ミカエル・オルソン:2000年頃のことです。フロサクルにある、ブルーノ・マットソンが1960年にデザインしたサマーハウスに行くことができました。到着して中に入ると、そこが何年も手つかずであったことに気づきました。オリジナルの家具やオブジェ、カトラリー、それにマットソンの私物がたくさん残っていました。家は劣化していました。壁にはカビが生えていましたし、繊維強化プラスチックの屋根は、黄味がかってきていました。ところが、家が自然へと還り始めてもなお、その優美で自然体な姿は、残されていました。

最初は、引力と反力の入り混じった感覚を感じました。この感覚は何なのか、居ても立っても居られなくなり、この家の鍵を借りて、撮影プロジェクトを始めても良いか、とオーナーに聞いてみることにしたのです。撮影を終えるには、ここにもっと長くいるべきだと感じたのです。この建物がどう変化するのか、それに何が私を惹きつけているのか知る必要があると思ったのです。

鍵を手に入れることができ、私は何年もの間、いつでもそこへ行くことができました。その間、この家を使う人は、本当に誰もいませんでした。私は、一人でいることはあっても、他に誰かを呼ぶことはありませんでした。それは、芸術的探求のための場所でした。夏の間は、長く滞在することができました。冬や春は、とても寒かったですね。外が寒い日は、中はもっと寒かったくらいです。私の写真のイメージからも、そのことがわかると思います。部屋の中のバケツの水が、固く凍っています。3月の始めのことですよ。

この家は、マットソンの住まいに対する考えが示された実寸大のテストなのです。動く壁や、タイヤのついたストーブ。本当に、中でも外でも料理ができますよ。それに、マットソンは、外で寝るときもありました。昼間は、家の中から外を観察すると、ガラスや波板プラスチックの壁越しに、自然が見えてきます。

自然は、物事の現象が投影された景色となっています。風が木々を揺らすのがわかるでしょう。夜間は、それとは逆のことが起きます。この家が、通り過ぎる人々にとっての景色となるのです。自然は、暗闇のなかへ消え、動くシルエットが現れてきます。シルエットは、リビングルームでは、くっきりと明瞭に。そして中庭では、ぼんやりと。中庭側のプラスチックパネルが、シルエットの形を歪め、輪郭を柔らかくしているのです。

私は、写真家、そしてアーティストとして、この家に関わってきました。画家が自分のスタジオに行くのと同じように。その内部へと飛び込み、イメージメイキングの奥深さや可能性を探っていきました。次のような問いが私を導いてくれました。

二次元のイメージの中に、建築はいかにして表現され得るのだろうか?写真とは何なのだろうか?

ただ、実験をしてみたかったのです。

実験とは、どういったものだったのでしょうか?

最初、私はかなり警戒していました。全てを元あった姿に戻す前に、さまざまな「セッティング」をして、サクッとポラロイドで撮影しました。どういうわけか、誰かがここへ戻ってきて、私がここで何をしていたのか、チェックするのではないかと思ってしまったのです。ですが、しばらくすると、家にいるようにくつろげるようになって、リラックスできるようになりました。料理もするほどに。マットソンのカトラリーでね。

何年にもわたって、この家に秘められたポテンシャルを明らかにしようと、繰り返し空間をアレンジし直しました。見かけ上の空間の構成を崩し、その先にあるものを見るために。ひたすらテストをしていました。イメージを組み立て、写真を撮り、印刷し、の繰り返しでした。

この家は、テストベッドになっていたのです。天井の一部をも取り払い、空間の新しい可能性を広げようとも試みました。私の作品集「Södrakull Frösakull」には、いくつかの異なる部屋が写されています。これらのイメージは、ひとつのシリーズになっていて、この家を、実際よりも大きな空間に感じさせています。平面図を見ると、小さい家だということがわかると思います。外部のパティオを含んでも、せいぜい10m×15mくらいのものです。

私にとっては、ここでの経験全てが、建築のイメージとは何なのか、何になり得るのか、といった問いを投げかける絶好の機会でした。見る人の視線をひきつけるイメージを作るには、建物やインテリアがどう役立つものなのか、が実験できたのです。

フロサクルで実験を行う中で、あなたの作品はどう進化したのでしょうか?

このプロジェクトの間、空間の見せ方や表象に対する、さまざまな表現方法を探求することができました。それで今では、コミッションワークと自分自身のアートワークとの間を、簡単に行き来できるようになったのです。さまざまな表現方法やアイデアをどう扱うか、ということです。つまり、クライアントの美的な好みと調和する表現のモードから、私の美的な好みを優先した個人的な取り組みのモードへと切り替える方法が、今ではわかるのです。

私の作品は、常にイメージを扱っています。それに歴史と写真。コミッションワークは、アーティストとしては行いません。ですが、アーティストとしての知識を活かしながら、イメージの形成という点においては、クライアントの作品を強化することできます。

当初は、あの家に行って写真を撮るだけでした。ところが、しばらくたって、私が本当に見たものは、何だったのか確かめるために、気持ちを入れ替える必要を感じました。4×5のアナログカメラを使うのが好きなのですが、そうすると作業が非常にゆっくりになるのです。すると、気持ちもゆったりとしてきます。カメラの前に、何が現れているのかを考え始めるようになり、集中できるのです。こういったことの全てが、何年も心に刻まれるような観測を導いてくれるのだと思います。

知覚における一般的な問題は、それがすぐに不注意で表面的なものになってしまうことです。枠の外側に目を向けるよう、自分を律する必要があるのです。「木を見ていては、森は見え」ません。幾度となく木を見ていると、遂には、認識すらしなくなるものです。私はよく自分自身に、再スタートするように言い聞かせています。目の前にあるものが、初めてそこにあるかのように知覚するためです。

あなたの作品集「Södrakull Frösakull」では、二つの家で二つの撮影方法が試みられていますね。

そうです。もう一つの家は、ソドラクルにあるマットソンの日常生活の家です。私が訪れたときには、誰も住んでいませんでした。荒廃していて中に入ることもできませんでした。それで私は周囲を歩いて、のぞき見るようにして撮影したのです。

廃屋を見つけると、中がどうなっているのか気になってしまう感覚は、誰しもが持つものだと思います。あなたは、家へと近づいていき、あなたの目が家の中へと浸透していく。この瞬間を写真で伝えたかったのです。これらの写真は、本の最初の方に載せています。抽象的なイメージとして。

見捨てられたサマーハウスからは、同じく見捨てられた彼の家よりも、さらに深い悲しみのようなものが喚起されたのでしょうか?

状況は、変化するものです。私の写真に対する考え方は、全くノスタルジックなものではありません。マットソンの家からは、ある種のノスタルジアが感じられるかもしれません。ですが、むしろそこには、現代のスウェーデン社会に深く根差した考えが、極度に集中した形で表れています。マットソンは影響力のあるデザイナーでした。彼のプロジェクトからは、彼の考えや好みが、はっきりとわかります。彼は、自然主義的で、健康や明るさ、それに空気や太陽といったものに、非常に強い興味をもっていました。

マットソンは、アメリカに行き、MoMAのキュレーターであるエドガー・カウフマンと会っています。彼は、アメリカ建築界で紹介され、ミース・ファンデル・ローエや彼のクライアントであったミセス・ファンズワースに会っています。彼女は、マットソンの家具を購入していましたし、ファンズワース邸のオリジナル写真に映っているのは、まさに彼の家具なのです。チャールズ&レイ・イームズには、ロサンゼルスの彼らの家が、建設中のときに会っています。

1950年代にプラスチックで家を建設するということは、家がずっとそこにあるわけでないことを意味しています。石の家であれば、何世紀にもわたって存在するでしょうけれども。ペーパーハウスはDNA的にも脆いものですし、消えてしまうものです。そういったものを、一時的な存在として受容することは、楽しいことなのだと思います。とても気楽なものですし。だから私は、フロサクルのサマーハウスが好きなんだと思います。家とは一体何なのか、といった問いを投げかけてくれるのです。そういった中では、慣習にとらわれずに行動するものです。決まり切ったことなど、やらなくなる。未定義でオープンな性質が、いろんな事をやってみようという気にさせてくれるのだと思います。予期せぬ創造が生まれ、それに魅了される。そういったことが、健康にも、心にとっても良いことだと気づきました。

サマーハウスには中心がありません。セントラルヒーティングもありません。つまりどこから暖かくなるのか、あるいはどこで終わるのかが曖昧です。この家は、どこにでもあるし、どこにもない、という感覚でしょうか。この家は、あなたに簡単についてきてくれるものでもないですし、理解しやすいものでもない。慰めてもくれない。こういった点で、フロサクルの家は、とても興味深く、普遍的なものだと思うのです。悲しみやノスタルジーといったものよりもね。

マットソンのデザインした他の家にも、ほとんど行きました。彼の作品や考えをより理解できるだろうと思ったからです。(スウェーデンの町コスタにある、彼のデザインした長屋の映像も撮りました。)オリジナルの椅子を自慢してくれるオーナーや、50年代のジャケットを来ているオーナーに会ったりもしました。過去や、良かった時代の記憶、それに恣意的な感情、といったものにコントロールされるのが好きな人もいるのですよね。驚きました。

私は、作品からあらゆるセンチメントを排除しようとしているのです。モチーフがセンチメンタルなものであっても、それをメッセージとして伝えるようなことはしたくない。とても危険だと思います。

家は、もう売却されてしまいましたし、そこにはもう行けないのですよね?

そうですね。良かったです。まだ鍵を持っていたら、またそこに行って、写真を撮ってしまう。いつかは辞めたかったのです。ある時、オーナーが私に、その家を買わないかとさえ言ってきました!

断りましたよ。購入していたら、私はその家の囚人となっていたでしょう。本当にとりつかれていましたから。

何にとりつかれていたのですか?

面白いイメージを作ることに、です。

今は、どういった考えで作品を作っているのでしょうか?

対象への知覚と、対象そのものの違いについて、です。

私の作品では、対象それ自体が重要なわけではなく、その対象が生み出す知覚的実験の方が重要です。ところが、イメージは常に何らかの描写であって、そこから逃れることはできません。アナログフィルムで撮った写真は、あなたの目の前に映る世界のレリーフです。技術的な複製ではありますが。それでも、カメラはマシーンではないのです。 装置なのです。私は、様々なレンズを用いながら、私の知覚と表現に対する考えを明瞭にしていくのです。撮る対象がなんであれ関係ありません。

素材や、対象や、モチーフ。そういった対象が問題なのではなく、どのようなアプローチでそれを明瞭にしていくか、なのです。建築家、あるいはアーティストとして、このことを理解できるようになると、物事の見方も変わると思います。ドキュメンタリー作家であれば、そこにあるものが重要です。ただ、あなたがアーティストや、イメージメーカーなのであれば、事実とイマジネーションとを組み合わせる事が重要です。ヘルツォーク&ド・ムーロンとアイ・ウェイウェイのサーペンタイン・ギャラリーを撮影した本「on | auf」でピーター・ナダスが、そのことを指摘してくれました。私の仕事はいわば、建物を借りた「自律的空間」の創造なのだと。

知覚、転置、境界の空間。こういったテーマをもっと探求していきたいですね。とりわけ、シーグルド・レヴェレンツのプロジェクトにおいては。かれこれ、2000年から取り組んできているプロジェクトですから。

2022年11月5日

Mikael Olsson: Around 2000, I got access to Bruno Mathsson’s summer house in Frösakull, which he designed in 1960. I arrived, entered and realised that it had been untouched for years. It was full of original furniture and objects, including cutlery and Mathsson’s personal belongings. Parts of the house were degraded; fungus grew on walls, the fibre reinforced plastic roof had become yellowish. Despite nature starting to reclaim the house, its elegance and naturalness remained.

Initially, I felt a mix of attraction and repulsion. I couldn’t stop thinking about what this feeling meant. I decided to ask the owners if I could have the keys to the house and initiate a photographic project about it. To finish the work, I felt that I needed to stay there longer, I needed to explore how the building was changing and what effect it was having on me.

I got the keys, and for many years, I went there whenever I wanted. Nobody was really using the house during this time. I was there by myself and did not invite other people. It was a place of artistic exploration. During the summer I went there for longer periods. In the winter or spring, it got very cold; when it was cold outside, it was even colder inside. You can sense this in some of my images. Inside, there were buckets of water, frozen solid, even in the beginning of May.

The house is a full-scale test of Mathsson’s ideas on how to dwell. Movable walls, a stove on wheels. You could actually cook both inside and outside. And Mathsson himself sometimes even slept outside. When looking out from the house during the daytime, you see nature either through glass or corrugated plastic walls.

Nature becomes a scene where things happen. You observe it and can see how the wind moves the trees. In the evening, the opposite is true. The house is a scene to the people passing by. Nature disappears into darkness and moving silhouettes emerge. They are sharp and explicit in the living room and blurred in the courtyard, because of how the plastic panels distort the shapes and soften the contours.

As a photographer, an artist, I treated the house as a painter going to his studio. I went there to dive in and explore the depths and possibilities of image making. The questions that guided me were:

How can architecture be represented in a two-dimensional image? What is photography? I wanted to experiment.

WHAT WERE THE EXPERIMENTS ABOUT?

In the beginning, I was quite cautious. I arranged different ‘settings’ and took fast Polaroid’s, before putting everything back how it had been. Somehow, I thought that somebody would come back to see how it looked, to check what I was up to. But after a while I felt quite at home in the house and became more relaxed. I even started cooking there, using Mathsson’s cutlery.

Over the years, I rearranged the space many times to uncover its hidden potential; to deconstruct and see beyond its obvious spatial organisation. I was just testing. Composing images, taking photographs, printing.

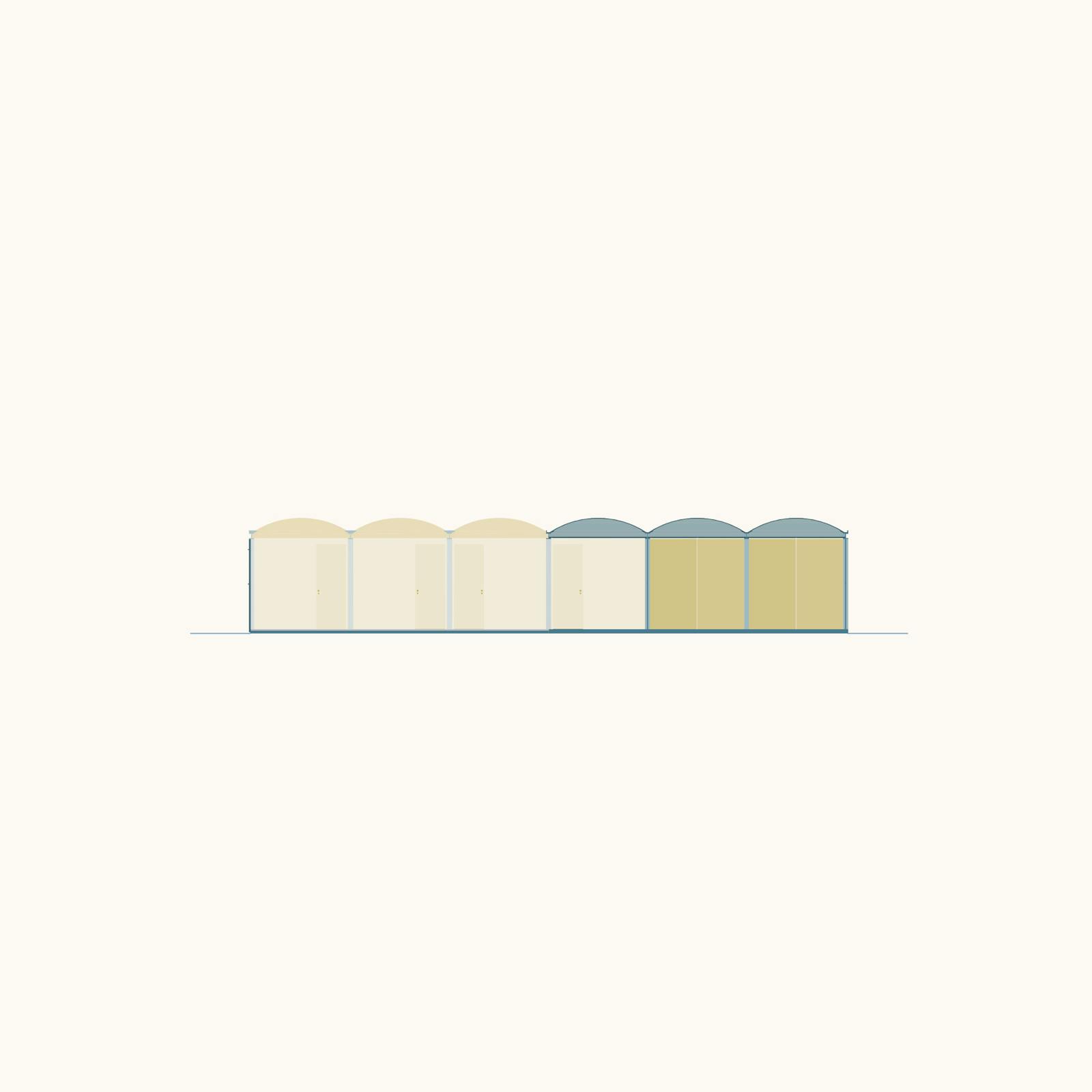

The house became a testbed. I even took parts of the ceiling down to unfold new spatial possibilities. In my book Södrakull Frösakull several different rooms are present. These images are fused into a series which gives the impression of the house as a much larger space than it is. Looking at the floor plan, you realise that it’s a small house – around 10 x 15 meters, including the external patio.

For me the whole experience was a perfect opportunity to question the idea of what an image of architecture was, or what it could be. I was experimenting with how the building and its interior could help me create images that would attract the gaze of a viewer.

HOW DID YOUR OWN WORK EVOLVE DURING THE EXPERIMENTS AT FRÖSAKULL?

During the project I explored different ways of representation, of how to show and represent space. That’s why I can now easily shift back and forth between commissions and my own artistic projects. It’s about handling different kinds of representations and ideas – and now I know how to switch from a representation mode which harmonises with my client’s, aesthetics preferences to the one that engages me personally.

My own work always deals with image, history and photography. When I do commissions, I am not an artist. But I use my artistic knowledge to strengthen the work of the client in the form of an image.

At the start, I just went to the house and photographed. But after a while, I had to restart my mind to see what I actually saw. I like to use a 4 x 5 analogue camera and with this you work really slowly. Your mind slows down. You start thinking about what appears in front of the camera. You are concentrated. All this leads to observations that remain in your mind for years.

A common problem of perception is that it quickly becomes mindless and superficial. You need to discipline yourself to look outside the box. „You can’t see the forest for the trees”. You’ve seen a tree so many times, that you eventually stop perceiving it. I often tell myself to restart – to allow my mind to perceive what is in front of it, as if it were there for the first time.

YOUR BOOK SÖDRAKULL FRÖSAKULL SHOWS TWO DIFFERENT HOUSES AND DIFFERENT WAYS OF APPROACHING THEM.

Yes, the other house, in Södrakull, was Mathsson’s full time residence. When I first visited it, nobody lived there. It was in disrepair, and I didn’t have access. I walked around and took Peeping Tom images.

I guess everybody recognises the feeling of finding an abandoned house and being interested in how it looks inside. You go close, and with your eyes you try to penetrate the interior. I wanted to translate this moment into photographs. Those pictures became the beginning of the book – the more abstract images.

DO YOU THINK THE ABANDONED SUMMER HOUSE PROVOKES A DEEPER FEELING OF SADNESS THAN THE ABANDONED RESIDENCE?

Things are changing. My idea of photography is not at all nostalgic. Even if Mathsson’s house represents some kind of nostalgia, it also represents, in an extreme and concentrated way, ideas that are deeply rooted in the modern Swedish society. Mathsson was an important designer. He had ideas and preferences that clearly found expression in his projects. He was very interested in naturism, fitness, lightness, air, sun.

Mathsson went to the USA. He met Edgar Kaufmann, a curator at MoMA. He was introduced to the American architectural scene. He met Mies van der Rohe’s client Mrs. Farnsworth. She even bought Mathsson’s furniture, and it is his furniture that we see in the original photographs of the Farnsworth House. He visited Charles and Ray Eames during the construction of their house in Los Angeles.

When building with 1950’s plastic elements, the house is not meant to be there forever. A stone house, on the other hand, can stand for centuries. A paper house has fragility in its DNA. It will disappear. To accept the condition of temporary existence is interesting, I think. It’s very relaxing. I guess that it is what I like about the summer house in Frösakull. It forces you to question your idea of what a house is. In such a structure you start to act in a less conventional way. You don’t do the obvious. Its undefined open character invites you to try things out. It creates the unexpected. That’s what attracts me to it. I find it healthy and good for the mind.

The house doesn’t have a center. There is no central heating; the definition of where the warmth begins and where it stops is diffuse. The house is somehow everywhere and nowhere. It’s not a house that comforts you with easy associations and predictability. It is for these reasons, that I find the Frösakull house much more interesting and universal than sad or nostalgic.

I have visited nearly all of Mathsson’s other houses, too. I went to see them because I believed that they would help me to understand his work and ideas better (and I also made a film on his row houses in the Swedish town of Kosta). Sometimes I met owners boasting about original chairs and wearing jackets from the fifties. Some people like being controlled by the past, by memories of better times or arbitrary sentiments. This surprises me.

I try to exclude all sentimentality from my work. Even if the motif is sentimental, I don’t want to herald this as a message. I think it’s dangerous.

AND NOW, DID THE SALE OF THE HOUSE CUT ALL POSSIBILITIES OF GOING THERE?

Yes, and it’s a good thing. If I still had the keys, I would go there and take more pictures. At some point, I wanted to stop. At one point the owners even asked if I wanted to buy the house!

I declined, because if I had bought it, I would have become its prisoner. I was so obsessed by it.

WHAT WERE YOU OBSESSED ABOUT?

How to make interesting images.

WHICH IDEAS ARE YOU WORKING WITH RIGHT NOW?

The difference between the perception of the object and the object itself.

In my work, the object itself is less important than the perceptive experiments it allows. However, an image is always a description in some way. You can’t get away from that. Using analogue film, photography is a relief of the world in front of you. But it’s a technical reproduction. A camera is not a machine. It’s an apparatus. Using different lenses, I articulate my ideas on perception and representation, regardless of the object.

It’s not about the material, it’s not about the object, it’s not about the motif. It’s about how you approach it, how you articulate it. Once you understand this as an architect or an artist it changes the way you look at things. When you work as a documentarist, it’s about what’s there. But when you work as an artist, or as an image maker, it’s a combination of facts and imagination, as the author Péter Nádas notes in on | auf, the book I did on the Serpentine Gallery project by Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei. I, so to speak, borrow the buildings to create an “autonomous space”.

I will explore these themes – perception, displacement, liminal spaces – further in a project on Sigurd Lewerentz, which I have been working on since 2000.

05.11.2022

米卡尔-奥尔森: 2000年左右,我进入了布鲁诺-马特松在弗洛萨库尔的夏季别墅,这是他在1960年设计的。我来到这里,进入后才发现,它已经多年没有被人动过了。那里充满了当初的的家具和物品,包括餐具和马特松的私人物件。住宅的某些部分已经退化了;墙壁上长出了真菌,纤维增强复合材料(FRP)的屋顶已经变黄了。尽管大自然开始回收这所住宅,但它的优雅和自然性仍然存在。

起初,我感觉到一种吸引力和排斥力的混合。我无法停止思考这种感觉意味着什么。我决定问问业主,我是否可以拥有这所住宅的钥匙,并启动一个关于它的摄影项目。为了完成这项工作,我觉得我需要在那里待更长的时间,我需要探索这个建筑是如何变化的,它对我有什么影响。

我拿到了钥匙,许多年来,只要我想,我就会去那里。在这段时间里,没有人真正使用这所住宅。我独自在那儿,没有邀请其他人。那是一个探索艺术的地方。在夏天,我去那里的时间更长。在冬天或春天,它变得非常冷;当外面寒冷,里面更冷。你可以从我的一些图片中感受到这一点。里面有一桶桶的水,冻得很结实,甚至在五月初的时候。

这所住宅是对马特松对居住方式的想法的一次全面测试。可移动的墙壁,带轮子的火炉。你实际上在室内和室外都可以做饭。马特松本人有时甚至睡在外面。白天从住宅里向外看时,你可以通过玻璃或波纹板墙看到大自然。

大自然成为一个事情发生的场景。你观察它,可以看到风如何移动树木。到了晚上,情况就相反了。对路过的人来说,房子是一个场景。大自然消失在黑暗中,移动的剪影出现了。它们在客厅里是清晰的,在院子里是模糊的,因为塑料板扭曲了形状,软化了轮廓。

作为一个摄影师,一个艺术家,我对待这所住宅就像一个画家去他的工作室。我去那里是为了潜入并探索图像制作的深度和可能性。引导我的问题是: 建筑如何能在二维图像中得到体现?什么是摄影?

我想做实验。

实验的内容是什么?

在开始的时候,我是相当谨慎的。我布置不同的 "场景",拍摄即时的宝丽来照片,然后把所有东西放回原处。不知怎的,我想有人会回来看它的样子,来检查我在做什么。但一段时间后,我在这所住宅里很有家的感觉,变得更放松了。我甚至开始在那里做饭,使用马特松的餐具。

多年来,我多次重新布置这个空间,以发掘其隐藏的潜力。解构并超越其明显的空间组织。我只是在测试。构思图像,拍照,打印。

这所住宅成了一个试验台。我甚至把天花板的一部分拆下来,以拓展新的空间可能性。在我的书《索德拉库尔客弗洛萨库尔》(Södrakull Frösakull)中,呈现了几个不同的房间。这些图像被融合成一个系列,给人的印象是这所住宅是一个比它大得多的空间。但看一下平面图,你会意识到这是一个小住宅——包含外部的露台,大约10 x 15米。

对我来说,这整段经历是一个完美的机会去质疑建筑图像是什么,或者它可以是什么。我在试验建筑和它的内部如何能帮助我创造吸引观众目光的图像。

你自己的作品在弗罗萨库尔的实验中是如何发展的?

在这个项目中,我探索了不同的表现方式,探索如何展示和表现空间。这就是为什么我现在可以轻松地在委托项目和我自己的艺术项目之间来回转换。这关乎于处理不同类型的表现和想法——现在我知道如何从与客户审美偏好相协调的表现模式切换到我个人参与的模式。

我自己的工作总是涉及到图像、历史和摄影。当我做委托时,我不是一个艺术家。但我用我的艺术知识,以图像的形式加强客户的工作。

一开始,我只是到房子里去拍照。但过了一段时间,我不得不重新启动我的思维,看看我到底看到了什么。我喜欢用4 x 5的模拟相机,用它你工作得非常慢。你的思维会变慢。你开始思考出现在镜头前的东西。你集中精力。所有这一切都导致了观察,并在你的脑海中停留多年。

洞察力的一个常见问题是,它很快变得无意识和肤浅。你需要约束自己,跳出框框看问题。"你不能只见树木不见森林"。你看到一棵树的次数太多,以至于你最终停止了对它的感知。我经常告诉自己要重新开始——让我的头脑感知面前的事物,就像它第一次出现在那里一样。

你的书《索德拉库尔-弗洛萨库尔》展示了两所不同的住宅和接近它们的不同方式。

是的,在索德拉库尔的另一所住宅,是马特松的全职住所。当我第一次访问它时,没有人住在那里。它年久失修,我没有办法进入。我走了一圈,拍了一些偷窥者的照片。

我猜每个人都知道发现一个废弃的住宅并对它的内部情况感兴趣的感觉。你走近,试图用你的眼睛穿透内部。我想把这个时刻转化为照片。这些照片成为这本书的开始——更抽象的图像。

你认为被遗弃的夏季别墅比被遗弃的住宅激起了更深的悲伤感吗?

事情正在发生变化。我对摄影的想法一点也不怀旧。即使马特松的住宅代表了某种怀旧,它也以一种极端和集中的方式代表了深深扎根于现代瑞典社会的想法。马特松是一位重要的设计师。他的想法和喜好在他的项目中得到了明确的表达。他对自然主义、健康、轻盈、空气和阳光非常感兴趣。

马特松去了美国。他遇到了埃德加-考夫曼,MoMA的一位策展人。他被介绍到美国的建筑界。他遇到了密斯-凡-德-罗的客户范斯沃斯夫人。她甚至买了马特森的家具,我们在范斯沃斯宅的原始照片中看到的就是他的家具。在查尔斯和雷-伊姆斯在洛杉矶建造住宅的过程中,他拜访了他们。

当用1950年的塑料元素建造时,住宅并不是要永远存在的。另一方面,石头房子则可以矗立几个世纪。纸房子的基因是脆弱的。它将会消失。接受暂时存在的条件是有趣的,我认为。这是很放松的。我想这就是我喜欢弗洛萨库尔的夏季别墅的原因。它迫使你质疑你对住宅的想法。在这样的结构中,你开始以一种不太传统的方式行事。你不做明显的事情,它未定义的开放特性邀请你去尝试,它创造了意想不到的东西。这就是它吸引我的地方。我发现它是健康的,对心灵有好处。

这所住宅没有一个中心。没有中央供暖;温暖的开始和停止的定义是分散的。这所住宅不知何故无处不在,也无处不有。它不是一个能用简单的联想和可预测性来取悦你的住宅。正是由于这些原因,我发现弗洛萨库尔宅比悲伤或怀旧更有趣和普遍。

我也几乎参观了马特松的所有其他住宅。我去看他们,因为我相信他们会帮助我更好地理解他的作品和想法(我还拍了一部关于他在瑞典科斯塔镇的排屋的电影)。有时我遇到业主吹嘘他们原始的椅子,穿着50年代的夹克。有些人喜欢被过去控制,被对美好时代的回忆或任意的情绪控制。这让我感到惊讶。

我试图在我的作品中排除所有的感伤。即使主题是多愁善感的,我也不想把它作为一个信息来预示。我认为这很危险。

而现在,住宅的出售切断了去那里的所有可能性吗?

是的,这是件好事。如果我还有钥匙,我会去那里,拍更多照片。在某些时候,我想停下来。有一次,业主甚至问我是否想买下这所住宅!

我拒绝了,因为如果我买了它,我就会成为它的俘虏。我对它是如此痴迷。

你迷恋的是什么?

如何制作有趣的图像。

你现在正在研究哪些想法?

对物体的感知和物体本身之间的区别。

在我的作品中,物体本身没有那么重要,而是它所允许的感知实验。然而,图像总是在某种程度上是一种描述。你无法摆脱这一点。使用模拟胶片,摄影是对你面前的世界的一种慰藉,但这是一种技术性的再现。相机不是一台机器。它是一种仪器。使用不同的镜头,我阐明了我对感知和代表的想法,不管对象是什么。

它不关乎于材料,它不关乎于对象,它不关乎于主题。它关乎于你如何接近它,你如何表达它。一旦你作为一个建筑师或艺术家理解了这一点,就会改变你看问题的方式。当你作为一个记录者工作时,它是关于那里的东西。但当你作为一个艺术家,或作为一个图像制作者工作时,它是事实和想象力的结合,正如作者彼得-纳达斯(Péter Nádas)在《奥夫》一书中所指出的,我为赫尔佐格和德梅隆和艾未未的蛇形画廊项目所做的书。可以这么说,我借用建筑来创造一个 "自主空间"。

我将进一步探索这些主题——感知、流离失所、边缘空间——在一个西格德-卢埃伦茨的项目中,我从2000年开始就在做这件事了。

2022年11月5日

ミカエル・オルソン:2000年頃のことです。フロサクルにある、ブルーノ・マットソンが1960年にデザインしたサマーハウスに行くことができました。到着して中に入ると、そこが何年も手つかずであったことに気づきました。オリジナルの家具やオブジェ、カトラリー、それにマットソンの私物がたくさん残っていました。家は劣化していました。壁にはカビが生えていましたし、繊維強化プラスチックの屋根は、黄味がかってきていました。ところが、家が自然へと還り始めてもなお、その優美で自然体な姿は、残されていました。

最初は、引力と反力の入り混じった感覚を感じました。この感覚は何なのか、居ても立っても居られなくなり、この家の鍵を借りて、撮影プロジェクトを始めても良いか、とオーナーに聞いてみることにしたのです。撮影を終えるには、ここにもっと長くいるべきだと感じたのです。この建物がどう変化するのか、それに何が私を惹きつけているのか知る必要があると思ったのです。

鍵を手に入れることができ、私は何年もの間、いつでもそこへ行くことができました。その間、この家を使う人は、本当に誰もいませんでした。私は、一人でいることはあっても、他に誰かを呼ぶことはありませんでした。それは、芸術的探求のための場所でした。夏の間は、長く滞在することができました。冬や春は、とても寒かったですね。外が寒い日は、中はもっと寒かったくらいです。私の写真のイメージからも、そのことがわかると思います。部屋の中のバケツの水が、固く凍っています。3月の始めのことですよ。

この家は、マットソンの住まいに対する考えが示された実寸大のテストなのです。動く壁や、タイヤのついたストーブ。本当に、中でも外でも料理ができますよ。それに、マットソンは、外で寝るときもありました。昼間は、家の中から外を観察すると、ガラスや波板プラスチックの壁越しに、自然が見えてきます。

自然は、物事の現象が投影された景色となっています。風が木々を揺らすのがわかるでしょう。夜間は、それとは逆のことが起きます。この家が、通り過ぎる人々にとっての景色となるのです。自然は、暗闇のなかへ消え、動くシルエットが現れてきます。シルエットは、リビングルームでは、くっきりと明瞭に。そして中庭では、ぼんやりと。中庭側のプラスチックパネルが、シルエットの形を歪め、輪郭を柔らかくしているのです。

私は、写真家、そしてアーティストとして、この家に関わってきました。画家が自分のスタジオに行くのと同じように。その内部へと飛び込み、イメージメイキングの奥深さや可能性を探っていきました。次のような問いが私を導いてくれました。

二次元のイメージの中に、建築はいかにして表現され得るのだろうか?写真とは何なのだろうか?

ただ、実験をしてみたかったのです。

実験とは、どういったものだったのでしょうか?

最初、私はかなり警戒していました。全てを元あった姿に戻す前に、さまざまな「セッティング」をして、サクッとポラロイドで撮影しました。どういうわけか、誰かがここへ戻ってきて、私がここで何をしていたのか、チェックするのではないかと思ってしまったのです。ですが、しばらくすると、家にいるようにくつろげるようになって、リラックスできるようになりました。料理もするほどに。マットソンのカトラリーでね。

何年にもわたって、この家に秘められたポテンシャルを明らかにしようと、繰り返し空間をアレンジし直しました。見かけ上の空間の構成を崩し、その先にあるものを見るために。ひたすらテストをしていました。イメージを組み立て、写真を撮り、印刷し、の繰り返しでした。

この家は、テストベッドになっていたのです。天井の一部をも取り払い、空間の新しい可能性を広げようとも試みました。私の作品集「Södrakull Frösakull」には、いくつかの異なる部屋が写されています。これらのイメージは、ひとつのシリーズになっていて、この家を、実際よりも大きな空間に感じさせています。平面図を見ると、小さい家だということがわかると思います。外部のパティオを含んでも、せいぜい10m×15mくらいのものです。

私にとっては、ここでの経験全てが、建築のイメージとは何なのか、何になり得るのか、といった問いを投げかける絶好の機会でした。見る人の視線をひきつけるイメージを作るには、建物やインテリアがどう役立つものなのか、が実験できたのです。

フロサクルで実験を行う中で、あなたの作品はどう進化したのでしょうか?

このプロジェクトの間、空間の見せ方や表象に対する、さまざまな表現方法を探求することができました。それで今では、コミッションワークと自分自身のアートワークとの間を、簡単に行き来できるようになったのです。さまざまな表現方法やアイデアをどう扱うか、ということです。つまり、クライアントの美的な好みと調和する表現のモードから、私の美的な好みを優先した個人的な取り組みのモードへと切り替える方法が、今ではわかるのです。

私の作品は、常にイメージを扱っています。それに歴史と写真。コミッションワークは、アーティストとしては行いません。ですが、アーティストとしての知識を活かしながら、イメージの形成という点においては、クライアントの作品を強化することできます。

当初は、あの家に行って写真を撮るだけでした。ところが、しばらくたって、私が本当に見たものは、何だったのか確かめるために、気持ちを入れ替える必要を感じました。4×5のアナログカメラを使うのが好きなのですが、そうすると作業が非常にゆっくりになるのです。すると、気持ちもゆったりとしてきます。カメラの前に、何が現れているのかを考え始めるようになり、集中できるのです。こういったことの全てが、何年も心に刻まれるような観測を導いてくれるのだと思います。

知覚における一般的な問題は、それがすぐに不注意で表面的なものになってしまうことです。枠の外側に目を向けるよう、自分を律する必要があるのです。「木を見ていては、森は見え」ません。幾度となく木を見ていると、遂には、認識すらしなくなるものです。私はよく自分自身に、再スタートするように言い聞かせています。目の前にあるものが、初めてそこにあるかのように知覚するためです。

あなたの作品集「Södrakull Frösakull」では、二つの家で二つの撮影方法が試みられていますね。

そうです。もう一つの家は、ソドラクルにあるマットソンの日常生活の家です。私が訪れたときには、誰も住んでいませんでした。荒廃していて中に入ることもできませんでした。それで私は周囲を歩いて、のぞき見るようにして撮影したのです。

廃屋を見つけると、中がどうなっているのか気になってしまう感覚は、誰しもが持つものだと思います。あなたは、家へと近づいていき、あなたの目が家の中へと浸透していく。この瞬間を写真で伝えたかったのです。これらの写真は、本の最初の方に載せています。抽象的なイメージとして。

見捨てられたサマーハウスからは、同じく見捨てられた彼の家よりも、さらに深い悲しみのようなものが喚起されたのでしょうか?

状況は、変化するものです。私の写真に対する考え方は、全くノスタルジックなものではありません。マットソンの家からは、ある種のノスタルジアが感じられるかもしれません。ですが、むしろそこには、現代のスウェーデン社会に深く根差した考えが、極度に集中した形で表れています。マットソンは影響力のあるデザイナーでした。彼のプロジェクトからは、彼の考えや好みが、はっきりとわかります。彼は、自然主義的で、健康や明るさ、それに空気や太陽といったものに、非常に強い興味をもっていました。

マットソンは、アメリカに行き、MoMAのキュレーターであるエドガー・カウフマンと会っています。彼は、アメリカ建築界で紹介され、ミース・ファンデル・ローエや彼のクライアントであったミセス・ファンズワースに会っています。彼女は、マットソンの家具を購入していましたし、ファンズワース邸のオリジナル写真に映っているのは、まさに彼の家具なのです。チャールズ&レイ・イームズには、ロサンゼルスの彼らの家が、建設中のときに会っています。

1950年代にプラスチックで家を建設するということは、家がずっとそこにあるわけでないことを意味しています。石の家であれば、何世紀にもわたって存在するでしょうけれども。ペーパーハウスはDNA的にも脆いものですし、消えてしまうものです。そういったものを、一時的な存在として受容することは、楽しいことなのだと思います。とても気楽なものですし。だから私は、フロサクルのサマーハウスが好きなんだと思います。家とは一体何なのか、といった問いを投げかけてくれるのです。そういった中では、慣習にとらわれずに行動するものです。決まり切ったことなど、やらなくなる。未定義でオープンな性質が、いろんな事をやってみようという気にさせてくれるのだと思います。予期せぬ創造が生まれ、それに魅了される。そういったことが、健康にも、心にとっても良いことだと気づきました。

サマーハウスには中心がありません。セントラルヒーティングもありません。つまりどこから暖かくなるのか、あるいはどこで終わるのかが曖昧です。この家は、どこにでもあるし、どこにもない、という感覚でしょうか。この家は、あなたに簡単についてきてくれるものでもないですし、理解しやすいものでもない。慰めてもくれない。こういった点で、フロサクルの家は、とても興味深く、普遍的なものだと思うのです。悲しみやノスタルジーといったものよりもね。

マットソンのデザインした他の家にも、ほとんど行きました。彼の作品や考えをより理解できるだろうと思ったからです。(スウェーデンの町コスタにある、彼のデザインした長屋の映像も撮りました。)オリジナルの椅子を自慢してくれるオーナーや、50年代のジャケットを来ているオーナーに会ったりもしました。過去や、良かった時代の記憶、それに恣意的な感情、といったものにコントロールされるのが好きな人もいるのですよね。驚きました。

私は、作品からあらゆるセンチメントを排除しようとしているのです。モチーフがセンチメンタルなものであっても、それをメッセージとして伝えるようなことはしたくない。とても危険だと思います。

家は、もう売却されてしまいましたし、そこにはもう行けないのですよね?

そうですね。良かったです。まだ鍵を持っていたら、またそこに行って、写真を撮ってしまう。いつかは辞めたかったのです。ある時、オーナーが私に、その家を買わないかとさえ言ってきました!

断りましたよ。購入していたら、私はその家の囚人となっていたでしょう。本当にとりつかれていましたから。

何にとりつかれていたのですか?

面白いイメージを作ることに、です。

今は、どういった考えで作品を作っているのでしょうか?

対象への知覚と、対象そのものの違いについて、です。

私の作品では、対象それ自体が重要なわけではなく、その対象が生み出す知覚的実験の方が重要です。ところが、イメージは常に何らかの描写であって、そこから逃れることはできません。アナログフィルムで撮った写真は、あなたの目の前に映る世界のレリーフです。技術的な複製ではありますが。それでも、カメラはマシーンではないのです。 装置なのです。私は、様々なレンズを用いながら、私の知覚と表現に対する考えを明瞭にしていくのです。撮る対象がなんであれ関係ありません。

素材や、対象や、モチーフ。そういった対象が問題なのではなく、どのようなアプローチでそれを明瞭にしていくか、なのです。建築家、あるいはアーティストとして、このことを理解できるようになると、物事の見方も変わると思います。ドキュメンタリー作家であれば、そこにあるものが重要です。ただ、あなたがアーティストや、イメージメーカーなのであれば、事実とイマジネーションとを組み合わせる事が重要です。ヘルツォーク&ド・ムーロンとアイ・ウェイウェイのサーペンタイン・ギャラリーを撮影した本「on | auf」でピーター・ナダスが、そのことを指摘してくれました。私の仕事はいわば、建物を借りた「自律的空間」の創造なのだと。

知覚、転置、境界の空間。こういったテーマをもっと探求していきたいですね。とりわけ、シーグルド・レヴェレンツのプロジェクトにおいては。かれこれ、2000年から取り組んできているプロジェクトですから。

2022年11月5日

Mikael Olsson: Around 2000, I got access to Bruno Mathsson’s summer house in Frösakull, which he designed in 1960. I arrived, entered and realised that it had been untouched for years. It was full of original furniture and objects, including cutlery and Mathsson’s personal belongings. Parts of the house were degraded; fungus grew on walls, the fibre reinforced plastic roof had become yellowish. Despite nature starting to reclaim the house, its elegance and naturalness remained.

Initially, I felt a mix of attraction and repulsion. I couldn’t stop thinking about what this feeling meant. I decided to ask the owners if I could have the keys to the house and initiate a photographic project about it. To finish the work, I felt that I needed to stay there longer, I needed to explore how the building was changing and what effect it was having on me.

I got the keys, and for many years, I went there whenever I wanted. Nobody was really using the house during this time. I was there by myself and did not invite other people. It was a place of artistic exploration. During the summer I went there for longer periods. In the winter or spring, it got very cold; when it was cold outside, it was even colder inside. You can sense this in some of my images. Inside, there were buckets of water, frozen solid, even in the beginning of May.

The house is a full-scale test of Mathsson’s ideas on how to dwell. Movable walls, a stove on wheels. You could actually cook both inside and outside. And Mathsson himself sometimes even slept outside. When looking out from the house during the daytime, you see nature either through glass or corrugated plastic walls.

Nature becomes a scene where things happen. You observe it and can see how the wind moves the trees. In the evening, the opposite is true. The house is a scene to the people passing by. Nature disappears into darkness and moving silhouettes emerge. They are sharp and explicit in the living room and blurred in the courtyard, because of how the plastic panels distort the shapes and soften the contours.

As a photographer, an artist, I treated the house as a painter going to his studio. I went there to dive in and explore the depths and possibilities of image making. The questions that guided me were:

How can architecture be represented in a two-dimensional image? What is photography? I wanted to experiment.

WHAT WERE THE EXPERIMENTS ABOUT?

In the beginning, I was quite cautious. I arranged different ‘settings’ and took fast Polaroid’s, before putting everything back how it had been. Somehow, I thought that somebody would come back to see how it looked, to check what I was up to. But after a while I felt quite at home in the house and became more relaxed. I even started cooking there, using Mathsson’s cutlery.

Over the years, I rearranged the space many times to uncover its hidden potential; to deconstruct and see beyond its obvious spatial organisation. I was just testing. Composing images, taking photographs, printing.

The house became a testbed. I even took parts of the ceiling down to unfold new spatial possibilities. In my book Södrakull Frösakull several different rooms are present. These images are fused into a series which gives the impression of the house as a much larger space than it is. Looking at the floor plan, you realise that it’s a small house – around 10 x 15 meters, including the external patio.

For me the whole experience was a perfect opportunity to question the idea of what an image of architecture was, or what it could be. I was experimenting with how the building and its interior could help me create images that would attract the gaze of a viewer.

HOW DID YOUR OWN WORK EVOLVE DURING THE EXPERIMENTS AT FRÖSAKULL?

During the project I explored different ways of representation, of how to show and represent space. That’s why I can now easily shift back and forth between commissions and my own artistic projects. It’s about handling different kinds of representations and ideas – and now I know how to switch from a representation mode which harmonises with my client’s, aesthetics preferences to the one that engages me personally.

My own work always deals with image, history and photography. When I do commissions, I am not an artist. But I use my artistic knowledge to strengthen the work of the client in the form of an image.

At the start, I just went to the house and photographed. But after a while, I had to restart my mind to see what I actually saw. I like to use a 4 x 5 analogue camera and with this you work really slowly. Your mind slows down. You start thinking about what appears in front of the camera. You are concentrated. All this leads to observations that remain in your mind for years.

A common problem of perception is that it quickly becomes mindless and superficial. You need to discipline yourself to look outside the box. „You can’t see the forest for the trees”. You’ve seen a tree so many times, that you eventually stop perceiving it. I often tell myself to restart – to allow my mind to perceive what is in front of it, as if it were there for the first time.

YOUR BOOK SÖDRAKULL FRÖSAKULL SHOWS TWO DIFFERENT HOUSES AND DIFFERENT WAYS OF APPROACHING THEM.

Yes, the other house, in Södrakull, was Mathsson’s full time residence. When I first visited it, nobody lived there. It was in disrepair, and I didn’t have access. I walked around and took Peeping Tom images.

I guess everybody recognises the feeling of finding an abandoned house and being interested in how it looks inside. You go close, and with your eyes you try to penetrate the interior. I wanted to translate this moment into photographs. Those pictures became the beginning of the book – the more abstract images.

DO YOU THINK THE ABANDONED SUMMER HOUSE PROVOKES A DEEPER FEELING OF SADNESS THAN THE ABANDONED RESIDENCE?

Things are changing. My idea of photography is not at all nostalgic. Even if Mathsson’s house represents some kind of nostalgia, it also represents, in an extreme and concentrated way, ideas that are deeply rooted in the modern Swedish society. Mathsson was an important designer. He had ideas and preferences that clearly found expression in his projects. He was very interested in naturism, fitness, lightness, air, sun.

Mathsson went to the USA. He met Edgar Kaufmann, a curator at MoMA. He was introduced to the American architectural scene. He met Mies van der Rohe’s client Mrs. Farnsworth. She even bought Mathsson’s furniture, and it is his furniture that we see in the original photographs of the Farnsworth House. He visited Charles and Ray Eames during the construction of their house in Los Angeles.

When building with 1950’s plastic elements, the house is not meant to be there forever. A stone house, on the other hand, can stand for centuries. A paper house has fragility in its DNA. It will disappear. To accept the condition of temporary existence is interesting, I think. It’s very relaxing. I guess that it is what I like about the summer house in Frösakull. It forces you to question your idea of what a house is. In such a structure you start to act in a less conventional way. You don’t do the obvious. Its undefined open character invites you to try things out. It creates the unexpected. That’s what attracts me to it. I find it healthy and good for the mind.

The house doesn’t have a center. There is no central heating; the definition of where the warmth begins and where it stops is diffuse. The house is somehow everywhere and nowhere. It’s not a house that comforts you with easy associations and predictability. It is for these reasons, that I find the Frösakull house much more interesting and universal than sad or nostalgic.

I have visited nearly all of Mathsson’s other houses, too. I went to see them because I believed that they would help me to understand his work and ideas better (and I also made a film on his row houses in the Swedish town of Kosta). Sometimes I met owners boasting about original chairs and wearing jackets from the fifties. Some people like being controlled by the past, by memories of better times or arbitrary sentiments. This surprises me.

I try to exclude all sentimentality from my work. Even if the motif is sentimental, I don’t want to herald this as a message. I think it’s dangerous.

AND NOW, DID THE SALE OF THE HOUSE CUT ALL POSSIBILITIES OF GOING THERE?

Yes, and it’s a good thing. If I still had the keys, I would go there and take more pictures. At some point, I wanted to stop. At one point the owners even asked if I wanted to buy the house!

I declined, because if I had bought it, I would have become its prisoner. I was so obsessed by it.

WHAT WERE YOU OBSESSED ABOUT?

How to make interesting images.

WHICH IDEAS ARE YOU WORKING WITH RIGHT NOW?

The difference between the perception of the object and the object itself.

In my work, the object itself is less important than the perceptive experiments it allows. However, an image is always a description in some way. You can’t get away from that. Using analogue film, photography is a relief of the world in front of you. But it’s a technical reproduction. A camera is not a machine. It’s an apparatus. Using different lenses, I articulate my ideas on perception and representation, regardless of the object.

It’s not about the material, it’s not about the object, it’s not about the motif. It’s about how you approach it, how you articulate it. Once you understand this as an architect or an artist it changes the way you look at things. When you work as a documentarist, it’s about what’s there. But when you work as an artist, or as an image maker, it’s a combination of facts and imagination, as the author Péter Nádas notes in on | auf, the book I did on the Serpentine Gallery project by Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei. I, so to speak, borrow the buildings to create an “autonomous space”.

I will explore these themes – perception, displacement, liminal spaces – further in a project on Sigurd Lewerentz, which I have been working on since 2000.

05.11.2022

米卡尔-奥尔森: 2000年左右,我进入了布鲁诺-马特松在弗洛萨库尔的夏季别墅,这是他在1960年设计的。我来到这里,进入后才发现,它已经多年没有被人动过了。那里充满了当初的的家具和物品,包括餐具和马特松的私人物件。住宅的某些部分已经退化了;墙壁上长出了真菌,纤维增强复合材料(FRP)的屋顶已经变黄了。尽管大自然开始回收这所住宅,但它的优雅和自然性仍然存在。

起初,我感觉到一种吸引力和排斥力的混合。我无法停止思考这种感觉意味着什么。我决定问问业主,我是否可以拥有这所住宅的钥匙,并启动一个关于它的摄影项目。为了完成这项工作,我觉得我需要在那里待更长的时间,我需要探索这个建筑是如何变化的,它对我有什么影响。

我拿到了钥匙,许多年来,只要我想,我就会去那里。在这段时间里,没有人真正使用这所住宅。我独自在那儿,没有邀请其他人。那是一个探索艺术的地方。在夏天,我去那里的时间更长。在冬天或春天,它变得非常冷;当外面寒冷,里面更冷。你可以从我的一些图片中感受到这一点。里面有一桶桶的水,冻得很结实,甚至在五月初的时候。

这所住宅是对马特松对居住方式的想法的一次全面测试。可移动的墙壁,带轮子的火炉。你实际上在室内和室外都可以做饭。马特松本人有时甚至睡在外面。白天从住宅里向外看时,你可以通过玻璃或波纹板墙看到大自然。

大自然成为一个事情发生的场景。你观察它,可以看到风如何移动树木。到了晚上,情况就相反了。对路过的人来说,房子是一个场景。大自然消失在黑暗中,移动的剪影出现了。它们在客厅里是清晰的,在院子里是模糊的,因为塑料板扭曲了形状,软化了轮廓。

作为一个摄影师,一个艺术家,我对待这所住宅就像一个画家去他的工作室。我去那里是为了潜入并探索图像制作的深度和可能性。引导我的问题是: 建筑如何能在二维图像中得到体现?什么是摄影?

我想做实验。

实验的内容是什么?

在开始的时候,我是相当谨慎的。我布置不同的 "场景",拍摄即时的宝丽来照片,然后把所有东西放回原处。不知怎的,我想有人会回来看它的样子,来检查我在做什么。但一段时间后,我在这所住宅里很有家的感觉,变得更放松了。我甚至开始在那里做饭,使用马特松的餐具。

多年来,我多次重新布置这个空间,以发掘其隐藏的潜力。解构并超越其明显的空间组织。我只是在测试。构思图像,拍照,打印。

这所住宅成了一个试验台。我甚至把天花板的一部分拆下来,以拓展新的空间可能性。在我的书《索德拉库尔客弗洛萨库尔》(Södrakull Frösakull)中,呈现了几个不同的房间。这些图像被融合成一个系列,给人的印象是这所住宅是一个比它大得多的空间。但看一下平面图,你会意识到这是一个小住宅——包含外部的露台,大约10 x 15米。

对我来说,这整段经历是一个完美的机会去质疑建筑图像是什么,或者它可以是什么。我在试验建筑和它的内部如何能帮助我创造吸引观众目光的图像。

你自己的作品在弗罗萨库尔的实验中是如何发展的?

在这个项目中,我探索了不同的表现方式,探索如何展示和表现空间。这就是为什么我现在可以轻松地在委托项目和我自己的艺术项目之间来回转换。这关乎于处理不同类型的表现和想法——现在我知道如何从与客户审美偏好相协调的表现模式切换到我个人参与的模式。

我自己的工作总是涉及到图像、历史和摄影。当我做委托时,我不是一个艺术家。但我用我的艺术知识,以图像的形式加强客户的工作。

一开始,我只是到房子里去拍照。但过了一段时间,我不得不重新启动我的思维,看看我到底看到了什么。我喜欢用4 x 5的模拟相机,用它你工作得非常慢。你的思维会变慢。你开始思考出现在镜头前的东西。你集中精力。所有这一切都导致了观察,并在你的脑海中停留多年。

洞察力的一个常见问题是,它很快变得无意识和肤浅。你需要约束自己,跳出框框看问题。"你不能只见树木不见森林"。你看到一棵树的次数太多,以至于你最终停止了对它的感知。我经常告诉自己要重新开始——让我的头脑感知面前的事物,就像它第一次出现在那里一样。

你的书《索德拉库尔-弗洛萨库尔》展示了两所不同的住宅和接近它们的不同方式。

是的,在索德拉库尔的另一所住宅,是马特松的全职住所。当我第一次访问它时,没有人住在那里。它年久失修,我没有办法进入。我走了一圈,拍了一些偷窥者的照片。

我猜每个人都知道发现一个废弃的住宅并对它的内部情况感兴趣的感觉。你走近,试图用你的眼睛穿透内部。我想把这个时刻转化为照片。这些照片成为这本书的开始——更抽象的图像。

你认为被遗弃的夏季别墅比被遗弃的住宅激起了更深的悲伤感吗?

事情正在发生变化。我对摄影的想法一点也不怀旧。即使马特松的住宅代表了某种怀旧,它也以一种极端和集中的方式代表了深深扎根于现代瑞典社会的想法。马特松是一位重要的设计师。他的想法和喜好在他的项目中得到了明确的表达。他对自然主义、健康、轻盈、空气和阳光非常感兴趣。

马特松去了美国。他遇到了埃德加-考夫曼,MoMA的一位策展人。他被介绍到美国的建筑界。他遇到了密斯-凡-德-罗的客户范斯沃斯夫人。她甚至买了马特森的家具,我们在范斯沃斯宅的原始照片中看到的就是他的家具。在查尔斯和雷-伊姆斯在洛杉矶建造住宅的过程中,他拜访了他们。

当用1950年的塑料元素建造时,住宅并不是要永远存在的。另一方面,石头房子则可以矗立几个世纪。纸房子的基因是脆弱的。它将会消失。接受暂时存在的条件是有趣的,我认为。这是很放松的。我想这就是我喜欢弗洛萨库尔的夏季别墅的原因。它迫使你质疑你对住宅的想法。在这样的结构中,你开始以一种不太传统的方式行事。你不做明显的事情,它未定义的开放特性邀请你去尝试,它创造了意想不到的东西。这就是它吸引我的地方。我发现它是健康的,对心灵有好处。

这所住宅没有一个中心。没有中央供暖;温暖的开始和停止的定义是分散的。这所住宅不知何故无处不在,也无处不有。它不是一个能用简单的联想和可预测性来取悦你的住宅。正是由于这些原因,我发现弗洛萨库尔宅比悲伤或怀旧更有趣和普遍。

我也几乎参观了马特松的所有其他住宅。我去看他们,因为我相信他们会帮助我更好地理解他的作品和想法(我还拍了一部关于他在瑞典科斯塔镇的排屋的电影)。有时我遇到业主吹嘘他们原始的椅子,穿着50年代的夹克。有些人喜欢被过去控制,被对美好时代的回忆或任意的情绪控制。这让我感到惊讶。

我试图在我的作品中排除所有的感伤。即使主题是多愁善感的,我也不想把它作为一个信息来预示。我认为这很危险。

而现在,住宅的出售切断了去那里的所有可能性吗?

是的,这是件好事。如果我还有钥匙,我会去那里,拍更多照片。在某些时候,我想停下来。有一次,业主甚至问我是否想买下这所住宅!

我拒绝了,因为如果我买了它,我就会成为它的俘虏。我对它是如此痴迷。

你迷恋的是什么?

如何制作有趣的图像。

你现在正在研究哪些想法?

对物体的感知和物体本身之间的区别。

在我的作品中,物体本身没有那么重要,而是它所允许的感知实验。然而,图像总是在某种程度上是一种描述。你无法摆脱这一点。使用模拟胶片,摄影是对你面前的世界的一种慰藉,但这是一种技术性的再现。相机不是一台机器。它是一种仪器。使用不同的镜头,我阐明了我对感知和代表的想法,不管对象是什么。

它不关乎于材料,它不关乎于对象,它不关乎于主题。它关乎于你如何接近它,你如何表达它。一旦你作为一个建筑师或艺术家理解了这一点,就会改变你看问题的方式。当你作为一个记录者工作时,它是关于那里的东西。但当你作为一个艺术家,或作为一个图像制作者工作时,它是事实和想象力的结合,正如作者彼得-纳达斯(Péter Nádas)在《奥夫》一书中所指出的,我为赫尔佐格和德梅隆和艾未未的蛇形画廊项目所做的书。可以这么说,我借用建筑来创造一个 "自主空间"。

我将进一步探索这些主题——感知、流离失所、边缘空间——在一个西格德-卢埃伦茨的项目中,我从2000年开始就在做这件事了。

2022年11月5日

ミカエル・オルソン:2000年頃のことです。フロサクルにある、ブルーノ・マットソンが1960年にデザインしたサマーハウスに行くことができました。到着して中に入ると、そこが何年も手つかずであったことに気づきました。オリジナルの家具やオブジェ、カトラリー、それにマットソンの私物がたくさん残っていました。家は劣化していました。壁にはカビが生えていましたし、繊維強化プラスチックの屋根は、黄味がかってきていました。ところが、家が自然へと還り始めてもなお、その優美で自然体な姿は、残されていました。

最初は、引力と反力の入り混じった感覚を感じました。この感覚は何なのか、居ても立っても居られなくなり、この家の鍵を借りて、撮影プロジェクトを始めても良いか、とオーナーに聞いてみることにしたのです。撮影を終えるには、ここにもっと長くいるべきだと感じたのです。この建物がどう変化するのか、それに何が私を惹きつけているのか知る必要があると思ったのです。

鍵を手に入れることができ、私は何年もの間、いつでもそこへ行くことができました。その間、この家を使う人は、本当に誰もいませんでした。私は、一人でいることはあっても、他に誰かを呼ぶことはありませんでした。それは、芸術的探求のための場所でした。夏の間は、長く滞在することができました。冬や春は、とても寒かったですね。外が寒い日は、中はもっと寒かったくらいです。私の写真のイメージからも、そのことがわかると思います。部屋の中のバケツの水が、固く凍っています。3月の始めのことですよ。

この家は、マットソンの住まいに対する考えが示された実寸大のテストなのです。動く壁や、タイヤのついたストーブ。本当に、中でも外でも料理ができますよ。それに、マットソンは、外で寝るときもありました。昼間は、家の中から外を観察すると、ガラスや波板プラスチックの壁越しに、自然が見えてきます。

自然は、物事の現象が投影された景色となっています。風が木々を揺らすのがわかるでしょう。夜間は、それとは逆のことが起きます。この家が、通り過ぎる人々にとっての景色となるのです。自然は、暗闇のなかへ消え、動くシルエットが現れてきます。シルエットは、リビングルームでは、くっきりと明瞭に。そして中庭では、ぼんやりと。中庭側のプラスチックパネルが、シルエットの形を歪め、輪郭を柔らかくしているのです。

私は、写真家、そしてアーティストとして、この家に関わってきました。画家が自分のスタジオに行くのと同じように。その内部へと飛び込み、イメージメイキングの奥深さや可能性を探っていきました。次のような問いが私を導いてくれました。

二次元のイメージの中に、建築はいかにして表現され得るのだろうか?写真とは何なのだろうか?

ただ、実験をしてみたかったのです。

実験とは、どういったものだったのでしょうか?

最初、私はかなり警戒していました。全てを元あった姿に戻す前に、さまざまな「セッティング」をして、サクッとポラロイドで撮影しました。どういうわけか、誰かがここへ戻ってきて、私がここで何をしていたのか、チェックするのではないかと思ってしまったのです。ですが、しばらくすると、家にいるようにくつろげるようになって、リラックスできるようになりました。料理もするほどに。マットソンのカトラリーでね。

何年にもわたって、この家に秘められたポテンシャルを明らかにしようと、繰り返し空間をアレンジし直しました。見かけ上の空間の構成を崩し、その先にあるものを見るために。ひたすらテストをしていました。イメージを組み立て、写真を撮り、印刷し、の繰り返しでした。

この家は、テストベッドになっていたのです。天井の一部をも取り払い、空間の新しい可能性を広げようとも試みました。私の作品集「Södrakull Frösakull」には、いくつかの異なる部屋が写されています。これらのイメージは、ひとつのシリーズになっていて、この家を、実際よりも大きな空間に感じさせています。平面図を見ると、小さい家だということがわかると思います。外部のパティオを含んでも、せいぜい10m×15mくらいのものです。

私にとっては、ここでの経験全てが、建築のイメージとは何なのか、何になり得るのか、といった問いを投げかける絶好の機会でした。見る人の視線をひきつけるイメージを作るには、建物やインテリアがどう役立つものなのか、が実験できたのです。

フロサクルで実験を行う中で、あなたの作品はどう進化したのでしょうか?

このプロジェクトの間、空間の見せ方や表象に対する、さまざまな表現方法を探求することができました。それで今では、コミッションワークと自分自身のアートワークとの間を、簡単に行き来できるようになったのです。さまざまな表現方法やアイデアをどう扱うか、ということです。つまり、クライアントの美的な好みと調和する表現のモードから、私の美的な好みを優先した個人的な取り組みのモードへと切り替える方法が、今ではわかるのです。

私の作品は、常にイメージを扱っています。それに歴史と写真。コミッションワークは、アーティストとしては行いません。ですが、アーティストとしての知識を活かしながら、イメージの形成という点においては、クライアントの作品を強化することできます。

当初は、あの家に行って写真を撮るだけでした。ところが、しばらくたって、私が本当に見たものは、何だったのか確かめるために、気持ちを入れ替える必要を感じました。4×5のアナログカメラを使うのが好きなのですが、そうすると作業が非常にゆっくりになるのです。すると、気持ちもゆったりとしてきます。カメラの前に、何が現れているのかを考え始めるようになり、集中できるのです。こういったことの全てが、何年も心に刻まれるような観測を導いてくれるのだと思います。

知覚における一般的な問題は、それがすぐに不注意で表面的なものになってしまうことです。枠の外側に目を向けるよう、自分を律する必要があるのです。「木を見ていては、森は見え」ません。幾度となく木を見ていると、遂には、認識すらしなくなるものです。私はよく自分自身に、再スタートするように言い聞かせています。目の前にあるものが、初めてそこにあるかのように知覚するためです。

あなたの作品集「Södrakull Frösakull」では、二つの家で二つの撮影方法が試みられていますね。

そうです。もう一つの家は、ソドラクルにあるマットソンの日常生活の家です。私が訪れたときには、誰も住んでいませんでした。荒廃していて中に入ることもできませんでした。それで私は周囲を歩いて、のぞき見るようにして撮影したのです。

廃屋を見つけると、中がどうなっているのか気になってしまう感覚は、誰しもが持つものだと思います。あなたは、家へと近づいていき、あなたの目が家の中へと浸透していく。この瞬間を写真で伝えたかったのです。これらの写真は、本の最初の方に載せています。抽象的なイメージとして。

見捨てられたサマーハウスからは、同じく見捨てられた彼の家よりも、さらに深い悲しみのようなものが喚起されたのでしょうか?

状況は、変化するものです。私の写真に対する考え方は、全くノスタルジックなものではありません。マットソンの家からは、ある種のノスタルジアが感じられるかもしれません。ですが、むしろそこには、現代のスウェーデン社会に深く根差した考えが、極度に集中した形で表れています。マットソンは影響力のあるデザイナーでした。彼のプロジェクトからは、彼の考えや好みが、はっきりとわかります。彼は、自然主義的で、健康や明るさ、それに空気や太陽といったものに、非常に強い興味をもっていました。

マットソンは、アメリカに行き、MoMAのキュレーターであるエドガー・カウフマンと会っています。彼は、アメリカ建築界で紹介され、ミース・ファンデル・ローエや彼のクライアントであったミセス・ファンズワースに会っています。彼女は、マットソンの家具を購入していましたし、ファンズワース邸のオリジナル写真に映っているのは、まさに彼の家具なのです。チャールズ&レイ・イームズには、ロサンゼルスの彼らの家が、建設中のときに会っています。

1950年代にプラスチックで家を建設するということは、家がずっとそこにあるわけでないことを意味しています。石の家であれば、何世紀にもわたって存在するでしょうけれども。ペーパーハウスはDNA的にも脆いものですし、消えてしまうものです。そういったものを、一時的な存在として受容することは、楽しいことなのだと思います。とても気楽なものですし。だから私は、フロサクルのサマーハウスが好きなんだと思います。家とは一体何なのか、といった問いを投げかけてくれるのです。そういった中では、慣習にとらわれずに行動するものです。決まり切ったことなど、やらなくなる。未定義でオープンな性質が、いろんな事をやってみようという気にさせてくれるのだと思います。予期せぬ創造が生まれ、それに魅了される。そういったことが、健康にも、心にとっても良いことだと気づきました。

サマーハウスには中心がありません。セントラルヒーティングもありません。つまりどこから暖かくなるのか、あるいはどこで終わるのかが曖昧です。この家は、どこにでもあるし、どこにもない、という感覚でしょうか。この家は、あなたに簡単についてきてくれるものでもないですし、理解しやすいものでもない。慰めてもくれない。こういった点で、フロサクルの家は、とても興味深く、普遍的なものだと思うのです。悲しみやノスタルジーといったものよりもね。

マットソンのデザインした他の家にも、ほとんど行きました。彼の作品や考えをより理解できるだろうと思ったからです。(スウェーデンの町コスタにある、彼のデザインした長屋の映像も撮りました。)オリジナルの椅子を自慢してくれるオーナーや、50年代のジャケットを来ているオーナーに会ったりもしました。過去や、良かった時代の記憶、それに恣意的な感情、といったものにコントロールされるのが好きな人もいるのですよね。驚きました。

私は、作品からあらゆるセンチメントを排除しようとしているのです。モチーフがセンチメンタルなものであっても、それをメッセージとして伝えるようなことはしたくない。とても危険だと思います。

家は、もう売却されてしまいましたし、そこにはもう行けないのですよね?

そうですね。良かったです。まだ鍵を持っていたら、またそこに行って、写真を撮ってしまう。いつかは辞めたかったのです。ある時、オーナーが私に、その家を買わないかとさえ言ってきました!

断りましたよ。購入していたら、私はその家の囚人となっていたでしょう。本当にとりつかれていましたから。

何にとりつかれていたのですか?

面白いイメージを作ることに、です。

今は、どういった考えで作品を作っているのでしょうか?

対象への知覚と、対象そのものの違いについて、です。

私の作品では、対象それ自体が重要なわけではなく、その対象が生み出す知覚的実験の方が重要です。ところが、イメージは常に何らかの描写であって、そこから逃れることはできません。アナログフィルムで撮った写真は、あなたの目の前に映る世界のレリーフです。技術的な複製ではありますが。それでも、カメラはマシーンではないのです。 装置なのです。私は、様々なレンズを用いながら、私の知覚と表現に対する考えを明瞭にしていくのです。撮る対象がなんであれ関係ありません。

素材や、対象や、モチーフ。そういった対象が問題なのではなく、どのようなアプローチでそれを明瞭にしていくか、なのです。建築家、あるいはアーティストとして、このことを理解できるようになると、物事の見方も変わると思います。ドキュメンタリー作家であれば、そこにあるものが重要です。ただ、あなたがアーティストや、イメージメーカーなのであれば、事実とイマジネーションとを組み合わせる事が重要です。ヘルツォーク&ド・ムーロンとアイ・ウェイウェイのサーペンタイン・ギャラリーを撮影した本「on | auf」でピーター・ナダスが、そのことを指摘してくれました。私の仕事はいわば、建物を借りた「自律的空間」の創造なのだと。

知覚、転置、境界の空間。こういったテーマをもっと探求していきたいですね。とりわけ、シーグルド・レヴェレンツのプロジェクトにおいては。かれこれ、2000年から取り組んできているプロジェクトですから。

2022年11月5日

Mikael Olsson: Around 2000, I got access to Bruno Mathsson’s summer house in Frösakull, which he designed in 1960. I arrived, entered and realised that it had been untouched for years. It was full of original furniture and objects, including cutlery and Mathsson’s personal belongings. Parts of the house were degraded; fungus grew on walls, the fibre reinforced plastic roof had become yellowish. Despite nature starting to reclaim the house, its elegance and naturalness remained.

Initially, I felt a mix of attraction and repulsion. I couldn’t stop thinking about what this feeling meant. I decided to ask the owners if I could have the keys to the house and initiate a photographic project about it. To finish the work, I felt that I needed to stay there longer, I needed to explore how the building was changing and what effect it was having on me.

I got the keys, and for many years, I went there whenever I wanted. Nobody was really using the house during this time. I was there by myself and did not invite other people. It was a place of artistic exploration. During the summer I went there for longer periods. In the winter or spring, it got very cold; when it was cold outside, it was even colder inside. You can sense this in some of my images. Inside, there were buckets of water, frozen solid, even in the beginning of May.

The house is a full-scale test of Mathsson’s ideas on how to dwell. Movable walls, a stove on wheels. You could actually cook both inside and outside. And Mathsson himself sometimes even slept outside. When looking out from the house during the daytime, you see nature either through glass or corrugated plastic walls.

Nature becomes a scene where things happen. You observe it and can see how the wind moves the trees. In the evening, the opposite is true. The house is a scene to the people passing by. Nature disappears into darkness and moving silhouettes emerge. They are sharp and explicit in the living room and blurred in the courtyard, because of how the plastic panels distort the shapes and soften the contours.

As a photographer, an artist, I treated the house as a painter going to his studio. I went there to dive in and explore the depths and possibilities of image making. The questions that guided me were:

How can architecture be represented in a two-dimensional image? What is photography? I wanted to experiment.

WHAT WERE THE EXPERIMENTS ABOUT?

In the beginning, I was quite cautious. I arranged different ‘settings’ and took fast Polaroid’s, before putting everything back how it had been. Somehow, I thought that somebody would come back to see how it looked, to check what I was up to. But after a while I felt quite at home in the house and became more relaxed. I even started cooking there, using Mathsson’s cutlery.

Over the years, I rearranged the space many times to uncover its hidden potential; to deconstruct and see beyond its obvious spatial organisation. I was just testing. Composing images, taking photographs, printing.

The house became a testbed. I even took parts of the ceiling down to unfold new spatial possibilities. In my book Södrakull Frösakull several different rooms are present. These images are fused into a series which gives the impression of the house as a much larger space than it is. Looking at the floor plan, you realise that it’s a small house – around 10 x 15 meters, including the external patio.

For me the whole experience was a perfect opportunity to question the idea of what an image of architecture was, or what it could be. I was experimenting with how the building and its interior could help me create images that would attract the gaze of a viewer.

HOW DID YOUR OWN WORK EVOLVE DURING THE EXPERIMENTS AT FRÖSAKULL?

During the project I explored different ways of representation, of how to show and represent space. That’s why I can now easily shift back and forth between commissions and my own artistic projects. It’s about handling different kinds of representations and ideas – and now I know how to switch from a representation mode which harmonises with my client’s, aesthetics preferences to the one that engages me personally.

My own work always deals with image, history and photography. When I do commissions, I am not an artist. But I use my artistic knowledge to strengthen the work of the client in the form of an image.

At the start, I just went to the house and photographed. But after a while, I had to restart my mind to see what I actually saw. I like to use a 4 x 5 analogue camera and with this you work really slowly. Your mind slows down. You start thinking about what appears in front of the camera. You are concentrated. All this leads to observations that remain in your mind for years.

A common problem of perception is that it quickly becomes mindless and superficial. You need to discipline yourself to look outside the box. „You can’t see the forest for the trees”. You’ve seen a tree so many times, that you eventually stop perceiving it. I often tell myself to restart – to allow my mind to perceive what is in front of it, as if it were there for the first time.

YOUR BOOK SÖDRAKULL FRÖSAKULL SHOWS TWO DIFFERENT HOUSES AND DIFFERENT WAYS OF APPROACHING THEM.

Yes, the other house, in Södrakull, was Mathsson’s full time residence. When I first visited it, nobody lived there. It was in disrepair, and I didn’t have access. I walked around and took Peeping Tom images.

I guess everybody recognises the feeling of finding an abandoned house and being interested in how it looks inside. You go close, and with your eyes you try to penetrate the interior. I wanted to translate this moment into photographs. Those pictures became the beginning of the book – the more abstract images.

DO YOU THINK THE ABANDONED SUMMER HOUSE PROVOKES A DEEPER FEELING OF SADNESS THAN THE ABANDONED RESIDENCE?

Things are changing. My idea of photography is not at all nostalgic. Even if Mathsson’s house represents some kind of nostalgia, it also represents, in an extreme and concentrated way, ideas that are deeply rooted in the modern Swedish society. Mathsson was an important designer. He had ideas and preferences that clearly found expression in his projects. He was very interested in naturism, fitness, lightness, air, sun.

Mathsson went to the USA. He met Edgar Kaufmann, a curator at MoMA. He was introduced to the American architectural scene. He met Mies van der Rohe’s client Mrs. Farnsworth. She even bought Mathsson’s furniture, and it is his furniture that we see in the original photographs of the Farnsworth House. He visited Charles and Ray Eames during the construction of their house in Los Angeles.

When building with 1950’s plastic elements, the house is not meant to be there forever. A stone house, on the other hand, can stand for centuries. A paper house has fragility in its DNA. It will disappear. To accept the condition of temporary existence is interesting, I think. It’s very relaxing. I guess that it is what I like about the summer house in Frösakull. It forces you to question your idea of what a house is. In such a structure you start to act in a less conventional way. You don’t do the obvious. Its undefined open character invites you to try things out. It creates the unexpected. That’s what attracts me to it. I find it healthy and good for the mind.

The house doesn’t have a center. There is no central heating; the definition of where the warmth begins and where it stops is diffuse. The house is somehow everywhere and nowhere. It’s not a house that comforts you with easy associations and predictability. It is for these reasons, that I find the Frösakull house much more interesting and universal than sad or nostalgic.

I have visited nearly all of Mathsson’s other houses, too. I went to see them because I believed that they would help me to understand his work and ideas better (and I also made a film on his row houses in the Swedish town of Kosta). Sometimes I met owners boasting about original chairs and wearing jackets from the fifties. Some people like being controlled by the past, by memories of better times or arbitrary sentiments. This surprises me.

I try to exclude all sentimentality from my work. Even if the motif is sentimental, I don’t want to herald this as a message. I think it’s dangerous.

AND NOW, DID THE SALE OF THE HOUSE CUT ALL POSSIBILITIES OF GOING THERE?

Yes, and it’s a good thing. If I still had the keys, I would go there and take more pictures. At some point, I wanted to stop. At one point the owners even asked if I wanted to buy the house!

I declined, because if I had bought it, I would have become its prisoner. I was so obsessed by it.

WHAT WERE YOU OBSESSED ABOUT?

How to make interesting images.

WHICH IDEAS ARE YOU WORKING WITH RIGHT NOW?

The difference between the perception of the object and the object itself.

In my work, the object itself is less important than the perceptive experiments it allows. However, an image is always a description in some way. You can’t get away from that. Using analogue film, photography is a relief of the world in front of you. But it’s a technical reproduction. A camera is not a machine. It’s an apparatus. Using different lenses, I articulate my ideas on perception and representation, regardless of the object.

It’s not about the material, it’s not about the object, it’s not about the motif. It’s about how you approach it, how you articulate it. Once you understand this as an architect or an artist it changes the way you look at things. When you work as a documentarist, it’s about what’s there. But when you work as an artist, or as an image maker, it’s a combination of facts and imagination, as the author Péter Nádas notes in on | auf, the book I did on the Serpentine Gallery project by Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei. I, so to speak, borrow the buildings to create an “autonomous space”.

I will explore these themes – perception, displacement, liminal spaces – further in a project on Sigurd Lewerentz, which I have been working on since 2000.

05.11.2022

米卡尔-奥尔森: 2000年左右,我进入了布鲁诺-马特松在弗洛萨库尔的夏季别墅,这是他在1960年设计的。我来到这里,进入后才发现,它已经多年没有被人动过了。那里充满了当初的的家具和物品,包括餐具和马特松的私人物件。住宅的某些部分已经退化了;墙壁上长出了真菌,纤维增强复合材料(FRP)的屋顶已经变黄了。尽管大自然开始回收这所住宅,但它的优雅和自然性仍然存在。

起初,我感觉到一种吸引力和排斥力的混合。我无法停止思考这种感觉意味着什么。我决定问问业主,我是否可以拥有这所住宅的钥匙,并启动一个关于它的摄影项目。为了完成这项工作,我觉得我需要在那里待更长的时间,我需要探索这个建筑是如何变化的,它对我有什么影响。

我拿到了钥匙,许多年来,只要我想,我就会去那里。在这段时间里,没有人真正使用这所住宅。我独自在那儿,没有邀请其他人。那是一个探索艺术的地方。在夏天,我去那里的时间更长。在冬天或春天,它变得非常冷;当外面寒冷,里面更冷。你可以从我的一些图片中感受到这一点。里面有一桶桶的水,冻得很结实,甚至在五月初的时候。

这所住宅是对马特松对居住方式的想法的一次全面测试。可移动的墙壁,带轮子的火炉。你实际上在室内和室外都可以做饭。马特松本人有时甚至睡在外面。白天从住宅里向外看时,你可以通过玻璃或波纹板墙看到大自然。

大自然成为一个事情发生的场景。你观察它,可以看到风如何移动树木。到了晚上,情况就相反了。对路过的人来说,房子是一个场景。大自然消失在黑暗中,移动的剪影出现了。它们在客厅里是清晰的,在院子里是模糊的,因为塑料板扭曲了形状,软化了轮廓。

作为一个摄影师,一个艺术家,我对待这所住宅就像一个画家去他的工作室。我去那里是为了潜入并探索图像制作的深度和可能性。引导我的问题是: 建筑如何能在二维图像中得到体现?什么是摄影?

我想做实验。

实验的内容是什么?

在开始的时候,我是相当谨慎的。我布置不同的 "场景",拍摄即时的宝丽来照片,然后把所有东西放回原处。不知怎的,我想有人会回来看它的样子,来检查我在做什么。但一段时间后,我在这所住宅里很有家的感觉,变得更放松了。我甚至开始在那里做饭,使用马特松的餐具。

多年来,我多次重新布置这个空间,以发掘其隐藏的潜力。解构并超越其明显的空间组织。我只是在测试。构思图像,拍照,打印。

这所住宅成了一个试验台。我甚至把天花板的一部分拆下来,以拓展新的空间可能性。在我的书《索德拉库尔客弗洛萨库尔》(Södrakull Frösakull)中,呈现了几个不同的房间。这些图像被融合成一个系列,给人的印象是这所住宅是一个比它大得多的空间。但看一下平面图,你会意识到这是一个小住宅——包含外部的露台,大约10 x 15米。

对我来说,这整段经历是一个完美的机会去质疑建筑图像是什么,或者它可以是什么。我在试验建筑和它的内部如何能帮助我创造吸引观众目光的图像。

你自己的作品在弗罗萨库尔的实验中是如何发展的?

在这个项目中,我探索了不同的表现方式,探索如何展示和表现空间。这就是为什么我现在可以轻松地在委托项目和我自己的艺术项目之间来回转换。这关乎于处理不同类型的表现和想法——现在我知道如何从与客户审美偏好相协调的表现模式切换到我个人参与的模式。

我自己的工作总是涉及到图像、历史和摄影。当我做委托时,我不是一个艺术家。但我用我的艺术知识,以图像的形式加强客户的工作。

一开始,我只是到房子里去拍照。但过了一段时间,我不得不重新启动我的思维,看看我到底看到了什么。我喜欢用4 x 5的模拟相机,用它你工作得非常慢。你的思维会变慢。你开始思考出现在镜头前的东西。你集中精力。所有这一切都导致了观察,并在你的脑海中停留多年。

洞察力的一个常见问题是,它很快变得无意识和肤浅。你需要约束自己,跳出框框看问题。"你不能只见树木不见森林"。你看到一棵树的次数太多,以至于你最终停止了对它的感知。我经常告诉自己要重新开始——让我的头脑感知面前的事物,就像它第一次出现在那里一样。

你的书《索德拉库尔-弗洛萨库尔》展示了两所不同的住宅和接近它们的不同方式。

是的,在索德拉库尔的另一所住宅,是马特松的全职住所。当我第一次访问它时,没有人住在那里。它年久失修,我没有办法进入。我走了一圈,拍了一些偷窥者的照片。

我猜每个人都知道发现一个废弃的住宅并对它的内部情况感兴趣的感觉。你走近,试图用你的眼睛穿透内部。我想把这个时刻转化为照片。这些照片成为这本书的开始——更抽象的图像。

你认为被遗弃的夏季别墅比被遗弃的住宅激起了更深的悲伤感吗?

事情正在发生变化。我对摄影的想法一点也不怀旧。即使马特松的住宅代表了某种怀旧,它也以一种极端和集中的方式代表了深深扎根于现代瑞典社会的想法。马特松是一位重要的设计师。他的想法和喜好在他的项目中得到了明确的表达。他对自然主义、健康、轻盈、空气和阳光非常感兴趣。

马特松去了美国。他遇到了埃德加-考夫曼,MoMA的一位策展人。他被介绍到美国的建筑界。他遇到了密斯-凡-德-罗的客户范斯沃斯夫人。她甚至买了马特森的家具,我们在范斯沃斯宅的原始照片中看到的就是他的家具。在查尔斯和雷-伊姆斯在洛杉矶建造住宅的过程中,他拜访了他们。

当用1950年的塑料元素建造时,住宅并不是要永远存在的。另一方面,石头房子则可以矗立几个世纪。纸房子的基因是脆弱的。它将会消失。接受暂时存在的条件是有趣的,我认为。这是很放松的。我想这就是我喜欢弗洛萨库尔的夏季别墅的原因。它迫使你质疑你对住宅的想法。在这样的结构中,你开始以一种不太传统的方式行事。你不做明显的事情,它未定义的开放特性邀请你去尝试,它创造了意想不到的东西。这就是它吸引我的地方。我发现它是健康的,对心灵有好处。

这所住宅没有一个中心。没有中央供暖;温暖的开始和停止的定义是分散的。这所住宅不知何故无处不在,也无处不有。它不是一个能用简单的联想和可预测性来取悦你的住宅。正是由于这些原因,我发现弗洛萨库尔宅比悲伤或怀旧更有趣和普遍。

我也几乎参观了马特松的所有其他住宅。我去看他们,因为我相信他们会帮助我更好地理解他的作品和想法(我还拍了一部关于他在瑞典科斯塔镇的排屋的电影)。有时我遇到业主吹嘘他们原始的椅子,穿着50年代的夹克。有些人喜欢被过去控制,被对美好时代的回忆或任意的情绪控制。这让我感到惊讶。

我试图在我的作品中排除所有的感伤。即使主题是多愁善感的,我也不想把它作为一个信息来预示。我认为这很危险。

而现在,住宅的出售切断了去那里的所有可能性吗?

是的,这是件好事。如果我还有钥匙,我会去那里,拍更多照片。在某些时候,我想停下来。有一次,业主甚至问我是否想买下这所住宅!

我拒绝了,因为如果我买了它,我就会成为它的俘虏。我对它是如此痴迷。

你迷恋的是什么?

如何制作有趣的图像。

你现在正在研究哪些想法?

对物体的感知和物体本身之间的区别。

在我的作品中,物体本身没有那么重要,而是它所允许的感知实验。然而,图像总是在某种程度上是一种描述。你无法摆脱这一点。使用模拟胶片,摄影是对你面前的世界的一种慰藉,但这是一种技术性的再现。相机不是一台机器。它是一种仪器。使用不同的镜头,我阐明了我对感知和代表的想法,不管对象是什么。

它不关乎于材料,它不关乎于对象,它不关乎于主题。它关乎于你如何接近它,你如何表达它。一旦你作为一个建筑师或艺术家理解了这一点,就会改变你看问题的方式。当你作为一个记录者工作时,它是关于那里的东西。但当你作为一个艺术家,或作为一个图像制作者工作时,它是事实和想象力的结合,正如作者彼得-纳达斯(Péter Nádas)在《奥夫》一书中所指出的,我为赫尔佐格和德梅隆和艾未未的蛇形画廊项目所做的书。可以这么说,我借用建筑来创造一个 "自主空间"。

我将进一步探索这些主题——感知、流离失所、边缘空间——在一个西格德-卢埃伦茨的项目中,我从2000年开始就在做这件事了。

2022年11月5日

Mikael Olsson

Mikael Olsson is an artist and photographer, trained at the Department of Photography and Film at the University of Gothenburg 1993-96. His book projects include Södrakull Frösakull (Steidl, 2011), on | auf (Steidl, 2020), Olsson Mikael (Art and Theory, 2022), LWRNTZ [work in progress] (with Jan-Erik Lundström, Andersson Örn, 2022). He has had solo exhibitions at Hasselblad Center in Gothenburg (2009) and Columbia University in New York (2011). In 2018, Olsson and the architect Petra Gipp presented a work on Lewerentz in the main exhibition of the Venice Biennale of Architecture. Olsson has also acted in films such as Ruben Östlund’s The Square, Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria and British artist and director Isaac Julien’s Lessons of the Hour. He is represented by Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm/Berlin/Mexico City.

Mikael Olsson

Mikael Olsson is an artist and photographer, trained at the Department of Photography and Film at the University of Gothenburg 1993-96. His book projects include Södrakull Frösakull (Steidl, 2011), on | auf (Steidl, 2020), Olsson Mikael (Art and Theory, 2022), LWRNTZ [work in progress] (with Jan-Erik Lundström, Andersson Örn, 2022). He has had solo exhibitions at Hasselblad Center in Gothenburg (2009) and Columbia University in New York (2011). In 2018, Olsson and the architect Petra Gipp presented a work on Lewerentz in the main exhibition of the Venice Biennale of Architecture. Olsson has also acted in films such as Ruben Östlund’s The Square, Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria and British artist and director Isaac Julien’s Lessons of the Hour. He is represented by Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm/Berlin/Mexico City.

Mikael Olsson

Mikael Olsson is an artist and photographer, trained at the Department of Photography and Film at the University of Gothenburg 1993-96. His book projects include Södrakull Frösakull (Steidl, 2011), on | auf (Steidl, 2020), Olsson Mikael (Art and Theory, 2022), LWRNTZ [work in progress] (with Jan-Erik Lundström, Andersson Örn, 2022). He has had solo exhibitions at Hasselblad Center in Gothenburg (2009) and Columbia University in New York (2011). In 2018, Olsson and the architect Petra Gipp presented a work on Lewerentz in the main exhibition of the Venice Biennale of Architecture. Olsson has also acted in films such as Ruben Östlund’s The Square, Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria and British artist and director Isaac Julien’s Lessons of the Hour. He is represented by Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm/Berlin/Mexico City.