エリカ・オーフェルメール: 家や住まいというものは、意味の広い概念ですよね。ですから、住宅として何を選ぶかよりも、まずは自分自身に問いを投げかける必要がありました。住むとはどういうことなのだろうか?私はどうやって生きるのだろうか?どのようにして社会が建築を形づくるのだろうか?こういった問いへの探求が、私に考えさせる時間をくれました。自分の家や、かつて訪れたことのある家、本やインターネットで見たことのある家などを見てみることにしました。

何を評価基準とされたのですか?

私は、都市空間を形成する社会構造と、そこで生じる自然環境との関係に常に興味を持っていました。また、時代と共に、洞窟の中の火が住居の中へと移動し、そして、住居の中から都市の中へと移動していったことを考えたのです。

もともと暖炉というものは、人の集まる装置でした。食料を交換し、蓄える場所として。心地良い避難所として。それに遊び場として。社会的慣習もそうやって人が集まることで発展したものです。産業革命以前のキッチンとは、火のある部屋のことであり、みんな仕事終わりにはそこでほとんどの時間を過ごしたのです。

19世紀は、ソーシャルハウジングが産業のビジネスへと変化し始めた時期です。その新しいタイポロジーは、家がどうあるべきかを明確に固定してしまうようなものでした。どういうわけか、機能は独立した小さな部屋に分割され、そのうちの一つに蛇口がつけられました。そこがスカラリーと呼ばれたのです。そうして、スカラリーは純粋に機能的なキッチンとなりました。その瞬間に「火のある部屋」は、社交のための場ではなくなりました。かつては、フレキシブルな家の中心として、複合的で機能的な部屋だったのですよ。

産業社会によって、キッチンに人が集まることはなくなりました。キッチンは監禁の場所、つまり分離と隔離の空間となりました。特に女性にとってはね。

そのことは、私たちのよく知る多くの戸建てや集合住宅において、今でも揺るぎない基準となっています。私たちの住まいが、ヒエラルキーで組織化された家であるとは、誰も思いません。ですが、実際は依然としてそういったものが残っているのです。とても単純で疑問の余地もないような考えが、実は、家庭空間のあり方を支配している。少なくとも私にはそう思えるのです。

このインタビューへの誘いを受けて、凝り固まった紋切り型の機能主義に対するオルタナティブとして、流動的な空間のコンセプトをもった住まいを探し始めました。

アルベルト・カラチのラ・プラタネラを選ばれたのはなぜですか?

最初は、会話のトピックとしてリナ・ボ・バルディのバルディ邸を選ぼうと思っていました。特に女性の話を持ち込むにはいいだろうと。その建物のイメージが、私の頭の中には何年もの間残っていたのです。ついに訪れることはなかったのですが。ところが、平面図をよく見てみると、実はかなりヒエラルキーの組織化された住宅だと気づきました。とても明解に作られています。召使いの住む場所があり、独立したキッチンがあり、その他にも分割された空間があり、そしてディスプレイとしてのメインスペースがある。つまり表現としての空間です。とても好きなプロジェクトですよ。リナ・ボ・バルディの作品はどれも大好きですし。ですが、社会的、あるいは空間的な視点から見るとこの住宅には、伝統的なヒエラルキーがそのまま強く残っているんです。こんな特別なシチュエーションの中では、ブラジルの亜熱帯植物にすぐに目がいってしまいますよね。森の中に吊り下げられたリビングルーム。素晴らしい家具たちの美しいまとまり。大きな窓に青々とした外の緑。ただ、これらは私の話したかった内容とは関係のないことです。

その後、私のよく知るアルノ・ブランドフーバーの住宅と、その空間に着目してみました。彼とは10年以上の付き合いですし、彼のほとんどの作品を写真に撮ってきました。それらの建物は、どこから始まってどこで終わっているかが、よくわからない感じで好きなんです。スタジオやギャラリーも住居の一部のようになっていて、不可解な形で溶け合っています。

これらは、言ってみれば、多様な用途に開かれた住居ということなのでしょうか。彼の自邸において特に顕著なことですが、時間帯の変化や、場所による寒暖の変化、日常あるいは季節的な変化、そして個人の気持ちの変化など、いろいろ変化によって空間の使い方が変わっているのです。この流動性はとても面白いですね。例えば、ベルリンのブルネン通りにある大きな住宅は、地上階と2階にギャラリーがあるのですが、私が訪れた時、アルノの事務所は3階にあって、4階と5階は彼のプライベートスペースとして、彼の友人やゲストなどの様々な人と過ごすことのできる空間になっていました。

あらゆる機能と目的とが入れ替え可能になっています。そういった形の都市の住宅は見たことがありませんでした。二ヶ月後には、あらゆるものが違う場所に配置されていることもあり得ます。同じ場所にあり続けるのは、ストーブだけ。キッチンでさえキッチンらしい設えがなく、移動可能な空間になっています。

彼の建築には、自然と文化との境目がなく、その内部空間の作る曖昧さは素晴らしいと思います。今日の建築的議論の中では、あまり取り上げられていないようなことだとは思いますが。内部空間がどうあるべきかについて、みんなそんなに疑問を持つことはないのでしょう。ですが、私は逆にもっと議論すべきなのだと思いますし、いろんな取り組みがなされるべきだと思います。それは風土とは、関係のないことだと思います。

あなた方からのインタビュー依頼を受けて、私は、こういったことに興味を持ち、探求していたのだという事が改めて明確になってきました。

住宅内での監禁的状態、機能や用途の分離、決まりきった組織化の方法。そういったことに対する、用途の自由さ、空間の流動性や回遊性、そして自由度。内部と外部、文化と自然、秩序と直感との関係性。これらは、私が考えてきたことです。

そして、結局いつも同じ住宅のことを考えていたのだと気づきました。メキシコシティにあるアルベルト・カラチのラ・プラタネラです。

そこには、行かれたことがあるのですか?

そこへ初めて行った時は、自分がどこへ向かっているのかもわからないような状態でした。ただ、連れられて。メキシコシティの、とりわけ特徴のない普通の住宅街にある小さな脇道を抜けて行きました。あるところで、ドアの前に到着したことを覚えています。のっぺりとした、なんてことはない壁面につけられたドア。そこを開けると、すぐに庭の中に入っていることに気づきました。しかも、そこがリビングでもあったのです。私はどこにいるのだろうか、と考えざるを得ませんでした。歩き出すとすぐに、ある領域に入ったのがわかりました。突然、大きな熱帯植物の間から毛皮のハンモックや柔らかなソファが見えてきました。それらは、黒の火山石の敷き詰められた中庭に置かれていました。庭の中は、所々に影が作られ、屋根のかかっているところもありました。そこは外部空間でもあり同時に内部空間でもあるような場所でした。

あらゆるものが寛大で、そしてラグジュアリーに見えました。ところが、素材やディテールはすごくシンプルなのです。キッチンにはオーナーのお父さんがいました。とても高齢の方でしたが、そこでお茶を入れていました。その横の部屋では誰かが座って書き物をしていて、また別のコーナーではガヤガヤと雑談している人たちがいました。とてもウェルカムで開けた家でした。友達や親族、あるいは家族が勝手にやってきて、また出ていくというような、大きなソーシャルネットワークの一部のような場所だと感じられました。

メキシコシティでの人々の社会的な振る舞い方が、とても好きだったことを思い出します。パブリックスペースとプライベートスペースが入れ替わるような振る舞い方です。人と一緒に空間を共有する際のコミュニティが持つ相互扶助的な考え方が、とても興味深いのです。

気候がそうさせるのかもしれませんが、それが典型的なこの社会の組織化の方法であることは間違いありません。そういった点から考えると、ラ・プラタネラの空間は理解しやすいでしょう。誰が作ったとか、どの時代だとかは関係なく、この空間構成は、私にとってはとても印象深いものでした。ただクールで、気取りのない空間構成。メインスペースは、自然と文化との中間にあるような空間に感じられましたし、周辺環境や空間の使われ方、そしてそこにいる人々との有機的な関係性は、とても民主的なものでした。

インターネットで見られるこの住宅の写真についてはどう思われますか?そこに、経験されたようなことは表現されているのでしょうか?

ウェブサイトにある写真では、私がそこで感じたようなことは伝えられていないと思います。私が見てきた多くの写真家は、空間の構成を俯瞰して捉えることができないのだと思います。あるいは、興味がないのでしょう。ですから、大抵はディテールや形式的な側面に焦点が当てられています。本当は、それらが統合されるべきなのだと思いますが。この家のオーナーであり、ギャラリストである方へのロングインタビューの記事を見つけました。そこで、この家の起源が語られていました。もともとは修道院だったそうです。ラ・プラタネラは、その既存の歴史的な壁の上に新しく作られたのだと。この自由な感じはそこから生まれているのだと思います。歴史のレイヤーが積み重なっている、ということですね。

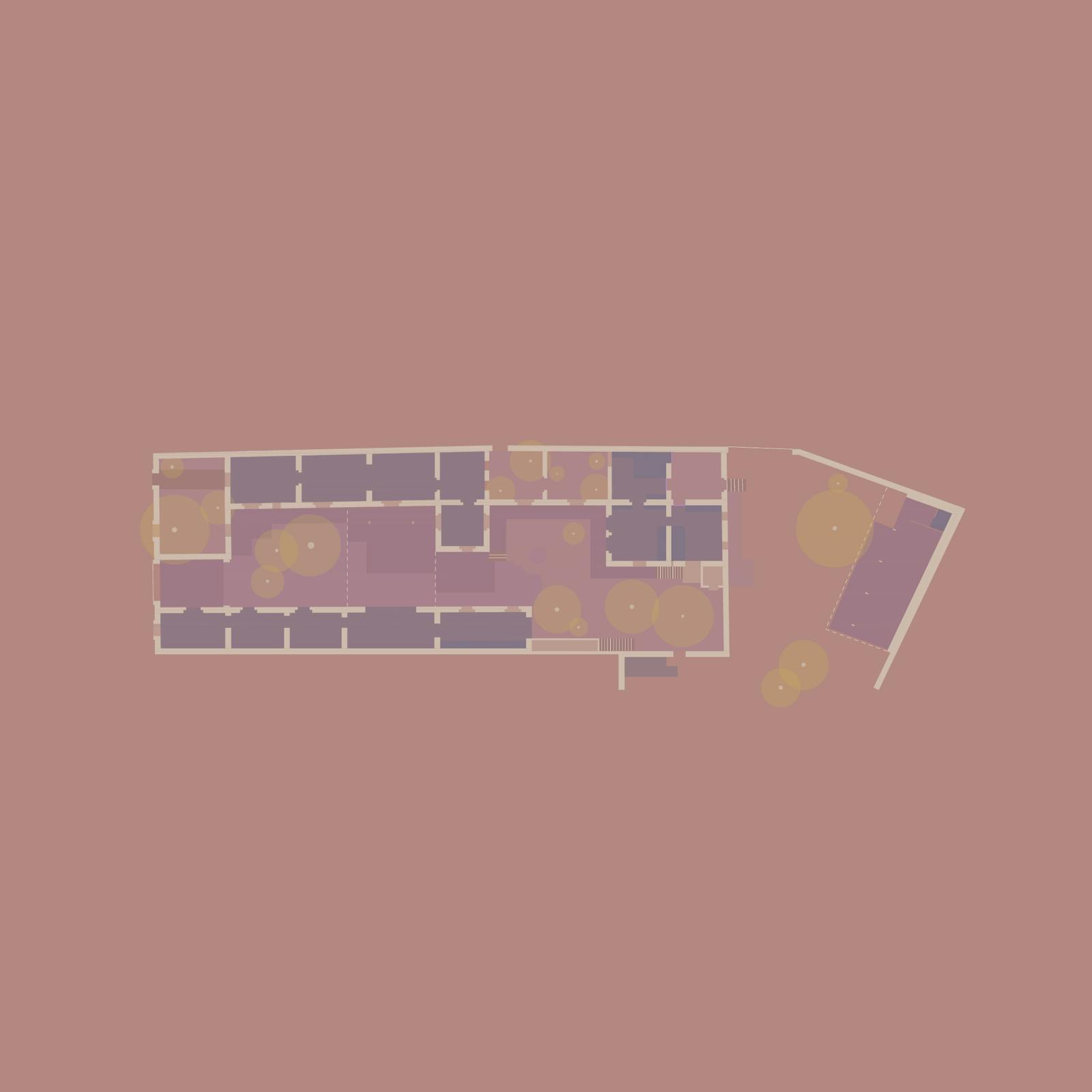

この住宅は、既存の建築を適度に受け入ながら利用しています。周囲の壁面に沿って、小さなユニットが緩やかに中庭を囲っていますね。中に入ると、そのことがすぐにわかると思います。一つはキッチンとして使われていて、その他はダイニングルームや、読書室などに使われています。全てが中庭に向かって開いています。庭の奥には、ここで唯一の全く新しく作られた空間があるのです。それはプラタナスの木に隠されています。プラタナスの木は、このプロジェクトの名前の由来となっていますね。ここがオーナーのプライベート空間になっていて、ここで寝たりするのでしょう。つまり、今議論しているこの住宅は、実は紛れもなく、内向的な性質をもっているということです。

顔がなく、のっぺりとした巨大な壁の後ろにあるのは、内部の自由さと、公共の目からは全く閉ざされた世界、というわけです。

入った時に感じる驚きが、最も印象に残っていることでしょうか?

驚きということよりは、アルベルト・カラチもクライアントも表現ということに対してあまり興味がなさそうな事が、とても印象的でした。このファサードなんて都市の中でも全く無表情なものです。何かの社会的側面が、こういった特定の人々をインビジブルなものへと向かせるのでしょうか。あるいは、それがここでの建物の文化、つまりプライベートな空間とパブリックな空間との関係性における特徴なのかもしれません。建築家やオーナーは、ステータスの象徴としてのオブジェを作ったり、それをひけらかすようなことを控えている。その心理的な側面にも興味を持ちました。この住宅はそういったこととは真逆で、ステートメントやアイコンとして作られているわけではない。そのことが逆に強烈な個性となっています。周囲に完全に溶け込んでいますね。

この住宅はなんのためにあるのでしょうか?

私たちの知っているような、ほとんど全ての建築プロジェクトは、表現の問題と関わっています。つまり、世界に対して何を表現するのか、ということです。ラ・プラタネラはこういった表現の問題を完全にスキップしていて、つまり純粋に、住まいであるということです。そして社会的空間である。建築家は、無駄なことなど言わず、本当に美しい住宅を作ったのです。

内部と外部、そしてその二つの曖昧さ。さまざまなタイプの外部空間。植物の置かれた内部空間。部屋としての庭。庭としての部屋。美しいでしょう。植物は育ってきますから、手入れをしなくてはいけません。だからこそ愛おしく思える。植物との関係性はさまざまですが、これら全ての豊かさは、内面化された世界においてひっそりと育まれるものです。都市には背を向けたまま。

自然によって廃墟化することで、生き生きとしてくるといったことも考えられますか?

そういったことも考えていました。とてもメキシコ的な特徴だと思います。つまり、ここではエントロピーの考え方が特徴的で、来ているのか去っているのか、増えているのか減っていっているのか、そういったことがもはやわからなくなる。このエントロピーの不明瞭さが、とても面白い。それがメキシコ的空間のリアリティなのだと思います。

今朝もバラガンとカラチの違いを考えていました。この二人の世代的な違いを見てみるのも面白いと思います。二人ともメキシコシティで作っていますよね。バラガンは裕福な家庭で生まれ、田舎で育ちました。馬にも乗っていたのでしょう。ランドスケープや植物などのこともよく知っていました。後にメキシコシティの南部にある火山地帯のマスタープランを計画していましたね。火山と自然のランドスケープとの関係がよく考えられたものでした。

ところが、彼の後期の作品では、庭、つまり自然の存在が小さくなっていきます。自然は、ほとんど瞑想のための対象物となってしまいました。人間は自然の一部ではなく、それを観察し賞賛する遠く離れた存在である、という二元論的な考えが見て取れます。文化的なのです。魅力的な内部空間のシークエンスがあり、自然がある。でもそれは、外部としての自然だということです。彼の自邸、バラガン邸ではそのことが顕著に見て取れます。自然環境はとても重要な役割を果たしてはいますが、自制すべきものとして扱われているのです。巨大な窓のあるメインルームからは、自然を見ることはできますが、外へ出ることはできません。庭へ出るには、メインルームの脇にある小さな部屋の、さらに小さなドアから出ていくのです。必要となれば、庭へは出ることができる。ところが、基本的には、庭は外にあるべきだということです。彼がなぜそうしたのかわかりません。とても窮屈に感じますし、極度にコントロールされていて、堅苦しく拘束的な感じがします。

こうした支配と分離といった感覚は、現在の哲学においても未だ根強い感覚だと思います。しかし、それを維持することはもはや不可能で、機能するものではないと思います。私たちは、物事を全体として見るべきなのだと思います。全ては繋がっているのだと。こういった熱帯的直感が、カラチのラ・プラタネラには表れていますね。

メキシコシティでは、鉢や花壇から育つ植物と、道から自生する植物との間には、ほとんど違いが見られません。全てが絡み合っている。これは、いろいろなことへ応用できる考え方だと思います。支配的な考えとは全く異なるものですよね。今でも二元論的な考え方は、私たちの文化や社会のあらゆるところに浸透していますが、このカラチの住宅では、その二元論的な考え方がさまざまな方法で解決されてるのです。民主的ですよ。いろいろな意味でね。

新旧の関係が重要だということでしょうか?

そうだとも言えますが、関係ないときもありますね。コンテクストによるでしょう。建築家やプロジェクトの開発者の多くは、わかりやすく計画されたタブラ・ラーサに興味を持つようですが。私は、土着的な、あるいは控えめな建築の方に興味がありますね。自然な形で階層化された複雑さを持っていて、用途に多義性をもった建築です。それには、高い次元での知性が必要だと思います。それは、空間的なヒエラルキーを作るということではないですよ。以前からあったものと新しくできたもの、その違いが明瞭に示せないことこそが重要なのだと思います。全てが過程であって、新しいものは何もないのだと。何かから始まって、それに答えて、その次がまたやって来て、というような形で、社会的にも空間的に全てが繋がっているのです。時には、フレッシュで本当に新しいものが必要とされる時もあると思いますが。ラ・プラタネラは知的なディスコースでもエクササイズでもありませんね。実利的で有機的なものです。

私が写真を見た印象からは、素材やディテールの選択が極めて明快で、新旧の区別もすぐにわかったくらいです。私が変なのでしょうか?

おそらく写真のせいだとは思いますが、行ってみてください。新旧の区別は難しいと思います。でもそんなことはどうでも良いでしょう。最初に目につくのは、ディテールではないと思います。そうですね。少なくとも私にとっては、内部と外部の表現によって生まれる曖昧な領域には、目眩を覚えました。

標高の高さから生じる鈍く柔らかな音、鳥のさえずり、通りから聞こえる遠くの声、通り過ぎる車、さらさらと優しく揺れ動く葉の影、太陽光の素晴らしさ、そのトーン、小さなそよ風、それら全てが浸透しあって、空間の経験を形成しています。こういったことは、写真だけが仄めかすことのできる感覚です。

建築に携わる写真家として、ご自身の専門分野に対しては、どのようなことをお考えですか?

極端に言えば、分野といっても砂漠みたいなものですよ。ほとんどの写真家は、事や物に集中して、美的で形式的な側面に多くの焦点を当てています。そして、プロジェクトはそのコンテクストや周囲の環境から意図的に隔離されてしまっています。広告目的で作られ、わかりやすさが賞賛される環境の中で、容易に消費されてしまうイメージたち。そういった写真のことではないのです。

写真には、矛盾や複雑さ、曖昧さや多様性、そして不確かさを維持する力があると考えています。それは、ダイアローグとディスコースの形式ということでしょうか。少なくとも、私の興味はそこにあります。私は、私の見ているものに対して曖昧でありたいと思っていますし、相反的で両義的なシチュエーションに対して真っ向から取り組みたいと思っています。そういったことを思っていると、どうしても建築が関係してきます。それこそが建築であるということではないですが。

どのようにして、こういった認識に到達されたのですか?

言葉にする前から、わかっていたのだと思います。私は、空間の一貫性や空間の体験といったものに興味を持っていました。それがどんなものであるのか、何が表現されているのか、は関係ありません。私たちが世界の中にいる、というとても広い意味での興味です。

私が美大のスタジオ課題に取り組み始めたときのことです。スタジオでは空間的なアプローチに対する、代替としてのナラティブに関心が向けられていました。当時は、AAスクールがしていたことをよく見ていました。とても実験的なものでした。

課題としての実施要綱はないはずです。でも実際にはあるも同然だったのです。機能しなくてはいけないですから。「設計」しなくてはいけなかったですし、それが機能するための基準もありました。私は、機能だけではない何かが、空間にはあるのだと感じていました。私にとってそれは、社会であり、空間的で感情的な経験のことでした。どうすれば、そのことを議論できるのか考えていました。

私は、リートフェルトアカデミーの学生として、ジャック・ヘルツォークをパブリックカンファレンスに招待しました。彼は来てくれて、話をしてくれました。道が開けた感じがしました。彼の言っていたことがとても面白かったのです。当時、私は、どこへ向かえばいいのかわかっていませんでした。そんな時に「卒業したら、うちに来てよ」とジャックが誘ってくれたのです。私のしてきたことは、基本的にはそれだけです。私が、ヘルツォーク&ド・ムーロンで働いた初めての外国人だったと思います。ところが、私のそれまでの経験や興味だけでは、スイスの建築実務の厳しさや現実を受け入れる準備ができていませんでした。建てる方法がわからなかったのです。深刻な問題でした。技術的なことは何一つわからなかったのですが、何か面白いことが起きているということだけは感じられました。全ての点を結びつけるには、しばらく時間がかかりましたが、こうして、建物を建てずとも、自分の言葉で議論に参加できるメディアとして写真を発見できたのです。

こういった経験を通して、コミュニケーションや仕事をする方法を模索しつつも、私は私の道を切り開いていきました。考えてみれば、建築の中に限らず、空間の中や、私たちのこうした経験の中では、もっともっといろんな事が起きています。なのに、なぜ私たちは建築のことだけを話しているのでしょう?建築は会話の一部であり、それが全てではないでしょう。

2022年7月28日

Erica Overmeer: A house or a dwelling are very broad notions. I felt, that before making a choice, I needed to confront myself with questions like: What is it to dwell, how do I live? How does society shape what we are building today? The time spent exploring these questions, got me thinking in ways that I had not tried before. I looked at my own house, the houses I had visited, the houses I knew only from books or the Internet.

WHAT WERE YOUR CRITERIA?

I have always been interested in the relationship between the social structures that define urban spaces and the natural settings where they appear. I also thought about how over time the fire moved from a cave to a dwelling, from a house to a city.

Since the beginning a fireplace has been instrumental in gathering people, in the exchange and preparation of food, comfort, shelter, play, and the social customs that developed out of being together. Before the industrial revolution the kitchen - the room with the fire, was the space where the majority of people spent most of their time after the work was done.

In the 19th century, in the moment when social housing started to be an industrial business, a new typology crystallised and consolidated on how a house should be organised. It somehow emerged that functions should be divided between a series of small separate rooms and one of them would have a water tap - and be called a scullery. The scullery in turn became a purely functional kitchen and in this very moment „the room with the fire” stopped being a social place, a plural, functional, flexible central room. Industrial society removed the meeting of individuals from the kitchen. It became a place of confinement. It became a place of separation and segregation, especially for women.

It still constitutes an unchallenged standard for the majority of houses and apartments we know. We tend to think we no longer live in hierarchically organised houses. However, this model still persists and, it seems to me at least, that a very simple minded, unquestioned idea still dominates how domestic spaces are organised.

When you invited me, I started to look for dwellings that proposed an alternative to a fixed, functionalist cliché and acknowledged a more fluid concept of space.

HOW DID YOU END UP CHOOSING THE ALBERTO KALACH’S LA PLATANERA HOUSE?

At first, for the topic of our conversation I wanted to choose Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro, notably also to bring a female position to the conversation. Over the years, many images of the building had stayed with me, but I had also never visited the house in person. After further examination of the floor plans I realised that it is actually a very hierarchically organised house. It is very clear, there’s a place where the servants live, a separate kitchen, other segregated spaces and then the main space of display, of representation. Although I really love this project – and I love the work of Lina Bo Bardi in general – I had the feeling that from a social and spatial point of view, traditional hierarchies where still very much intact in this house. You can easily be distracted by the sub tropical vegetation of Brazil notably in this specific situation; the images of the elevated living room suspended in the forest, the beautiful configuration of the amazing furniture, the big windows with the lush vegetation outside. In truth, this was not going to work as an example for what I wanted to talk about.

After that, I concentrated on the houses of Arno Brandlhuber, spaces that I know well. I’ve been working with him for the last ten years and I have photographed most of his work. What I like about these buildings is that you cannot say where the house stops and something else starts, a studio or a gallery seems to be a part of an apartment, they melt together inexplicably.

These are houses, if this is how we should call them, that are very open to diverse modes of use. It is especially true in the buildings he built for himself, there’s a very interesting fluidity in the way one uses the space depending on the time of day, where it’s warm, or cold, and following daily, seasonal and personal fluctuations. Brunnenstrasse in Berlin, for instance is a large house with a gallery on the ground and first floor. When I first visited, Arno’s office was on the second floor, and on the third and fourth floor there were his private spaces or spaces he shared at different times with different people, friends, guests, etc.

I remember a kind of exchange between all the programs and purposes, that I had never seen before in a city house. You could come two months later, and everything would be in a different place. The only thing that remained constant was the stove. Even the kitchen was a kind of a transitional space without a clear kitchen-like character.

Even though in his architecture there are no blurred borders between nature and culture, I very much appreciate the ambiguity in the way the interior spaces are organised. It seems to me something that it is hardly addressed in architectural discourse today. Everybody more or less agrees on what kind of internal organisation we need. I counter this and believe instead, that there is a lot to be discussed and a lot to be done in this field, regardless of climatic conditions.

All these examples made clear the topics I am interested in and had searched for when you first wrote to me.

I was thinking about confinement, separation of functions and use in a house, predefined organisation, freedom of use, fluidity, circulation, freedom in a space and the relation between inside and outside, culture and nature, ordered and intuitive.

In the end I realised that I was constantly coming back to one house. This journey brought me to La Platanera by Alberto Kalach in Mexico City.

HAVE YOU BEEN TO THE HOUSE?

The first time I went there, I didn’t even know where I was going. People just tugged me along. We were in Mexico City, we passed through many anonymous, small side streets in an otherwise unremarkable and ordinary residential area. At some point I just remember coming to a door in a plain unassuming wall, which we opened, and entered directly into a garden, which was a living room. I really had to make sense of where I was. A second before I walked down the street, and suddenly after passing the threshold I saw a fur hammock and a soft sofa in a courtyard paved with black volcanic stone between large tropical plants. Some parts of the garden where shaded and had a roof. It was an outdoor space that was an interior space at the same time.

Everything was generous and looked very luxurious, but it was very simple in both material and detail. There was the father of the owner in the kitchen, an elderly man, making a tea. In the next room someone was sitting and writing. In another corner, there were some people chit-chatting very informally. It felt like a welcoming open house where people, related friends, or family, could just come and go; it felt like part of a larger social network.

I remember I liked the way people behaved socially in Mexico City - how public spaces become private spaces and vice versa. There’s a very interesting reciprocal idea of community, about being together, and using the space together.

It might be motivated or informed by the climate – but it definitely is a very typical form of social organisation. It finds its explicit expression in how the spaces of La Platanera are made. This spatial configuration stayed in my mind without thinking much about the architect or the period when it was built. It was just a really cool and unpretentious way to organise space. I felt the main space was somewhere between nature and culture. It was very democratic, in regard to the organic relation to its surroundings, to its use and to people being there.

WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE PICTURES OF THE HOUSE AVAILABLE ON THE INTERNET? DO THEY RENDER CORRECTLY THE FEELING YOU EXPERIENCED?

I think that the pictures on the website are not conveying the feeling I had when I was there. From what I observe most photographers seem not to be interested in, or unable to recognise larger spatial constellations, and seem mostly content focussing on some details or formal aspects – hoping it will all come together. I found a long interview, with the owners, gallerists, who spoke about the origins of this space. It had originally been part of a convent. La Platanera is structured on preexisting historic walls, which I think gives it a certain freedom. It’s layered.

Kalach’s house randomly uses and accepts the existing architecture. It’s loosely organised around a courtyard and by small units that are more or less connected following the perimeter wall, all of which you see immediately upon entering. One of them is used as a kitchen, another as a dining room, another as a reading room, etc. all opened and oriented towards the courtyard. The only entirely new space is the one at the back of the garden – behind the Platana trees that also give the project its name. This is where the owners have their more private areas, where they sleep I assume. All this means the house that we discuss today is without question introverted, its faceless and hidden behind a plain and unremarkable large wall. It’s very free inside, but it is also, without doubt, closes away from public view.

WAS THE SURPRISE EFFECT THE MOST STRIKING SENSATION UPON ENTERING?

I think it’s not so much about the surprise. What struck me more was the fact that neither Alberto Kalach nor the clients seemed to care about representation. In context, it has a completely unrepresentative facade. There might be some social aspects that push certain people to look for invisibility. It is also characteristic for the local building culture, an aspect of the relation of private and public spaces. At the time, I thought it was very interesting from a psychological point of view, for an architect and an owner, to refrain from making an object, a show, a symbol of status. As far as I am concerned, it is a very powerful feature of this house. It is not made as a statement, as an icon, it is the complete opposite of all these things. It blends in completely.

WHAT IS THIS HOUSE FOR?

Almost every single architecture project that we know about is concerned with the topic of representation - how it looks and what it represents to the world. La Platanera completely skips this topic. It is purely about dwelling - a social space. This is an architect who really makes a beautiful, iconic house without making any fuss about it.

It’s a house about indoor and outdoor space and about the ambiguity between both. There are different types of outdoor spaces. Some rooms also have plants inside. You have gardens that are rooms and you have rooms that are gardens. Beautiful. You are there, the plants grow around you, you must take care of them, and it’s also why you love them so much. There are relations going on on many levels. All this richness happens quietly in an internalised world that has no formal representation towards the city.

IS THERE AN IDEA OF A RUIN BEING RECLAIMED BY NATURE?

There’s another thing that comes to my mind, which I also think is very characteristic of Mexico. Namely, the idea of entropy, the state when it’s no longer clear whether something is coming or leaving, emerging or diminishing. This entropic ambiguity is for me an extremely fascinating part of Mexican spatial reality.

I thought this morning also about a comparison between Barragàn and Kalach. It’s interesting to observe the generational shift between the two, both of whom built in Mexico City. Barragàn came from a very rich family, growing up in the countryside, riding horses, knowing about landscape, plants etc. and later in life developing masterplans for the volcanic South of Mexico City, explicitly working with the natural and volcanic landscape of this area.

However in his later work, the gardens, the presence of nature, are reduced, almost always, to objects of contemplation. There is a dualistic idea of humans being distant and admiring observers of nature, rather than being part of it. There is a culture - an alluring sequence of interior spaces, and then nature - an exterior. It is especially evident in his own house, Casa Barragàn. The natural surroundings are very important, but they are something to be contained. You have the main room with a huge window, you can look at the nature, but you cannot go out. There is a small room next to the main room and it has a really small door to the garden. You can enter the garden if you need to, but the garden must remain something that’s out there. I don’t know why he did this. But it all felt very uneasy, extremely controlled and formally restrained.

This sense of control and separation is something still very present in the philosophy of today, but it’s no longer possible to sustain, it doesn’t work any longer. We need to think and look at things as an entirety. Everything is connected. This tropical intuition is very present in La Platanera of Kalach. In Mexico City, there is generally very little difference between a plant that grows in the pot and a plant that grows in a flower bed and the vegetation that grows wild in the street. It’s all intertwined. This could apply to many things but it is definitely not about control. Yet, these dualities seem to permeate every aspect of our culture and society. In Kalach’s house, this duality is resolved in many ways. It is a very democratic space, in many ways.

IS THE RELATION BETWEEN OLD AND NEW IMPORTANT?

Sometimes yes, sometimes it doesn’t matter. It all depends on the context. Yet architects and project developers seem still mostly interested in a perceived or planned tabula rasa. I am actually more interested in vernacular architecture, or non-assuming architecture, a naturally layered complexity and ambiguity of use. I feel it requires an intelligence of a higher order, which is definitely not about establishing spatial hierarchies. A very important aspect is that you cannot articulate the difference between what was there before and what came after, because everything is a process and nothing is really new. It’s more like what comes first, how we react to it, and what the next layers are, socially, spatially, and how all this is all connected. And yet, sometimes something fresh and new is exactly what is needed. La Platanera doesn’t feel like an intellectual discourse or exercise, it’s just very practical and organic.

The impression I get from looking at the pictures, is that the choice of the materials and detailing is quite clear, it’s easy to see what is new and what was there before. Am I wrong?

I think this is partly due to the kind of pictures that exist. When you go there, you’re not sure. And it doesn’t matter. The details are not the first thing you notice. Well, at least for me, the first thing that completely put me out of balance was the ambiguity created by the delineation of interior and exterior, inside and outside.

Everything is permeated by the soft sounds muffled by the altitude, birds, distant voices from the street, vehicles passing, the rustling and softly moving shadows of the leaves, the tone and quality of sunlight, a small breeze – all inform the spatial experience. These are sensations that photography can only hint at.

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER WORKING WITH ARCHITECTURE, WHAT IS YOUR POINT OF VIEW ON YOUR FIELD?

To put it in the extreme, it doesn’t feel like a field but more like a desert. It seems to me that most photographers seem to concentrate on things or objects, intently focusing on aesthetic or formal aspects, with the project purposely isolated from its context and surroundings. Images produced for marketing purposes and easy consumption in a context that prizes easy legibility. But that’s not what this is about.

I think that photography has the capacity to hold contradiction, complexity, ambiguity, diversity, and uncertainty – as a form of dialogue and discourse. Or at least that is what I’m interested in. I want to be ambiguous about what I’m looking at — or work directly with ambivalent and ambiguous situations. This eventually, at some point, has to do with architecture but it is not about architecture.

HOW DID YOU ARRIVE TO THIS AWARENESS?

I always knew, even before I could put it in words, that I was interested in spatial coherence and how we experience space, whatever that is or however it is manifested – in the largest sense of our being in the world.

I started out in an art school studio that was quite interested and concerned with alternative narratives of spatial approaches. We were looking a lot at what the AA was doing at the time, it was very experimental. There was no protocol and at the same time there was indeed a protocol. It had to function. You needed to ‘design’, and there were criteria to make it work. I always felt, there was also something else in space that was not only about function. For me it was about a social, spatial and even emotional experience. I wanted to find out how we could talk about that.

As a student at the Rietveld Academy I invited Jacques Herzog to a public conference. Jacques came, and he talked. I thought, well, maybe there is a way. He was saying very interesting things. At the time I didn’t know where to look. Jacques was also kind of inviting, saying: „come to us, when you graduate”. And that is basically what I did. I think I was the first foreign person working in Herzog&de Meuron ever. But my background and interests hardly prepared me for the reality and rigour of Swiss building practice. I did not know how to build. This was a serious issue. I didn’t know all the technical stuff, but still I felt there was something interesting going on. It took me a while to connect all the dots and this is how I discovered photography as a medium to enter the discourse on my own terms without having to build.

After all I’m on my own path trying to find a way to communicate and work with these experiences. Objectively there is so much more happening in space, or what we experience as such, than just architecture. Why are we talking only about architecture? Architecture is part of the conversation, but it is not the end of the conversation.

28.07.2022

艾丽卡-奥弗梅尔:住宅或者说居所是非常广泛的概念。我觉得,在做出选择之前,我需要正视几个问题,比如:什么是居住,我是如何生活的?社会是如何塑造我们今天的建筑的?探索这些问题的过程,使我以从前未尝试过的方式思考。我观察自己的住宅,我亲身参观过的住宅,以及我仅仅从书本或互联网上得知的住宅。

你的评判标准是什么?

我一直对定义城市空间的社会结构和它们所产生自然环境之间的关系感兴趣。我也思考过,随着时间的推移,火是如何从洞穴转移到居所,从住宅转移到城市的。

从一开始,壁炉就对人们的聚集、食物的准备和交换、舒适、庇护、玩耍以及从相聚中发展出来的社会习俗起到了作用。在工业革命之前,厨房——有火的房间,是大多数人在工作完成后花费大部分时间的空间。

在19世纪,当社会住房开始成为一种工业业务时,一种新的房屋组织类型形成了并得到巩固。它以某种方式浮现出,功能应该被划分为一系列独立的小房间,其中一个房间会有一个水龙头——被称为洗碗间。洗碗间反过来成为一个纯粹的功能性厨房,在这个时刻,"有火的房间 "不再是一个社交场所,一个多元的的、功能性的、灵活的中央房间。工业社会将个人的聚会从厨房中移除。它变成了一个禁锢的地方。它成了一个分离和隔离的地方,特别是对妇女而言。

它仍然构成了我们所知的大多数住宅和公寓的一个无可质疑的标准。我们倾向于认为我们不再生活在按等级组织的住宅中了。然而,这种模式仍然存在,至少在我看来,一种非常简单的、不受质疑的想法仍然主导着家庭空间的组织方式。

当你邀请我的时候,我开始寻找那些提出另一种可能性以替代那些受限于固定的、功能主义的陈词滥调的住宅,并承认存在一个更加流动的空间概念。

你是如何最终选择阿尔贝托-卡拉奇的拉普拉塔内拉(西语:香蕉)宅的?

起初,对于我们谈话的主题,我想选择丽娜客波客巴迪的维德罗住宅,主要也是为了将女性的立场带入谈话。多年来,该建筑的许多图像一直伴随着我,但我也从未亲自参观过这所住宅。在进一步检查了平面图后,我意识到它实际上是一个非常有等级感的住宅。它非常清晰,有一个仆人居住的地方,一个独立的厨房,其他隔离的空间,然后才是主要的展示空间,作为代表。虽然我真的很喜欢这个项目——而且我也喜欢丽娜客波客巴迪的大部分作品——但我感觉到,从社会和空间的角度来看,传统的等级制度在这所房子里仍然非常完整。在这种特定的情况下,你很容易被巴西的亚热带植被所吸引;悬浮在森林中的高架客厅的图像,令人惊叹的家具及其美妙的布置,大窗户和外面茂盛的植被。但实话说,这并不适合作为我想谈论的话题的案例。

在那之后,我专注于阿诺客布兰德胡伯的房子,我熟悉它的空间。在过去的十年里,我一直和他工作,我拍摄了他的大部分作品。我喜欢这些建筑的原因是,你无法说出住宅在哪里停止,其他东西从哪里开始,一个工作室或一个画廊似乎是公寓的一部分,它们无法言说地融在一起。

这些住宅,如果我们应该这样称呼它们的话,它们对不同的使用模式非常开放。在他为自己建造的建筑中尤其如此,人们使用空间的方式有一种非常有趣的流动性,这取决于一天中的不同时间,那里是温暖的,还是寒冷的,以及日常的、季节性的和个人的波动。例如,柏林的布鲁纳街是一座大住宅,在一楼和二楼有一个画廊。当我第一次访问时,阿诺的办公室在二楼,三楼和四楼是他的私人空间,或他在不同时期与不同的人、朋友、客人等共享的空间。

我记得其中有一种交流,在所有的程序和目的之间,这是我之前从未在某个城市住宅中见过的。你可以两个月后再来,一切都会在不同的地方。唯一不变的是炉子。甚至厨房也是一种过渡性的空间,没有明确的厨房特征。

尽管在他的建筑中,自然和文化之间没有模糊的边界,但我非常欣赏内部空间组织方式的模糊性。在我看来,这一点在今天的建筑论述中几乎没有涉及。每个人或多或少都同意我们需要什么样的内部组织。我反对这一点,相反,我相信在这个领域有很多东西要讨论,有很多事情要做,无论气候条件如何。

所有这些例子都清楚地表明了我感兴趣的话题,并且在你第一次给我写信的时候就已经搜索过了。

我在想禁锢、住宅功能和使用的分离、预定的组织、使用的自由、流动、循环、空间的自由以及内部和外部的关系、文化和自然、有序的和直觉的。

最后我意识到,我不断地回想起一个房子。这个历程把我带到了阿尔贝托-卡拉奇在墨西哥城的拉普拉塔内拉宅。

你去过那个住宅吗?

我第一次去的时候,我甚至不知道我要去哪里。人们只是拽着我走。我们在墨西哥城,在一个本来不显眼的普通住宅区,我们经过了许多无名的小街。在某一时刻,我只记得来到一堵平凡无奇的墙上的一扇门前,我们打开门,直接进入了一个花园,那是一个客厅。我真想要弄清楚我在哪里。前一秒我还在街上走着,过了门槛后突然看到一个毛皮吊床和一个软沙发,在一个用黑色火山石铺成的院子里,在大型热带植物之间。花园的某些部分有阴影,而且有一个屋顶。这是一个室外空间,同时也是一个室内空间。

一切都很大方,看起来非常豪华,但它在材料和细节上都非常简单。主人的父亲在厨房里,一个老人,正在泡茶。在隔壁的房间里,有人正坐着写东西。在另一个角落,有一些人在非常随意地闲聊。这感觉就像一个温馨的开放空间,人们、相关的朋友或家人可以随意进出;这感觉就像一个更大的社会网络的一部分。

我记得我喜欢墨西哥城人们的社会行为方式——公共空间如何成为私人空间,反之亦然。有一个非常有趣的社区互惠的想法,关于在一起,并一起使用空间。

这可能是受气候的影响,但这绝对是一种非常典型的社会组织形式。它在拉普拉塔内拉宅的空间中得到了明确的表达。这种空间配置留在我的脑海中,而没有过多考虑建筑师或它的建造时期。它只是一个非常酷和朴素的组织空间的方式。我觉得主要的空间是在自然和文化之间。它是非常民主的,关于它与周围环境的有机关系,它的使用和人们在那里的关系。

你对互联网上这座住宅的照片有什么看法?

它们是否正确地呈现了你所经历的感觉?

我认为网站上的图片没有传达出我在那里的感觉。据我观察,大多数摄影师似乎对更大的空间的群集不感兴趣,或无法识别,似乎大多数内容专注于一些细节或形式方面--希望这一切都会同时出现。我发现了一个很长的采访,采访的对象是业主和画廊主,他们谈到了这个空间的起源。它最初是一个修道院的一部分。拉普拉塔内拉宅的结构是在预先存在的历史墙壁上,我认为这给了它某种自由。它是层叠的。

卡拉奇的住宅随机地使用和接受了现有的建筑。它被松散地组织在一个院子周围,并由小单元组成,这些单元或多或少地沿着围墙连接,所有这些单元你一进门就能看到。其中一个被用作厨房,另一个被用作餐厅,另一个被用作阅览室,等等,所有这些都被打开并朝向庭院。唯一一个全新的空间是花园后面的空间——在那些香蕉树后面,这也是该项目名称的来源。这里是业主的更为私密的区域,我猜想他们在这里睡觉。所有这些意味着我们今天讨论的住宅毫无疑问是内向的,

它没有面孔,隐藏在一堵普通的、不引人注目的大墙后面。它的内部非常自由,但毫无疑问,它也是远离公众视野的。

最为打动人心的是进入时的惊喜感吗?

我认为这并不是什么惊喜的事。更让我印象深刻的是,阿尔贝托-卡拉奇和业主似乎都不关心表现性问题。从语境来看,它有一个完全反表现性的立面。可能有一些社会方面的原因,促使某些人去寻找隐蔽性。这也是当地建筑文化的特点,是私人和公共空间关系的一个方面。当时,我认为从心理学的角度来看,对于一个建筑师和业主来说,不做一个物体,不做一个表演,不做一个地位的象征,是非常有趣的。就我而言,它是这所住宅的一个非常鲜明的特征。它不是作为一个宣言,作为一个标志,它与所有这些东西完全相反。它完全融入了。

这所住宅所为何用呢?

几乎每一个我们所知道的建筑项目都涉及到表达的主题--它的外观和它打算对世界表达什么。拉普拉塔内拉宅完全跳过了这个话题。它纯粹是关于居住的——一个社交空间。这是一个建筑师真正的去做了一个美丽的、标志性的住宅,而没有任何大惊小怪的东西。

这是一个关于室内和室外空间的住宅,关于两者之间的模糊性。那里有不同类型的室外空间。有些房间里面也有植物。你有作为房间的花园,你也有作为花园的房间。美丽。你在那里,植物在你周围生长,你必须照顾它们,这也是你为什么这么爱它们的原因。有很多层面的关系在进行。所有这些丰富的东西都悄悄地发生在一个内部化的世界,其对城市没有形式上的表现。

是否有一个回归自然的废墟的想法?

还有一件事在我脑海中浮现,我认为这也是墨西哥的特点。也就是说,无序的概念,当它不再清楚某些东西是来了还是走了,是出现了还是减少了的状态。这种无序的模糊性对我来说是墨西哥空间现实的一个极其迷人的部分。

我今天早上还想到了巴拉甘和卡拉奇之间的比较。观察两人之间的代际转换很有意思,他们都在墨西哥城建造。巴拉甘来自一个非常富有的家庭,在农村长大,骑马,了解景观和植物等,后来在生活中为墨西哥城南部的火山地区制定总体规划,明确地与这个地区的自然和火山景观合作。

然而,在他后来的作品中,花园、自然的存在,几乎总是被简化为沉思的对象。有一种二元论的想法,即人类是自然的遥远而令人钦佩的观察者,而不是自然的一部分。有一种文化——内部空间的迷人序列,然后是自然——外部。这在他自己的住宅里特别明显,巴拉甘自宅。自然环境是非常重要的,但它们是需要被控制的东西。你有一个带巨大窗户的主房间,你可以看着大自然,但你不能出去。在主房间旁边有一个小房间,它有一个非常小的门通往花园。如果你需要,你可以进入花园,但花园必须维持为外部的事物。我不知道他为什么这样做。但这一切都让人感到非常不安,极度的控制和形式上的克制。

这种控制感和分离感是今天的设计哲学中仍然显著存在的东西,但它已经不可能持续,它不再起作用了。我们需要把事情作为一个整体来思考和看待。一切都是相连的。这种热带的直觉在卡拉奇的拉普拉塔内拉宅中尤其明显。

在墨西哥城,一般来说,长在花盆里的植物和长在花坛里的植物以及在街上野生的植被之间几乎没有什么区别。这一切都交织在一起。这可以适用于很多事情,但绝对不是指控制。然而,这些二元性似乎渗透到我们文化和社会的每一个方面。在卡拉奇的房子里,这种二元性通过了很多方式得到了解决。在许多方面,它是一个非常民主的空间。

新旧之间的关系重要吗?

有时是的,有时并不重要。这一切都取决于语境。然而,建筑师和项目开发商似乎依然主要对一种被规划过的白板状态感兴趣。实际上,我对乡土建筑或非预设性的建筑更感兴趣,一种使用上自然分层的复杂性和模糊性。我觉得这需要一种更高层次的智慧,这绝对不是建立空间层次的问题。一个非常重要的层面是,你无法阐明之前的东西和之后的东西之间的区别,因为所有的东西都是一个过程,没有什么是真正新的。它更像是先有的东西,我们对它的反应,以及接下来的层次是什么,社会上的,空间上的,以及这一切是如何联系起来的。然而,有时一些新鲜的东西正是我们所需要的。拉普拉塔内拉宅不像是一种智识上的论述或练习,它只是非常的实用和有机。

我从图片中得到的印象是,材料和细节的选择思路是相当清晰的,很容易看到什么是新的,什么是既有的。我说得对么?

我认为这部分是由于存在的那种图片。当你去那里时,你不确定。而且这并不重要。细节不是你注意到的第一件事。好吧,至少对我来说,完全让我倾倒的第一件事是室内与室外,在内与在外的划分所造成的模糊性。

一切都渗透着被当地海拔压低的柔和的声音,鸟鸣,来自街道的遥远的声音,车辆经过,树叶的沙沙声和轻轻移动的阴影,阳光的色调和品质,一阵清风——所有这些都塑造了空间体验。这些都是摄影只能暗示的感觉。

作为一个与建筑打交道的摄影师,你对你的领域有什么看法?

说得极端一点,它不像一片田野(与领域语义双关),而更像一片沙漠。在我看来,大多数摄影师似乎都聚焦在事物或物体上,专注于美学或形式方面,项目被有意地孤立于它的语境和周围环境。在一个崇尚易读性的背景下,以营销为目的和方便消费而制作的图像。但事情不应该是这样的。

我认为摄影有能力容纳矛盾、复杂、模糊、多样性和不确定性——作为一种对话和论述的形式。或者至少这是我感兴趣的地方。我想对我正在看的东西含糊其辞——或者直接与矛盾和含糊的情况一起工作。这最终,在某些方面,与建筑有关,但它不是关于建筑的。

你是如何得出这种认知的?

我一直知道,甚至在我能用语言表达之前,我对空间的一致性和我们如何体验空间感兴趣,不管那是什么,或者它是如何表现的——在我们存在于世界的最大意义上。

我开始于一个艺术学校的工作室,对空间处理方法的另类叙述相当感兴趣和关注。我们看了很多AA当时正在做的事情,它是非常实验性的。

没有规程,同时也确实有一个规程。它必须发挥作用。你需要 "设计",并有标准使其发挥作用。我总是觉得,在空间中还有其他的东西,不仅仅是关于功能。对我来说,它是关于社会、空间甚至情感的体验。我想要找出我们可以如何谈论这个问题。

作为荷兰皇家艺术学院(Gerrit Rietveld Academie)的学生,我邀请雅克-赫尔佐格参加一个公开会议。雅克来了,并说了些话。我想,好吧,也许有一个办法。他说了非常有趣的事情。当时我不知道该往哪儿看。雅克也是一种邀请,他说 "当你毕业时,到我们这里来"。而这基本上就是我所做的。我想我是第一个在赫尔佐格与德梅隆事务所那里工作的外国人。但我的背景和兴趣让我对瑞士建筑实践的现实和严格性准备不足。我不知道如何建造。这是一个严重的问题。我不了解所有的技术内容,但我仍然觉得有一些有趣的事情在发生。我花了一些时间来连接所有的点,这就是我如何发现摄影作为一种媒介,以我自己的方式参与进讨论,而不需要建造。

毕竟我在自己的道路上,试图找到一种方法来沟通和处理这些经验。客观地说,在空间中发生的事情太多了,或者说我们所经历的事情,不仅仅是建筑。为什么我们只谈论建筑? 建筑是对话的一部分,但它不是对话的终点。

2022年7月28日

エリカ・オーフェルメール: 家や住まいというものは、意味の広い概念ですよね。ですから、住宅として何を選ぶかよりも、まずは自分自身に問いを投げかける必要がありました。住むとはどういうことなのだろうか?私はどうやって生きるのだろうか?どのようにして社会が建築を形づくるのだろうか?こういった問いへの探求が、私に考えさせる時間をくれました。自分の家や、かつて訪れたことのある家、本やインターネットで見たことのある家などを見てみることにしました。

何を評価基準とされたのですか?

私は、都市空間を形成する社会構造と、そこで生じる自然環境との関係に常に興味を持っていました。また、時代と共に、洞窟の中の火が住居の中へと移動し、そして、住居の中から都市の中へと移動していったことを考えたのです。

もともと暖炉というものは、人の集まる装置でした。食料を交換し、蓄える場所として。心地良い避難所として。それに遊び場として。社会的慣習もそうやって人が集まることで発展したものです。産業革命以前のキッチンとは、火のある部屋のことであり、みんな仕事終わりにはそこでほとんどの時間を過ごしたのです。

19世紀は、ソーシャルハウジングが産業のビジネスへと変化し始めた時期です。その新しいタイポロジーは、家がどうあるべきかを明確に固定してしまうようなものでした。どういうわけか、機能は独立した小さな部屋に分割され、そのうちの一つに蛇口がつけられました。そこがスカラリーと呼ばれたのです。そうして、スカラリーは純粋に機能的なキッチンとなりました。その瞬間に「火のある部屋」は、社交のための場ではなくなりました。かつては、フレキシブルな家の中心として、複合的で機能的な部屋だったのですよ。

産業社会によって、キッチンに人が集まることはなくなりました。キッチンは監禁の場所、つまり分離と隔離の空間となりました。特に女性にとってはね。

そのことは、私たちのよく知る多くの戸建てや集合住宅において、今でも揺るぎない基準となっています。私たちの住まいが、ヒエラルキーで組織化された家であるとは、誰も思いません。ですが、実際は依然としてそういったものが残っているのです。とても単純で疑問の余地もないような考えが、実は、家庭空間のあり方を支配している。少なくとも私にはそう思えるのです。

このインタビューへの誘いを受けて、凝り固まった紋切り型の機能主義に対するオルタナティブとして、流動的な空間のコンセプトをもった住まいを探し始めました。

アルベルト・カラチのラ・プラタネラを選ばれたのはなぜですか?

最初は、会話のトピックとしてリナ・ボ・バルディのバルディ邸を選ぼうと思っていました。特に女性の話を持ち込むにはいいだろうと。その建物のイメージが、私の頭の中には何年もの間残っていたのです。ついに訪れることはなかったのですが。ところが、平面図をよく見てみると、実はかなりヒエラルキーの組織化された住宅だと気づきました。とても明解に作られています。召使いの住む場所があり、独立したキッチンがあり、その他にも分割された空間があり、そしてディスプレイとしてのメインスペースがある。つまり表現としての空間です。とても好きなプロジェクトですよ。リナ・ボ・バルディの作品はどれも大好きですし。ですが、社会的、あるいは空間的な視点から見るとこの住宅には、伝統的なヒエラルキーがそのまま強く残っているんです。こんな特別なシチュエーションの中では、ブラジルの亜熱帯植物にすぐに目がいってしまいますよね。森の中に吊り下げられたリビングルーム。素晴らしい家具たちの美しいまとまり。大きな窓に青々とした外の緑。ただ、これらは私の話したかった内容とは関係のないことです。

その後、私のよく知るアルノ・ブランドフーバーの住宅と、その空間に着目してみました。彼とは10年以上の付き合いですし、彼のほとんどの作品を写真に撮ってきました。それらの建物は、どこから始まってどこで終わっているかが、よくわからない感じで好きなんです。スタジオやギャラリーも住居の一部のようになっていて、不可解な形で溶け合っています。

これらは、言ってみれば、多様な用途に開かれた住居ということなのでしょうか。彼の自邸において特に顕著なことですが、時間帯の変化や、場所による寒暖の変化、日常あるいは季節的な変化、そして個人の気持ちの変化など、いろいろ変化によって空間の使い方が変わっているのです。この流動性はとても面白いですね。例えば、ベルリンのブルネン通りにある大きな住宅は、地上階と2階にギャラリーがあるのですが、私が訪れた時、アルノの事務所は3階にあって、4階と5階は彼のプライベートスペースとして、彼の友人やゲストなどの様々な人と過ごすことのできる空間になっていました。

あらゆる機能と目的とが入れ替え可能になっています。そういった形の都市の住宅は見たことがありませんでした。二ヶ月後には、あらゆるものが違う場所に配置されていることもあり得ます。同じ場所にあり続けるのは、ストーブだけ。キッチンでさえキッチンらしい設えがなく、移動可能な空間になっています。

彼の建築には、自然と文化との境目がなく、その内部空間の作る曖昧さは素晴らしいと思います。今日の建築的議論の中では、あまり取り上げられていないようなことだとは思いますが。内部空間がどうあるべきかについて、みんなそんなに疑問を持つことはないのでしょう。ですが、私は逆にもっと議論すべきなのだと思いますし、いろんな取り組みがなされるべきだと思います。それは風土とは、関係のないことだと思います。

あなた方からのインタビュー依頼を受けて、私は、こういったことに興味を持ち、探求していたのだという事が改めて明確になってきました。

住宅内での監禁的状態、機能や用途の分離、決まりきった組織化の方法。そういったことに対する、用途の自由さ、空間の流動性や回遊性、そして自由度。内部と外部、文化と自然、秩序と直感との関係性。これらは、私が考えてきたことです。

そして、結局いつも同じ住宅のことを考えていたのだと気づきました。メキシコシティにあるアルベルト・カラチのラ・プラタネラです。

そこには、行かれたことがあるのですか?

そこへ初めて行った時は、自分がどこへ向かっているのかもわからないような状態でした。ただ、連れられて。メキシコシティの、とりわけ特徴のない普通の住宅街にある小さな脇道を抜けて行きました。あるところで、ドアの前に到着したことを覚えています。のっぺりとした、なんてことはない壁面につけられたドア。そこを開けると、すぐに庭の中に入っていることに気づきました。しかも、そこがリビングでもあったのです。私はどこにいるのだろうか、と考えざるを得ませんでした。歩き出すとすぐに、ある領域に入ったのがわかりました。突然、大きな熱帯植物の間から毛皮のハンモックや柔らかなソファが見えてきました。それらは、黒の火山石の敷き詰められた中庭に置かれていました。庭の中は、所々に影が作られ、屋根のかかっているところもありました。そこは外部空間でもあり同時に内部空間でもあるような場所でした。

あらゆるものが寛大で、そしてラグジュアリーに見えました。ところが、素材やディテールはすごくシンプルなのです。キッチンにはオーナーのお父さんがいました。とても高齢の方でしたが、そこでお茶を入れていました。その横の部屋では誰かが座って書き物をしていて、また別のコーナーではガヤガヤと雑談している人たちがいました。とてもウェルカムで開けた家でした。友達や親族、あるいは家族が勝手にやってきて、また出ていくというような、大きなソーシャルネットワークの一部のような場所だと感じられました。

メキシコシティでの人々の社会的な振る舞い方が、とても好きだったことを思い出します。パブリックスペースとプライベートスペースが入れ替わるような振る舞い方です。人と一緒に空間を共有する際のコミュニティが持つ相互扶助的な考え方が、とても興味深いのです。

気候がそうさせるのかもしれませんが、それが典型的なこの社会の組織化の方法であることは間違いありません。そういった点から考えると、ラ・プラタネラの空間は理解しやすいでしょう。誰が作ったとか、どの時代だとかは関係なく、この空間構成は、私にとってはとても印象深いものでした。ただクールで、気取りのない空間構成。メインスペースは、自然と文化との中間にあるような空間に感じられましたし、周辺環境や空間の使われ方、そしてそこにいる人々との有機的な関係性は、とても民主的なものでした。

インターネットで見られるこの住宅の写真についてはどう思われますか?そこに、経験されたようなことは表現されているのでしょうか?

ウェブサイトにある写真では、私がそこで感じたようなことは伝えられていないと思います。私が見てきた多くの写真家は、空間の構成を俯瞰して捉えることができないのだと思います。あるいは、興味がないのでしょう。ですから、大抵はディテールや形式的な側面に焦点が当てられています。本当は、それらが統合されるべきなのだと思いますが。この家のオーナーであり、ギャラリストである方へのロングインタビューの記事を見つけました。そこで、この家の起源が語られていました。もともとは修道院だったそうです。ラ・プラタネラは、その既存の歴史的な壁の上に新しく作られたのだと。この自由な感じはそこから生まれているのだと思います。歴史のレイヤーが積み重なっている、ということですね。

この住宅は、既存の建築を適度に受け入ながら利用しています。周囲の壁面に沿って、小さなユニットが緩やかに中庭を囲っていますね。中に入ると、そのことがすぐにわかると思います。一つはキッチンとして使われていて、その他はダイニングルームや、読書室などに使われています。全てが中庭に向かって開いています。庭の奥には、ここで唯一の全く新しく作られた空間があるのです。それはプラタナスの木に隠されています。プラタナスの木は、このプロジェクトの名前の由来となっていますね。ここがオーナーのプライベート空間になっていて、ここで寝たりするのでしょう。つまり、今議論しているこの住宅は、実は紛れもなく、内向的な性質をもっているということです。

顔がなく、のっぺりとした巨大な壁の後ろにあるのは、内部の自由さと、公共の目からは全く閉ざされた世界、というわけです。

入った時に感じる驚きが、最も印象に残っていることでしょうか?

驚きということよりは、アルベルト・カラチもクライアントも表現ということに対してあまり興味がなさそうな事が、とても印象的でした。このファサードなんて都市の中でも全く無表情なものです。何かの社会的側面が、こういった特定の人々をインビジブルなものへと向かせるのでしょうか。あるいは、それがここでの建物の文化、つまりプライベートな空間とパブリックな空間との関係性における特徴なのかもしれません。建築家やオーナーは、ステータスの象徴としてのオブジェを作ったり、それをひけらかすようなことを控えている。その心理的な側面にも興味を持ちました。この住宅はそういったこととは真逆で、ステートメントやアイコンとして作られているわけではない。そのことが逆に強烈な個性となっています。周囲に完全に溶け込んでいますね。

この住宅はなんのためにあるのでしょうか?

私たちの知っているような、ほとんど全ての建築プロジェクトは、表現の問題と関わっています。つまり、世界に対して何を表現するのか、ということです。ラ・プラタネラはこういった表現の問題を完全にスキップしていて、つまり純粋に、住まいであるということです。そして社会的空間である。建築家は、無駄なことなど言わず、本当に美しい住宅を作ったのです。

内部と外部、そしてその二つの曖昧さ。さまざまなタイプの外部空間。植物の置かれた内部空間。部屋としての庭。庭としての部屋。美しいでしょう。植物は育ってきますから、手入れをしなくてはいけません。だからこそ愛おしく思える。植物との関係性はさまざまですが、これら全ての豊かさは、内面化された世界においてひっそりと育まれるものです。都市には背を向けたまま。

自然によって廃墟化することで、生き生きとしてくるといったことも考えられますか?

そういったことも考えていました。とてもメキシコ的な特徴だと思います。つまり、ここではエントロピーの考え方が特徴的で、来ているのか去っているのか、増えているのか減っていっているのか、そういったことがもはやわからなくなる。このエントロピーの不明瞭さが、とても面白い。それがメキシコ的空間のリアリティなのだと思います。

今朝もバラガンとカラチの違いを考えていました。この二人の世代的な違いを見てみるのも面白いと思います。二人ともメキシコシティで作っていますよね。バラガンは裕福な家庭で生まれ、田舎で育ちました。馬にも乗っていたのでしょう。ランドスケープや植物などのこともよく知っていました。後にメキシコシティの南部にある火山地帯のマスタープランを計画していましたね。火山と自然のランドスケープとの関係がよく考えられたものでした。

ところが、彼の後期の作品では、庭、つまり自然の存在が小さくなっていきます。自然は、ほとんど瞑想のための対象物となってしまいました。人間は自然の一部ではなく、それを観察し賞賛する遠く離れた存在である、という二元論的な考えが見て取れます。文化的なのです。魅力的な内部空間のシークエンスがあり、自然がある。でもそれは、外部としての自然だということです。彼の自邸、バラガン邸ではそのことが顕著に見て取れます。自然環境はとても重要な役割を果たしてはいますが、自制すべきものとして扱われているのです。巨大な窓のあるメインルームからは、自然を見ることはできますが、外へ出ることはできません。庭へ出るには、メインルームの脇にある小さな部屋の、さらに小さなドアから出ていくのです。必要となれば、庭へは出ることができる。ところが、基本的には、庭は外にあるべきだということです。彼がなぜそうしたのかわかりません。とても窮屈に感じますし、極度にコントロールされていて、堅苦しく拘束的な感じがします。

こうした支配と分離といった感覚は、現在の哲学においても未だ根強い感覚だと思います。しかし、それを維持することはもはや不可能で、機能するものではないと思います。私たちは、物事を全体として見るべきなのだと思います。全ては繋がっているのだと。こういった熱帯的直感が、カラチのラ・プラタネラには表れていますね。

メキシコシティでは、鉢や花壇から育つ植物と、道から自生する植物との間には、ほとんど違いが見られません。全てが絡み合っている。これは、いろいろなことへ応用できる考え方だと思います。支配的な考えとは全く異なるものですよね。今でも二元論的な考え方は、私たちの文化や社会のあらゆるところに浸透していますが、このカラチの住宅では、その二元論的な考え方がさまざまな方法で解決されてるのです。民主的ですよ。いろいろな意味でね。

新旧の関係が重要だということでしょうか?

そうだとも言えますが、関係ないときもありますね。コンテクストによるでしょう。建築家やプロジェクトの開発者の多くは、わかりやすく計画されたタブラ・ラーサに興味を持つようですが。私は、土着的な、あるいは控えめな建築の方に興味がありますね。自然な形で階層化された複雑さを持っていて、用途に多義性をもった建築です。それには、高い次元での知性が必要だと思います。それは、空間的なヒエラルキーを作るということではないですよ。以前からあったものと新しくできたもの、その違いが明瞭に示せないことこそが重要なのだと思います。全てが過程であって、新しいものは何もないのだと。何かから始まって、それに答えて、その次がまたやって来て、というような形で、社会的にも空間的に全てが繋がっているのです。時には、フレッシュで本当に新しいものが必要とされる時もあると思いますが。ラ・プラタネラは知的なディスコースでもエクササイズでもありませんね。実利的で有機的なものです。

私が写真を見た印象からは、素材やディテールの選択が極めて明快で、新旧の区別もすぐにわかったくらいです。私が変なのでしょうか?

おそらく写真のせいだとは思いますが、行ってみてください。新旧の区別は難しいと思います。でもそんなことはどうでも良いでしょう。最初に目につくのは、ディテールではないと思います。そうですね。少なくとも私にとっては、内部と外部の表現によって生まれる曖昧な領域には、目眩を覚えました。

標高の高さから生じる鈍く柔らかな音、鳥のさえずり、通りから聞こえる遠くの声、通り過ぎる車、さらさらと優しく揺れ動く葉の影、太陽光の素晴らしさ、そのトーン、小さなそよ風、それら全てが浸透しあって、空間の経験を形成しています。こういったことは、写真だけが仄めかすことのできる感覚です。

建築に携わる写真家として、ご自身の専門分野に対しては、どのようなことをお考えですか?

極端に言えば、分野といっても砂漠みたいなものですよ。ほとんどの写真家は、事や物に集中して、美的で形式的な側面に多くの焦点を当てています。そして、プロジェクトはそのコンテクストや周囲の環境から意図的に隔離されてしまっています。広告目的で作られ、わかりやすさが賞賛される環境の中で、容易に消費されてしまうイメージたち。そういった写真のことではないのです。

写真には、矛盾や複雑さ、曖昧さや多様性、そして不確かさを維持する力があると考えています。それは、ダイアローグとディスコースの形式ということでしょうか。少なくとも、私の興味はそこにあります。私は、私の見ているものに対して曖昧でありたいと思っていますし、相反的で両義的なシチュエーションに対して真っ向から取り組みたいと思っています。そういったことを思っていると、どうしても建築が関係してきます。それこそが建築であるということではないですが。

どのようにして、こういった認識に到達されたのですか?

言葉にする前から、わかっていたのだと思います。私は、空間の一貫性や空間の体験といったものに興味を持っていました。それがどんなものであるのか、何が表現されているのか、は関係ありません。私たちが世界の中にいる、というとても広い意味での興味です。

私が美大のスタジオ課題に取り組み始めたときのことです。スタジオでは空間的なアプローチに対する、代替としてのナラティブに関心が向けられていました。当時は、AAスクールがしていたことをよく見ていました。とても実験的なものでした。

課題としての実施要綱はないはずです。でも実際にはあるも同然だったのです。機能しなくてはいけないですから。「設計」しなくてはいけなかったですし、それが機能するための基準もありました。私は、機能だけではない何かが、空間にはあるのだと感じていました。私にとってそれは、社会であり、空間的で感情的な経験のことでした。どうすれば、そのことを議論できるのか考えていました。

私は、リートフェルトアカデミーの学生として、ジャック・ヘルツォークをパブリックカンファレンスに招待しました。彼は来てくれて、話をしてくれました。道が開けた感じがしました。彼の言っていたことがとても面白かったのです。当時、私は、どこへ向かえばいいのかわかっていませんでした。そんな時に「卒業したら、うちに来てよ」とジャックが誘ってくれたのです。私のしてきたことは、基本的にはそれだけです。私が、ヘルツォーク&ド・ムーロンで働いた初めての外国人だったと思います。ところが、私のそれまでの経験や興味だけでは、スイスの建築実務の厳しさや現実を受け入れる準備ができていませんでした。建てる方法がわからなかったのです。深刻な問題でした。技術的なことは何一つわからなかったのですが、何か面白いことが起きているということだけは感じられました。全ての点を結びつけるには、しばらく時間がかかりましたが、こうして、建物を建てずとも、自分の言葉で議論に参加できるメディアとして写真を発見できたのです。

こういった経験を通して、コミュニケーションや仕事をする方法を模索しつつも、私は私の道を切り開いていきました。考えてみれば、建築の中に限らず、空間の中や、私たちのこうした経験の中では、もっともっといろんな事が起きています。なのに、なぜ私たちは建築のことだけを話しているのでしょう?建築は会話の一部であり、それが全てではないでしょう。

2022年7月28日

Erica Overmeer: A house or a dwelling are very broad notions. I felt, that before making a choice, I needed to confront myself with questions like: What is it to dwell, how do I live? How does society shape what we are building today? The time spent exploring these questions, got me thinking in ways that I had not tried before. I looked at my own house, the houses I had visited, the houses I knew only from books or the Internet.

WHAT WERE YOUR CRITERIA?

I have always been interested in the relationship between the social structures that define urban spaces and the natural settings where they appear. I also thought about how over time the fire moved from a cave to a dwelling, from a house to a city.

Since the beginning a fireplace has been instrumental in gathering people, in the exchange and preparation of food, comfort, shelter, play, and the social customs that developed out of being together. Before the industrial revolution the kitchen - the room with the fire, was the space where the majority of people spent most of their time after the work was done.

In the 19th century, in the moment when social housing started to be an industrial business, a new typology crystallised and consolidated on how a house should be organised. It somehow emerged that functions should be divided between a series of small separate rooms and one of them would have a water tap - and be called a scullery. The scullery in turn became a purely functional kitchen and in this very moment „the room with the fire” stopped being a social place, a plural, functional, flexible central room. Industrial society removed the meeting of individuals from the kitchen. It became a place of confinement. It became a place of separation and segregation, especially for women.

It still constitutes an unchallenged standard for the majority of houses and apartments we know. We tend to think we no longer live in hierarchically organised houses. However, this model still persists and, it seems to me at least, that a very simple minded, unquestioned idea still dominates how domestic spaces are organised.

When you invited me, I started to look for dwellings that proposed an alternative to a fixed, functionalist cliché and acknowledged a more fluid concept of space.

HOW DID YOU END UP CHOOSING THE ALBERTO KALACH’S LA PLATANERA HOUSE?

At first, for the topic of our conversation I wanted to choose Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro, notably also to bring a female position to the conversation. Over the years, many images of the building had stayed with me, but I had also never visited the house in person. After further examination of the floor plans I realised that it is actually a very hierarchically organised house. It is very clear, there’s a place where the servants live, a separate kitchen, other segregated spaces and then the main space of display, of representation. Although I really love this project – and I love the work of Lina Bo Bardi in general – I had the feeling that from a social and spatial point of view, traditional hierarchies where still very much intact in this house. You can easily be distracted by the sub tropical vegetation of Brazil notably in this specific situation; the images of the elevated living room suspended in the forest, the beautiful configuration of the amazing furniture, the big windows with the lush vegetation outside. In truth, this was not going to work as an example for what I wanted to talk about.

After that, I concentrated on the houses of Arno Brandlhuber, spaces that I know well. I’ve been working with him for the last ten years and I have photographed most of his work. What I like about these buildings is that you cannot say where the house stops and something else starts, a studio or a gallery seems to be a part of an apartment, they melt together inexplicably.

These are houses, if this is how we should call them, that are very open to diverse modes of use. It is especially true in the buildings he built for himself, there’s a very interesting fluidity in the way one uses the space depending on the time of day, where it’s warm, or cold, and following daily, seasonal and personal fluctuations. Brunnenstrasse in Berlin, for instance is a large house with a gallery on the ground and first floor. When I first visited, Arno’s office was on the second floor, and on the third and fourth floor there were his private spaces or spaces he shared at different times with different people, friends, guests, etc.

I remember a kind of exchange between all the programs and purposes, that I had never seen before in a city house. You could come two months later, and everything would be in a different place. The only thing that remained constant was the stove. Even the kitchen was a kind of a transitional space without a clear kitchen-like character.

Even though in his architecture there are no blurred borders between nature and culture, I very much appreciate the ambiguity in the way the interior spaces are organised. It seems to me something that it is hardly addressed in architectural discourse today. Everybody more or less agrees on what kind of internal organisation we need. I counter this and believe instead, that there is a lot to be discussed and a lot to be done in this field, regardless of climatic conditions.

All these examples made clear the topics I am interested in and had searched for when you first wrote to me.

I was thinking about confinement, separation of functions and use in a house, predefined organisation, freedom of use, fluidity, circulation, freedom in a space and the relation between inside and outside, culture and nature, ordered and intuitive.

In the end I realised that I was constantly coming back to one house. This journey brought me to La Platanera by Alberto Kalach in Mexico City.

HAVE YOU BEEN TO THE HOUSE?

The first time I went there, I didn’t even know where I was going. People just tugged me along. We were in Mexico City, we passed through many anonymous, small side streets in an otherwise unremarkable and ordinary residential area. At some point I just remember coming to a door in a plain unassuming wall, which we opened, and entered directly into a garden, which was a living room. I really had to make sense of where I was. A second before I walked down the street, and suddenly after passing the threshold I saw a fur hammock and a soft sofa in a courtyard paved with black volcanic stone between large tropical plants. Some parts of the garden where shaded and had a roof. It was an outdoor space that was an interior space at the same time.

Everything was generous and looked very luxurious, but it was very simple in both material and detail. There was the father of the owner in the kitchen, an elderly man, making a tea. In the next room someone was sitting and writing. In another corner, there were some people chit-chatting very informally. It felt like a welcoming open house where people, related friends, or family, could just come and go; it felt like part of a larger social network.

I remember I liked the way people behaved socially in Mexico City - how public spaces become private spaces and vice versa. There’s a very interesting reciprocal idea of community, about being together, and using the space together.

It might be motivated or informed by the climate – but it definitely is a very typical form of social organisation. It finds its explicit expression in how the spaces of La Platanera are made. This spatial configuration stayed in my mind without thinking much about the architect or the period when it was built. It was just a really cool and unpretentious way to organise space. I felt the main space was somewhere between nature and culture. It was very democratic, in regard to the organic relation to its surroundings, to its use and to people being there.

WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE PICTURES OF THE HOUSE AVAILABLE ON THE INTERNET? DO THEY RENDER CORRECTLY THE FEELING YOU EXPERIENCED?

I think that the pictures on the website are not conveying the feeling I had when I was there. From what I observe most photographers seem not to be interested in, or unable to recognise larger spatial constellations, and seem mostly content focussing on some details or formal aspects – hoping it will all come together. I found a long interview, with the owners, gallerists, who spoke about the origins of this space. It had originally been part of a convent. La Platanera is structured on preexisting historic walls, which I think gives it a certain freedom. It’s layered.

Kalach’s house randomly uses and accepts the existing architecture. It’s loosely organised around a courtyard and by small units that are more or less connected following the perimeter wall, all of which you see immediately upon entering. One of them is used as a kitchen, another as a dining room, another as a reading room, etc. all opened and oriented towards the courtyard. The only entirely new space is the one at the back of the garden – behind the Platana trees that also give the project its name. This is where the owners have their more private areas, where they sleep I assume. All this means the house that we discuss today is without question introverted, its faceless and hidden behind a plain and unremarkable large wall. It’s very free inside, but it is also, without doubt, closes away from public view.

WAS THE SURPRISE EFFECT THE MOST STRIKING SENSATION UPON ENTERING?

I think it’s not so much about the surprise. What struck me more was the fact that neither Alberto Kalach nor the clients seemed to care about representation. In context, it has a completely unrepresentative facade. There might be some social aspects that push certain people to look for invisibility. It is also characteristic for the local building culture, an aspect of the relation of private and public spaces. At the time, I thought it was very interesting from a psychological point of view, for an architect and an owner, to refrain from making an object, a show, a symbol of status. As far as I am concerned, it is a very powerful feature of this house. It is not made as a statement, as an icon, it is the complete opposite of all these things. It blends in completely.

WHAT IS THIS HOUSE FOR?

Almost every single architecture project that we know about is concerned with the topic of representation - how it looks and what it represents to the world. La Platanera completely skips this topic. It is purely about dwelling - a social space. This is an architect who really makes a beautiful, iconic house without making any fuss about it.

It’s a house about indoor and outdoor space and about the ambiguity between both. There are different types of outdoor spaces. Some rooms also have plants inside. You have gardens that are rooms and you have rooms that are gardens. Beautiful. You are there, the plants grow around you, you must take care of them, and it’s also why you love them so much. There are relations going on on many levels. All this richness happens quietly in an internalised world that has no formal representation towards the city.

IS THERE AN IDEA OF A RUIN BEING RECLAIMED BY NATURE?

There’s another thing that comes to my mind, which I also think is very characteristic of Mexico. Namely, the idea of entropy, the state when it’s no longer clear whether something is coming or leaving, emerging or diminishing. This entropic ambiguity is for me an extremely fascinating part of Mexican spatial reality.

I thought this morning also about a comparison between Barragàn and Kalach. It’s interesting to observe the generational shift between the two, both of whom built in Mexico City. Barragàn came from a very rich family, growing up in the countryside, riding horses, knowing about landscape, plants etc. and later in life developing masterplans for the volcanic South of Mexico City, explicitly working with the natural and volcanic landscape of this area.

However in his later work, the gardens, the presence of nature, are reduced, almost always, to objects of contemplation. There is a dualistic idea of humans being distant and admiring observers of nature, rather than being part of it. There is a culture - an alluring sequence of interior spaces, and then nature - an exterior. It is especially evident in his own house, Casa Barragàn. The natural surroundings are very important, but they are something to be contained. You have the main room with a huge window, you can look at the nature, but you cannot go out. There is a small room next to the main room and it has a really small door to the garden. You can enter the garden if you need to, but the garden must remain something that’s out there. I don’t know why he did this. But it all felt very uneasy, extremely controlled and formally restrained.

This sense of control and separation is something still very present in the philosophy of today, but it’s no longer possible to sustain, it doesn’t work any longer. We need to think and look at things as an entirety. Everything is connected. This tropical intuition is very present in La Platanera of Kalach. In Mexico City, there is generally very little difference between a plant that grows in the pot and a plant that grows in a flower bed and the vegetation that grows wild in the street. It’s all intertwined. This could apply to many things but it is definitely not about control. Yet, these dualities seem to permeate every aspect of our culture and society. In Kalach’s house, this duality is resolved in many ways. It is a very democratic space, in many ways.

IS THE RELATION BETWEEN OLD AND NEW IMPORTANT?

Sometimes yes, sometimes it doesn’t matter. It all depends on the context. Yet architects and project developers seem still mostly interested in a perceived or planned tabula rasa. I am actually more interested in vernacular architecture, or non-assuming architecture, a naturally layered complexity and ambiguity of use. I feel it requires an intelligence of a higher order, which is definitely not about establishing spatial hierarchies. A very important aspect is that you cannot articulate the difference between what was there before and what came after, because everything is a process and nothing is really new. It’s more like what comes first, how we react to it, and what the next layers are, socially, spatially, and how all this is all connected. And yet, sometimes something fresh and new is exactly what is needed. La Platanera doesn’t feel like an intellectual discourse or exercise, it’s just very practical and organic.

The impression I get from looking at the pictures, is that the choice of the materials and detailing is quite clear, it’s easy to see what is new and what was there before. Am I wrong?

I think this is partly due to the kind of pictures that exist. When you go there, you’re not sure. And it doesn’t matter. The details are not the first thing you notice. Well, at least for me, the first thing that completely put me out of balance was the ambiguity created by the delineation of interior and exterior, inside and outside.

Everything is permeated by the soft sounds muffled by the altitude, birds, distant voices from the street, vehicles passing, the rustling and softly moving shadows of the leaves, the tone and quality of sunlight, a small breeze – all inform the spatial experience. These are sensations that photography can only hint at.

AS A PHOTOGRAPHER WORKING WITH ARCHITECTURE, WHAT IS YOUR POINT OF VIEW ON YOUR FIELD?

To put it in the extreme, it doesn’t feel like a field but more like a desert. It seems to me that most photographers seem to concentrate on things or objects, intently focusing on aesthetic or formal aspects, with the project purposely isolated from its context and surroundings. Images produced for marketing purposes and easy consumption in a context that prizes easy legibility. But that’s not what this is about.

I think that photography has the capacity to hold contradiction, complexity, ambiguity, diversity, and uncertainty – as a form of dialogue and discourse. Or at least that is what I’m interested in. I want to be ambiguous about what I’m looking at — or work directly with ambivalent and ambiguous situations. This eventually, at some point, has to do with architecture but it is not about architecture.

HOW DID YOU ARRIVE TO THIS AWARENESS?

I always knew, even before I could put it in words, that I was interested in spatial coherence and how we experience space, whatever that is or however it is manifested – in the largest sense of our being in the world.

I started out in an art school studio that was quite interested and concerned with alternative narratives of spatial approaches. We were looking a lot at what the AA was doing at the time, it was very experimental. There was no protocol and at the same time there was indeed a protocol. It had to function. You needed to ‘design’, and there were criteria to make it work. I always felt, there was also something else in space that was not only about function. For me it was about a social, spatial and even emotional experience. I wanted to find out how we could talk about that.

As a student at the Rietveld Academy I invited Jacques Herzog to a public conference. Jacques came, and he talked. I thought, well, maybe there is a way. He was saying very interesting things. At the time I didn’t know where to look. Jacques was also kind of inviting, saying: „come to us, when you graduate”. And that is basically what I did. I think I was the first foreign person working in Herzog&de Meuron ever. But my background and interests hardly prepared me for the reality and rigour of Swiss building practice. I did not know how to build. This was a serious issue. I didn’t know all the technical stuff, but still I felt there was something interesting going on. It took me a while to connect all the dots and this is how I discovered photography as a medium to enter the discourse on my own terms without having to build.

After all I’m on my own path trying to find a way to communicate and work with these experiences. Objectively there is so much more happening in space, or what we experience as such, than just architecture. Why are we talking only about architecture? Architecture is part of the conversation, but it is not the end of the conversation.

28.07.2022

艾丽卡-奥弗梅尔:住宅或者说居所是非常广泛的概念。我觉得,在做出选择之前,我需要正视几个问题,比如:什么是居住,我是如何生活的?社会是如何塑造我们今天的建筑的?探索这些问题的过程,使我以从前未尝试过的方式思考。我观察自己的住宅,我亲身参观过的住宅,以及我仅仅从书本或互联网上得知的住宅。

你的评判标准是什么?

我一直对定义城市空间的社会结构和它们所产生自然环境之间的关系感兴趣。我也思考过,随着时间的推移,火是如何从洞穴转移到居所,从住宅转移到城市的。

从一开始,壁炉就对人们的聚集、食物的准备和交换、舒适、庇护、玩耍以及从相聚中发展出来的社会习俗起到了作用。在工业革命之前,厨房——有火的房间,是大多数人在工作完成后花费大部分时间的空间。

在19世纪,当社会住房开始成为一种工业业务时,一种新的房屋组织类型形成了并得到巩固。它以某种方式浮现出,功能应该被划分为一系列独立的小房间,其中一个房间会有一个水龙头——被称为洗碗间。洗碗间反过来成为一个纯粹的功能性厨房,在这个时刻,"有火的房间 "不再是一个社交场所,一个多元的的、功能性的、灵活的中央房间。工业社会将个人的聚会从厨房中移除。它变成了一个禁锢的地方。它成了一个分离和隔离的地方,特别是对妇女而言。

它仍然构成了我们所知的大多数住宅和公寓的一个无可质疑的标准。我们倾向于认为我们不再生活在按等级组织的住宅中了。然而,这种模式仍然存在,至少在我看来,一种非常简单的、不受质疑的想法仍然主导着家庭空间的组织方式。

当你邀请我的时候,我开始寻找那些提出另一种可能性以替代那些受限于固定的、功能主义的陈词滥调的住宅,并承认存在一个更加流动的空间概念。

你是如何最终选择阿尔贝托-卡拉奇的拉普拉塔内拉(西语:香蕉)宅的?

起初,对于我们谈话的主题,我想选择丽娜客波客巴迪的维德罗住宅,主要也是为了将女性的立场带入谈话。多年来,该建筑的许多图像一直伴随着我,但我也从未亲自参观过这所住宅。在进一步检查了平面图后,我意识到它实际上是一个非常有等级感的住宅。它非常清晰,有一个仆人居住的地方,一个独立的厨房,其他隔离的空间,然后才是主要的展示空间,作为代表。虽然我真的很喜欢这个项目——而且我也喜欢丽娜客波客巴迪的大部分作品——但我感觉到,从社会和空间的角度来看,传统的等级制度在这所房子里仍然非常完整。在这种特定的情况下,你很容易被巴西的亚热带植被所吸引;悬浮在森林中的高架客厅的图像,令人惊叹的家具及其美妙的布置,大窗户和外面茂盛的植被。但实话说,这并不适合作为我想谈论的话题的案例。

在那之后,我专注于阿诺客布兰德胡伯的房子,我熟悉它的空间。在过去的十年里,我一直和他工作,我拍摄了他的大部分作品。我喜欢这些建筑的原因是,你无法说出住宅在哪里停止,其他东西从哪里开始,一个工作室或一个画廊似乎是公寓的一部分,它们无法言说地融在一起。

这些住宅,如果我们应该这样称呼它们的话,它们对不同的使用模式非常开放。在他为自己建造的建筑中尤其如此,人们使用空间的方式有一种非常有趣的流动性,这取决于一天中的不同时间,那里是温暖的,还是寒冷的,以及日常的、季节性的和个人的波动。例如,柏林的布鲁纳街是一座大住宅,在一楼和二楼有一个画廊。当我第一次访问时,阿诺的办公室在二楼,三楼和四楼是他的私人空间,或他在不同时期与不同的人、朋友、客人等共享的空间。

我记得其中有一种交流,在所有的程序和目的之间,这是我之前从未在某个城市住宅中见过的。你可以两个月后再来,一切都会在不同的地方。唯一不变的是炉子。甚至厨房也是一种过渡性的空间,没有明确的厨房特征。

尽管在他的建筑中,自然和文化之间没有模糊的边界,但我非常欣赏内部空间组织方式的模糊性。在我看来,这一点在今天的建筑论述中几乎没有涉及。每个人或多或少都同意我们需要什么样的内部组织。我反对这一点,相反,我相信在这个领域有很多东西要讨论,有很多事情要做,无论气候条件如何。

所有这些例子都清楚地表明了我感兴趣的话题,并且在你第一次给我写信的时候就已经搜索过了。

我在想禁锢、住宅功能和使用的分离、预定的组织、使用的自由、流动、循环、空间的自由以及内部和外部的关系、文化和自然、有序的和直觉的。

最后我意识到,我不断地回想起一个房子。这个历程把我带到了阿尔贝托-卡拉奇在墨西哥城的拉普拉塔内拉宅。

你去过那个住宅吗?

我第一次去的时候,我甚至不知道我要去哪里。人们只是拽着我走。我们在墨西哥城,在一个本来不显眼的普通住宅区,我们经过了许多无名的小街。在某一时刻,我只记得来到一堵平凡无奇的墙上的一扇门前,我们打开门,直接进入了一个花园,那是一个客厅。我真想要弄清楚我在哪里。前一秒我还在街上走着,过了门槛后突然看到一个毛皮吊床和一个软沙发,在一个用黑色火山石铺成的院子里,在大型热带植物之间。花园的某些部分有阴影,而且有一个屋顶。这是一个室外空间,同时也是一个室内空间。

一切都很大方,看起来非常豪华,但它在材料和细节上都非常简单。主人的父亲在厨房里,一个老人,正在泡茶。在隔壁的房间里,有人正坐着写东西。在另一个角落,有一些人在非常随意地闲聊。这感觉就像一个温馨的开放空间,人们、相关的朋友或家人可以随意进出;这感觉就像一个更大的社会网络的一部分。

我记得我喜欢墨西哥城人们的社会行为方式——公共空间如何成为私人空间,反之亦然。有一个非常有趣的社区互惠的想法,关于在一起,并一起使用空间。

这可能是受气候的影响,但这绝对是一种非常典型的社会组织形式。它在拉普拉塔内拉宅的空间中得到了明确的表达。这种空间配置留在我的脑海中,而没有过多考虑建筑师或它的建造时期。它只是一个非常酷和朴素的组织空间的方式。我觉得主要的空间是在自然和文化之间。它是非常民主的,关于它与周围环境的有机关系,它的使用和人们在那里的关系。

你对互联网上这座住宅的照片有什么看法?

它们是否正确地呈现了你所经历的感觉?

我认为网站上的图片没有传达出我在那里的感觉。据我观察,大多数摄影师似乎对更大的空间的群集不感兴趣,或无法识别,似乎大多数内容专注于一些细节或形式方面--希望这一切都会同时出现。我发现了一个很长的采访,采访的对象是业主和画廊主,他们谈到了这个空间的起源。它最初是一个修道院的一部分。拉普拉塔内拉宅的结构是在预先存在的历史墙壁上,我认为这给了它某种自由。它是层叠的。

卡拉奇的住宅随机地使用和接受了现有的建筑。它被松散地组织在一个院子周围,并由小单元组成,这些单元或多或少地沿着围墙连接,所有这些单元你一进门就能看到。其中一个被用作厨房,另一个被用作餐厅,另一个被用作阅览室,等等,所有这些都被打开并朝向庭院。唯一一个全新的空间是花园后面的空间——在那些香蕉树后面,这也是该项目名称的来源。这里是业主的更为私密的区域,我猜想他们在这里睡觉。所有这些意味着我们今天讨论的住宅毫无疑问是内向的,

它没有面孔,隐藏在一堵普通的、不引人注目的大墙后面。它的内部非常自由,但毫无疑问,它也是远离公众视野的。

最为打动人心的是进入时的惊喜感吗?

我认为这并不是什么惊喜的事。更让我印象深刻的是,阿尔贝托-卡拉奇和业主似乎都不关心表现性问题。从语境来看,它有一个完全反表现性的立面。可能有一些社会方面的原因,促使某些人去寻找隐蔽性。这也是当地建筑文化的特点,是私人和公共空间关系的一个方面。当时,我认为从心理学的角度来看,对于一个建筑师和业主来说,不做一个物体,不做一个表演,不做一个地位的象征,是非常有趣的。就我而言,它是这所住宅的一个非常鲜明的特征。它不是作为一个宣言,作为一个标志,它与所有这些东西完全相反。它完全融入了。

这所住宅所为何用呢?

几乎每一个我们所知道的建筑项目都涉及到表达的主题--它的外观和它打算对世界表达什么。拉普拉塔内拉宅完全跳过了这个话题。它纯粹是关于居住的——一个社交空间。这是一个建筑师真正的去做了一个美丽的、标志性的住宅,而没有任何大惊小怪的东西。

这是一个关于室内和室外空间的住宅,关于两者之间的模糊性。那里有不同类型的室外空间。有些房间里面也有植物。你有作为房间的花园,你也有作为花园的房间。美丽。你在那里,植物在你周围生长,你必须照顾它们,这也是你为什么这么爱它们的原因。有很多层面的关系在进行。所有这些丰富的东西都悄悄地发生在一个内部化的世界,其对城市没有形式上的表现。

是否有一个回归自然的废墟的想法?

还有一件事在我脑海中浮现,我认为这也是墨西哥的特点。也就是说,无序的概念,当它不再清楚某些东西是来了还是走了,是出现了还是减少了的状态。这种无序的模糊性对我来说是墨西哥空间现实的一个极其迷人的部分。

我今天早上还想到了巴拉甘和卡拉奇之间的比较。观察两人之间的代际转换很有意思,他们都在墨西哥城建造。巴拉甘来自一个非常富有的家庭,在农村长大,骑马,了解景观和植物等,后来在生活中为墨西哥城南部的火山地区制定总体规划,明确地与这个地区的自然和火山景观合作。

然而,在他后来的作品中,花园、自然的存在,几乎总是被简化为沉思的对象。有一种二元论的想法,即人类是自然的遥远而令人钦佩的观察者,而不是自然的一部分。有一种文化——内部空间的迷人序列,然后是自然——外部。这在他自己的住宅里特别明显,巴拉甘自宅。自然环境是非常重要的,但它们是需要被控制的东西。你有一个带巨大窗户的主房间,你可以看着大自然,但你不能出去。在主房间旁边有一个小房间,它有一个非常小的门通往花园。如果你需要,你可以进入花园,但花园必须维持为外部的事物。我不知道他为什么这样做。但这一切都让人感到非常不安,极度的控制和形式上的克制。

这种控制感和分离感是今天的设计哲学中仍然显著存在的东西,但它已经不可能持续,它不再起作用了。我们需要把事情作为一个整体来思考和看待。一切都是相连的。这种热带的直觉在卡拉奇的拉普拉塔内拉宅中尤其明显。

在墨西哥城,一般来说,长在花盆里的植物和长在花坛里的植物以及在街上野生的植被之间几乎没有什么区别。这一切都交织在一起。这可以适用于很多事情,但绝对不是指控制。然而,这些二元性似乎渗透到我们文化和社会的每一个方面。在卡拉奇的房子里,这种二元性通过了很多方式得到了解决。在许多方面,它是一个非常民主的空间。

新旧之间的关系重要吗?

有时是的,有时并不重要。这一切都取决于语境。然而,建筑师和项目开发商似乎依然主要对一种被规划过的白板状态感兴趣。实际上,我对乡土建筑或非预设性的建筑更感兴趣,一种使用上自然分层的复杂性和模糊性。我觉得这需要一种更高层次的智慧,这绝对不是建立空间层次的问题。一个非常重要的层面是,你无法阐明之前的东西和之后的东西之间的区别,因为所有的东西都是一个过程,没有什么是真正新的。它更像是先有的东西,我们对它的反应,以及接下来的层次是什么,社会上的,空间上的,以及这一切是如何联系起来的。然而,有时一些新鲜的东西正是我们所需要的。拉普拉塔内拉宅不像是一种智识上的论述或练习,它只是非常的实用和有机。

我从图片中得到的印象是,材料和细节的选择思路是相当清晰的,很容易看到什么是新的,什么是既有的。我说得对么?

我认为这部分是由于存在的那种图片。当你去那里时,你不确定。而且这并不重要。细节不是你注意到的第一件事。好吧,至少对我来说,完全让我倾倒的第一件事是室内与室外,在内与在外的划分所造成的模糊性。

一切都渗透着被当地海拔压低的柔和的声音,鸟鸣,来自街道的遥远的声音,车辆经过,树叶的沙沙声和轻轻移动的阴影,阳光的色调和品质,一阵清风——所有这些都塑造了空间体验。这些都是摄影只能暗示的感觉。

作为一个与建筑打交道的摄影师,你对你的领域有什么看法?

说得极端一点,它不像一片田野(与领域语义双关),而更像一片沙漠。在我看来,大多数摄影师似乎都聚焦在事物或物体上,专注于美学或形式方面,项目被有意地孤立于它的语境和周围环境。在一个崇尚易读性的背景下,以营销为目的和方便消费而制作的图像。但事情不应该是这样的。

我认为摄影有能力容纳矛盾、复杂、模糊、多样性和不确定性——作为一种对话和论述的形式。或者至少这是我感兴趣的地方。我想对我正在看的东西含糊其辞——或者直接与矛盾和含糊的情况一起工作。这最终,在某些方面,与建筑有关,但它不是关于建筑的。

你是如何得出这种认知的?

我一直知道,甚至在我能用语言表达之前,我对空间的一致性和我们如何体验空间感兴趣,不管那是什么,或者它是如何表现的——在我们存在于世界的最大意义上。

我开始于一个艺术学校的工作室,对空间处理方法的另类叙述相当感兴趣和关注。我们看了很多AA当时正在做的事情,它是非常实验性的。

没有规程,同时也确实有一个规程。它必须发挥作用。你需要 "设计",并有标准使其发挥作用。我总是觉得,在空间中还有其他的东西,不仅仅是关于功能。对我来说,它是关于社会、空间甚至情感的体验。我想要找出我们可以如何谈论这个问题。

作为荷兰皇家艺术学院(Gerrit Rietveld Academie)的学生,我邀请雅克-赫尔佐格参加一个公开会议。雅克来了,并说了些话。我想,好吧,也许有一个办法。他说了非常有趣的事情。当时我不知道该往哪儿看。雅克也是一种邀请,他说 "当你毕业时,到我们这里来"。而这基本上就是我所做的。我想我是第一个在赫尔佐格与德梅隆事务所那里工作的外国人。但我的背景和兴趣让我对瑞士建筑实践的现实和严格性准备不足。我不知道如何建造。这是一个严重的问题。我不了解所有的技术内容,但我仍然觉得有一些有趣的事情在发生。我花了一些时间来连接所有的点,这就是我如何发现摄影作为一种媒介,以我自己的方式参与进讨论,而不需要建造。

毕竟我在自己的道路上,试图找到一种方法来沟通和处理这些经验。客观地说,在空间中发生的事情太多了,或者说我们所经历的事情,不仅仅是建筑。为什么我们只谈论建筑? 建筑是对话的一部分,但它不是对话的终点。

2022年7月28日

エリカ・オーフェルメール: 家や住まいというものは、意味の広い概念ですよね。ですから、住宅として何を選ぶかよりも、まずは自分自身に問いを投げかける必要がありました。住むとはどういうことなのだろうか?私はどうやって生きるのだろうか?どのようにして社会が建築を形づくるのだろうか?こういった問いへの探求が、私に考えさせる時間をくれました。自分の家や、かつて訪れたことのある家、本やインターネットで見たことのある家などを見てみることにしました。

何を評価基準とされたのですか?

私は、都市空間を形成する社会構造と、そこで生じる自然環境との関係に常に興味を持っていました。また、時代と共に、洞窟の中の火が住居の中へと移動し、そして、住居の中から都市の中へと移動していったことを考えたのです。

もともと暖炉というものは、人の集まる装置でした。食料を交換し、蓄える場所として。心地良い避難所として。それに遊び場として。社会的慣習もそうやって人が集まることで発展したものです。産業革命以前のキッチンとは、火のある部屋のことであり、みんな仕事終わりにはそこでほとんどの時間を過ごしたのです。

19世紀は、ソーシャルハウジングが産業のビジネスへと変化し始めた時期です。その新しいタイポロジーは、家がどうあるべきかを明確に固定してしまうようなものでした。どういうわけか、機能は独立した小さな部屋に分割され、そのうちの一つに蛇口がつけられました。そこがスカラリーと呼ばれたのです。そうして、スカラリーは純粋に機能的なキッチンとなりました。その瞬間に「火のある部屋」は、社交のための場ではなくなりました。かつては、フレキシブルな家の中心として、複合的で機能的な部屋だったのですよ。

産業社会によって、キッチンに人が集まることはなくなりました。キッチンは監禁の場所、つまり分離と隔離の空間となりました。特に女性にとってはね。

そのことは、私たちのよく知る多くの戸建てや集合住宅において、今でも揺るぎない基準となっています。私たちの住まいが、ヒエラルキーで組織化された家であるとは、誰も思いません。ですが、実際は依然としてそういったものが残っているのです。とても単純で疑問の余地もないような考えが、実は、家庭空間のあり方を支配している。少なくとも私にはそう思えるのです。

このインタビューへの誘いを受けて、凝り固まった紋切り型の機能主義に対するオルタナティブとして、流動的な空間のコンセプトをもった住まいを探し始めました。

アルベルト・カラチのラ・プラタネラを選ばれたのはなぜですか?

最初は、会話のトピックとしてリナ・ボ・バルディのバルディ邸を選ぼうと思っていました。特に女性の話を持ち込むにはいいだろうと。その建物のイメージが、私の頭の中には何年もの間残っていたのです。ついに訪れることはなかったのですが。ところが、平面図をよく見てみると、実はかなりヒエラルキーの組織化された住宅だと気づきました。とても明解に作られています。召使いの住む場所があり、独立したキッチンがあり、その他にも分割された空間があり、そしてディスプレイとしてのメインスペースがある。つまり表現としての空間です。とても好きなプロジェクトですよ。リナ・ボ・バルディの作品はどれも大好きですし。ですが、社会的、あるいは空間的な視点から見るとこの住宅には、伝統的なヒエラルキーがそのまま強く残っているんです。こんな特別なシチュエーションの中では、ブラジルの亜熱帯植物にすぐに目がいってしまいますよね。森の中に吊り下げられたリビングルーム。素晴らしい家具たちの美しいまとまり。大きな窓に青々とした外の緑。ただ、これらは私の話したかった内容とは関係のないことです。

その後、私のよく知るアルノ・ブランドフーバーの住宅と、その空間に着目してみました。彼とは10年以上の付き合いですし、彼のほとんどの作品を写真に撮ってきました。それらの建物は、どこから始まってどこで終わっているかが、よくわからない感じで好きなんです。スタジオやギャラリーも住居の一部のようになっていて、不可解な形で溶け合っています。

これらは、言ってみれば、多様な用途に開かれた住居ということなのでしょうか。彼の自邸において特に顕著なことですが、時間帯の変化や、場所による寒暖の変化、日常あるいは季節的な変化、そして個人の気持ちの変化など、いろいろ変化によって空間の使い方が変わっているのです。この流動性はとても面白いですね。例えば、ベルリンのブルネン通りにある大きな住宅は、地上階と2階にギャラリーがあるのですが、私が訪れた時、アルノの事務所は3階にあって、4階と5階は彼のプライベートスペースとして、彼の友人やゲストなどの様々な人と過ごすことのできる空間になっていました。

あらゆる機能と目的とが入れ替え可能になっています。そういった形の都市の住宅は見たことがありませんでした。二ヶ月後には、あらゆるものが違う場所に配置されていることもあり得ます。同じ場所にあり続けるのは、ストーブだけ。キッチンでさえキッチンらしい設えがなく、移動可能な空間になっています。

彼の建築には、自然と文化との境目がなく、その内部空間の作る曖昧さは素晴らしいと思います。今日の建築的議論の中では、あまり取り上げられていないようなことだとは思いますが。内部空間がどうあるべきかについて、みんなそんなに疑問を持つことはないのでしょう。ですが、私は逆にもっと議論すべきなのだと思いますし、いろんな取り組みがなされるべきだと思います。それは風土とは、関係のないことだと思います。

あなた方からのインタビュー依頼を受けて、私は、こういったことに興味を持ち、探求していたのだという事が改めて明確になってきました。

住宅内での監禁的状態、機能や用途の分離、決まりきった組織化の方法。そういったことに対する、用途の自由さ、空間の流動性や回遊性、そして自由度。内部と外部、文化と自然、秩序と直感との関係性。これらは、私が考えてきたことです。

そして、結局いつも同じ住宅のことを考えていたのだと気づきました。メキシコシティにあるアルベルト・カラチのラ・プラタネラです。

そこには、行かれたことがあるのですか?

そこへ初めて行った時は、自分がどこへ向かっているのかもわからないような状態でした。ただ、連れられて。メキシコシティの、とりわけ特徴のない普通の住宅街にある小さな脇道を抜けて行きました。あるところで、ドアの前に到着したことを覚えています。のっぺりとした、なんてことはない壁面につけられたドア。そこを開けると、すぐに庭の中に入っていることに気づきました。しかも、そこがリビングでもあったのです。私はどこにいるのだろうか、と考えざるを得ませんでした。歩き出すとすぐに、ある領域に入ったのがわかりました。突然、大きな熱帯植物の間から毛皮のハンモックや柔らかなソファが見えてきました。それらは、黒の火山石の敷き詰められた中庭に置かれていました。庭の中は、所々に影が作られ、屋根のかかっているところもありました。そこは外部空間でもあり同時に内部空間でもあるような場所でした。

あらゆるものが寛大で、そしてラグジュアリーに見えました。ところが、素材やディテールはすごくシンプルなのです。キッチンにはオーナーのお父さんがいました。とても高齢の方でしたが、そこでお茶を入れていました。その横の部屋では誰かが座って書き物をしていて、また別のコーナーではガヤガヤと雑談している人たちがいました。とてもウェルカムで開けた家でした。友達や親族、あるいは家族が勝手にやってきて、また出ていくというような、大きなソーシャルネットワークの一部のような場所だと感じられました。

メキシコシティでの人々の社会的な振る舞い方が、とても好きだったことを思い出します。パブリックスペースとプライベートスペースが入れ替わるような振る舞い方です。人と一緒に空間を共有する際のコミュニティが持つ相互扶助的な考え方が、とても興味深いのです。

気候がそうさせるのかもしれませんが、それが典型的なこの社会の組織化の方法であることは間違いありません。そういった点から考えると、ラ・プラタネラの空間は理解しやすいでしょう。誰が作ったとか、どの時代だとかは関係なく、この空間構成は、私にとってはとても印象深いものでした。ただクールで、気取りのない空間構成。メインスペースは、自然と文化との中間にあるような空間に感じられましたし、周辺環境や空間の使われ方、そしてそこにいる人々との有機的な関係性は、とても民主的なものでした。

インターネットで見られるこの住宅の写真についてはどう思われますか?そこに、経験されたようなことは表現されているのでしょうか?

ウェブサイトにある写真では、私がそこで感じたようなことは伝えられていないと思います。私が見てきた多くの写真家は、空間の構成を俯瞰して捉えることができないのだと思います。あるいは、興味がないのでしょう。ですから、大抵はディテールや形式的な側面に焦点が当てられています。本当は、それらが統合されるべきなのだと思いますが。この家のオーナーであり、ギャラリストである方へのロングインタビューの記事を見つけました。そこで、この家の起源が語られていました。もともとは修道院だったそうです。ラ・プラタネラは、その既存の歴史的な壁の上に新しく作られたのだと。この自由な感じはそこから生まれているのだと思います。歴史のレイヤーが積み重なっている、ということですね。

この住宅は、既存の建築を適度に受け入ながら利用しています。周囲の壁面に沿って、小さなユニットが緩やかに中庭を囲っていますね。中に入ると、そのことがすぐにわかると思います。一つはキッチンとして使われていて、その他はダイニングルームや、読書室などに使われています。全てが中庭に向かって開いています。庭の奥には、ここで唯一の全く新しく作られた空間があるのです。それはプラタナスの木に隠されています。プラタナスの木は、このプロジェクトの名前の由来となっていますね。ここがオーナーのプライベート空間になっていて、ここで寝たりするのでしょう。つまり、今議論しているこの住宅は、実は紛れもなく、内向的な性質をもっているということです。

顔がなく、のっぺりとした巨大な壁の後ろにあるのは、内部の自由さと、公共の目からは全く閉ざされた世界、というわけです。

入った時に感じる驚きが、最も印象に残っていることでしょうか?

驚きということよりは、アルベルト・カラチもクライアントも表現ということに対してあまり興味がなさそうな事が、とても印象的でした。このファサードなんて都市の中でも全く無表情なものです。何かの社会的側面が、こういった特定の人々をインビジブルなものへと向かせるのでしょうか。あるいは、それがここでの建物の文化、つまりプライベートな空間とパブリックな空間との関係性における特徴なのかもしれません。建築家やオーナーは、ステータスの象徴としてのオブジェを作ったり、それをひけらかすようなことを控えている。その心理的な側面にも興味を持ちました。この住宅はそういったこととは真逆で、ステートメントやアイコンとして作られているわけではない。そのことが逆に強烈な個性となっています。周囲に完全に溶け込んでいますね。

この住宅はなんのためにあるのでしょうか?

私たちの知っているような、ほとんど全ての建築プロジェクトは、表現の問題と関わっています。つまり、世界に対して何を表現するのか、ということです。ラ・プラタネラはこういった表現の問題を完全にスキップしていて、つまり純粋に、住まいであるということです。そして社会的空間である。建築家は、無駄なことなど言わず、本当に美しい住宅を作ったのです。

内部と外部、そしてその二つの曖昧さ。さまざまなタイプの外部空間。植物の置かれた内部空間。部屋としての庭。庭としての部屋。美しいでしょう。植物は育ってきますから、手入れをしなくてはいけません。だからこそ愛おしく思える。植物との関係性はさまざまですが、これら全ての豊かさは、内面化された世界においてひっそりと育まれるものです。都市には背を向けたまま。

自然によって廃墟化することで、生き生きとしてくるといったことも考えられますか?

そういったことも考えていました。とてもメキシコ的な特徴だと思います。つまり、ここではエントロピーの考え方が特徴的で、来ているのか去っているのか、増えているのか減っていっているのか、そういったことがもはやわからなくなる。このエントロピーの不明瞭さが、とても面白い。それがメキシコ的空間のリアリティなのだと思います。

今朝もバラガンとカラチの違いを考えていました。この二人の世代的な違いを見てみるのも面白いと思います。二人ともメキシコシティで作っていますよね。バラガンは裕福な家庭で生まれ、田舎で育ちました。馬にも乗っていたのでしょう。ランドスケープや植物などのこともよく知っていました。後にメキシコシティの南部にある火山地帯のマスタープランを計画していましたね。火山と自然のランドスケープとの関係がよく考えられたものでした。

ところが、彼の後期の作品では、庭、つまり自然の存在が小さくなっていきます。自然は、ほとんど瞑想のための対象物となってしまいました。人間は自然の一部ではなく、それを観察し賞賛する遠く離れた存在である、という二元論的な考えが見て取れます。文化的なのです。魅力的な内部空間のシークエンスがあり、自然がある。でもそれは、外部としての自然だということです。彼の自邸、バラガン邸ではそのことが顕著に見て取れます。自然環境はとても重要な役割を果たしてはいますが、自制すべきものとして扱われているのです。巨大な窓のあるメインルームからは、自然を見ることはできますが、外へ出ることはできません。庭へ出るには、メインルームの脇にある小さな部屋の、さらに小さなドアから出ていくのです。必要となれば、庭へは出ることができる。ところが、基本的には、庭は外にあるべきだということです。彼がなぜそうしたのかわかりません。とても窮屈に感じますし、極度にコントロールされていて、堅苦しく拘束的な感じがします。

こうした支配と分離といった感覚は、現在の哲学においても未だ根強い感覚だと思います。しかし、それを維持することはもはや不可能で、機能するものではないと思います。私たちは、物事を全体として見るべきなのだと思います。全ては繋がっているのだと。こういった熱帯的直感が、カラチのラ・プラタネラには表れていますね。

メキシコシティでは、鉢や花壇から育つ植物と、道から自生する植物との間には、ほとんど違いが見られません。全てが絡み合っている。これは、いろいろなことへ応用できる考え方だと思います。支配的な考えとは全く異なるものですよね。今でも二元論的な考え方は、私たちの文化や社会のあらゆるところに浸透していますが、このカラチの住宅では、その二元論的な考え方がさまざまな方法で解決されてるのです。民主的ですよ。いろいろな意味でね。

新旧の関係が重要だということでしょうか?

そうだとも言えますが、関係ないときもありますね。コンテクストによるでしょう。建築家やプロジェクトの開発者の多くは、わかりやすく計画されたタブラ・ラーサに興味を持つようですが。私は、土着的な、あるいは控えめな建築の方に興味がありますね。自然な形で階層化された複雑さを持っていて、用途に多義性をもった建築です。それには、高い次元での知性が必要だと思います。それは、空間的なヒエラルキーを作るということではないですよ。以前からあったものと新しくできたもの、その違いが明瞭に示せないことこそが重要なのだと思います。全てが過程であって、新しいものは何もないのだと。何かから始まって、それに答えて、その次がまたやって来て、というような形で、社会的にも空間的に全てが繋がっているのです。時には、フレッシュで本当に新しいものが必要とされる時もあると思いますが。ラ・プラタネラは知的なディスコースでもエクササイズでもありませんね。実利的で有機的なものです。

私が写真を見た印象からは、素材やディテールの選択が極めて明快で、新旧の区別もすぐにわかったくらいです。私が変なのでしょうか?

おそらく写真のせいだとは思いますが、行ってみてください。新旧の区別は難しいと思います。でもそんなことはどうでも良いでしょう。最初に目につくのは、ディテールではないと思います。そうですね。少なくとも私にとっては、内部と外部の表現によって生まれる曖昧な領域には、目眩を覚えました。

標高の高さから生じる鈍く柔らかな音、鳥のさえずり、通りから聞こえる遠くの声、通り過ぎる車、さらさらと優しく揺れ動く葉の影、太陽光の素晴らしさ、そのトーン、小さなそよ風、それら全てが浸透しあって、空間の経験を形成しています。こういったことは、写真だけが仄めかすことのできる感覚です。

建築に携わる写真家として、ご自身の専門分野に対しては、どのようなことをお考えですか?

極端に言えば、分野といっても砂漠みたいなものですよ。ほとんどの写真家は、事や物に集中して、美的で形式的な側面に多くの焦点を当てています。そして、プロジェクトはそのコンテクストや周囲の環境から意図的に隔離されてしまっています。広告目的で作られ、わかりやすさが賞賛される環境の中で、容易に消費されてしまうイメージたち。そういった写真のことではないのです。

写真には、矛盾や複雑さ、曖昧さや多様性、そして不確かさを維持する力があると考えています。それは、ダイアローグとディスコースの形式ということでしょうか。少なくとも、私の興味はそこにあります。私は、私の見ているものに対して曖昧でありたいと思っていますし、相反的で両義的なシチュエーションに対して真っ向から取り組みたいと思っています。そういったことを思っていると、どうしても建築が関係してきます。それこそが建築であるということではないですが。

どのようにして、こういった認識に到達されたのですか?

言葉にする前から、わかっていたのだと思います。私は、空間の一貫性や空間の体験といったものに興味を持っていました。それがどんなものであるのか、何が表現されているのか、は関係ありません。私たちが世界の中にいる、というとても広い意味での興味です。

私が美大のスタジオ課題に取り組み始めたときのことです。スタジオでは空間的なアプローチに対する、代替としてのナラティブに関心が向けられていました。当時は、AAスクールがしていたことをよく見ていました。とても実験的なものでした。

課題としての実施要綱はないはずです。でも実際にはあるも同然だったのです。機能しなくてはいけないですから。「設計」しなくてはいけなかったですし、それが機能するための基準もありました。私は、機能だけではない何かが、空間にはあるのだと感じていました。私にとってそれは、社会であり、空間的で感情的な経験のことでした。どうすれば、そのことを議論できるのか考えていました。

私は、リートフェルトアカデミーの学生として、ジャック・ヘルツォークをパブリックカンファレンスに招待しました。彼は来てくれて、話をしてくれました。道が開けた感じがしました。彼の言っていたことがとても面白かったのです。当時、私は、どこへ向かえばいいのかわかっていませんでした。そんな時に「卒業したら、うちに来てよ」とジャックが誘ってくれたのです。私のしてきたことは、基本的にはそれだけです。私が、ヘルツォーク&ド・ムーロンで働いた初めての外国人だったと思います。ところが、私のそれまでの経験や興味だけでは、スイスの建築実務の厳しさや現実を受け入れる準備ができていませんでした。建てる方法がわからなかったのです。深刻な問題でした。技術的なことは何一つわからなかったのですが、何か面白いことが起きているということだけは感じられました。全ての点を結びつけるには、しばらく時間がかかりましたが、こうして、建物を建てずとも、自分の言葉で議論に参加できるメディアとして写真を発見できたのです。

こういった経験を通して、コミュニケーションや仕事をする方法を模索しつつも、私は私の道を切り開いていきました。考えてみれば、建築の中に限らず、空間の中や、私たちのこうした経験の中では、もっともっといろんな事が起きています。なのに、なぜ私たちは建築のことだけを話しているのでしょう?建築は会話の一部であり、それが全てではないでしょう。

2022年7月28日

Erica Overmeer: A house or a dwelling are very broad notions. I felt, that before making a choice, I needed to confront myself with questions like: What is it to dwell, how do I live? How does society shape what we are building today? The time spent exploring these questions, got me thinking in ways that I had not tried before. I looked at my own house, the houses I had visited, the houses I knew only from books or the Internet.

WHAT WERE YOUR CRITERIA?

I have always been interested in the relationship between the social structures that define urban spaces and the natural settings where they appear. I also thought about how over time the fire moved from a cave to a dwelling, from a house to a city.

Since the beginning a fireplace has been instrumental in gathering people, in the exchange and preparation of food, comfort, shelter, play, and the social customs that developed out of being together. Before the industrial revolution the kitchen - the room with the fire, was the space where the majority of people spent most of their time after the work was done.

In the 19th century, in the moment when social housing started to be an industrial business, a new typology crystallised and consolidated on how a house should be organised. It somehow emerged that functions should be divided between a series of small separate rooms and one of them would have a water tap - and be called a scullery. The scullery in turn became a purely functional kitchen and in this very moment „the room with the fire” stopped being a social place, a plural, functional, flexible central room. Industrial society removed the meeting of individuals from the kitchen. It became a place of confinement. It became a place of separation and segregation, especially for women.

It still constitutes an unchallenged standard for the majority of houses and apartments we know. We tend to think we no longer live in hierarchically organised houses. However, this model still persists and, it seems to me at least, that a very simple minded, unquestioned idea still dominates how domestic spaces are organised.

When you invited me, I started to look for dwellings that proposed an alternative to a fixed, functionalist cliché and acknowledged a more fluid concept of space.

HOW DID YOU END UP CHOOSING THE ALBERTO KALACH’S LA PLATANERA HOUSE?

At first, for the topic of our conversation I wanted to choose Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro, notably also to bring a female position to the conversation. Over the years, many images of the building had stayed with me, but I had also never visited the house in person. After further examination of the floor plans I realised that it is actually a very hierarchically organised house. It is very clear, there’s a place where the servants live, a separate kitchen, other segregated spaces and then the main space of display, of representation. Although I really love this project – and I love the work of Lina Bo Bardi in general – I had the feeling that from a social and spatial point of view, traditional hierarchies where still very much intact in this house. You can easily be distracted by the sub tropical vegetation of Brazil notably in this specific situation; the images of the elevated living room suspended in the forest, the beautiful configuration of the amazing furniture, the big windows with the lush vegetation outside. In truth, this was not going to work as an example for what I wanted to talk about.

After that, I concentrated on the houses of Arno Brandlhuber, spaces that I know well. I’ve been working with him for the last ten years and I have photographed most of his work. What I like about these buildings is that you cannot say where the house stops and something else starts, a studio or a gallery seems to be a part of an apartment, they melt together inexplicably.