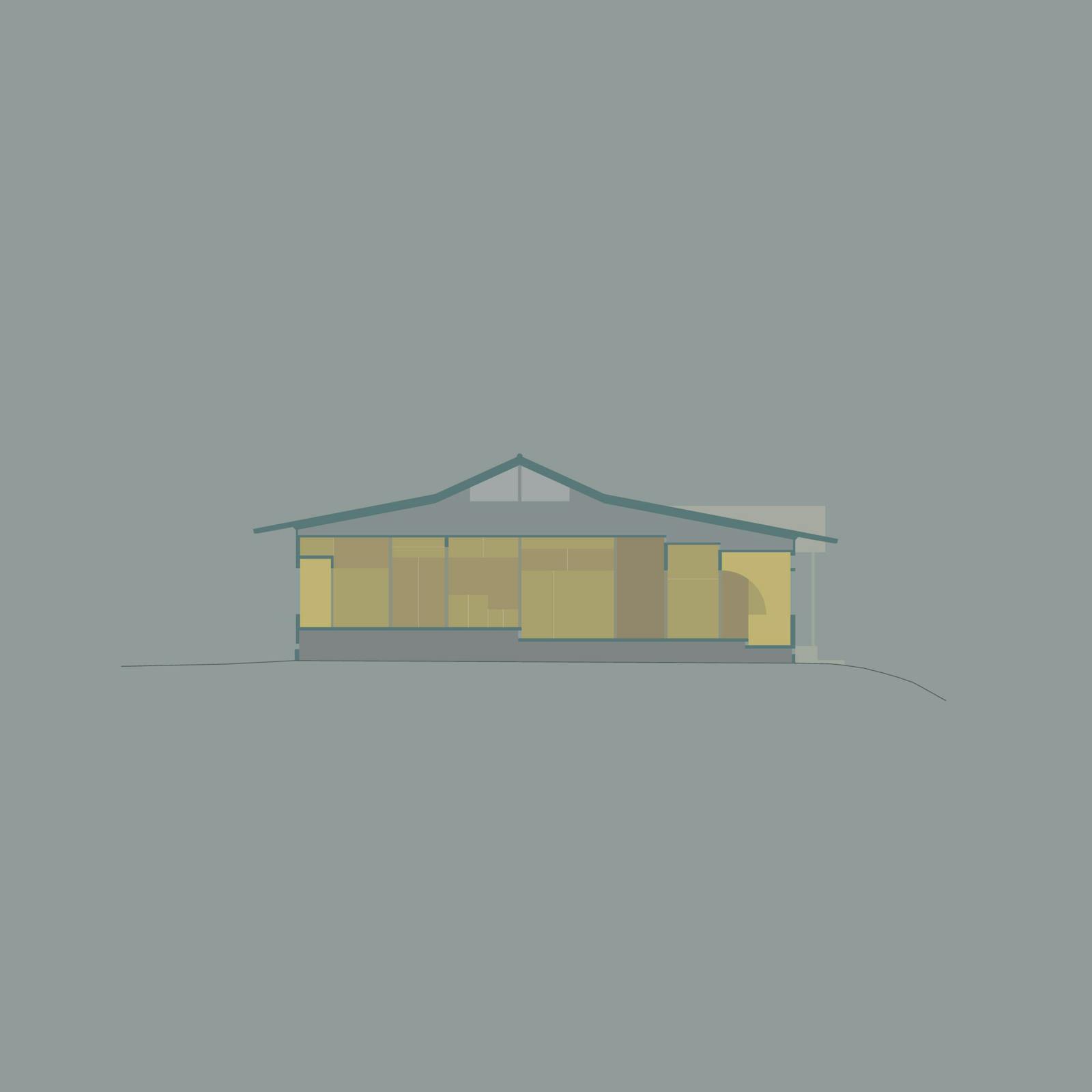

その意図は、建物の外観からもすぐにわかります - コーナーを回る窓はモダニズムの特徴として代表的なものですね。内部に入ると電気照明が目に入ってきますが、この照明はまさにフランク・ロイド・ライトを意識したものです。彼は当時、東京で帝国ホテルを建設していました。さらに注目すべきは、ダイニングルームとリビングルームとの間に設けられた曲線の開口部です - どこかから引用されたもので、日本のものではありません。

それに、それぞれの部屋は特定の機能が与えられていて、内部の家具や建物内での部屋の位置関係が考慮されています。畳を敷くのではなく西洋的な測定法によって空間が作られているので規則的な感じがあるのですが、空間内の人や活動という次元にとっては抽象的になるのです。

最近ヘルマン・ムテジウスの『The English House』(1904年)に目を通していたのですが、『聴竹居』の平面計画はムテジウスの文章にインスピレーションを受けたのかもしれないと気づきました。私の知る限りですが、この本は1920年代の日本の建築家の間にも広まっていたものなのです。

住まいの質について分析をした周密な著作なのですが、そこで著者は、住宅内の特徴的な空間をそれぞれ独立した存在として記述しているのです。例えば藤井厚二は、寝室を住宅の中では離れた場所に設定していますよね - かなりアヴァンギャルドで「ヨーロッパ的」な判断です。

個々の部屋はどうやって決められているのでしょうか?好みによって機能を変えることはできないものなのでしょうか?

たいてい日本の住宅は、寝室とダイニングルームに大きな違いがありません。リビングルームがダイニングルームや寝室になったりもします。『聴竹居』においても理論的にはリビングルームとダイニングルームを取り替えることはできます。どちらもメインスペースにありますから。私は部屋の機能というものは、それがどこにあるのかによって決まるものだと思うのです。これは非常にロース的な家庭空間の考え方ですね。パブリックエリアとプライベートエリアは、開閉の度合いやアクセスのしやすさといった特徴によって区別されるものです。『聴竹居』が日本的な正当性から特出しているのは、こういった特徴があるからでしょう。

典型的な日本的要素で残っているものはありますか?

例えば薄暗い照明への好み。谷崎潤一郎の『陰影礼讃』(1977年)からもお分かりだと思いますが、日本では伝統的に空間の明暗を魅力的なものとして捉えます。『聴竹居』は近代的ドグマが推し進めるような光に満たされた白さではなく、むしろ暗さのある箱なのです。藤井厚二は伝統的な町屋のインテリアを想起させる素材を用いていますし、境界の作り方もまた、客を迎え入れる日本の儀式に深く根ざしているものだと思います。

客を迎え入れる儀式とは、どういうことですか?

日本の空間にはいつも階層や順序があって、どういった活動ができるかとか、どれくらい近づいていいのか、といったことがコントロールされています。ですから、さまざまな活動を許容する部屋があることはいいことなのです。客を招いた時に、どこから入るべきか説明を要するような境界を作る必要もありません。『聴竹居』の中心にある空間は、客を招くためのフォーマルな空間でもありますが、隣の部屋で活動が行われている時には回遊動線としても使われます。

このリビングルームが家の中での共同生活への関わり方にグラデーションを作ってくれるのです。そのおかげで自分自身の自律性や居場所としてのプライバシーを保ちながらも、それぞれの部屋では何が起こっているのかを感じることが可能なのです。許可を得るまでは、身体的にも聴覚的にも邪魔をしてはいけない。日本においての強力な社会的規範の特徴ですね。

西洋的な理解の仕方では、茶室の使われ方があまり明快に理解できていないかもしれません。

どう使うものなのか教えていただけますか?

今お話している住宅の場合、茶室自体は家の中にはありません。家の背後に小さなパビリオンがあって、そこに茶室としての十分な要素が備えられています - 茶室へといたる小道もあります。その小道は中に入る前に体を清める装置となるのです。

入り口は小さく、中には畳や床の間、客のための場所、それに茶を立てる場所が用意されています。座る場所は、客によって変化するものです。茶会は客を歓迎する方法であり、そこでは日常生活から平静と距離をとり、恒常的な自然の美しさに対峙するのです。

日本の畳システムによって作られた空間は、実際よりも大きく感じたり小さく感じたりするものなのでしょうか?

簡潔に答えを述べることは難しいのですが、この住宅には、西洋的な寸法と東洋的な雰囲気の組み合わせによる効果が見られます。『聴竹居』が大きく、天井が高く見えるのはおそらくメートル法によるためでしょう。例えば、日本の空間はたいてい天井がかなり低いのですが、フランク・ロイド・ライトもそのことを理解していて上手く設計に取り入れていましたね。日本やアメリカで建てられた彼の住宅を見にいくと、天井が低く軒も随分と長いことにすぐに気づきます。内部の光はとても控えめで、とりわけ眩しさは感じません。例えばですが、ミースの作品とは全然違うものですね。ファンズワース邸では光が床面いっぱいに差し込みますが、悪く言えば眩しいのです。

ある数寄屋大工が教えてくれたことを思い出します。要は目線の高さが非常に重要なのだと。たいてい茶室は小さな空間なので、立ったまま入ると窮屈で閉じ込められたように感じるのですが、膝をついて座ると目線が低くなり部屋が急に高く感じられます。目線の劇的な変化のない西洋の住宅では、こういった感覚を味わうことはありません。椅子に座った時に目線が一番低くなるくらいですからね。

『聴竹居』において内外の連続性については、どのようなことが考えられているのでしょうか?

内外の関係性のことを考えると普通は窓に着目しますよね。どう開けるかとか、どれくらい大きくするかとか、どれくらい透明なのかとか。本当は外部の構成によって決まるものだと私は考えています。

『聴竹居』の場合、まわりの植栽を気にして見てください。室内から見たときに奥行き感を作る非常に重要な要素となるのです。

庭自体の空間は比較的小さなものかもしれませんが、植物の選び方や配置の順序によって不思議にも奥行き感が生まれているのです。イリュージョンです。ヨーロッパにおけるバロック期の発明にも引けを取らない、内外の特別な関係を創出するデザインです。

日本文化における庭の構成では、時間と空間が強く意識されています。季節の変化による効果を想像しながら植物を選定し、広がりや囲われの感覚を作り出せるのです。私の持っている『聴竹居』の本には、春夏秋冬で異なる景色が映し出されています。冬に雪が降るといつもは暗がりにあるものが目に見えてきますね。雪が黒い枝に積もるときとか。秋にはあらゆるものが赤と黄色の色合いに染まり、夏と春には緑の色合いに染まる。こういった状況が広がりや囲われの感覚にさまざまな影響を与えるのです。

『聴竹居』が1920年代の建築産業に与えた影響はどういったものだったのでしょうか?

色々な点で大きな影響力があったと思います。日本で非常に普及している規格化住宅の雛形を作ったのです。組み立て方や機能や空間の割り振り方、それに寸法や動線などを見てみると、それらが藤井厚二のこの住宅に由来していることがわかります。

藤井厚二の直後から多くの建築家が、伝統的要素と西洋的要素を一つの住宅の中に融合するという課題に取り組むようになりました。例えば、堀口捨己はオランダでデ・ステイルを学んだ後、1933年に『岡田邸』を建てました。モダニズムの白い箱に伝統的な日本の屋根が乗っかっている建物です。

もう一人の建築家 - 前川國男はル・コルビュジエのもとで働き、その思想を日本へ持ち帰ってきた建築家です。それにアントニン・レーモンドのおかげでフランク・ロイド・ライトの影響が日本では根強いですね。彼はアメリカでライトのもとで働いた後、日本にやってきた建築家です。

1920年代の建築家たちは、鉄筋コンクリートといった新しい素材や家具にみられる新しい生活様式を取り入れ、日本の伝統と融合させる実験を繰り返していました。1920年は極めて重要な年です。東京大学の学生たちが、国の保守性や西洋の様式を優先する態度からの解放宣言を掲げて展覧会の開催を発案したのです。彼らは日本のアイデンティティを貶めることなく、自由な創作や彼らの生きる時代の表現を求めたのです。『聴竹居』は1928年に竣工しました。それは学生たちの宣言 - 常に変化と進化を続ける近代世界の中でいかにして日本人の精神を保つのか、という思いの投影されたものでした。

私の東京大学での博士論文は、明治時代から伊東豊雄に至るまでの学生の卒業制作をドキュメントとしてアーカイブ化したものでした。それらを通して、素材や建設技術、社会的習慣の変遷を追うことができました。そして何よりこうした変化をもたらす元となった認知や影響を理解することができました。

この住宅における環境へのこだわりはどこに表れていますか?

藤井厚二博士は、京都大学の環境システム学の教授でした。『聴竹居』は空気の流れをコントロールすることでいかに健康的な住空間を作れるかという実験だったのです。

個々の空間の機能が明確化されているのもそのためです。素材の使い方や地形との関係も示唆的です。『Cho-chiku-kyo』は漢字で書くと『聴竹居』ですから、聴く、竹、住まい、という意味があるのです。

敷地の傾斜を見ていただくと、空気がどこを流れ、その流れが冬と夏とではどう変化するのかが想像できると思います。それに応じて適切に家を換気できるのです。日本の古い家屋を見るとかなり閉鎖的であることがわかると思います。特に冬場は湿気と風通しの悪さで、むっとして息の詰まるほどです。京都の古い町屋は夏をもって旨とすべし、と言われているように全てをオープンにすれば問題なく換気することができるのですが、冬にはそう簡単にいきません。それに京都は山に囲まれているので、家の中の空気は熱がこもってしまい健康なものとは言えません。藤井厚二のイノベーションはこうした問題の解決を目指したものでした。

サスティナビリティのためのモデルとして『聴竹居』は何を提示しているのでしょうか?

今では誰もがテクノロジーに夢中で、それ自体が間違っているとは思いません。ですが、まずは人間としての私たちを理解し環境に対してどう応えていくべきかを考えるべきだと思います。私たちは常々、消費ゼロ、廃棄ゼロ、排出ゼロ、と言っているわけですが、目標を設定して達成への道のりを定めることは難しくないはずです。

大事なのは、こうした統計や戦略よりも私たちが人間であることを忘れないことだと思います。つまり建築家としての私たちが、文化と密接な関係を持たなくてはいけない。サスティナビリティは、私たち自身の振る舞いを認識することによってのみ可能なものなのでしょう。

藤井厚二の孫(小西信一)の回想録を読むと、彼が『聴竹居』の台所にいたときの記憶が描かれています。そこで彼は、建築に導かれるようにして行っていたある振る舞い、つまり、生ゴミを収集し庭の肥料にすることがいかに効率的であったかを思い出すのです。なんてことはない方法で、建築は異なる視点から日常生活への実践を示唆してくれるものです。

日本では、庭や小道を歩いていると道の真ん中に縄でくくられた石が置かれているのを見ることがあります。これ以上先に進んではいけないというサインです。日本人の振る舞いに特有なこうした小さなサインはたくさんありますし、私たちの文化に刻み込まれているものなのです。こうしたシンプルで穏やかなサインは、環境にとって良い行いを私たちに導いてくれるはずなのです。

数字や統計の話ばかりするよりも、こうしたソフト面での対策の方が可能性があるのではないでしょうか。『聴竹居』が有名になったのは、技術的に高度な解決策を提示したことに加えて、藤井厚二がそのことを文章で強調していたからです。ですが、それよりもサスティナブルという観点で重要な特質がこの住宅にはあるのだと思います。要するに、周辺環境の質、伝統的な振る舞いへの敬意、そして抑制された好奇心に育まれた控えめなイノベーション、ということでしょうか。

『聴竹居』は広い視野をもった事例と言えるでしょう。それ自体が興味深い住宅でありながら、環境との関係を保持している。つまり丹下健三と同じように、建築を扱うことは、ただのオブジェクトとしてではなく、あらゆるスケールを横断し都市との関わりを持つことなのだ、ということに藤井厚二も意識的であったのです。

今日の議題は、様式からサスティナビリティへと変わっていったということですが、様式の問題は解決されたのでしょうか?

人々はオーセンティックなものを求めているようです。気候非常事態によって、抽象的な問題を議論するよりも、私たち自身を見つめ直し、私たちの立ち位置を模索する必要が出てきたのです。私たちの周りには複雑なことが起こっていますし、その中で形の議論に対する比重が下降傾向にあるのはお分かりでしょう。もちろん議題の一つとして残るとは思いますが、より広域な環境にとって、それがどれほど貢献的なものなのかはわかりませんね。

2021年11月06日

Erwin Viray: I have chosen to speak about Chochikukyo for two reasons.

Firstly, it seems to be one of the earliest houses to address, through environmental engineering, the issue of sustainability, which, as we are all aware of, is currently one of the most discussed international topics.

Secondly, I was always very attracted by its transitory character. As a house it's a testimony to a period of dynamic change within Japanese society. Its architecture has both Japanese and Western features. The architect - Koji Fujii was a pioneer in the use of the metric measurement system, which challenged the traditional Japanese Tatami language of spatial planning in residential buildings. Only because of this, the house already feels very different from typical Japanese structures. Nevertheless, its overall character stems directly from the local sensibility and has a lot in common with Sukiya style (1574-1867) architecture - which was partly present in elegant wooden tea ceremony pavilions.

WHAT WERE THE WESTERN AND JAPANESE FEATURES THAT KOJI FUJII MIXED IN CHOCHIKUKYO?

The first two decades of the 20th century in Japan were a period of vivid discussion on the appropriate style, materiality (wood or bricks) and inclusion of western influences in everyday culture. At the time, European techniques and aesthetics were becoming ever more present in the Japanese architectural debate.

As such, protecting Japan-ness, i.e., the specificity and national character of Japanese architecture, while adapting it to the new conditions, became an important counter topic. Before Chochikukyo was built, the example was set by Japanese nobility, who, when erecting new official palaces, built them in pairs; a Japanese wooden, traditional house and a Western brick version next to it.

The Western building served as a sort of fashionable pavilion for exotic activities like sitting at a table with chairs etc., an acknowledgement of the novel developments of another culture but at the same time a failure to re-understand or evolve the national way of life. It was therefore surprising, and innovative, that Koji Fujii combined these two „styles” in one house.

This intention is immediately visible from the exterior of the building - windows wrap around the corners, a well-known modernistic feature, and upon entering, you see electric lighting, directly inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, who was building the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo at that time. Also noticeable, is the curved wall opening between the dining room and the living room - a quotation, and something that had not been done in Japan before.

Moreover, the rooms have a specific function, related to the furniture they contain and their location in the house. Spaces were not defined by the laying of mats, but by western measurements that are at once precise but then also abstract to the dimensions of people and cultural movements in space.

I recently skimmed through the book The English House (1904) by Herman Muthesius and realised that the layout of Chochikukyo could have been inspired by Muthesius’ writing. As far as I know the publication circulated among architects in Japan during the 20’s.

It’s a meticulous work, analysing the qualities of dwellings in which the author describes each specific space of a house as a separate entity. For example, in Chochikukyo the bedrooms are clearly defined in a separate part of the house – which would have been a very avant-guard or ‘European’ decision.

HOW ARE THE INDIVIDUAL ROOMS DEFINED? COULDN’T YOU CHANGE THE FUNCTIONS ACCORDING TO YOUR PREFERENCES?

Usually in Japanese houses, bedrooms and the dining room are not that much different. A living room can be a dining room, can be a bedroom etc. In Chochikukyo you could theoretically swop the living with the dining room, they are both part of one main space, however, as far as I am concerned, the functions are meant to be where they are. It was very much a Loos’ian way of thinking about domestic space. The public and the private areas are distinguished in their character, grade of opening and access. I think, it was a feature that pushed Chochikukyo even further from the Japanese orthodoxy.

WHAT TYPICAL JAPANESE ELEMENTS REMAIN IN THE BUILDING?

For instance, the preference to have rather dim light. As you might know from the book In Praise of Shadows (1977) by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, in the Japanese context, the spaces between lightness and darkness are traditionally perceived as attractive. Chochikukyo is not a white box soaked with light, as the modern dogma might have prompted, it is instead darker, with Koji Fujii using materials that recalled the interiors of traditional Machiyas. The way of using the thresholds between spaces is also deeply rooted in the ceremonial way of receiving guests in Japan.

WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY CEREMONIAL WAY OF RECEIVING GUESTS?

In Japan, there is always a hierarchy or sequence which determines how activities and levels of intimacy are controlled. It’s better to make a room suitable for a diverse spectrum of activities and as such, you would avoid creating thresholds that require guests to receive invitations or directions to enter. The central space in Chochikukyo is a formal space for receiving guests, but it also allows circulation if the adjacent spaces are occupied by other activities.

This so-called living room enables the gradation of involvement of spaces in the common life of the house. Thanks to it, you can be aware of what happens in each room, whilst maintaining your autonomy and the privacy of the place you are in. The compartmentalisation of the activities and the spaces enables a subtle mediation of in-between situations. You never intrude either physically or acoustically into a space before being allowed to do so. It’s a very strong characteristic of Japanese social norms.

IN A WESTERN CONTEXT, IT IS PROBABLY NOT VERY CLEAR HOW A TEA HOUSE IS USED. HOW DOES IT WORK?

In the case of the house we discuss, the teahouse is not in the house itself. There is a smaller pavilion behind the house. It has the proper components of a teahouse - there is a pathway to reach it and the necessary devices to purify yourself before entering. The entrance is small. Inside you see Tatami mats, the tokonoma, the place of honour, and the place where the host prepares the tea. The seating is arranged based on who is the guest. A tea ceremony is an elaborate way of celebrating the presence of guests, peacefully distant from everyday activities, and relative to the ever-present beauty of nature.

DOES THE SPACE BUILT ACCORDING TO THE JAPANESE TATAMI SYSTEM SEEM BIGGER, OR SMALLER THAN IT REALLY IS?

It is difficult to answer directly, the effect of the house is result of a combination of western measurements and eastern atmospheric conditions. Chochikukyo seems to be bigger and higher, probably because of the metric system it follows. For instance, ceiling height, in Japanese space is usually quite low, and is a character that Frank Lloyd Wright equally captured and adopted successfully in some of his buildings. If you go to visit the houses he built in Japan or to some of his houses in the US, you immediately see that the ceiling is low, and the eaves are longer than you would expect. The quality of light inside becomes very subdued, the environment is never particularly bright. It is very different from the works by Mies for instance. In the Farnsworth house light penetrates the plan fully and at worst, you experience even glare.

I remember a lesson that one Sukiya carpenter gave me. Namely, that the level of the eye is very important. The Tea room for example, is usually a small space and when you enter, standing, it feels very confined, very claustrophobic. But when you kneel and sit down your eye level is very low, and the room suddenly feels much higher. You rarely have this feeling in Western houses which are not usually designed around radical changes in viewpoint; the lowest level you reach is when you sit down on a chair.

HOW DOES CHOCHIKUKYO DEAL WITH THE CONTINUITY BETWEEN INSIDE AND OUTSIDE?

Usually when we speak about the relationship between inside and outside in a house we tend to concentrate on windows, the way they open, how big, or transparent they are and so on. However, as far as I am concerned, the right effect is often very much bound to the composition of what is outside.

In case of Chochikukyo one should look at how the vegetation is coordinated around the house. Its effect is extremely important on how a sense of depth is created when looking from inside.

The space of the garden might be relatively small, but because of the plants, the species that were selected and the way they have been placed behind each other, a magical depth is created. An illusion. Comparable to the experiments of the Baroque period in Europe, the design produces a special relationship between the inside and outside.

In Japanese culture, the composition of the garden is strongly orientated to time and space. You create a widening or an enclosure and within it; you choose the plants carefully to perform certain effects in different seasons. I have a book on Chochikukyo, that shows the differences of views you have in summer, spring, autumn and winter. You can see that in the winter when the snow falls, what normally is dark becomes luminous, you have the snow on the black branches. In autumn, everything is in different shades of red and yellow. In summer and spring, you have instead diverse shades of green. Each of these situations has a different impact on your feeling of continuity or enclosure.

WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF CHOCHIKUKYO ON THE ARCHITECTURAL PRODUCTION IN THE 1920’S?

It became very influential in many ways. It created a template for prefabricated modular houses, that are today still very popular in Japan. When you look at how they are assembled and how they define functions and spaces, measurements and circulation, a lot comes from this house by Koji Fujii.

Shortly after Koji Fujii, many architects started to work on the task of melding both traditional and western elements in to one house.

For instance, Sutemi Horiguchi went to Holland and studied De Stijl before going on to build the Okada House in 1933, which was a combination of a modernist white box with the windows and roof taken from a traditional Minka.

Another architect - Kunio Maekawa, worked with Le Corbusier and brought his ideas home. You could find a very strong influence of Frank Lloyd Wright brought over to Japan by Antonin Raymond. He went to work with FLW in the USA and eventually ended up in Japan.

During the 1920s these architects were experimenting a lot, introducing new materials like reinforced concrete, new concepts of living, like furniture, and mixing them with Japanese traditions. 1920 was a pivotal year. A group of students from the University of Tokyo decided to make an exhibition declaring freedom from the conservatism, but also from dominance of Western styles of architecture. They intended to create something free and expressive of the age they lived in, whilst not discrediting Japanese identity. Chochikukyo was built in 1928. It reflected the student’s declaration - a reflection of how to keep the Japanese spirit in an ever changing and evolving modern world.

For my PhD dissertation at the University of Tokyo, I documented and created an archive of student graduation works from Meiji period all the way up to Toyo Ito. Through this I could observe the transformation in materials, construction techniques, social customs and importantly, the perceptions and the influences that gave rise to these changes.

HOW ARE ENVIRONMENTAL PREOCCUPATIONS EXPRESSED IN THE HOUSE?

Dr Koji Fujii was a professor of environmental systems at the University in Kyoto. Chochikukyo became an experiment centered on how you can create healthy domestic spaces, through the management of airflow.

This preoccupation clearly defined the function of individual spaces. It also had implications on the materials used, and the relationship of the house to the terrain. Chochikukyo, written in Chinese characters 聴竹居means: “listen, bamboo, dwelling.”

There’s a certain slope, looking at it, you can imagine where the air would flow and how this would change during the winter and summer, ventilating the house accordingly and properly. If you look at some of older houses in Japan, they are quite closed, and can be stuffy due to humidity and lack of airflow, especially in winter. The old Machiyas in Kyoto are designed for summer, as people say, because you can open everything and ventilate perfectly, in the winter it was not so easy. Moreover, Kyoto, surrounded by mountains, retains a lot of heat, and the air quality in the houses was never as healthy as one would have wished it to be. Koji Fujii’s innovations were aimed at addressing these issues.

WHAT MODEL OF SUSTAINABILITY DOES CHOCHIKUKYO PROPOSE?

Now everybody is fascinated with technology, and it’s not wrong per se, I just think that first we should understand ourselves, as human beings, and the ways in which we react to the environment around us. We speak all the time about zero consumption, zero waste, zero emission. It’s clear we can set targets and determine ways of achieving them.

However, what I think is important, above all these calculations and strategies, is not to forget the human being. That means, as architects, we need to operate in tight connection with culture. Sustainability is only possible if we acknowledge it in our own behavior.

Reading through the recollections of Koji Fujii’s grandchild (Konishi Shinichi) you encounter memories of being in the kitchen at Chochikukyo, where he was guided by architecture to behave in a certain way.

He would remember how it was very efficient for them to collect the organic waste, and later use it to fertilise the garden. In a very subtle way, architecture can somehow guide you through everyday life and make you practice things differently or perhaps in a better light.

Often in Japan, when you’re in a garden or on a pathway you will find, placed carefully in the middle, a stone with a rope on it. Usually, this sign means that you are not to go further. There are many little signals like this that are inherent in Japanese behaviour, engrained in our culture. In my mind, simple calm signs such as these, could be useful in guiding people to do certain things that are better for the environment.

I see this kind of soft strategy potentially more successful than talking only about numbers and statistics. Chochikukyo became famous because of its technically advanced solutions and the emphasis Koji Fuji put on them through his writing. However, I think there are more important qualities within the house, that make it sustainable. Namely, the qualities of the environment around, the respect towards patterns of traditional behaviour, discreet innovations that nourished curiosity without overwhelming it.

Chochikukyo is an example of a broader vision. Not only is the house interesting itself, but it has a relationship to its environment. Similarly, to Kenzo Tange, Koji Fuji was aware that when you deal with architecture, it’s not just about an object. It crosses all scales and deals with the city.

WE HAVE PASSED THROUGH AN EPOCH OF DISCUSSION ABOUT STYLE AND ARRIVED AT THE POINT OF SUSTAINABILITY. ARE WE DONE WITH STYLISTIC ISSUES?

People seem to be looking for authenticity. Because of the climate emergency there is a need to look at ourselves and investigate where we’re standing, rather than discussing about abstract issues. There are complex things happening around us. And we can observe that the topic of form slides down the hierarchy of importance. It will of course remain part of the discussion, but it will be questioned to what extent it supports the quality of the much wider environment.

06.11.2021

埃尔文-维雷 我选择谈论听竹居有两个原因。

首先,它似乎是最早通过环境工程解决可持续性问题的住宅之一,正如我们所知,可持续发展是目前讨论最多的国际性话题之一。

其次,我一直被它的过渡性特质所吸引。作为一栋住宅,它见证了日本社会的一个动态变化时期。

它的建筑同时具有日本和西方的特点。建筑师藤井厚二是使用公制测量系统的先驱,这对日本传统的住宅建筑空间规划上使用的榻榻米度量构成了挑战。仅仅因为这一点,已经能感受到这所住宅与典型的日本结构有着很大的不同。然而,它的整体特征直接源于当地的感觉,与数寄屋风格(1574-1867)的建筑有很多共同之处——这部分的呈现于优雅的木制茶室中。

藤井厚二在听竹居中混合了哪些西方和日本的特点?

20世纪头20年的日本,活跃着关于合适的风格、材料(木头或砖)和在日常文化中纳入西方影响的讨论。当时,欧洲的技术和美学越来越多地出现在日本的建筑讨论中。

因此,保护日本性,即日本建筑的特殊性和民族性,同时使其适应新的条件,成为一个重要的对立话题。在听竹居建成之前,日本贵族树立了榜样,他们在建造新的官方宫殿时,都是成对建造的;一座日本的木制传统住宅和旁边的西方砖制住宅。

西方的建筑作为一种用于异国情调活动的时尚的场馆,如坐在有椅子的桌子前等,这是对另一种文化新发展的承认,但同时也是对民族生活方式的重新理解或发展的失败。因此,藤井厚二将这两种 "风格 "结合在一栋住宅中是令人惊讶的,也是创新的。

这种意图从建筑的外部就可以看出来——窗户环绕着角落,这是一个著名的现代主义特征,一进门就可以看到电灯,直接受到弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的启发,他当时正在东京建造帝国酒店。同样值得注意的是,餐厅和起居室之间的弧形墙体开口——这是一种引用,也是以前在日本没有做过的事情。

此外,房间的规划具有非常具体的功能。卧室在住宅的一个独立部分(删除并移至下一段)。房间有特定的功能,与其中的家具和房间在住宅中的位置有关。空间不是由铺设榻榻米来定义的,而是由西方的测量方式,这些测量方式一方面精确,一方面对于人和文化活动在空间中的尺度是抽象的。

我最近浏览了赫尔曼-穆特修斯(Herman Muthesius)的《英国人的住宅》(1904)一书,意识到听竹居的布局可能是受到穆特修斯的启发。据我所知,该出版物在20年代的日本建筑师中流传。

这是一部细致的作品,分析了住宅的品质,其中作者将住宅的每个具体空间都描述为一个独立的实体。例如,藤井厚二的卧室被明确定义为住宅的一个独立部分——这本来是一个非常前卫或 "欧洲 "的决定。

每个房间是如何定义的?你不能根据自己的喜好来改变功能吗?

通常在日本的住宅中,卧室和餐厅没有太大的区别。客厅可以是餐厅,也可以是卧室等等。在听竹居,理论上你可以把客厅和餐厅调换一下,它们都是一个主要空间的一部分,然而,就我而言,这些功能就应该在那里。这在很大程度上是路斯对家庭空间的一种思考方式。公共区域和私人区域在其特征、开放程度和可达性方面是有区别的。我认为,这是一个将听竹居进一步推离日本正统观念的特征。

建筑中保留了哪些典型的日本元素?

例如,对相当幽暗的光线的偏好。正如你可能从谷崎润一郎的《阴翳礼赞》(1977)一书中知道的,在日本语境中,明暗之间的空间传统上被认为是有吸引力的。听竹居并不是像现代主义教条所提示的那样,是一个浸泡在光线中的白色盒子,相反,它更黑暗,藤井厚二使用的材料让人想起传统町屋的内饰。在空间之间的使用门槛的方式也深深地扎根于日本的待客礼仪。

你说的待客礼仪是什么意思?

在日本,总是有一个层级或顺序,去决定如何控制活动和亲密关系的等级。最好是使房间适合多样化的活动,因此,你会避免创造那种需要客人受到邀请或者指示才能进入的门槛。听竹居的中央空间是一个接待客人的正式空间,但如果相邻的空间被其他活动占据,它也允许被作为交通空间使用。

这个所谓的起居室使得不同空间在住宅共同生活中的参与程度有所分级。由于它的存在,你可以意识到每个房间里发生的事情,同时保持你的自主性和所在之处的隐私。活动和空间的分隔使得一种微妙的介于两者之间的情况成为可能。在被允许之前,你永远不会从身体上或声音上闯入一个空间。这是日本社会规范的一个非常强烈的特点。

在西方背景下,可能不太清楚茶室是怎么使用的。它是如何运作的呢?

以我们所讨论的这所住宅为例,茶室不位于住宅主体之中。住宅后面有一个较小的别馆。它有茶室的适当组成部分——有一条通往茶室的小径,以及进入前净化自己的必要装置。入口很小。在里面你可以看到榻榻米、床之间,荣誉的地方,以及主人准备茶的地方。座位是根据谁是客人来安排的。茶道是庆祝客人光临的一种精心设计的方式,平和地远离日常活动,并与自然界的永恒之美相对。

根据日本榻榻米系统建造的空间看起来比实际情况大,还是小?

很难直接回答,住宅的效果是西方的测量方式和东方的氛围相结合的结果。听竹居似乎更大更高,可能是因为它遵循的公制系统。例如,天花板的高度,在日本的空间通常是相当低的,这也是弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特在他的一些建筑中同样捕捉并成功采用的特征。如果你去参观他在日本建造的住宅或他在美国的一些住宅,你会立即看到天花板很低,而且屋檐比你想象的要长。内部的光线品质变得非常柔和,环境从来不是特别明亮。这与密斯等人的作品非常不同。在范斯沃斯宅中,光线完全穿透了整层,在最坏的情况下,你甚至会经历眩光。

我记得一位数寄屋的木匠给我上了一课。也就是说,眼睛的水平是非常重要的。例如,茶室通常是一个小空间,当你进入时,站着,感觉非常局促,非常幽闭恐惧。但是当你跪下和坐下时,你的眼睛水平很低,房间突然感觉高了很多。在西方的住宅里,你很少有这种感觉,因为西方的住宅通常不是围绕视点的根本变化而设计的;你达到的最低水平是当你坐在椅子上。

听竹居如何处理室内外之间的连续性?

通常,当我们谈到住宅的内部和外部的关系时,我们倾向于集中在窗户上,它们的打开方式,它们有多大,或者它们有多透明等等。然而,就我而言,正确的效果往往在很大程度上与外面事物的构成有关。

就听竹居而言,我们应该看一下住宅周围的植被是如何协调的。它的效果对于从内部看时如何创造深度感是极其重要的。

花园的空间可能相对较小,但由于植物,选择的品种和它们放置遮挡的方式,创造了一个神奇的深度。一种幻觉。与欧洲巴洛克时期的实验相比较,这种设计在内部和外部之间产生了一种特殊的关系。

在日本文化中,花园的构成强烈地以时间和空间为导向。你创造了一个延展的或围合的空间,并在其中;你仔细选择植物,以便在不同的季节发挥某些效果。我有一本关于听竹居的书,其中显示了你在夏季、春季、秋季和冬季的不同视图。你可以看到,在冬天,当雪落下时,通常暗哑的东西变得发光,黑色的树枝上有雪。在秋天,一切都呈现出不同色调的红与黄。在夏天和春天,你相应的拥有丰富多彩的的绿。这些情况中的每一种都对你的连续性或封闭性的感觉有不同的影响。

听竹居对1920年代的建筑生产有什么影响?

它在许多方面变得非常有影响力。它创造了一个预制模版化住宅的模板,这种住宅今天在日本仍然非常流行。当你观察他们如何组装,如何定义功能和空间,测量和流线,很多都来自藤井厚二的房子。

在藤井厚二之后不久,许多建筑师开始致力于将传统和西方元素融合到一栋住宅里。

例如,堀口舍己去荷兰学习了风格派,然后在1933年建造了冈田宅,这是一个现代主义的白盒子,其窗户和屋顶取自传统的民家。

另一位建筑师——前川国男(Kunio Maekawa)与勒-柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)合作,并将他的想法带回家。你可以发现弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的影响非常大,他被安东尼-雷蒙德带到了日本。他在美国与弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特一起工作,最终来到了日本。

在20世纪20年代,这些建筑师进行了大量的实验,引进了新的材料,如钢筋混凝土,新的生活概念,如家具,并将它们与日本的传统相混合。1920年是一个关键的年份。一群来自东京大学的学生决定举办一个展览,宣布摆脱保守主义,也摆脱西方建筑风格的支配。他们打算创造一些新的、自由的、能表达他们所处时代的东西,同时不背弃于日本身份。听竹居建于1928年。它反映了学生们的宣言——反映了如何在一个不断变化和发展的现代世界中保持日本的精神。

为了我在东京大学的博士论文,我记录并创建了一个学生毕设作品档案,从明治时期一直到伊东丰雄。通过这些,我可以观察到材料、建筑技术、社会习俗的转变,重要的是,引起这些变化的观念和影响。

环境问题在房子里是如何表达的?

藤井厚二博士是京都大学的环境系统教授。听竹居成为一个实验,关注于如何通过气流管理创造健康的家庭空间。

这种关注明确界定了各个空间的功能。它还对使用的材料以及房屋与地形的关系产生了影响。听竹居,用汉字写作 "聴竹居 ",意在"听,竹,居"。

那儿有一定的坡度,看着它,你可以想象空气会在哪里流动,以及这到了冬天和夏天会如何变化,相应地、适当地给房子通风。如果你看一下日本的一些老房子,它们是相当封闭的,由于潮湿和缺乏气流,可能会很闷,特别是在冬天。正如人们所说,京都的老町屋是为夏天设计的,因为你可以打开所有的东西完美地通风,在冬天就不那么容易了。此外,京都被群山环绕,留存了大量的热量,住宅内的空气质量从来没有像人们希望的那样健康。藤井厚二的创新是为了解决这些问题。

听竹居提出了什么可持续发展的模式?

现在每个人都对技术着迷,这本身并没有错,我只是认为,首先我们应该了解自己,作为人类,以及我们对周围环境的反应方式。我们一直在谈论零消费、零废物、零排放。很显然,我们可以设定目标并确定实现目标的方式。

然而,我认为重要的是,在所有这些计算和战略之上,不要忘记人。这意味着,作为建筑师,我们需要与文化紧密联系在一起。只有当我们在自己的行为中认识到这一点,可持续性才有可能。

通过阅读藤井厚二的孙子(小西信一)的回忆,你会接触到在听竹居的厨房里的记忆,在那里他被建筑引导着以某种方式行事。

他记得他们如何非常有效地收集有机废物,然后用它来给花园施肥。以一种非常微妙的方式,建筑可以在某种程度上指导你的日常生活,使你以不同的方式或以更好的方式来实践。

在日本,当你在一个花园里或在一条小路上时,你会发现小心翼翼地放在中间的一块石头,上面有一条绳子。通常情况下,这个信号意味着你不能再往前走了。有许多像这样的小信号,是日本人固有的行为,在我们的文化中根深蒂固。在我看来,像这样简单平静的标志,可能可以有效的引导人们做出某些对环境更有利的事情。

我认为这种软策略有可能比只谈数字和统计数字更成功。 听竹居之所以出名,是因为它在技术上的先进解决方案,以及藤井厚二通过写作对它们的强调。然而,我认为住宅内部还有更重要的品质,使其具有可持续性。也就是说,周围环境的质量,对传统行为模式的尊重,谨慎的创新滋养了好奇心,而没有压倒它。

听竹居是一个更广泛愿景的例子。这座住宅不仅本身有趣,而且与环境有关系。与丹下健三类似,藤井厚二也意识到,当你处理建筑时,它不仅仅是关于一个物体。它跨越了所有的尺度,与城市打交道。

我们已经走过了一个讨论风格的时代,来到了可持续发展的节点。我们的风格问题已经结束了吗?

人们似乎都在寻找真实性。由于气候的紧急情况,有必要审视自己,调查我们所处的位置,而不是讨论抽象的问题。在我们周围有复杂的事情发生。而且我们可以观察到,形式的话题在重要性的层次上滑落。当然,它仍将是讨论的一部分,但它将被审视能在多大程度上有助于更广泛的环境品质。

2021年11月06日

エルヴィン・ビライ: 『聴竹居』を選んでお話することにした理由は二つあります。

一つ目に、この住宅が環境工学的にサスティナビリティの問題にいち早く取り組んでいた住宅であること。もちろん国際的に最も議論されているテーマの一つですよね。

二つ目に、この住宅の一過性に強く惹かれたこと。日本の社会がダイナミックに変化していた時代の証左としての住宅。

その建築は日本と西洋、両方の特徴を備えていました。建築家 - 藤井厚二はメートル法を用いたパイオニアでした。住宅空間の設計に用いられる日本の伝統的な畳システムへの挑戦。それだけで慣習的な日本の構造システムとは全く異なるものになっています。ところがその全体的特徴は地域の感性からダイレクトに影響を受けており、優美な木造の茶室にもみられるような数寄屋的特性を持っています。

藤井厚二が『聴竹居』で融合を試みた西洋的特徴と日本的特徴とはどういったものですか?

20世紀が始まり最初の20年間、日本では国に相応しい様式や素材(木なのかレンガなのか)、さらには日常文化への西洋からの影響をどう取り入れるかが盛んに議論されていました。ヨーロッパからの技術や美学がかつてないほどに日本建築の論壇において存在感を増していったのです。

そういった状況でしたから、日本らしさ、つまり日本建築の特異性や国民性を守りつつ新しい状況に適応させることが、重要なカウンタートピックとなり得たのです。『聴竹居』より以前は、日本の貴族の慣例が規範となっていました。新しい官邸は二棟のペアで計画されたのです。日本の木造の伝統的な住宅。そしてそれに隣接する西洋のレンガ造りの住宅。

西洋の建物は、テーブルに椅子を並べて座るといったエキゾチックな活動のためのおしゃれな東屋として使われていました。異文化の新奇性を認めつつも同時に、日常生活における国民性の再認識や進化を怠っていたわけです。ですから、藤井厚二が二つの「様式」を一つの住宅に融合したのは驚きでしたし革新的でした。

その意図は、建物の外観からもすぐにわかります - コーナーを回る窓はモダニズムの特徴として代表的なものですね。内部に入ると電気照明が目に入ってきますが、この照明はまさにフランク・ロイド・ライトを意識したものです。彼は当時、東京で帝国ホテルを建設していました。さらに注目すべきは、ダイニングルームとリビングルームとの間に設けられた曲線の開口部です - どこかから引用されたもので、日本のものではありません。

それに、それぞれの部屋は特定の機能が与えられていて、内部の家具や建物内での部屋の位置関係が考慮されています。畳を敷くのではなく西洋的な測定法によって空間が作られているので規則的な感じがあるのですが、空間内の人や活動という次元にとっては抽象的になるのです。

最近ヘルマン・ムテジウスの『The English House』(1904年)に目を通していたのですが、『聴竹居』の平面計画はムテジウスの文章にインスピレーションを受けたのかもしれないと気づきました。私の知る限りですが、この本は1920年代の日本の建築家の間にも広まっていたものなのです。

住まいの質について分析をした周密な著作なのですが、そこで著者は、住宅内の特徴的な空間をそれぞれ独立した存在として記述しているのです。例えば藤井厚二は、寝室を住宅の中では離れた場所に設定していますよね - かなりアヴァンギャルドで「ヨーロッパ的」な判断です。

個々の部屋はどうやって決められているのでしょうか?好みによって機能を変えることはできないものなのでしょうか?

たいてい日本の住宅は、寝室とダイニングルームに大きな違いがありません。リビングルームがダイニングルームや寝室になったりもします。『聴竹居』においても理論的にはリビングルームとダイニングルームを取り替えることはできます。どちらもメインスペースにありますから。私は部屋の機能というものは、それがどこにあるのかによって決まるものだと思うのです。これは非常にロース的な家庭空間の考え方ですね。パブリックエリアとプライベートエリアは、開閉の度合いやアクセスのしやすさといった特徴によって区別されるものです。『聴竹居』が日本的な正当性から特出しているのは、こういった特徴があるからでしょう。

典型的な日本的要素で残っているものはありますか?

例えば薄暗い照明への好み。谷崎潤一郎の『陰影礼讃』(1977年)からもお分かりだと思いますが、日本では伝統的に空間の明暗を魅力的なものとして捉えます。『聴竹居』は近代的ドグマが推し進めるような光に満たされた白さではなく、むしろ暗さのある箱なのです。藤井厚二は伝統的な町屋のインテリアを想起させる素材を用いていますし、境界の作り方もまた、客を迎え入れる日本の儀式に深く根ざしているものだと思います。

客を迎え入れる儀式とは、どういうことですか?

日本の空間にはいつも階層や順序があって、どういった活動ができるかとか、どれくらい近づいていいのか、といったことがコントロールされています。ですから、さまざまな活動を許容する部屋があることはいいことなのです。客を招いた時に、どこから入るべきか説明を要するような境界を作る必要もありません。『聴竹居』の中心にある空間は、客を招くためのフォーマルな空間でもありますが、隣の部屋で活動が行われている時には回遊動線としても使われます。

このリビングルームが家の中での共同生活への関わり方にグラデーションを作ってくれるのです。そのおかげで自分自身の自律性や居場所としてのプライバシーを保ちながらも、それぞれの部屋では何が起こっているのかを感じることが可能なのです。許可を得るまでは、身体的にも聴覚的にも邪魔をしてはいけない。日本においての強力な社会的規範の特徴ですね。

西洋的な理解の仕方では、茶室の使われ方があまり明快に理解できていないかもしれません。

どう使うものなのか教えていただけますか?

今お話している住宅の場合、茶室自体は家の中にはありません。家の背後に小さなパビリオンがあって、そこに茶室としての十分な要素が備えられています - 茶室へといたる小道もあります。その小道は中に入る前に体を清める装置となるのです。

入り口は小さく、中には畳や床の間、客のための場所、それに茶を立てる場所が用意されています。座る場所は、客によって変化するものです。茶会は客を歓迎する方法であり、そこでは日常生活から平静と距離をとり、恒常的な自然の美しさに対峙するのです。

日本の畳システムによって作られた空間は、実際よりも大きく感じたり小さく感じたりするものなのでしょうか?

簡潔に答えを述べることは難しいのですが、この住宅には、西洋的な寸法と東洋的な雰囲気の組み合わせによる効果が見られます。『聴竹居』が大きく、天井が高く見えるのはおそらくメートル法によるためでしょう。例えば、日本の空間はたいてい天井がかなり低いのですが、フランク・ロイド・ライトもそのことを理解していて上手く設計に取り入れていましたね。日本やアメリカで建てられた彼の住宅を見にいくと、天井が低く軒も随分と長いことにすぐに気づきます。内部の光はとても控えめで、とりわけ眩しさは感じません。例えばですが、ミースの作品とは全然違うものですね。ファンズワース邸では光が床面いっぱいに差し込みますが、悪く言えば眩しいのです。

ある数寄屋大工が教えてくれたことを思い出します。要は目線の高さが非常に重要なのだと。たいてい茶室は小さな空間なので、立ったまま入ると窮屈で閉じ込められたように感じるのですが、膝をついて座ると目線が低くなり部屋が急に高く感じられます。目線の劇的な変化のない西洋の住宅では、こういった感覚を味わうことはありません。椅子に座った時に目線が一番低くなるくらいですからね。

『聴竹居』において内外の連続性については、どのようなことが考えられているのでしょうか?

内外の関係性のことを考えると普通は窓に着目しますよね。どう開けるかとか、どれくらい大きくするかとか、どれくらい透明なのかとか。本当は外部の構成によって決まるものだと私は考えています。

『聴竹居』の場合、まわりの植栽を気にして見てください。室内から見たときに奥行き感を作る非常に重要な要素となるのです。

庭自体の空間は比較的小さなものかもしれませんが、植物の選び方や配置の順序によって不思議にも奥行き感が生まれているのです。イリュージョンです。ヨーロッパにおけるバロック期の発明にも引けを取らない、内外の特別な関係を創出するデザインです。

日本文化における庭の構成では、時間と空間が強く意識されています。季節の変化による効果を想像しながら植物を選定し、広がりや囲われの感覚を作り出せるのです。私の持っている『聴竹居』の本には、春夏秋冬で異なる景色が映し出されています。冬に雪が降るといつもは暗がりにあるものが目に見えてきますね。雪が黒い枝に積もるときとか。秋にはあらゆるものが赤と黄色の色合いに染まり、夏と春には緑の色合いに染まる。こういった状況が広がりや囲われの感覚にさまざまな影響を与えるのです。

『聴竹居』が1920年代の建築産業に与えた影響はどういったものだったのでしょうか?

色々な点で大きな影響力があったと思います。日本で非常に普及している規格化住宅の雛形を作ったのです。組み立て方や機能や空間の割り振り方、それに寸法や動線などを見てみると、それらが藤井厚二のこの住宅に由来していることがわかります。

藤井厚二の直後から多くの建築家が、伝統的要素と西洋的要素を一つの住宅の中に融合するという課題に取り組むようになりました。例えば、堀口捨己はオランダでデ・ステイルを学んだ後、1933年に『岡田邸』を建てました。モダニズムの白い箱に伝統的な日本の屋根が乗っかっている建物です。

もう一人の建築家 - 前川國男はル・コルビュジエのもとで働き、その思想を日本へ持ち帰ってきた建築家です。それにアントニン・レーモンドのおかげでフランク・ロイド・ライトの影響が日本では根強いですね。彼はアメリカでライトのもとで働いた後、日本にやってきた建築家です。

1920年代の建築家たちは、鉄筋コンクリートといった新しい素材や家具にみられる新しい生活様式を取り入れ、日本の伝統と融合させる実験を繰り返していました。1920年は極めて重要な年です。東京大学の学生たちが、国の保守性や西洋の様式を優先する態度からの解放宣言を掲げて展覧会の開催を発案したのです。彼らは日本のアイデンティティを貶めることなく、自由な創作や彼らの生きる時代の表現を求めたのです。『聴竹居』は1928年に竣工しました。それは学生たちの宣言 - 常に変化と進化を続ける近代世界の中でいかにして日本人の精神を保つのか、という思いの投影されたものでした。

私の東京大学での博士論文は、明治時代から伊東豊雄に至るまでの学生の卒業制作をドキュメントとしてアーカイブ化したものでした。それらを通して、素材や建設技術、社会的習慣の変遷を追うことができました。そして何よりこうした変化をもたらす元となった認知や影響を理解することができました。

この住宅における環境へのこだわりはどこに表れていますか?

藤井厚二博士は、京都大学の環境システム学の教授でした。『聴竹居』は空気の流れをコントロールすることでいかに健康的な住空間を作れるかという実験だったのです。

個々の空間の機能が明確化されているのもそのためです。素材の使い方や地形との関係も示唆的です。『Cho-chiku-kyo』は漢字で書くと『聴竹居』ですから、聴く、竹、住まい、という意味があるのです。

敷地の傾斜を見ていただくと、空気がどこを流れ、その流れが冬と夏とではどう変化するのかが想像できると思います。それに応じて適切に家を換気できるのです。日本の古い家屋を見るとかなり閉鎖的であることがわかると思います。特に冬場は湿気と風通しの悪さで、むっとして息の詰まるほどです。京都の古い町屋は夏をもって旨とすべし、と言われているように全てをオープンにすれば問題なく換気することができるのですが、冬にはそう簡単にいきません。それに京都は山に囲まれているので、家の中の空気は熱がこもってしまい健康なものとは言えません。藤井厚二のイノベーションはこうした問題の解決を目指したものでした。

サスティナビリティのためのモデルとして『聴竹居』は何を提示しているのでしょうか?

今では誰もがテクノロジーに夢中で、それ自体が間違っているとは思いません。ですが、まずは人間としての私たちを理解し環境に対してどう応えていくべきかを考えるべきだと思います。私たちは常々、消費ゼロ、廃棄ゼロ、排出ゼロ、と言っているわけですが、目標を設定して達成への道のりを定めることは難しくないはずです。

大事なのは、こうした統計や戦略よりも私たちが人間であることを忘れないことだと思います。つまり建築家としての私たちが、文化と密接な関係を持たなくてはいけない。サスティナビリティは、私たち自身の振る舞いを認識することによってのみ可能なものなのでしょう。

藤井厚二の孫(小西信一)の回想録を読むと、彼が『聴竹居』の台所にいたときの記憶が描かれています。そこで彼は、建築に導かれるようにして行っていたある振る舞い、つまり、生ゴミを収集し庭の肥料にすることがいかに効率的であったかを思い出すのです。なんてことはない方法で、建築は異なる視点から日常生活への実践を示唆してくれるものです。

日本では、庭や小道を歩いていると道の真ん中に縄でくくられた石が置かれているのを見ることがあります。これ以上先に進んではいけないというサインです。日本人の振る舞いに特有なこうした小さなサインはたくさんありますし、私たちの文化に刻み込まれているものなのです。こうしたシンプルで穏やかなサインは、環境にとって良い行いを私たちに導いてくれるはずなのです。

数字や統計の話ばかりするよりも、こうしたソフト面での対策の方が可能性があるのではないでしょうか。『聴竹居』が有名になったのは、技術的に高度な解決策を提示したことに加えて、藤井厚二がそのことを文章で強調していたからです。ですが、それよりもサスティナブルという観点で重要な特質がこの住宅にはあるのだと思います。要するに、周辺環境の質、伝統的な振る舞いへの敬意、そして抑制された好奇心に育まれた控えめなイノベーション、ということでしょうか。

『聴竹居』は広い視野をもった事例と言えるでしょう。それ自体が興味深い住宅でありながら、環境との関係を保持している。つまり丹下健三と同じように、建築を扱うことは、ただのオブジェクトとしてではなく、あらゆるスケールを横断し都市との関わりを持つことなのだ、ということに藤井厚二も意識的であったのです。

今日の議題は、様式からサスティナビリティへと変わっていったということですが、様式の問題は解決されたのでしょうか?

人々はオーセンティックなものを求めているようです。気候非常事態によって、抽象的な問題を議論するよりも、私たち自身を見つめ直し、私たちの立ち位置を模索する必要が出てきたのです。私たちの周りには複雑なことが起こっていますし、その中で形の議論に対する比重が下降傾向にあるのはお分かりでしょう。もちろん議題の一つとして残るとは思いますが、より広域な環境にとって、それがどれほど貢献的なものなのかはわかりませんね。

2021年11月06日

Erwin Viray: I have chosen to speak about Chochikukyo for two reasons.

Firstly, it seems to be one of the earliest houses to address, through environmental engineering, the issue of sustainability, which, as we are all aware of, is currently one of the most discussed international topics.

Secondly, I was always very attracted by its transitory character. As a house it's a testimony to a period of dynamic change within Japanese society. Its architecture has both Japanese and Western features. The architect - Koji Fujii was a pioneer in the use of the metric measurement system, which challenged the traditional Japanese Tatami language of spatial planning in residential buildings. Only because of this, the house already feels very different from typical Japanese structures. Nevertheless, its overall character stems directly from the local sensibility and has a lot in common with Sukiya style (1574-1867) architecture - which was partly present in elegant wooden tea ceremony pavilions.

WHAT WERE THE WESTERN AND JAPANESE FEATURES THAT KOJI FUJII MIXED IN CHOCHIKUKYO?

The first two decades of the 20th century in Japan were a period of vivid discussion on the appropriate style, materiality (wood or bricks) and inclusion of western influences in everyday culture. At the time, European techniques and aesthetics were becoming ever more present in the Japanese architectural debate.

As such, protecting Japan-ness, i.e., the specificity and national character of Japanese architecture, while adapting it to the new conditions, became an important counter topic. Before Chochikukyo was built, the example was set by Japanese nobility, who, when erecting new official palaces, built them in pairs; a Japanese wooden, traditional house and a Western brick version next to it.

The Western building served as a sort of fashionable pavilion for exotic activities like sitting at a table with chairs etc., an acknowledgement of the novel developments of another culture but at the same time a failure to re-understand or evolve the national way of life. It was therefore surprising, and innovative, that Koji Fujii combined these two „styles” in one house.

This intention is immediately visible from the exterior of the building - windows wrap around the corners, a well-known modernistic feature, and upon entering, you see electric lighting, directly inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, who was building the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo at that time. Also noticeable, is the curved wall opening between the dining room and the living room - a quotation, and something that had not been done in Japan before.

Moreover, the rooms have a specific function, related to the furniture they contain and their location in the house. Spaces were not defined by the laying of mats, but by western measurements that are at once precise but then also abstract to the dimensions of people and cultural movements in space.

I recently skimmed through the book The English House (1904) by Herman Muthesius and realised that the layout of Chochikukyo could have been inspired by Muthesius’ writing. As far as I know the publication circulated among architects in Japan during the 20’s.

It’s a meticulous work, analysing the qualities of dwellings in which the author describes each specific space of a house as a separate entity. For example, in Chochikukyo the bedrooms are clearly defined in a separate part of the house – which would have been a very avant-guard or ‘European’ decision.

HOW ARE THE INDIVIDUAL ROOMS DEFINED? COULDN’T YOU CHANGE THE FUNCTIONS ACCORDING TO YOUR PREFERENCES?

Usually in Japanese houses, bedrooms and the dining room are not that much different. A living room can be a dining room, can be a bedroom etc. In Chochikukyo you could theoretically swop the living with the dining room, they are both part of one main space, however, as far as I am concerned, the functions are meant to be where they are. It was very much a Loos’ian way of thinking about domestic space. The public and the private areas are distinguished in their character, grade of opening and access. I think, it was a feature that pushed Chochikukyo even further from the Japanese orthodoxy.

WHAT TYPICAL JAPANESE ELEMENTS REMAIN IN THE BUILDING?

For instance, the preference to have rather dim light. As you might know from the book In Praise of Shadows (1977) by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, in the Japanese context, the spaces between lightness and darkness are traditionally perceived as attractive. Chochikukyo is not a white box soaked with light, as the modern dogma might have prompted, it is instead darker, with Koji Fujii using materials that recalled the interiors of traditional Machiyas. The way of using the thresholds between spaces is also deeply rooted in the ceremonial way of receiving guests in Japan.

WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY CEREMONIAL WAY OF RECEIVING GUESTS?

In Japan, there is always a hierarchy or sequence which determines how activities and levels of intimacy are controlled. It’s better to make a room suitable for a diverse spectrum of activities and as such, you would avoid creating thresholds that require guests to receive invitations or directions to enter. The central space in Chochikukyo is a formal space for receiving guests, but it also allows circulation if the adjacent spaces are occupied by other activities.

This so-called living room enables the gradation of involvement of spaces in the common life of the house. Thanks to it, you can be aware of what happens in each room, whilst maintaining your autonomy and the privacy of the place you are in. The compartmentalisation of the activities and the spaces enables a subtle mediation of in-between situations. You never intrude either physically or acoustically into a space before being allowed to do so. It’s a very strong characteristic of Japanese social norms.

IN A WESTERN CONTEXT, IT IS PROBABLY NOT VERY CLEAR HOW A TEA HOUSE IS USED. HOW DOES IT WORK?

In the case of the house we discuss, the teahouse is not in the house itself. There is a smaller pavilion behind the house. It has the proper components of a teahouse - there is a pathway to reach it and the necessary devices to purify yourself before entering. The entrance is small. Inside you see Tatami mats, the tokonoma, the place of honour, and the place where the host prepares the tea. The seating is arranged based on who is the guest. A tea ceremony is an elaborate way of celebrating the presence of guests, peacefully distant from everyday activities, and relative to the ever-present beauty of nature.

DOES THE SPACE BUILT ACCORDING TO THE JAPANESE TATAMI SYSTEM SEEM BIGGER, OR SMALLER THAN IT REALLY IS?

It is difficult to answer directly, the effect of the house is result of a combination of western measurements and eastern atmospheric conditions. Chochikukyo seems to be bigger and higher, probably because of the metric system it follows. For instance, ceiling height, in Japanese space is usually quite low, and is a character that Frank Lloyd Wright equally captured and adopted successfully in some of his buildings. If you go to visit the houses he built in Japan or to some of his houses in the US, you immediately see that the ceiling is low, and the eaves are longer than you would expect. The quality of light inside becomes very subdued, the environment is never particularly bright. It is very different from the works by Mies for instance. In the Farnsworth house light penetrates the plan fully and at worst, you experience even glare.

I remember a lesson that one Sukiya carpenter gave me. Namely, that the level of the eye is very important. The Tea room for example, is usually a small space and when you enter, standing, it feels very confined, very claustrophobic. But when you kneel and sit down your eye level is very low, and the room suddenly feels much higher. You rarely have this feeling in Western houses which are not usually designed around radical changes in viewpoint; the lowest level you reach is when you sit down on a chair.

HOW DOES CHOCHIKUKYO DEAL WITH THE CONTINUITY BETWEEN INSIDE AND OUTSIDE?

Usually when we speak about the relationship between inside and outside in a house we tend to concentrate on windows, the way they open, how big, or transparent they are and so on. However, as far as I am concerned, the right effect is often very much bound to the composition of what is outside.

In case of Chochikukyo one should look at how the vegetation is coordinated around the house. Its effect is extremely important on how a sense of depth is created when looking from inside.

The space of the garden might be relatively small, but because of the plants, the species that were selected and the way they have been placed behind each other, a magical depth is created. An illusion. Comparable to the experiments of the Baroque period in Europe, the design produces a special relationship between the inside and outside.

In Japanese culture, the composition of the garden is strongly orientated to time and space. You create a widening or an enclosure and within it; you choose the plants carefully to perform certain effects in different seasons. I have a book on Chochikukyo, that shows the differences of views you have in summer, spring, autumn and winter. You can see that in the winter when the snow falls, what normally is dark becomes luminous, you have the snow on the black branches. In autumn, everything is in different shades of red and yellow. In summer and spring, you have instead diverse shades of green. Each of these situations has a different impact on your feeling of continuity or enclosure.

WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF CHOCHIKUKYO ON THE ARCHITECTURAL PRODUCTION IN THE 1920’S?

It became very influential in many ways. It created a template for prefabricated modular houses, that are today still very popular in Japan. When you look at how they are assembled and how they define functions and spaces, measurements and circulation, a lot comes from this house by Koji Fujii.

Shortly after Koji Fujii, many architects started to work on the task of melding both traditional and western elements in to one house.

For instance, Sutemi Horiguchi went to Holland and studied De Stijl before going on to build the Okada House in 1933, which was a combination of a modernist white box with the windows and roof taken from a traditional Minka.

Another architect - Kunio Maekawa, worked with Le Corbusier and brought his ideas home. You could find a very strong influence of Frank Lloyd Wright brought over to Japan by Antonin Raymond. He went to work with FLW in the USA and eventually ended up in Japan.

During the 1920s these architects were experimenting a lot, introducing new materials like reinforced concrete, new concepts of living, like furniture, and mixing them with Japanese traditions. 1920 was a pivotal year. A group of students from the University of Tokyo decided to make an exhibition declaring freedom from the conservatism, but also from dominance of Western styles of architecture. They intended to create something free and expressive of the age they lived in, whilst not discrediting Japanese identity. Chochikukyo was built in 1928. It reflected the student’s declaration - a reflection of how to keep the Japanese spirit in an ever changing and evolving modern world.

For my PhD dissertation at the University of Tokyo, I documented and created an archive of student graduation works from Meiji period all the way up to Toyo Ito. Through this I could observe the transformation in materials, construction techniques, social customs and importantly, the perceptions and the influences that gave rise to these changes.

HOW ARE ENVIRONMENTAL PREOCCUPATIONS EXPRESSED IN THE HOUSE?

Dr Koji Fujii was a professor of environmental systems at the University in Kyoto. Chochikukyo became an experiment centered on how you can create healthy domestic spaces, through the management of airflow.

This preoccupation clearly defined the function of individual spaces. It also had implications on the materials used, and the relationship of the house to the terrain. Chochikukyo, written in Chinese characters 聴竹居means: “listen, bamboo, dwelling.”

There’s a certain slope, looking at it, you can imagine where the air would flow and how this would change during the winter and summer, ventilating the house accordingly and properly. If you look at some of older houses in Japan, they are quite closed, and can be stuffy due to humidity and lack of airflow, especially in winter. The old Machiyas in Kyoto are designed for summer, as people say, because you can open everything and ventilate perfectly, in the winter it was not so easy. Moreover, Kyoto, surrounded by mountains, retains a lot of heat, and the air quality in the houses was never as healthy as one would have wished it to be. Koji Fujii’s innovations were aimed at addressing these issues.

WHAT MODEL OF SUSTAINABILITY DOES CHOCHIKUKYO PROPOSE?

Now everybody is fascinated with technology, and it’s not wrong per se, I just think that first we should understand ourselves, as human beings, and the ways in which we react to the environment around us. We speak all the time about zero consumption, zero waste, zero emission. It’s clear we can set targets and determine ways of achieving them.

However, what I think is important, above all these calculations and strategies, is not to forget the human being. That means, as architects, we need to operate in tight connection with culture. Sustainability is only possible if we acknowledge it in our own behavior.

Reading through the recollections of Koji Fujii’s grandchild (Konishi Shinichi) you encounter memories of being in the kitchen at Chochikukyo, where he was guided by architecture to behave in a certain way.

He would remember how it was very efficient for them to collect the organic waste, and later use it to fertilise the garden. In a very subtle way, architecture can somehow guide you through everyday life and make you practice things differently or perhaps in a better light.

Often in Japan, when you’re in a garden or on a pathway you will find, placed carefully in the middle, a stone with a rope on it. Usually, this sign means that you are not to go further. There are many little signals like this that are inherent in Japanese behaviour, engrained in our culture. In my mind, simple calm signs such as these, could be useful in guiding people to do certain things that are better for the environment.

I see this kind of soft strategy potentially more successful than talking only about numbers and statistics. Chochikukyo became famous because of its technically advanced solutions and the emphasis Koji Fuji put on them through his writing. However, I think there are more important qualities within the house, that make it sustainable. Namely, the qualities of the environment around, the respect towards patterns of traditional behaviour, discreet innovations that nourished curiosity without overwhelming it.

Chochikukyo is an example of a broader vision. Not only is the house interesting itself, but it has a relationship to its environment. Similarly, to Kenzo Tange, Koji Fuji was aware that when you deal with architecture, it’s not just about an object. It crosses all scales and deals with the city.

WE HAVE PASSED THROUGH AN EPOCH OF DISCUSSION ABOUT STYLE AND ARRIVED AT THE POINT OF SUSTAINABILITY. ARE WE DONE WITH STYLISTIC ISSUES?

People seem to be looking for authenticity. Because of the climate emergency there is a need to look at ourselves and investigate where we’re standing, rather than discussing about abstract issues. There are complex things happening around us. And we can observe that the topic of form slides down the hierarchy of importance. It will of course remain part of the discussion, but it will be questioned to what extent it supports the quality of the much wider environment.

06.11.2021

埃尔文-维雷 我选择谈论听竹居有两个原因。

首先,它似乎是最早通过环境工程解决可持续性问题的住宅之一,正如我们所知,可持续发展是目前讨论最多的国际性话题之一。

其次,我一直被它的过渡性特质所吸引。作为一栋住宅,它见证了日本社会的一个动态变化时期。

它的建筑同时具有日本和西方的特点。建筑师藤井厚二是使用公制测量系统的先驱,这对日本传统的住宅建筑空间规划上使用的榻榻米度量构成了挑战。仅仅因为这一点,已经能感受到这所住宅与典型的日本结构有着很大的不同。然而,它的整体特征直接源于当地的感觉,与数寄屋风格(1574-1867)的建筑有很多共同之处——这部分的呈现于优雅的木制茶室中。

藤井厚二在听竹居中混合了哪些西方和日本的特点?

20世纪头20年的日本,活跃着关于合适的风格、材料(木头或砖)和在日常文化中纳入西方影响的讨论。当时,欧洲的技术和美学越来越多地出现在日本的建筑讨论中。

因此,保护日本性,即日本建筑的特殊性和民族性,同时使其适应新的条件,成为一个重要的对立话题。在听竹居建成之前,日本贵族树立了榜样,他们在建造新的官方宫殿时,都是成对建造的;一座日本的木制传统住宅和旁边的西方砖制住宅。

西方的建筑作为一种用于异国情调活动的时尚的场馆,如坐在有椅子的桌子前等,这是对另一种文化新发展的承认,但同时也是对民族生活方式的重新理解或发展的失败。因此,藤井厚二将这两种 "风格 "结合在一栋住宅中是令人惊讶的,也是创新的。

这种意图从建筑的外部就可以看出来——窗户环绕着角落,这是一个著名的现代主义特征,一进门就可以看到电灯,直接受到弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的启发,他当时正在东京建造帝国酒店。同样值得注意的是,餐厅和起居室之间的弧形墙体开口——这是一种引用,也是以前在日本没有做过的事情。

此外,房间的规划具有非常具体的功能。卧室在住宅的一个独立部分(删除并移至下一段)。房间有特定的功能,与其中的家具和房间在住宅中的位置有关。空间不是由铺设榻榻米来定义的,而是由西方的测量方式,这些测量方式一方面精确,一方面对于人和文化活动在空间中的尺度是抽象的。

我最近浏览了赫尔曼-穆特修斯(Herman Muthesius)的《英国人的住宅》(1904)一书,意识到听竹居的布局可能是受到穆特修斯的启发。据我所知,该出版物在20年代的日本建筑师中流传。

这是一部细致的作品,分析了住宅的品质,其中作者将住宅的每个具体空间都描述为一个独立的实体。例如,藤井厚二的卧室被明确定义为住宅的一个独立部分——这本来是一个非常前卫或 "欧洲 "的决定。

每个房间是如何定义的?你不能根据自己的喜好来改变功能吗?

通常在日本的住宅中,卧室和餐厅没有太大的区别。客厅可以是餐厅,也可以是卧室等等。在听竹居,理论上你可以把客厅和餐厅调换一下,它们都是一个主要空间的一部分,然而,就我而言,这些功能就应该在那里。这在很大程度上是路斯对家庭空间的一种思考方式。公共区域和私人区域在其特征、开放程度和可达性方面是有区别的。我认为,这是一个将听竹居进一步推离日本正统观念的特征。

建筑中保留了哪些典型的日本元素?

例如,对相当幽暗的光线的偏好。正如你可能从谷崎润一郎的《阴翳礼赞》(1977)一书中知道的,在日本语境中,明暗之间的空间传统上被认为是有吸引力的。听竹居并不是像现代主义教条所提示的那样,是一个浸泡在光线中的白色盒子,相反,它更黑暗,藤井厚二使用的材料让人想起传统町屋的内饰。在空间之间的使用门槛的方式也深深地扎根于日本的待客礼仪。

你说的待客礼仪是什么意思?

在日本,总是有一个层级或顺序,去决定如何控制活动和亲密关系的等级。最好是使房间适合多样化的活动,因此,你会避免创造那种需要客人受到邀请或者指示才能进入的门槛。听竹居的中央空间是一个接待客人的正式空间,但如果相邻的空间被其他活动占据,它也允许被作为交通空间使用。

这个所谓的起居室使得不同空间在住宅共同生活中的参与程度有所分级。由于它的存在,你可以意识到每个房间里发生的事情,同时保持你的自主性和所在之处的隐私。活动和空间的分隔使得一种微妙的介于两者之间的情况成为可能。在被允许之前,你永远不会从身体上或声音上闯入一个空间。这是日本社会规范的一个非常强烈的特点。

在西方背景下,可能不太清楚茶室是怎么使用的。它是如何运作的呢?

以我们所讨论的这所住宅为例,茶室不位于住宅主体之中。住宅后面有一个较小的别馆。它有茶室的适当组成部分——有一条通往茶室的小径,以及进入前净化自己的必要装置。入口很小。在里面你可以看到榻榻米、床之间,荣誉的地方,以及主人准备茶的地方。座位是根据谁是客人来安排的。茶道是庆祝客人光临的一种精心设计的方式,平和地远离日常活动,并与自然界的永恒之美相对。

根据日本榻榻米系统建造的空间看起来比实际情况大,还是小?

很难直接回答,住宅的效果是西方的测量方式和东方的氛围相结合的结果。听竹居似乎更大更高,可能是因为它遵循的公制系统。例如,天花板的高度,在日本的空间通常是相当低的,这也是弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特在他的一些建筑中同样捕捉并成功采用的特征。如果你去参观他在日本建造的住宅或他在美国的一些住宅,你会立即看到天花板很低,而且屋檐比你想象的要长。内部的光线品质变得非常柔和,环境从来不是特别明亮。这与密斯等人的作品非常不同。在范斯沃斯宅中,光线完全穿透了整层,在最坏的情况下,你甚至会经历眩光。

我记得一位数寄屋的木匠给我上了一课。也就是说,眼睛的水平是非常重要的。例如,茶室通常是一个小空间,当你进入时,站着,感觉非常局促,非常幽闭恐惧。但是当你跪下和坐下时,你的眼睛水平很低,房间突然感觉高了很多。在西方的住宅里,你很少有这种感觉,因为西方的住宅通常不是围绕视点的根本变化而设计的;你达到的最低水平是当你坐在椅子上。

听竹居如何处理室内外之间的连续性?

通常,当我们谈到住宅的内部和外部的关系时,我们倾向于集中在窗户上,它们的打开方式,它们有多大,或者它们有多透明等等。然而,就我而言,正确的效果往往在很大程度上与外面事物的构成有关。

就听竹居而言,我们应该看一下住宅周围的植被是如何协调的。它的效果对于从内部看时如何创造深度感是极其重要的。

花园的空间可能相对较小,但由于植物,选择的品种和它们放置遮挡的方式,创造了一个神奇的深度。一种幻觉。与欧洲巴洛克时期的实验相比较,这种设计在内部和外部之间产生了一种特殊的关系。

在日本文化中,花园的构成强烈地以时间和空间为导向。你创造了一个延展的或围合的空间,并在其中;你仔细选择植物,以便在不同的季节发挥某些效果。我有一本关于听竹居的书,其中显示了你在夏季、春季、秋季和冬季的不同视图。你可以看到,在冬天,当雪落下时,通常暗哑的东西变得发光,黑色的树枝上有雪。在秋天,一切都呈现出不同色调的红与黄。在夏天和春天,你相应的拥有丰富多彩的的绿。这些情况中的每一种都对你的连续性或封闭性的感觉有不同的影响。

听竹居对1920年代的建筑生产有什么影响?

它在许多方面变得非常有影响力。它创造了一个预制模版化住宅的模板,这种住宅今天在日本仍然非常流行。当你观察他们如何组装,如何定义功能和空间,测量和流线,很多都来自藤井厚二的房子。

在藤井厚二之后不久,许多建筑师开始致力于将传统和西方元素融合到一栋住宅里。

例如,堀口舍己去荷兰学习了风格派,然后在1933年建造了冈田宅,这是一个现代主义的白盒子,其窗户和屋顶取自传统的民家。

另一位建筑师——前川国男(Kunio Maekawa)与勒-柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)合作,并将他的想法带回家。你可以发现弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的影响非常大,他被安东尼-雷蒙德带到了日本。他在美国与弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特一起工作,最终来到了日本。

在20世纪20年代,这些建筑师进行了大量的实验,引进了新的材料,如钢筋混凝土,新的生活概念,如家具,并将它们与日本的传统相混合。1920年是一个关键的年份。一群来自东京大学的学生决定举办一个展览,宣布摆脱保守主义,也摆脱西方建筑风格的支配。他们打算创造一些新的、自由的、能表达他们所处时代的东西,同时不背弃于日本身份。听竹居建于1928年。它反映了学生们的宣言——反映了如何在一个不断变化和发展的现代世界中保持日本的精神。

为了我在东京大学的博士论文,我记录并创建了一个学生毕设作品档案,从明治时期一直到伊东丰雄。通过这些,我可以观察到材料、建筑技术、社会习俗的转变,重要的是,引起这些变化的观念和影响。

环境问题在房子里是如何表达的?

藤井厚二博士是京都大学的环境系统教授。听竹居成为一个实验,关注于如何通过气流管理创造健康的家庭空间。

这种关注明确界定了各个空间的功能。它还对使用的材料以及房屋与地形的关系产生了影响。听竹居,用汉字写作 "聴竹居 ",意在"听,竹,居"。

那儿有一定的坡度,看着它,你可以想象空气会在哪里流动,以及这到了冬天和夏天会如何变化,相应地、适当地给房子通风。如果你看一下日本的一些老房子,它们是相当封闭的,由于潮湿和缺乏气流,可能会很闷,特别是在冬天。正如人们所说,京都的老町屋是为夏天设计的,因为你可以打开所有的东西完美地通风,在冬天就不那么容易了。此外,京都被群山环绕,留存了大量的热量,住宅内的空气质量从来没有像人们希望的那样健康。藤井厚二的创新是为了解决这些问题。

听竹居提出了什么可持续发展的模式?

现在每个人都对技术着迷,这本身并没有错,我只是认为,首先我们应该了解自己,作为人类,以及我们对周围环境的反应方式。我们一直在谈论零消费、零废物、零排放。很显然,我们可以设定目标并确定实现目标的方式。

然而,我认为重要的是,在所有这些计算和战略之上,不要忘记人。这意味着,作为建筑师,我们需要与文化紧密联系在一起。只有当我们在自己的行为中认识到这一点,可持续性才有可能。

通过阅读藤井厚二的孙子(小西信一)的回忆,你会接触到在听竹居的厨房里的记忆,在那里他被建筑引导着以某种方式行事。

他记得他们如何非常有效地收集有机废物,然后用它来给花园施肥。以一种非常微妙的方式,建筑可以在某种程度上指导你的日常生活,使你以不同的方式或以更好的方式来实践。

在日本,当你在一个花园里或在一条小路上时,你会发现小心翼翼地放在中间的一块石头,上面有一条绳子。通常情况下,这个信号意味着你不能再往前走了。有许多像这样的小信号,是日本人固有的行为,在我们的文化中根深蒂固。在我看来,像这样简单平静的标志,可能可以有效的引导人们做出某些对环境更有利的事情。

我认为这种软策略有可能比只谈数字和统计数字更成功。 听竹居之所以出名,是因为它在技术上的先进解决方案,以及藤井厚二通过写作对它们的强调。然而,我认为住宅内部还有更重要的品质,使其具有可持续性。也就是说,周围环境的质量,对传统行为模式的尊重,谨慎的创新滋养了好奇心,而没有压倒它。

听竹居是一个更广泛愿景的例子。这座住宅不仅本身有趣,而且与环境有关系。与丹下健三类似,藤井厚二也意识到,当你处理建筑时,它不仅仅是关于一个物体。它跨越了所有的尺度,与城市打交道。

我们已经走过了一个讨论风格的时代,来到了可持续发展的节点。我们的风格问题已经结束了吗?

人们似乎都在寻找真实性。由于气候的紧急情况,有必要审视自己,调查我们所处的位置,而不是讨论抽象的问题。在我们周围有复杂的事情发生。而且我们可以观察到,形式的话题在重要性的层次上滑落。当然,它仍将是讨论的一部分,但它将被审视能在多大程度上有助于更广泛的环境品质。

2021年11月06日

エルヴィン・ビライ: 『聴竹居』を選んでお話することにした理由は二つあります。

一つ目に、この住宅が環境工学的にサスティナビリティの問題にいち早く取り組んでいた住宅であること。もちろん国際的に最も議論されているテーマの一つですよね。

二つ目に、この住宅の一過性に強く惹かれたこと。日本の社会がダイナミックに変化していた時代の証左としての住宅。

その建築は日本と西洋、両方の特徴を備えていました。建築家 - 藤井厚二はメートル法を用いたパイオニアでした。住宅空間の設計に用いられる日本の伝統的な畳システムへの挑戦。それだけで慣習的な日本の構造システムとは全く異なるものになっています。ところがその全体的特徴は地域の感性からダイレクトに影響を受けており、優美な木造の茶室にもみられるような数寄屋的特性を持っています。

藤井厚二が『聴竹居』で融合を試みた西洋的特徴と日本的特徴とはどういったものですか?

20世紀が始まり最初の20年間、日本では国に相応しい様式や素材(木なのかレンガなのか)、さらには日常文化への西洋からの影響をどう取り入れるかが盛んに議論されていました。ヨーロッパからの技術や美学がかつてないほどに日本建築の論壇において存在感を増していったのです。

そういった状況でしたから、日本らしさ、つまり日本建築の特異性や国民性を守りつつ新しい状況に適応させることが、重要なカウンタートピックとなり得たのです。『聴竹居』より以前は、日本の貴族の慣例が規範となっていました。新しい官邸は二棟のペアで計画されたのです。日本の木造の伝統的な住宅。そしてそれに隣接する西洋のレンガ造りの住宅。

西洋の建物は、テーブルに椅子を並べて座るといったエキゾチックな活動のためのおしゃれな東屋として使われていました。異文化の新奇性を認めつつも同時に、日常生活における国民性の再認識や進化を怠っていたわけです。ですから、藤井厚二が二つの「様式」を一つの住宅に融合したのは驚きでしたし革新的でした。

その意図は、建物の外観からもすぐにわかります - コーナーを回る窓はモダニズムの特徴として代表的なものですね。内部に入ると電気照明が目に入ってきますが、この照明はまさにフランク・ロイド・ライトを意識したものです。彼は当時、東京で帝国ホテルを建設していました。さらに注目すべきは、ダイニングルームとリビングルームとの間に設けられた曲線の開口部です - どこかから引用されたもので、日本のものではありません。

それに、それぞれの部屋は特定の機能が与えられていて、内部の家具や建物内での部屋の位置関係が考慮されています。畳を敷くのではなく西洋的な測定法によって空間が作られているので規則的な感じがあるのですが、空間内の人や活動という次元にとっては抽象的になるのです。

最近ヘルマン・ムテジウスの『The English House』(1904年)に目を通していたのですが、『聴竹居』の平面計画はムテジウスの文章にインスピレーションを受けたのかもしれないと気づきました。私の知る限りですが、この本は1920年代の日本の建築家の間にも広まっていたものなのです。

住まいの質について分析をした周密な著作なのですが、そこで著者は、住宅内の特徴的な空間をそれぞれ独立した存在として記述しているのです。例えば藤井厚二は、寝室を住宅の中では離れた場所に設定していますよね - かなりアヴァンギャルドで「ヨーロッパ的」な判断です。

個々の部屋はどうやって決められているのでしょうか?好みによって機能を変えることはできないものなのでしょうか?

たいてい日本の住宅は、寝室とダイニングルームに大きな違いがありません。リビングルームがダイニングルームや寝室になったりもします。『聴竹居』においても理論的にはリビングルームとダイニングルームを取り替えることはできます。どちらもメインスペースにありますから。私は部屋の機能というものは、それがどこにあるのかによって決まるものだと思うのです。これは非常にロース的な家庭空間の考え方ですね。パブリックエリアとプライベートエリアは、開閉の度合いやアクセスのしやすさといった特徴によって区別されるものです。『聴竹居』が日本的な正当性から特出しているのは、こういった特徴があるからでしょう。

典型的な日本的要素で残っているものはありますか?

例えば薄暗い照明への好み。谷崎潤一郎の『陰影礼讃』(1977年)からもお分かりだと思いますが、日本では伝統的に空間の明暗を魅力的なものとして捉えます。『聴竹居』は近代的ドグマが推し進めるような光に満たされた白さではなく、むしろ暗さのある箱なのです。藤井厚二は伝統的な町屋のインテリアを想起させる素材を用いていますし、境界の作り方もまた、客を迎え入れる日本の儀式に深く根ざしているものだと思います。

客を迎え入れる儀式とは、どういうことですか?

日本の空間にはいつも階層や順序があって、どういった活動ができるかとか、どれくらい近づいていいのか、といったことがコントロールされています。ですから、さまざまな活動を許容する部屋があることはいいことなのです。客を招いた時に、どこから入るべきか説明を要するような境界を作る必要もありません。『聴竹居』の中心にある空間は、客を招くためのフォーマルな空間でもありますが、隣の部屋で活動が行われている時には回遊動線としても使われます。

このリビングルームが家の中での共同生活への関わり方にグラデーションを作ってくれるのです。そのおかげで自分自身の自律性や居場所としてのプライバシーを保ちながらも、それぞれの部屋では何が起こっているのかを感じることが可能なのです。許可を得るまでは、身体的にも聴覚的にも邪魔をしてはいけない。日本においての強力な社会的規範の特徴ですね。

西洋的な理解の仕方では、茶室の使われ方があまり明快に理解できていないかもしれません。

どう使うものなのか教えていただけますか?

今お話している住宅の場合、茶室自体は家の中にはありません。家の背後に小さなパビリオンがあって、そこに茶室としての十分な要素が備えられています - 茶室へといたる小道もあります。その小道は中に入る前に体を清める装置となるのです。

入り口は小さく、中には畳や床の間、客のための場所、それに茶を立てる場所が用意されています。座る場所は、客によって変化するものです。茶会は客を歓迎する方法であり、そこでは日常生活から平静と距離をとり、恒常的な自然の美しさに対峙するのです。

日本の畳システムによって作られた空間は、実際よりも大きく感じたり小さく感じたりするものなのでしょうか?

簡潔に答えを述べることは難しいのですが、この住宅には、西洋的な寸法と東洋的な雰囲気の組み合わせによる効果が見られます。『聴竹居』が大きく、天井が高く見えるのはおそらくメートル法によるためでしょう。例えば、日本の空間はたいてい天井がかなり低いのですが、フランク・ロイド・ライトもそのことを理解していて上手く設計に取り入れていましたね。日本やアメリカで建てられた彼の住宅を見にいくと、天井が低く軒も随分と長いことにすぐに気づきます。内部の光はとても控えめで、とりわけ眩しさは感じません。例えばですが、ミースの作品とは全然違うものですね。ファンズワース邸では光が床面いっぱいに差し込みますが、悪く言えば眩しいのです。

ある数寄屋大工が教えてくれたことを思い出します。要は目線の高さが非常に重要なのだと。たいてい茶室は小さな空間なので、立ったまま入ると窮屈で閉じ込められたように感じるのですが、膝をついて座ると目線が低くなり部屋が急に高く感じられます。目線の劇的な変化のない西洋の住宅では、こういった感覚を味わうことはありません。椅子に座った時に目線が一番低くなるくらいですからね。

『聴竹居』において内外の連続性については、どのようなことが考えられているのでしょうか?

内外の関係性のことを考えると普通は窓に着目しますよね。どう開けるかとか、どれくらい大きくするかとか、どれくらい透明なのかとか。本当は外部の構成によって決まるものだと私は考えています。

『聴竹居』の場合、まわりの植栽を気にして見てください。室内から見たときに奥行き感を作る非常に重要な要素となるのです。

庭自体の空間は比較的小さなものかもしれませんが、植物の選び方や配置の順序によって不思議にも奥行き感が生まれているのです。イリュージョンです。ヨーロッパにおけるバロック期の発明にも引けを取らない、内外の特別な関係を創出するデザインです。

日本文化における庭の構成では、時間と空間が強く意識されています。季節の変化による効果を想像しながら植物を選定し、広がりや囲われの感覚を作り出せるのです。私の持っている『聴竹居』の本には、春夏秋冬で異なる景色が映し出されています。冬に雪が降るといつもは暗がりにあるものが目に見えてきますね。雪が黒い枝に積もるときとか。秋にはあらゆるものが赤と黄色の色合いに染まり、夏と春には緑の色合いに染まる。こういった状況が広がりや囲われの感覚にさまざまな影響を与えるのです。

『聴竹居』が1920年代の建築産業に与えた影響はどういったものだったのでしょうか?

色々な点で大きな影響力があったと思います。日本で非常に普及している規格化住宅の雛形を作ったのです。組み立て方や機能や空間の割り振り方、それに寸法や動線などを見てみると、それらが藤井厚二のこの住宅に由来していることがわかります。

藤井厚二の直後から多くの建築家が、伝統的要素と西洋的要素を一つの住宅の中に融合するという課題に取り組むようになりました。例えば、堀口捨己はオランダでデ・ステイルを学んだ後、1933年に『岡田邸』を建てました。モダニズムの白い箱に伝統的な日本の屋根が乗っかっている建物です。

もう一人の建築家 - 前川國男はル・コルビュジエのもとで働き、その思想を日本へ持ち帰ってきた建築家です。それにアントニン・レーモンドのおかげでフランク・ロイド・ライトの影響が日本では根強いですね。彼はアメリカでライトのもとで働いた後、日本にやってきた建築家です。

1920年代の建築家たちは、鉄筋コンクリートといった新しい素材や家具にみられる新しい生活様式を取り入れ、日本の伝統と融合させる実験を繰り返していました。1920年は極めて重要な年です。東京大学の学生たちが、国の保守性や西洋の様式を優先する態度からの解放宣言を掲げて展覧会の開催を発案したのです。彼らは日本のアイデンティティを貶めることなく、自由な創作や彼らの生きる時代の表現を求めたのです。『聴竹居』は1928年に竣工しました。それは学生たちの宣言 - 常に変化と進化を続ける近代世界の中でいかにして日本人の精神を保つのか、という思いの投影されたものでした。

私の東京大学での博士論文は、明治時代から伊東豊雄に至るまでの学生の卒業制作をドキュメントとしてアーカイブ化したものでした。それらを通して、素材や建設技術、社会的習慣の変遷を追うことができました。そして何よりこうした変化をもたらす元となった認知や影響を理解することができました。

この住宅における環境へのこだわりはどこに表れていますか?

藤井厚二博士は、京都大学の環境システム学の教授でした。『聴竹居』は空気の流れをコントロールすることでいかに健康的な住空間を作れるかという実験だったのです。

個々の空間の機能が明確化されているのもそのためです。素材の使い方や地形との関係も示唆的です。『Cho-chiku-kyo』は漢字で書くと『聴竹居』ですから、聴く、竹、住まい、という意味があるのです。

敷地の傾斜を見ていただくと、空気がどこを流れ、その流れが冬と夏とではどう変化するのかが想像できると思います。それに応じて適切に家を換気できるのです。日本の古い家屋を見るとかなり閉鎖的であることがわかると思います。特に冬場は湿気と風通しの悪さで、むっとして息の詰まるほどです。京都の古い町屋は夏をもって旨とすべし、と言われているように全てをオープンにすれば問題なく換気することができるのですが、冬にはそう簡単にいきません。それに京都は山に囲まれているので、家の中の空気は熱がこもってしまい健康なものとは言えません。藤井厚二のイノベーションはこうした問題の解決を目指したものでした。

サスティナビリティのためのモデルとして『聴竹居』は何を提示しているのでしょうか?

今では誰もがテクノロジーに夢中で、それ自体が間違っているとは思いません。ですが、まずは人間としての私たちを理解し環境に対してどう応えていくべきかを考えるべきだと思います。私たちは常々、消費ゼロ、廃棄ゼロ、排出ゼロ、と言っているわけですが、目標を設定して達成への道のりを定めることは難しくないはずです。

大事なのは、こうした統計や戦略よりも私たちが人間であることを忘れないことだと思います。つまり建築家としての私たちが、文化と密接な関係を持たなくてはいけない。サスティナビリティは、私たち自身の振る舞いを認識することによってのみ可能なものなのでしょう。

藤井厚二の孫(小西信一)の回想録を読むと、彼が『聴竹居』の台所にいたときの記憶が描かれています。そこで彼は、建築に導かれるようにして行っていたある振る舞い、つまり、生ゴミを収集し庭の肥料にすることがいかに効率的であったかを思い出すのです。なんてことはない方法で、建築は異なる視点から日常生活への実践を示唆してくれるものです。

日本では、庭や小道を歩いていると道の真ん中に縄でくくられた石が置かれているのを見ることがあります。これ以上先に進んではいけないというサインです。日本人の振る舞いに特有なこうした小さなサインはたくさんありますし、私たちの文化に刻み込まれているものなのです。こうしたシンプルで穏やかなサインは、環境にとって良い行いを私たちに導いてくれるはずなのです。

数字や統計の話ばかりするよりも、こうしたソフト面での対策の方が可能性があるのではないでしょうか。『聴竹居』が有名になったのは、技術的に高度な解決策を提示したことに加えて、藤井厚二がそのことを文章で強調していたからです。ですが、それよりもサスティナブルという観点で重要な特質がこの住宅にはあるのだと思います。要するに、周辺環境の質、伝統的な振る舞いへの敬意、そして抑制された好奇心に育まれた控えめなイノベーション、ということでしょうか。

『聴竹居』は広い視野をもった事例と言えるでしょう。それ自体が興味深い住宅でありながら、環境との関係を保持している。つまり丹下健三と同じように、建築を扱うことは、ただのオブジェクトとしてではなく、あらゆるスケールを横断し都市との関わりを持つことなのだ、ということに藤井厚二も意識的であったのです。

今日の議題は、様式からサスティナビリティへと変わっていったということですが、様式の問題は解決されたのでしょうか?

人々はオーセンティックなものを求めているようです。気候非常事態によって、抽象的な問題を議論するよりも、私たち自身を見つめ直し、私たちの立ち位置を模索する必要が出てきたのです。私たちの周りには複雑なことが起こっていますし、その中で形の議論に対する比重が下降傾向にあるのはお分かりでしょう。もちろん議題の一つとして残るとは思いますが、より広域な環境にとって、それがどれほど貢献的なものなのかはわかりませんね。

2021年11月06日

Erwin Viray: I have chosen to speak about Chochikukyo for two reasons.

Firstly, it seems to be one of the earliest houses to address, through environmental engineering, the issue of sustainability, which, as we are all aware of, is currently one of the most discussed international topics.

Secondly, I was always very attracted by its transitory character. As a house it's a testimony to a period of dynamic change within Japanese society. Its architecture has both Japanese and Western features. The architect - Koji Fujii was a pioneer in the use of the metric measurement system, which challenged the traditional Japanese Tatami language of spatial planning in residential buildings. Only because of this, the house already feels very different from typical Japanese structures. Nevertheless, its overall character stems directly from the local sensibility and has a lot in common with Sukiya style (1574-1867) architecture - which was partly present in elegant wooden tea ceremony pavilions.

WHAT WERE THE WESTERN AND JAPANESE FEATURES THAT KOJI FUJII MIXED IN CHOCHIKUKYO?

The first two decades of the 20th century in Japan were a period of vivid discussion on the appropriate style, materiality (wood or bricks) and inclusion of western influences in everyday culture. At the time, European techniques and aesthetics were becoming ever more present in the Japanese architectural debate.

As such, protecting Japan-ness, i.e., the specificity and national character of Japanese architecture, while adapting it to the new conditions, became an important counter topic. Before Chochikukyo was built, the example was set by Japanese nobility, who, when erecting new official palaces, built them in pairs; a Japanese wooden, traditional house and a Western brick version next to it.

The Western building served as a sort of fashionable pavilion for exotic activities like sitting at a table with chairs etc., an acknowledgement of the novel developments of another culture but at the same time a failure to re-understand or evolve the national way of life. It was therefore surprising, and innovative, that Koji Fujii combined these two „styles” in one house.

This intention is immediately visible from the exterior of the building - windows wrap around the corners, a well-known modernistic feature, and upon entering, you see electric lighting, directly inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, who was building the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo at that time. Also noticeable, is the curved wall opening between the dining room and the living room - a quotation, and something that had not been done in Japan before.

Moreover, the rooms have a specific function, related to the furniture they contain and their location in the house. Spaces were not defined by the laying of mats, but by western measurements that are at once precise but then also abstract to the dimensions of people and cultural movements in space.

I recently skimmed through the book The English House (1904) by Herman Muthesius and realised that the layout of Chochikukyo could have been inspired by Muthesius’ writing. As far as I know the publication circulated among architects in Japan during the 20’s.

It’s a meticulous work, analysing the qualities of dwellings in which the author describes each specific space of a house as a separate entity. For example, in Chochikukyo the bedrooms are clearly defined in a separate part of the house – which would have been a very avant-guard or ‘European’ decision.

HOW ARE THE INDIVIDUAL ROOMS DEFINED? COULDN’T YOU CHANGE THE FUNCTIONS ACCORDING TO YOUR PREFERENCES?

Usually in Japanese houses, bedrooms and the dining room are not that much different. A living room can be a dining room, can be a bedroom etc. In Chochikukyo you could theoretically swop the living with the dining room, they are both part of one main space, however, as far as I am concerned, the functions are meant to be where they are. It was very much a Loos’ian way of thinking about domestic space. The public and the private areas are distinguished in their character, grade of opening and access. I think, it was a feature that pushed Chochikukyo even further from the Japanese orthodoxy.

WHAT TYPICAL JAPANESE ELEMENTS REMAIN IN THE BUILDING?

For instance, the preference to have rather dim light. As you might know from the book In Praise of Shadows (1977) by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, in the Japanese context, the spaces between lightness and darkness are traditionally perceived as attractive. Chochikukyo is not a white box soaked with light, as the modern dogma might have prompted, it is instead darker, with Koji Fujii using materials that recalled the interiors of traditional Machiyas. The way of using the thresholds between spaces is also deeply rooted in the ceremonial way of receiving guests in Japan.

WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY CEREMONIAL WAY OF RECEIVING GUESTS?

In Japan, there is always a hierarchy or sequence which determines how activities and levels of intimacy are controlled. It’s better to make a room suitable for a diverse spectrum of activities and as such, you would avoid creating thresholds that require guests to receive invitations or directions to enter. The central space in Chochikukyo is a formal space for receiving guests, but it also allows circulation if the adjacent spaces are occupied by other activities.

This so-called living room enables the gradation of involvement of spaces in the common life of the house. Thanks to it, you can be aware of what happens in each room, whilst maintaining your autonomy and the privacy of the place you are in. The compartmentalisation of the activities and the spaces enables a subtle mediation of in-between situations. You never intrude either physically or acoustically into a space before being allowed to do so. It’s a very strong characteristic of Japanese social norms.

IN A WESTERN CONTEXT, IT IS PROBABLY NOT VERY CLEAR HOW A TEA HOUSE IS USED. HOW DOES IT WORK?

In the case of the house we discuss, the teahouse is not in the house itself. There is a smaller pavilion behind the house. It has the proper components of a teahouse - there is a pathway to reach it and the necessary devices to purify yourself before entering. The entrance is small. Inside you see Tatami mats, the tokonoma, the place of honour, and the place where the host prepares the tea. The seating is arranged based on who is the guest. A tea ceremony is an elaborate way of celebrating the presence of guests, peacefully distant from everyday activities, and relative to the ever-present beauty of nature.

DOES THE SPACE BUILT ACCORDING TO THE JAPANESE TATAMI SYSTEM SEEM BIGGER, OR SMALLER THAN IT REALLY IS?

It is difficult to answer directly, the effect of the house is result of a combination of western measurements and eastern atmospheric conditions. Chochikukyo seems to be bigger and higher, probably because of the metric system it follows. For instance, ceiling height, in Japanese space is usually quite low, and is a character that Frank Lloyd Wright equally captured and adopted successfully in some of his buildings. If you go to visit the houses he built in Japan or to some of his houses in the US, you immediately see that the ceiling is low, and the eaves are longer than you would expect. The quality of light inside becomes very subdued, the environment is never particularly bright. It is very different from the works by Mies for instance. In the Farnsworth house light penetrates the plan fully and at worst, you experience even glare.

I remember a lesson that one Sukiya carpenter gave me. Namely, that the level of the eye is very important. The Tea room for example, is usually a small space and when you enter, standing, it feels very confined, very claustrophobic. But when you kneel and sit down your eye level is very low, and the room suddenly feels much higher. You rarely have this feeling in Western houses which are not usually designed around radical changes in viewpoint; the lowest level you reach is when you sit down on a chair.

HOW DOES CHOCHIKUKYO DEAL WITH THE CONTINUITY BETWEEN INSIDE AND OUTSIDE?

Usually when we speak about the relationship between inside and outside in a house we tend to concentrate on windows, the way they open, how big, or transparent they are and so on. However, as far as I am concerned, the right effect is often very much bound to the composition of what is outside.

In case of Chochikukyo one should look at how the vegetation is coordinated around the house. Its effect is extremely important on how a sense of depth is created when looking from inside.

The space of the garden might be relatively small, but because of the plants, the species that were selected and the way they have been placed behind each other, a magical depth is created. An illusion. Comparable to the experiments of the Baroque period in Europe, the design produces a special relationship between the inside and outside.

In Japanese culture, the composition of the garden is strongly orientated to time and space. You create a widening or an enclosure and within it; you choose the plants carefully to perform certain effects in different seasons. I have a book on Chochikukyo, that shows the differences of views you have in summer, spring, autumn and winter. You can see that in the winter when the snow falls, what normally is dark becomes luminous, you have the snow on the black branches. In autumn, everything is in different shades of red and yellow. In summer and spring, you have instead diverse shades of green. Each of these situations has a different impact on your feeling of continuity or enclosure.

WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF CHOCHIKUKYO ON THE ARCHITECTURAL PRODUCTION IN THE 1920’S?

It became very influential in many ways. It created a template for prefabricated modular houses, that are today still very popular in Japan. When you look at how they are assembled and how they define functions and spaces, measurements and circulation, a lot comes from this house by Koji Fujii.

Shortly after Koji Fujii, many architects started to work on the task of melding both traditional and western elements in to one house.

For instance, Sutemi Horiguchi went to Holland and studied De Stijl before going on to build the Okada House in 1933, which was a combination of a modernist white box with the windows and roof taken from a traditional Minka.

Another architect - Kunio Maekawa, worked with Le Corbusier and brought his ideas home. You could find a very strong influence of Frank Lloyd Wright brought over to Japan by Antonin Raymond. He went to work with FLW in the USA and eventually ended up in Japan.

During the 1920s these architects were experimenting a lot, introducing new materials like reinforced concrete, new concepts of living, like furniture, and mixing them with Japanese traditions. 1920 was a pivotal year. A group of students from the University of Tokyo decided to make an exhibition declaring freedom from the conservatism, but also from dominance of Western styles of architecture. They intended to create something free and expressive of the age they lived in, whilst not discrediting Japanese identity. Chochikukyo was built in 1928. It reflected the student’s declaration - a reflection of how to keep the Japanese spirit in an ever changing and evolving modern world.

For my PhD dissertation at the University of Tokyo, I documented and created an archive of student graduation works from Meiji period all the way up to Toyo Ito. Through this I could observe the transformation in materials, construction techniques, social customs and importantly, the perceptions and the influences that gave rise to these changes.

HOW ARE ENVIRONMENTAL PREOCCUPATIONS EXPRESSED IN THE HOUSE?

Dr Koji Fujii was a professor of environmental systems at the University in Kyoto. Chochikukyo became an experiment centered on how you can create healthy domestic spaces, through the management of airflow.

This preoccupation clearly defined the function of individual spaces. It also had implications on the materials used, and the relationship of the house to the terrain. Chochikukyo, written in Chinese characters 聴竹居means: “listen, bamboo, dwelling.”

There’s a certain slope, looking at it, you can imagine where the air would flow and how this would change during the winter and summer, ventilating the house accordingly and properly. If you look at some of older houses in Japan, they are quite closed, and can be stuffy due to humidity and lack of airflow, especially in winter. The old Machiyas in Kyoto are designed for summer, as people say, because you can open everything and ventilate perfectly, in the winter it was not so easy. Moreover, Kyoto, surrounded by mountains, retains a lot of heat, and the air quality in the houses was never as healthy as one would have wished it to be. Koji Fujii’s innovations were aimed at addressing these issues.

WHAT MODEL OF SUSTAINABILITY DOES CHOCHIKUKYO PROPOSE?

Now everybody is fascinated with technology, and it’s not wrong per se, I just think that first we should understand ourselves, as human beings, and the ways in which we react to the environment around us. We speak all the time about zero consumption, zero waste, zero emission. It’s clear we can set targets and determine ways of achieving them.

However, what I think is important, above all these calculations and strategies, is not to forget the human being. That means, as architects, we need to operate in tight connection with culture. Sustainability is only possible if we acknowledge it in our own behavior.

Reading through the recollections of Koji Fujii’s grandchild (Konishi Shinichi) you encounter memories of being in the kitchen at Chochikukyo, where he was guided by architecture to behave in a certain way.

He would remember how it was very efficient for them to collect the organic waste, and later use it to fertilise the garden. In a very subtle way, architecture can somehow guide you through everyday life and make you practice things differently or perhaps in a better light.

Often in Japan, when you’re in a garden or on a pathway you will find, placed carefully in the middle, a stone with a rope on it. Usually, this sign means that you are not to go further. There are many little signals like this that are inherent in Japanese behaviour, engrained in our culture. In my mind, simple calm signs such as these, could be useful in guiding people to do certain things that are better for the environment.

I see this kind of soft strategy potentially more successful than talking only about numbers and statistics. Chochikukyo became famous because of its technically advanced solutions and the emphasis Koji Fuji put on them through his writing. However, I think there are more important qualities within the house, that make it sustainable. Namely, the qualities of the environment around, the respect towards patterns of traditional behaviour, discreet innovations that nourished curiosity without overwhelming it.

Chochikukyo is an example of a broader vision. Not only is the house interesting itself, but it has a relationship to its environment. Similarly, to Kenzo Tange, Koji Fuji was aware that when you deal with architecture, it’s not just about an object. It crosses all scales and deals with the city.

WE HAVE PASSED THROUGH AN EPOCH OF DISCUSSION ABOUT STYLE AND ARRIVED AT THE POINT OF SUSTAINABILITY. ARE WE DONE WITH STYLISTIC ISSUES?

People seem to be looking for authenticity. Because of the climate emergency there is a need to look at ourselves and investigate where we’re standing, rather than discussing about abstract issues. There are complex things happening around us. And we can observe that the topic of form slides down the hierarchy of importance. It will of course remain part of the discussion, but it will be questioned to what extent it supports the quality of the much wider environment.

06.11.2021

埃尔文-维雷 我选择谈论听竹居有两个原因。

首先,它似乎是最早通过环境工程解决可持续性问题的住宅之一,正如我们所知,可持续发展是目前讨论最多的国际性话题之一。

其次,我一直被它的过渡性特质所吸引。作为一栋住宅,它见证了日本社会的一个动态变化时期。

它的建筑同时具有日本和西方的特点。建筑师藤井厚二是使用公制测量系统的先驱,这对日本传统的住宅建筑空间规划上使用的榻榻米度量构成了挑战。仅仅因为这一点,已经能感受到这所住宅与典型的日本结构有着很大的不同。然而,它的整体特征直接源于当地的感觉,与数寄屋风格(1574-1867)的建筑有很多共同之处——这部分的呈现于优雅的木制茶室中。

藤井厚二在听竹居中混合了哪些西方和日本的特点?

20世纪头20年的日本,活跃着关于合适的风格、材料(木头或砖)和在日常文化中纳入西方影响的讨论。当时,欧洲的技术和美学越来越多地出现在日本的建筑讨论中。

因此,保护日本性,即日本建筑的特殊性和民族性,同时使其适应新的条件,成为一个重要的对立话题。在听竹居建成之前,日本贵族树立了榜样,他们在建造新的官方宫殿时,都是成对建造的;一座日本的木制传统住宅和旁边的西方砖制住宅。

西方的建筑作为一种用于异国情调活动的时尚的场馆,如坐在有椅子的桌子前等,这是对另一种文化新发展的承认,但同时也是对民族生活方式的重新理解或发展的失败。因此,藤井厚二将这两种 "风格 "结合在一栋住宅中是令人惊讶的,也是创新的。

这种意图从建筑的外部就可以看出来——窗户环绕着角落,这是一个著名的现代主义特征,一进门就可以看到电灯,直接受到弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的启发,他当时正在东京建造帝国酒店。同样值得注意的是,餐厅和起居室之间的弧形墙体开口——这是一种引用,也是以前在日本没有做过的事情。

此外,房间的规划具有非常具体的功能。卧室在住宅的一个独立部分(删除并移至下一段)。房间有特定的功能,与其中的家具和房间在住宅中的位置有关。空间不是由铺设榻榻米来定义的,而是由西方的测量方式,这些测量方式一方面精确,一方面对于人和文化活动在空间中的尺度是抽象的。

我最近浏览了赫尔曼-穆特修斯(Herman Muthesius)的《英国人的住宅》(1904)一书,意识到听竹居的布局可能是受到穆特修斯的启发。据我所知,该出版物在20年代的日本建筑师中流传。

这是一部细致的作品,分析了住宅的品质,其中作者将住宅的每个具体空间都描述为一个独立的实体。例如,藤井厚二的卧室被明确定义为住宅的一个独立部分——这本来是一个非常前卫或 "欧洲 "的决定。

每个房间是如何定义的?你不能根据自己的喜好来改变功能吗?