イラ・ベカ&ルイーズ・ルモワンヌ: 森山さんは、人生の大半を母親の経営する酒屋で働いていました。その母親が亡くなった時、家と酒屋を取り壊して、まったく同じ場所に新しく家を建てることにしたのです。彼は自分を実験台とする思いで、建築家、西沢立衛に直接手紙を出しました。彼こそが、今と変わらない生活に、新たなチャレンジを与えてくれるプロフェッショナルとして適任だと思ったのです。イラは、日本のノイズミュージックが好きだという共通点から森山さんと仲良くなり、2017年の夏に1週間ほど、彼の家に滞在させてもらったんです。

森山さんの以前の生活はどういうものだったのでしょうか?

元の家は、西沢さんが教えてくれたことから想像するに、部屋は、本で埋め尽くされた棚で覆われていて、窓がなかったようです。コンパクトで閉鎖的で、どちらかというと陰気な生活でした。森山さんにとって家を建てるとは、ある意味、彼の生き方を新しくすることでもあったのです。オタク的で、埃っぽく、窮屈な生活から、都会の小さな森の中で生活する野良猫のように彼の生活は激変したのです。

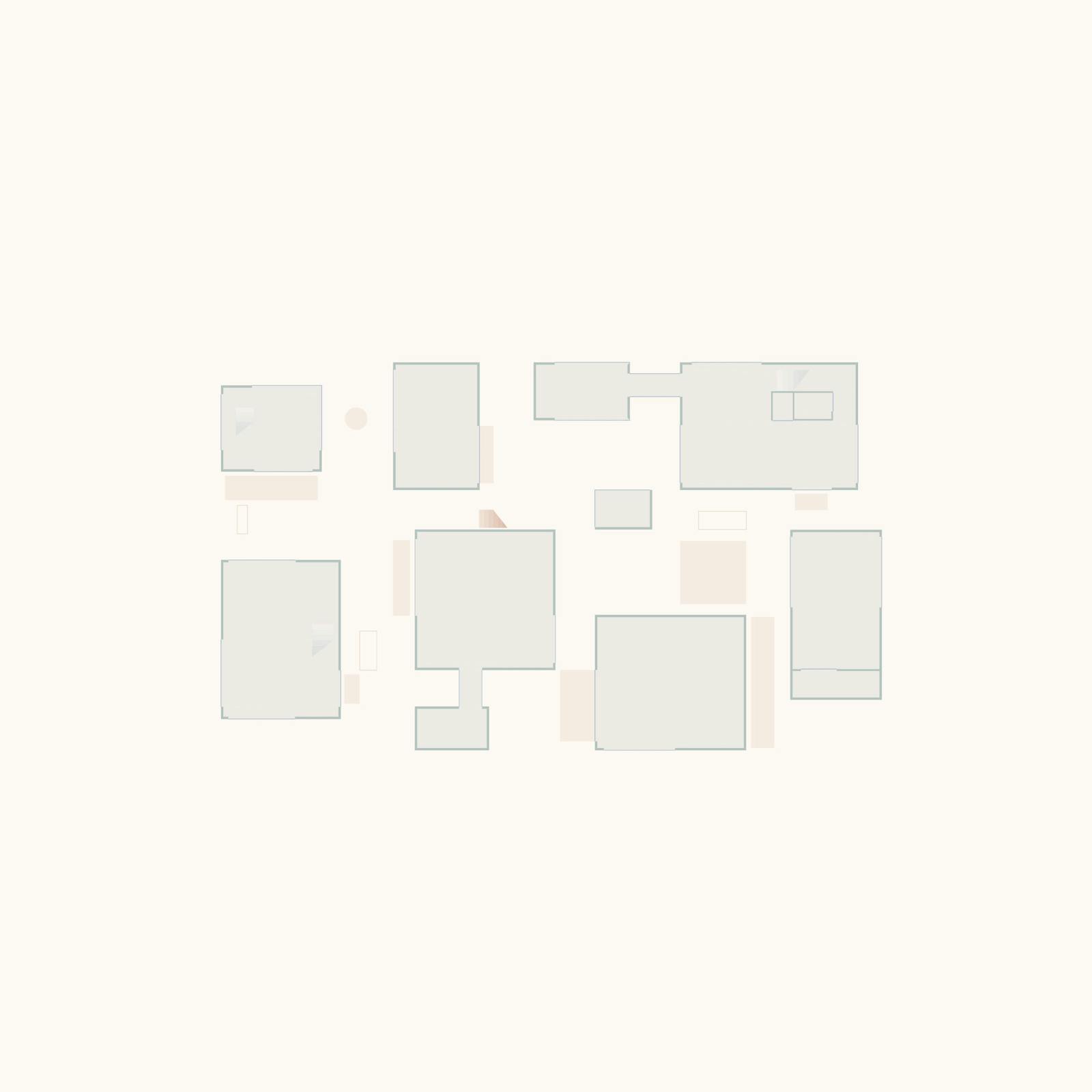

現在の彼の生活空間は、小さな敷地に散らばったそれぞれの住戸に分かれています。一層だけのものもありますし、上の階へと登れるものもあります。地下にあるものもありますね。雨の日も、雪の日も、風の強い日も、登ったり降りたりしながら、屋外にあるそれぞれのキューブの間を移動しなくてはいけないのです。キッチンやバスルームに行くには、外に出ないといけないですしね。このように生活空間が断片化された構成は、型破りで驚くような状況を提起するものです。

一般的な住宅においてリビングとして考えられる空間、つまり個々の独立した部屋をまとめる中心的な空間は、中央の小さな庭が担っているのです。そう、小さなユニットをまとめあげているのは外部空間だということです。

森山邸にいるときには、守られているような感じはありましたか?それとも都市に対して晒されているような感じがありましたか?

西沢さんと撮影した映画『Tokyo Ride』で彼は、社会の中で、自己を保護する、あるいは露出するという概念に対しての日本人と西洋人との行動の違いを、ユニークな視点から提起しています。西洋人は、たいてい個人の強さに基づいてアイデンティティを築いていくので、力強く見えることは、必要なことですし、対立的な社会的関係にも備えておく必要があるのです。非常に好意的に、そして外交的に振る舞うことができるのですが、そんな際にも常に、無意識にも、権力の力関係が作用している潜在的な対立を社会的な相互作用としてイメージしてしまうのです。それに対して、西沢は、日本人は「武装解除された」状態なのだと説明します。相手との相互作用によって生まれる対立的圧力に動機付けられた存在ではないということです。それは日本の都市に攻撃性がほとんどないことからも強く感じられることでしょう。日本の現代建築に見られる透明性へのアピールもそれが理由なのかどうかは、わからないのですが、関係性をもっと調べるのは面白いかもしれませんね。

建築における保護と露出という点では、日本での一般的な断熱の扱いには、とても驚きましたよ。日本は、高温多湿な気候なので、伝統的に建築は多孔性のものだと捉えられているのです。そうすると建物内での自然換気も可能ですから。さらに驚きなのは、この熱に対する多孔性という考えが今日においてもまだ残っているということです。壁は、たいてい薄くて脆く、室内にいても温度や音という点では、外と近く繋がっているように感じられるのです。冬はとても寒く、夏はとても暑いということです。

しかし、このことは、自然への興味や敬意と関係していることだと思いますし、それが日本文化の強みでもあると思います。

これは、とても面白い問題ですね。プライバシーや他者へのリスペクトは、それを定義づける文化的なルールに関連することですよね。

プライバシーの問題は、基本的に文化的な定義によるものですし、国によって捉え方は大きく異なります。例えば、コペンハーゲンでビャルケ・インゲルスの『8 House』の映画を撮影していたとき「晒された親密さ」という逆説的な考え方を経験したのです。デンマークでは冬の間、自然光が少ないこともあり、光への関心が高く、大きな窓にもカーテンをしない人が多いのです。だから夕方になると、通りすがりの人が、家の中で起きていることの全て、例えば家族の親密な集まり、寝室での様子など、を見ることができてしまうのです。この点では森山邸はとても似ていますね。大きな開口部があって、それによって内部と外部が混ざり合っている。日本にもデンマークにも、互いを尊重する文化があるからうまくいくのでしょう。通り過ぎる人、自転車や車に乗っている近所の人、走っている子供、歩いたり、立ち止まったりしているお年寄りなどを、絶え間なく流れるように1日中、見ることができるのです。ただし、覗き見をしてはいけないことになっているのです。実際に、覗き見してくるのは、外国人だけだと森山さんは話をしてくれました。中にはかなり失礼な人もいるみたいですが。それを避けるためにも、道に英語で書かれたボードを立て掛けて、観光客には、庭のプライベートエリアに足を踏み入れないようにお願いしているのです。

道路側への大きな開口部は、透明性を作り出しているのですが、西沢さんの意図は、住人を都市から少し切り離し、中央の小さな庭を利用しながら、平和で守られた場所を作り出すことにあったのです。それは、よくバランスのとれた奇妙な方法で達成されています。切り離してしまうのではなく、また完全に晒された状態でもなく。常にどちらにも選択肢がある状態で、それがとても心地よいのです。

ヨーロッパでは、自然との繋がりや調和を考えるときに、たいてい自然素材を使った建物を想像してしまうのですが、森山邸は抽象的な白いボックスの集合体ですよね。これにはどのような効果があるのでしょうか?

この場合、建築は自然とつながるための装置であって、必ずしも自然そのものの一部ではないということです。素材はレトリカルな意味を持っていませんし、言語的にも、家は道路側より庭の方に属しているのだ、とはっきり語っているものでもないのです。この住宅は、ミニマルで贅沢さの象徴などありません。主な目的から気が散らないようにしているのです。家具や設備に関して言えば、森山さんが生活する上での最低限のものは揃っています。例えば、キッチンは主にビールを冷蔵庫に入れるためだけに使われるものであっても、大勢のお客さん、あるいは彼自身のためにたくさんの食事を作るためのものではないのです。私たちが寝室と呼ぶようなものもありません。いや本当に、床に寝るのはとっても過激な体験でしたよ。

私たちの捉え方は、あなたの言う通り、この家は、ボックスの集合体なのです。小さな部屋、そして空間と今この瞬間を楽しむという考えです。あらゆるニーズに応えるような技術的な装置でもないし、イデオロギーの表明でもないのです。シンプルでミニマルな方法によって、全てうまく機能しています。住居としての機能を超えて、森山さんの暮らすこの家は、空間、庭、そして通り過ぎる人々の動きから生じる繊細な相互作用によって生まれる感動が、体験できる場所なのです。

映画にとって、なぜ家が興味深いテーマなのでしょうか?

建築に関する映画のほとんどは基本的に、建物の美的特徴や素材、構造、色々な革新的な機能などに焦点を当てた説明的なものであることに、私たちは早い段階で気づいていたのです。

一言で言えば、建築映画は、建築家のプロモーションやコミュニケーションツールとしての役割を担っている事が多く、映画の作り方は、必然的にある種の美学が誘発されてしまうのです。そのことに対抗して、私たちは、映画と建築の間の従属関係を歪めることで、建築がどのように表現され得るのか、という議論を展開する真の自由を見出そうとしてきたのです。映画は、私たちが人間として周囲の空間とどのような関係を築いているのかを問いかけてくれるのです。そういったことから、私たちの主な取り組みは、建築的表現の最前線に人間を配置し、建築の役割や影響をもっと人間学的な視点から問いかけることとなったのです。だから私たちは家を選ぶのでしょう。感情や記憶、そして親密さで満たされたような空間は、家以外には存在しません。家が最も面白くナラティブな装置なのです。家は空間としての現実でありながら、精神的な領域でもあります。この心理的な豊かさによって、家は、個人的で感動的な物語の無限の貯蔵庫であるということを理解するのです。

では映画『Moriyama-San』は、家についての映画なのでしょうか?それとも人についての映画なのでしょうか?

私たちは、所有者や建築家は、プロジェクトに関わりすぎていて感情的になっているので、いつも撮影しないようにしてきたのです。彼らは劇場で演技しているみたいになってしまいますし、自然に、演出的でなく建物について話せるほど十分な距離感を保てるケースはほとんどありません。

森山さんは例外でした。彼は、いわゆる典型的な所有者としてのプライドを見せつけたりはしないからです。西洋的な個人であれば、もっと社会的な見栄を張ってしまうのですが。逆に、彼はとても自然で、無頓着なのです。建築として認められた建物の所有者としては、常識を逸脱した無頓着さです。

彼が素晴らしいのは、純粋で個人的な楽しみのために、自分の家を面白がっているように見えることですね。すごくユニークなことですよ。

その空間での生活や経験を通して、その空間について話そうとしているのですが、それはつまり空間との物理的、心理的な相互作用が重要だということです。抽象的に空間の質を語るのではなく、そこに住む人が空間とともに作り出す、知覚的で感情的な関係性から、その特質を探求していきたいのです。森山さんはその点では群を抜いて特別な存在です。私たちは天啓を得たのです。微小な気温の変化や、忙しい都市生活の中ではほとんど気にかけないような事にも気づけるような、とても繊細で洗練された感性に、これほどまでに密接にそして親密に触れた経験は、ほとんど初めてのことでした。とても新鮮なものでした。彼の感性は確かにとても日本的なものだと言えるのですが、初めての日本文化との関わりでしたので、日本人の感性の受容性にはとても驚きました。森山さんが家中を動き回っているのは、映画のあらゆるシーンで見ることができると思います。光や音や風、それに温度の質などに合わせて、座ったり、寝転んだり、留まったりする場所を選んでいるのです。機能的な必要性からというより、知覚的な直感に導かれるようにして、建物の中を移動していくのです。単純にすごいでしょう。私たちにとってはとても啓発的な出会いでしたし、彼の超高感度な感性からはたくさんのことを学びました。空間を物語るための最良の方法は、空間への完全な没入とそこでの親密な体験を得ることであるという私たちの確信はより強いものになりました。そしてそれこそが、まさしく映画が可能にしてくれることなのです。

森山邸ではどんな体験を得られましたか?

家のスケールにはとても驚きました。あらゆる空間がとても小さいのです。中に入るには身体を調整しなくてはいけないですし、動くときは正確に慎重に動かなくてはいけません。正確なコレオグラフィーのように空間との物理的な対話が求められます。そうしないと、いろんなものに当たってしまいますし、動く度に家具やオブジェを倒してしまいます。だから、動くときや歩き方には細心の注意が必要です。家もかなり危険ですよ。フェンスや手すりもないですから。穴や大きな開口部、それにとても小さな梯子なんかはあるのですが。常に警戒が必要なフィジカルなプレイグラウンドみたいなものでしょうか。場所によって状況が異なっていますし、その都度、異なる意識が必要です。この家は、感覚の万華鏡のようなものですね。

西洋の成人として初めに感じたことは、身体があまりここに適応できていないということです。広い空間の方が慣れていますから。それに日本の家の小さな寸法に合わせられるほど、正確な身体の動きをマスターできていないのです。西洋では建築家が安全に気を配ってくれている事は当たり前ですから、こういったことに注意を払っていなかったのです。私たちの身のこなし方は、物理的にもがっしりしていて、荒々しいのだと感じました。そこにいると私たちの身体的言語が再教育されているように感じるのです。小さい頃から日本人は、スケールの制約に適応するように訓練されていて、自分の動きをもっと慎重にコントロールできるのでしょう。

人がどのようにその空間に存在しているのかを観察することで、その空間の真実を理解できると言うことでしょうか。

「真実」と言うよりは、「内実」という感じでしょうか。この私たちの直感は、AAスクールでの指導での方針にもなっています。修士学生のスタジオを持っていたのですが、タイトルを「感覚的観察者のラボラトリー」としたのです。このコースでは、観察力を高めるための道具や方法を発展させ「見る技術」を紹介していくことを目的としていました。より大きなスケールでは、私たちの社会的行動から読み取れる文化的特徴だけでなく、都市生活に作用している政治的、経済的な力への理解と感度を高めることを目的としています。

社会文化的、そして歴史的要素が複雑化する中で、質の高い観察力や、敷地へのシャープな分析力がいかに重要なことであるか気づいてもらう事を意図していました。これらが、若い建築家としての将来の提案を、人間的で力強い感受性とともに、より正確な、そして適切なものにしてくれるのだと思っています。

現代において、観察力が弱まってしまっているとお考えですか?

私たちは、加速的な時代に生きているようですね。生産性や効率性、そして目的へと直行することへの大きな圧力があるわけですが、何かを理解するために時間を使ったり、何がどうなっているのかを考えたり、注意深く考える、といったことへの価値が減っているのだと思います。このことは学生にも見られます。形を作ったり、目標を達成することに関してはとてもモチベーションが高いのですが、じっと考えたり、不思議に思ったりすることへのモチベーションが低いのです。いや、そういった事ができないのかもしれない。どんなものであれ、彼らはすぐに何かを達成しようとしてしまう。こういった加速的な流れは、周囲のものへの可能性や注意力を低下させてしまうのです。

私たちは、まさに技術に魅了された時代に生きているわけなのですが、クレイジーな事ですよ。この20年、30年を考えてみて下さい。私たちは技術がもたらした驚くべき変化の目撃者なのです。インターネットも、宇宙旅行も、ソーシャルメディアも、以前にはどれも存在しなかったものです。そして今、私たちは技術によって未来や街や世界を変える事ができると信じているのです。そのことに疑いはありません。ですが、それが唯一の可能性だというわけでありませんし、ベストな方法だとは限りません。

森山さんの家での過ごし方を観察された中で、西洋の私たちにとって教訓になるようなことはありますか?

彼がいつも色んな方法で空間を探しているのには、驚きました。場所を変えるのが好きなんです。例えば、読んでいる本のテーマによっても場所を変えています。

1ページ、2ページと読み終わると、次のエピソードやチャプターに最適な場所を決めていくのです。私たちもやるべきですね。家具を動かしたり、配置を変えたり、いつもは行かない部屋のコーナーに行ってみたり。理由はなんでも構いませんが。

1、2年前になりますが、メンドリジオの学生が、彼とフラットメイトたちが、家の中の空間をどのように使っているのか、映画を撮影しました。3人全員の動きを記録し、そのデータから「空間利用」のダイアグラムを作ったのです。そこでわかったのは、使える空間のうち彼らは40%しか使っていないということでした。そこで、彼は家具の配置を変えて、3人がもっと空間を使えるようにしたのです。その実験後にまた、動きを記録したダイアグラムにして見てみると、今度は75%の面積を使っていることがわかりました。つまり、私たちの多くは、先天的に空間という概念を捉えてはいるということです。森山さんのように、空間の探求をしようとすれば、多くのことを学び発見できるのです。

若い建築家は、家庭的空間とはどのようなものかを理解する前提として、私たちに受け継がれている社会文化的なパターンを疑う姿勢を持つべきだと思うのです。私たちは、家というものが、どのように作られ、そこに住み、使われるべきか、ということに対して多くの固定観念を持ってしまっています。特定の空間での特定な機能や振る舞い方を想定してしまっているからです。そんな状況の中で、「そんなパターンなんか全部壊してしまって、自由を手に入れたいのだ。」と言ってしまうには、努力が必要ですし、意識的な決断が必要です。自分の正しいと思うこと、あるいはそうでないと思うことに逆らっていく強さが欲しいですね。子供の頃に戻って、人生の中で今までずっと言われてきたことを忘れる必要があるのです。子供はいつだって、びっくりするようなやり方で物を使いますよね。椅子とか、空間に関するものとか、なんでもです。子供は文化的に規定されたことから完全に自由な存在ですから、色んなものを探し出して、遊びに変えてしまうのです。

どうすれば森山さんのように、センスのある観察者になれるのでしょうか?

私たちには4歳になる息子がいます。ある日、彼に聞いてみたのです。「ベッドルームは好き?ベッドの位置はそれがいいかな?」彼にとって、その時の質問は奇妙なものに感じたと思います。私たちは、彼に生活に最も近い空間について考えてみて欲しかったのです。彼は答えました。「うん。でもなんでそんなこと聞くの?」私たちは伝えました。「変えたいなら変えてもいいのよ。部屋の反対側に置いてみようか?そうしたら、朝、窓から鳥とか雲とか見えるものね。」すると彼は「ああ、そうだね。ナイスアイデアだね。」と言ったので、私たちはベッドの場所を移動したのです。

数日後に、彼は私たちのところにやってきて、ベッドを元の位置に戻したいんだと、言ったのです。理由を尋ねてみると、元の位置からはドアが見えて、そこから私たちが入ってくるのが見えたのだと。そうです。この瞬間、彼は自分のパーソナルスペースがどうやって組織化されていたのかを考え始めたのです。私たちが、部屋に入ってくるのが見えると、心地よく安心するのだと気づいたのです。素晴らしいことでしょう。もし子供に、学校でもこういったこと、例えば部屋のレイアウトを変える練習などが教えられたら、子供たちは空間というものを意識し始めるでしょう。空間体験とは何であるか気づくはずなのです。その子供たちなら、20歳を過ぎ、街に出る頃には、こんな街良くないし、ちゃんと直さないと住めないよ、と言うでしょう。こういったことは、残念ながら過小評価されてしまっているテーマですね。小学校から、子供たちにこういった疑問を投げかけ、空間の物理的な組織化とそれに伴う心理的、そして感情的な作用に関して、集団的に意識を育むことができるとすれば、社会にも大きな変化をもたらすことができるのだと思うのですが。

この点で、森山さんは、子供のような無邪気さを持ち続けている人として、素晴らしい事例だと思います。家庭空間の文化的パターンによって構造化されたり、訓練されたりしていないのです。彼は私たちの求める繊細な観察者で、空間への参加者なのです。彼とともに暮らすことで、私たちが映画を撮っているときに理論化しようとしていることの全てに触れているのだと言えるでしょう。彼の中にすべてがあるのです。

私たちが、彼から学んだのは、彼のささやかな存在感、五感を駆使して瞬間を生きていく強さです。合理的な西洋の成人は、この開放的な状態を忘れがちなのです。私たちの文化では無邪気さと結びついてしまうからでしょう。無邪気さは、社会的制約によってあまりにも多く失われてしまっています。忘れ過ぎないように気をつけないといけませんね。

2021年10月13日

Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine: For a significant part of his life, Moriyama-San worked from home in a liquor shop owned by his mother. When his mother passed away, he decided to demolish her house and the shop to build a new house, in the exact same place. He was up to the idea of putting himself into an experiment and wrote a letter directly to the architect Ryue Nishizawa believing he was the right professional to challenge his hitherto way of life. Moriyama-San and Ila became friends through a common interest in Japanese noise music, that’s how Ila could stay with him in his house for a week during the summer of 2017.

HOW WAS HIS LIFE BEFORE?

The original house, if we understood well from what Ryue Nishizawa told us, didn’t have windows as such, as they were completely covered with shelves, filled with books. It was compact, closed and rather dark. Building a new house for Moriyama-San was in some way building a new way of life for him. He changed radically from a sort of a nerd, living in a dusty and slightly stifling environment, to a wild cat in a little urban forest.

Today, his domestic life is divided between separate living units spread over the small site. Some of them are only one floor, some have stairs that lead to higher levels. Some have some spaces underground as well. The house pushes him to move up and down and between the cubes in the open air, regardless of rain, snow, or wind. He constantly must step outside to go to the kitchen, or bathroom. This fragmented organisation of domestic life constantly provokes unconventional and surprising situations.

What in a more standard house would be considered as a living room, that is to say a central space unifying individual and isolated rooms is assumed by the small central garden. So, it’s the outside which plays this unifying role among smaller units.

BEING THERE, DID YOU FEEL PROTECTED, OR RATHER EXPOSED TO THE CITY?

In the film « Tokyo Ride » we shot with Ryue Nishizawa, he evokes in a particular way how different Japanese and Occidentals behave in regard to the idea of protection or exposure of the self in society. Westerners usually build their identity on the principle of the individual strength. They need to seem powerful and prepared for a social relationship perceived as a conflict. Even if they can behave in very cordial and diplomatic ways, they are constantly, even if unconsciously, envisioning the social interaction as a potential confrontation in which hierarchies of power are at play. On the contrary, Nishizawa presented the Japanese people as « disarmed », in the sense that they are not moved by such a pressure of conflict in the relation to one another. You can strongly feel this in the almost total absence of aggressiveness in Japanese cities. I am not fully sure it can also explain the appeal towards transparency in contemporary Japanese architecture, but it would be interesting to investigate this further.

On this point of protection or exposure in architecture, we have also been really amazed to understand how Japan deals, in general, with thermic insulation. Because of their hot and humid climate, traditionally they have conceived an architecture of porosity - to allow natural ventilation within a building. What is very surprising is that even today this idea of thermic porosity remains. Walls are often thin, fragile even, and when inside, you feel closely connected to the outside in terms of either temperature or sound. So, it means that in winter you get very cold and very hot in summer.

But this is also related to a larger fascination and respect towards nature and its strength in Japanese culture.

IT’S A VERY INTERESTING QUESTION, BECAUSE IT RELATES TO THE CULTURAL RULES DEFINING PRIVACY AND RESPECTING OTHERS.

The question of privacy is essentially a cultural definition which is understood very differently from one country to another. For instance, when we were in Copenhagen shooting a film in Bjarke Ingels’ 8 House, we experienced another variation on this paradoxical idea of « exposed intimacy ». Because of the lack of natural light during winter months in Denmark, there is a high preoccupation with light, people there have big windows with no curtains. In the evening, as a passer-by, you could see everything happening in the house, the most intimate family gatherings, people in their bedrooms, etc. The Moriyama House is very similar in this aspect. It is also built with huge openings, which merge the inside and the outside. It works well, because both in Japan and Denmark the culture is based on a high level of mutual respect. You see people passing by, neighbours on bikes, in cars, children running, old people walking, stopping, and so on. It’s an all-day sort of continuous flow but no one is supposed to peep in. The only ones who actually do, even in rather rude ways, are foreigners - as Moriyama San recounted to us. To avoid this, he has placed a board on the street, written in English, asking architecture tourists if they could kindly avoid stepping in the private area of the garden.

Despite the transparency of the large openings on the street side, the intention of Nishizawa was to slightly separate the owner from the city and create, thanks to the central small garden, a peaceful protected place and it has been achieved, but just in a very balanced, idiosyncratic way. You are neither cut off nor completely exposed. You always have a choice, and it gives a very pleasant feeling.

IN EUROPE, WHEN WE THINK ABOUT A CONNECTION OR HARMONY WITH NATURE, USUALLY WE IMAGINE BUILDINGS MADE FROM NATURAL MATERIALS. MORIYAMA HOUSE IS A SERIES OF ABSTRACT WHITE BOXES. WHAT EFFECT DOES THIS HAVE?

In this case architecture is a device to connect you with nature, but not necessarily a part of nature itself. The materials are not meant to have any rhetoric meaning or tell explicitly a story of belonging linguistically more to the garden rather than to the street. The house is minimal and left without any symbol of luxury, in order not to distract you from its main purpose. In terms of furniture and facilities, it offers the minimum Moriyama-San needs to live. For instance, the kitchen is used mainly to put beers in the fridge - but not to cook large meals for many guests or even himself. The house does not have what we would call a bedroom either which in truth, is extremely radical as sleeping on the floor was quite an experience.

In terms of our way of understanding a house, this house is a series of cubes, little rooms and angles that are dedicated to enjoying space and the present moment. It is not a technical device to answer all our needs or a manifestation of an ideology. It all works in such a simple and minimal way. Beyond its domestic functions, the way Moriyama-San lives this house is a place to experience the emotions produced by the subtle interaction between the space, the garden and the movement of people passing by.

WHY IS A HOUSE AN INTERESTING TOPIC FOR A FILM?

We figured out very early that most films on architecture were basically descriptive, focusing on the buildings’ aesthetic features, the materials, the structure, the various innovative features, etc.

In a word, an architecture film very often serves the specific role of being a promotional and communication tool for architects, and that induces necessarily a certain aesthetic with a sense of seduction in the way you make a film. In opposition to that, we have been looking to distort the relation of subordination between film and architecture, in order to find a real critical freedom which could open up a debate about how architecture is being represented. Film allows us to question the relationship we develop as human beings with our surrounding space. That’s why our main effort has been the one of placing people at the forefront of architecture’s representation to question architecture, its role and impact, from a more anthropological point of view. This led us to choose the house as the most interesting narrative device, because there is no other space we fill with more emotion, memories, and intimacy. The house is as much a spatial reality as a mental territory. This psychological richness made us understand that it was an endless reservoir of personal and moving stories.

IS THEN „MORIYAMA-SAN” A FILM ABOUT THE HOUSE OR ABOUT THE PERSON?

We’ve always tried to avoid filming the figure of the owner or the architect because they usually are excessively involved with the project, in an emotional way. They are acting, like in a theatre, and are rarely able to have sufficient distance to talk about the building in a natural and un-staged way.

Moriyama-San was an exception from the rule. He is not representing what we would call the typical pride of an owner. An occidental individual would be much more into social representation. In contrast, Moriyama-San was incredibly natural, and detached, breaking all cliches about the owners of buildings that are recognised as architectural achievements.

What’s marvellous about him is that he seems essentially interested in his house for his pure personal enjoyment, that’s quite unique.

The idea was to talk about the space through the way it is being lived and experienced. So very much about the physical and psychological interaction with space. Rather than talking about the qualities of a space in an abstract way, we like to explore those qualities through the sensorial and emotional relationship an individual will create with the space he inhabits. And Moriyama-San is exceptional for this. It was a revelation for us. It was probably the first time we were so closely and intimately immersed within a sensibility very new for us, so subtle, so refined in its attention to micro atmospheric phenomena and so many aspects we rarely pay attention to in our busy urban lives. He is certainly very Japanese in his sensibility, but this was our first close connection with Japanese culture, so we were really amazed how receptive they are in sensorial terms. In many moments of the film, you can understand that Mr Moriyama moves through the house, chooses where to sit, to lie down or to stay depending on the qualities of light, sound, wind, temperature, etc. His way through the building is led by this sensorial intuition rather than by functional necessities and that’s just marvellous. It was such an enlightening encounter for us. We learned so much from his ultra-sensitivity. It reinforced our conviction that the best way of recounting a space is through its fully immersive and intimate experience and this is precisely what cinema allows to do.

WHAT EXPERIENCES WERE YOU EXPOSED TO IN THE MORIYAMA HOUSE?

The scale of the house was very surprising. All these spaces are very small. You must physically adapt to enter them and move in a very precise and delicate way.

It calls for a sort of physical dialog with space like a precise choreography, otherwise you may bump into everything, knocking down objects and furniture upon each move. So, you must be extremely careful of how you move and where you step, because the house is also quite dangerous, there are no fences or railings. There are holes and large openings, very small ladder, etc. So it’s a sort of physical playground requiring to be in a constant state of alert. The house proposes a kind of sensory kaleidoscope where each place offers different conditions and requires different types of awareness.

The first feeling, as occidental adults, was that our body was deeply unadapted as we are more accustomed to large spaces. We are not used to master our movements in such a precise way, to fit to the small dimensions of a Japanese house. In the West, we also take it for granted that the architect cares about our safety, so we do not really pay attention. We really felt physically massive and a bit rough in the way we behave, so being there was undergoing a sort of re-education of body language. From childhood, Japanese are trained to adapt to the constraints of small scale and are thus much more measured and in control of their movements.

SO, YOU UNDERSTAND THE TRUTH OF A SPACE BY WATCHING HOW SOMEONE EXISTS IN IT?

Rather than « truth » I would say more its inner qualities. This intuition also became the direction we gave to our teaching at the AA, where we led a master studio entitled « Laboratory for Sensitive Observers ». This course intended to introduce students to the « art of seeing », in developing tools and methods to increase their skills of observation. The aim, on a larger scale, was to develop their sensitivity and understanding of the cultural features legible in our social behaviours, but also political and economic forces that are at play in our urban life.

Our intent was to raise awareness on how important the quality of observation and the sharpness of a site analysis, in the complexity of its socio-cultural and historical components, is what will make the students’ future proposals as young architects more accurate and relevant, with a strong human sensitivity.

DO YOU THINK THE CAPACITY OF OBSERVATION IS IN DANGER NOWADAYS?

We seem to live in an era of acceleration. There is great time pressure on the need to produce, to be very efficient and go straight to the point. There is perhaps, less value in the idea of taking stock, thinking what-is-what, and spending time understanding something for ourselves. We also saw this in our students, who are very motivated to produce forms or to reach a goal but less interested in, or unable to, linger on something, to wander. They try to quickly achieve something, whatever it is. And this acceleration goes together with a reduced attention and availability to what surrounds you.

We also live in an era of total fascination with technology, which is sometimes crazy. If you think about the last 20 or 30 years, we are witnesses to an incredible change brought about by technology. We have the internet, space tourists, social media, none of which existed before. Now we believe we can change the future, the city, and the world with technology. This is certainly true, but perhaps it’s not the only possible and not necessarily the best way.

WHAT IS YOUR OBSERVATION ON THE WAY MORIYAMA-SAN LIVES IN HIS HOUSE THAT COULD BE A LESSON FOR US IN THE WEST?

We were amazed to see that he continuously explores space in different ways. He loves changing place, even for instance, according to the subject of the book he is reading. He reads one or two pages and after that, he decides where to go to best fit the next episode or chapter. It’s something that we should also do in our own spaces - move furniture, change the arrangements, go to the corner that we never go to, regardless of reason.

One or two years ago, a student from Mendrisio made a film about how he and his flat mates used the space inside their house. He recorded the movement of everyone, 3 people, and used the data to make a ‘space use’ diagram. It showed that out of all the available space, they were using only 40 percent. He decided to change the layout of furniture to push the 3 people living there to use more space. After the experiment, he recorded their movements again, and his new diagrams showed that they used 75 percent of the area. It shows that most of us have in mind a conception of space that has been prepared for us. But if you try to explore, as Moriyama-San does, you can learn and discover a lot.

We believe young architects should be more prepared to put into question what we inherit in terms of socio-cultural patterns in the way we understand the domestic space. We have so many stereotypes of how a house should be organised, lived, and inhabited, with very specific functions and ways of behaving in certain spaces. It requires an effort, a conscious decision to say: “We want to disrupt all those patterns and introduce a certain degree of freedom”. It requires strength to go against what you consider right or not. You need to go back in time to when you were a child and forget what you have been told your whole life. A child always uses things in the most surprising ways, whether it is a chair or anything else related to space. A child will try to explore, to transform things into something to play with as he or she is still totally free from any cultural conditioning.

HOW CAN WE BE MORE LIKE MORIYAMA-SAN – HOW CAN WE BE MORE SENSEFUL OBSERVERS?

We have a son; he is just four years old. One day we asked him: “Do you like your bedroom? Do you like the position of the bed?”. For him, at that moment, it sounded like a very strange question. We provoked him to think about the space of his most intimate daily life. He said: “yeah, but why do you ask?”, we said, “We could change it, if you want. We could put the bed at the other end of the room, in the other direction so that you could look out of the window in the morning, see the birds or the moving clouds”, he said, “oh yes, that is a good idea”. We moved his bed.

Some days later, he came and told us that he would like to put the bed back like it had been before. We asked why and he answered, that before, he could see the door from where we entered. So, what happened in this very moment is that he started to think about the meaning of how his personal space was organised. He realised that he felt more secure, more comfortable when he could see his parents coming into the room. This is incredible. If you were to teach this to kids at school, with exercises of this kind, for instance changing the layout of their bedroom, they would start to be conscious of space – to be aware of what a spatial experience is. One day they would go outside into the city, when they are twenty years old or more and say that they cannot live in the city because it is not good, that it must be fixed. I think this is a topic that unfortunately is underestimated. If we could introduce from primary school that kind of questioning, to develop collective awareness regarding the physical organisation of space and its psychological and emotional consequences, it could make a big difference.

In this respect, Moriyama-San is an incredible example of a person who has maintained what we would call the innocence of a child. He is not trained or structured by any cultural patterns of domesticity. He is the sensitive observer and participant in space that we search for. We can say that living with him, we were exposed to all the things that we try to theorise about during the making of our films. We can find them all in him.

What we learned from him is his subtle degree of presence, an intensity in the way he lives the present moment through all his senses. As rational occidental adults we tend to forget this state of openness, which in our culture would be associated with innocence – too much is lost through our own social conditioning. But we should be careful not to forget too much.

13.10.2021

伊拉-贝卡和路易丝-勒莫奈: 在他生命中的大部分时间里,森山先生都在家里为他母亲开的酒 类商店工作。当母亲去世后,他决定拆除她的旧宅和商店,在原地建造一栋新的住宅。他想把自己投入到一种实验中,并直接给建筑师西泽立卫写了一封信,相信他正是挑战自己迄今为止的生活方式的专业人士。森山先生和伊拉通过对日本噪音音乐的共同兴趣成为了朋友,这就是为什么在2017年夏天,伊拉能够和森山先生一起在他的住宅里待了一周。

他以前的生活是怎样的?

原来的住宅,如果我们很好地理解了西泽立卫所说的,没有现在这样的窗户,因为它们完全被 架子覆盖住了,填满了书。它很紧凑,封闭,而且相当黑暗。为森山先生建造一座新房子,在某种程度上就是为他建造一种新的生活方式。他从一个生活在铺满灰尘、略显窒息的环境中的书呆子,彻底转变为都市小森林中的一只野猫。

今天,他的居家生活被分布在小基地上的独立生活单元所分割。有些只有一层,有些则有楼梯通向更高的楼层,有些还有一些地下空间。这所住宅促使他在露天的立方体之间上下移动,不论风霜雨雪。他必须不断地走到室外去,去厨房或者浴室。这种碎片化组织的居家生活不断引发非传统的和令人惊讶的情况。

在一个更标准的住宅中,客厅会被认为是一个中央空间,将各个孤立的房间统一起来,而这座住宅中,小小的中心花园却承担了这个任务。所以,是户外空间在这些小单元中扮演起了这种统一的角色。

在那里,你是否感到受到保护,或者说暴露在城市中?

在我们与西泽立卫拍摄的电影《东京之旅(Tokyo Ride)》中,他以一种特殊的方式唤起了,日本人和西方人在社会中自我保护或暴露的想法上会表现得多么不同。西方人通常在个人力量的原则上建立起他们的身份。他们需要显得强大,并为被视作冲突的社会关系做好准备。 即使他们能以非常亲切和变通的方式行事,他们也不断地,甚至是无意识地,将社会互动设想 为潜在的对抗,其中权力的等级制度在发挥作用。相反,西泽将日本人描述为"缴械式的",即 在相互关系中,对于这种冲突的压力,他们不为所动。你可以从侵略性几乎完全缺失的日本城市中,强烈地感受到这一点。我不完全确定这也能解释当代日本建筑中对透明性的诉求,但进一步研究这个问题会很有趣。

关于建筑中的保护或暴露这一点,我们也非常惊讶地了解到,一般来说,日本是如何处理隔热问题的。由于他们炎热潮湿的气候,传统上他们构思了一种充满孔隙的建筑——允许建筑内部自然通风。非常令人惊讶的是,即使在今天,这种导热气孔的想法仍然存在。墙壁通常很薄,甚至很脆弱,在里面,你会感觉到在温度或声音层面上与外界紧密相连。因此,这意味着在冬天你会感到非常寒冷,而在夏天则很热。

但这也与日本文化中更宏大的,对自然及其力量的迷恋与尊重有关。

这是一个非常有趣的问题,因为它关乎于定义隐私和尊重他人的文化规则。

隐私问题本质上是一个文化定义,在不同的国家有非常不同的理解。例如,当我们在哥本哈根BIG事务所的 8 House拍摄电影时,我们经历了关于 "暴露的亲密性 "这种矛盾想法的另一种情形。由于丹麦在冬季缺乏自然光,人们对光照的关注度很高,那里有着不挂窗帘的大窗户。 在晚上,作为一个路人,你可以看到房子里发生的一切,最亲密的家庭聚会,人们在自己的卧室,等等。森山居在这方面非常相似。它也是用巨大的开口建造的,将内部和外部融合在一起。这行之有效,因为日本和丹麦的文化都是基于高度的相互尊重。你看到路过的人、骑自行车的邻居、开车的人、奔跑的孩子、走路的老人、停下来的人,等等。这是一种全天的连续人流,但没有人会去偷看。唯一真正这样做的,甚至以相当粗鲁方式的,是外国人——正如森山先生向我们讲述的那样。为了避免这种情况,他在街上放置了一块用英语书写的板子,询问建筑业游客是否可以善意地避免踏入花园的私人区域。

尽管街道一侧的大开口是非常通透的,但西泽的意图是将业主与城市稍适隔开,并通过中央的花园创造一个宁静的保护地,这已经实现了,而仅仅以一种非常平衡、特异的方式。你既不被 隔绝也不完全暴露。你总是有所选择,它给人一种非常愉悦的感觉。

在欧洲,当我们考虑到与自然的联系或协调时,通常我们会想象由自然材料制成的建筑。森山住宅是一系列抽象的白盒子。这有什么样的效果?

在这种情况下,建筑是连接你和自然的一个装置,但不一定是自然本身的一部分。这些材料并不意味着有任何修辞上的意义,或明确地讲述一个在语言上更属于园子而不是街道的故事。为了不分散你对其主要意图的注意力,住宅是极简的,并且没有任何豪华的标志。在家具和设施方面,它提供了森山先生生活所需的最低限度。例如,厨房主要用于在冰箱里放啤酒——但不用于为许多客人甚至自己做大餐。这所住宅也没有我们所说的卧室,这实际上是非常激进的, 因为睡在地板上确实是一种不同寻常的经历。

就我们理解住宅的方式而言,这个住宅,正如你所说的,是一系列的立方体、小房间和角落,专门用来享受空间和当下。它不是一座满足我们所有需求的技术装置,也不是一种意识形态的体现。它全都由这样一种简单和的最低限度的方式运作。除了居家功能,森山先生在这所住宅 中的生活方式,是将其作为体验空间、花园和路人活动之间微妙互动所产生的情绪的场所。

为什么住宅是电影的一个有趣的主题?

我们很早就发现,大多数关于建筑的电影基本上都是描述性的,关注建筑的美学特征、材料、结构、各种创新特征等等。

一句话,建筑电影的特定角色往往是作为建筑师宣传和交流的工具,而这必然会推行某种美学,使你在拍摄电影时有一种引诱的感觉。与此相反,我们一直在探寻如何扭转电影和建筑之间的从属关系,以便找到一种真正的批判自由,从而能够开启一场建筑表现方式的辩论。电影使我们能够质疑我们作为人类与周围空间的关系。这就是为什么我们致力于把人放在建筑表现的最前线,从一个更人类学的角度质疑建筑、它的作用和影响。这导致我们选择住宅作为最有意思的叙事装置,因为没有其他空间能让我们充满更多的情感、记忆和亲密性。住宅既是空间现实,也是精神领域。这种心理上的丰富性使我们明白,它是一个无尽的个人的动人的故事宝库。

那么《森山先生》是一部关于住宅还是关于人的电影?

我们一直试图避免拍摄业主或建筑师的形象,因为他们通常以一种情绪化的方式过度地参与项目。他们在演戏,就像在剧院里一样,很少能够有足够的距离,以一种自然和非舞台的方式谈论建筑。

森山先生是这个规则的一个例外。他并不代表我们所说的典型的自豪感的业主。一个西方人会更喜欢成为社会性的表象。相比之下,森山先生是非常自然和超然的,他打破了所谓具有成就的建筑物的业主的所有陈规。

他的奇妙之处在于,他似乎热衷于自己的住宅,纯粹是为了个人的乐趣,这一点很独特。

我们的想法是通过居住和体验的方式来谈论这个空间。所以非常注重与空间物理和心理层面的互动。与其以抽象的方式谈论一个空间的品质,我们喜欢通过个人与其栖居地所产生的感官与情感的关系来探索这些品质。而森山先生在这方面是出类拔萃的。这对我们来说是一种启示。这可能是我们第一次如此密切又亲近地沉浸于对我们来说很新鲜的感觉中,如此精妙、细致地关注微小的大气现象和我们在繁忙的城市生活中很少关注的方方面面。他的感觉当然非常日本化,而这是我们与日本文化的第一次亲密接触,我们真的很惊讶于他们感官上的接受能力。在影片的许多时刻,你可以理解森山先生在住宅中的移动,根据光线、声音、风、温度之类的品质来选择坐、躺或待在哪里。他如何穿行于建筑是由这种感官上的直觉而不是功能上的需要来 引导的,这实在是太奇妙了。这对我们来说是一次充满启发性的邂逅。我们从他极致的敏感性中学到了很多。它加强了我们的信念,即叙述一个空间的最佳方式是通过完全沉浸式的密切体验,而这正是电影艺术所能做到的。

你在森山邸中触及到了什么样的体验呢?

这所住宅的尺度令人很惊讶。所有的空间都非常小。你必须在身体上适应步入其中,并以一种非常准确和精巧的方式移动。

这会唤起一种空间和身体上的对话,就像一支精确的编舞,否则你随时可能会撞到,每次移动都会碰倒物件和家具。你务必十分小心自己的移动方式和脚步,因为住宅也相当危险,没有围栏或扶手。这里有洞和大的开口,非常小的梯子等。所以它像是一种物理层面上的游乐场,需要时刻保持警惕。这所住宅提供了一种感官万花筒,每个场所给予了不同的条件,并要求着不同类型的意识。

作为西方成年人,我们的第一个感觉是身体上的不适应,因为我们更熟习于大空间,而不习惯以如此精确的方式控制我们的行动,以适应日本住宅的小尺度。在西方,我们也认为建筑师理应照顾我们的安全,因此我们不会很小心。我们确实感到自己的身体庞大,行为方式有点粗糙,所以在那里经历了一种身体语言的再教育。从孩童起,日本人就培养了对小尺度制约的适 应性,因此对自己的动作更有分寸和控制力。

所以,你通过观察人在其中的存在方式来理解一个空间的真相?

与其说是"真相",不如说是它的内在品质。这种直觉也成为我们在AA的教学方向,我们在那里指导了一个名为"敏感观察者的实验室"的研究生工作室。这个课程旨在向学生介绍 "观察的艺术",开发工具和方法来提高他们的观察技能。课程的目的,以更大的范围来说,在于开发他们的敏感性和理解力,针对于我们社会行为中可识别的文化特征,以及在我们城市生活中发挥作用的政治和经济力量。

我们的意图是提高对于观察的质量和场地分析的敏锐的重要性的认识,在社会文化和历史成分的复杂性中。这将使学生未来作为年轻建筑师的建议更加精准和贴切,具有强烈的人文敏感性。

你认为现今,观察能力式微吗?

我们似乎生活在一个加速的时代。对生产需求有很大的时间压力,要非常高效,直奔主题。也许,总结、思考什么是什么、花时间理解自己的想法,这些事情价值更小。我们也在我们的学生身上看到了这一点,他们非常积极地制作表格或达成一个目标,但对事情本身不太感兴趣, 或无法在上面流连,徘徊。他们试图快速的实现一些东西,无论它是什么。而这种加速伴随着对你周边事物的关注与获得的降低。

我们还生活在一个对技术完全着迷的时代,这有时是疯狂的。如果你想想过去的20或30年,我们见证了技术带来的不可思议的变化。我们有了互联网、太空旅行、社交媒体,这些都是以前不存在的。现在我们相信我们可以用技术改变未来,改变城市,改变世界。这是当然可行的,但这也许不是唯一可能的,也不一定是最好的方式。

你对森山先生在家里的生活方式有什么看法,可以作为我们西方人的借鉴?

我们惊讶地看到,他不断以不同的方式探索空间。他喜欢改变地点,甚至比如说,根据他正在阅读的书的主题。

他读了一两页,之后,他决定去哪里最适合下一段或下一章。这是我们在自己的空间里也应该做的事情——移动家具,改变计划,去我们从未去过的角落,不管是什么原因。

一两年前,一位来自门德里西奥的学生拍了一部电影,讲述他和他的室友们如何使用住宅里的空间。他记录了每个人的行动,3个人,并使用这些数据制作了一个"空间使用"图。它显示,在所有可用的空间中,他们只使用了40%。他决定改变家具的布局,促使住在那里的3个人使用更多的空间。实验结束后,他再次记录了他们的行动,他新的分析图显示他们使用了75%的面积。这表明我们大多数人心中都有一个已经准备好的空间概念。但是,如果你像森山先生那样努力探索,你可以学习和发现很多东西。

我们相信年轻建筑师应当准备好去质疑我们在社会文化模式方面所继承的对居家空间的理解方式。我们有很多关于住宅应该如何组织、生活和居住的刻板印象,裹挟着非常具体的功能和在某些空间的行为方式。这需要一种努力,一种有意识的决断,说:"我们想瓦解所有这些模式,并引入一定程度的自由"。它需要力量来反对你认为正确或不正确的东西。你需要回到你还是个孩子的时候,忘记你终生中被告知的事情。一个孩子总是以最令人惊讶的方式使用物品,无论是椅子还是与空间有关的其他东西。孩子会尝试探索,把事物变成可以摆弄的样子,因为他或她还完全不受任何文化制约。

我们怎样才能更像森山先生——我们怎样才能成为更有意义的观察者?

我们有一个儿子,他才四岁。有一天,我们问他。"你喜欢你的卧室吗?你喜欢床的位置吗? "。对他来说,在那一刻,这听起来是一个非常奇怪的问题。我们激发他思考他日常最亲密的生活空间。他说:“是的,但你为什么这么问?”我们说:“如果你想,我们可以改变它。我们可以把床放在房间的另一端,换一个方向,这样早上你就可以从窗户向外望,看到鸟儿或移动的云彩。”他说:“哦对,这是一个好主意。”我们移动了他的床。

几天后,他来告诉我们,他想把床放回以前的样子。我们问他为什么,他回答说,以前,他可 以从我们进来的地方看到门。因此,在这一时刻发生的事情是,他开始思考他的个人空间组织方式的意义。他意识到,当他能看到父母进入房间时,他感到更安全、更舒适。这真是不可思议。如果你在学校教孩子们这些,通过这种练习,例如改变他们卧室的布局,他们会开始意识到空间——意识到什么是空间体验。有一天,当他们20岁或更大的时候,他们会走到室外进入城市,说他们不能住在城市里,因为它不好,它必须被修复。我想这是一个不幸被低估的话题。如果我们能从小学开始引入这样的问题,以发展对于空间的物理组织及其心理和情感后果的集体意识,这可能会带来很大的改变。

在这方面,森山先生是一个令人难以置信的例子,他一直保持着我们称之为孩童的纯真。他没有受到任何家庭文化模式的规训或结构化。他是我们所寻找的敏感的观察者和空间的参与者。可以说,与他一起生活,我们接触到了所有我们在制作电影时试图理论化的东西。我们可以在他身上找到所有这些内容。

我们从他身上学到的是他微妙的存在感,强烈的通过所有感官活在当下。作为理性的西方成年人,我们倾向于忘记这种开放的状态,在我们的文化中,这种状态会与纯真联系在一起——丢失了太多由于我们自己的社会环境。但我们应当注意,不要过多的遗忘。

2021年10月13日

イラ・ベカ&ルイーズ・ルモワンヌ: 森山さんは、人生の大半を母親の経営する酒屋で働いていました。その母親が亡くなった時、家と酒屋を取り壊して、まったく同じ場所に新しく家を建てることにしたのです。彼は自分を実験台とする思いで、建築家、西沢立衛に直接手紙を出しました。彼こそが、今と変わらない生活に、新たなチャレンジを与えてくれるプロフェッショナルとして適任だと思ったのです。イラは、日本のノイズミュージックが好きだという共通点から森山さんと仲良くなり、2017年の夏に1週間ほど、彼の家に滞在させてもらったんです。

森山さんの以前の生活はどういうものだったのでしょうか?

元の家は、西沢さんが教えてくれたことから想像するに、部屋は、本で埋め尽くされた棚で覆われていて、窓がなかったようです。コンパクトで閉鎖的で、どちらかというと陰気な生活でした。森山さんにとって家を建てるとは、ある意味、彼の生き方を新しくすることでもあったのです。オタク的で、埃っぽく、窮屈な生活から、都会の小さな森の中で生活する野良猫のように彼の生活は激変したのです。

現在の彼の生活空間は、小さな敷地に散らばったそれぞれの住戸に分かれています。一層だけのものもありますし、上の階へと登れるものもあります。地下にあるものもありますね。雨の日も、雪の日も、風の強い日も、登ったり降りたりしながら、屋外にあるそれぞれのキューブの間を移動しなくてはいけないのです。キッチンやバスルームに行くには、外に出ないといけないですしね。このように生活空間が断片化された構成は、型破りで驚くような状況を提起するものです。

一般的な住宅においてリビングとして考えられる空間、つまり個々の独立した部屋をまとめる中心的な空間は、中央の小さな庭が担っているのです。そう、小さなユニットをまとめあげているのは外部空間だということです。

森山邸にいるときには、守られているような感じはありましたか?それとも都市に対して晒されているような感じがありましたか?

西沢さんと撮影した映画『Tokyo Ride』で彼は、社会の中で、自己を保護する、あるいは露出するという概念に対しての日本人と西洋人との行動の違いを、ユニークな視点から提起しています。西洋人は、たいてい個人の強さに基づいてアイデンティティを築いていくので、力強く見えることは、必要なことですし、対立的な社会的関係にも備えておく必要があるのです。非常に好意的に、そして外交的に振る舞うことができるのですが、そんな際にも常に、無意識にも、権力の力関係が作用している潜在的な対立を社会的な相互作用としてイメージしてしまうのです。それに対して、西沢は、日本人は「武装解除された」状態なのだと説明します。相手との相互作用によって生まれる対立的圧力に動機付けられた存在ではないということです。それは日本の都市に攻撃性がほとんどないことからも強く感じられることでしょう。日本の現代建築に見られる透明性へのアピールもそれが理由なのかどうかは、わからないのですが、関係性をもっと調べるのは面白いかもしれませんね。

建築における保護と露出という点では、日本での一般的な断熱の扱いには、とても驚きましたよ。日本は、高温多湿な気候なので、伝統的に建築は多孔性のものだと捉えられているのです。そうすると建物内での自然換気も可能ですから。さらに驚きなのは、この熱に対する多孔性という考えが今日においてもまだ残っているということです。壁は、たいてい薄くて脆く、室内にいても温度や音という点では、外と近く繋がっているように感じられるのです。冬はとても寒く、夏はとても暑いということです。

しかし、このことは、自然への興味や敬意と関係していることだと思いますし、それが日本文化の強みでもあると思います。

これは、とても面白い問題ですね。プライバシーや他者へのリスペクトは、それを定義づける文化的なルールに関連することですよね。

プライバシーの問題は、基本的に文化的な定義によるものですし、国によって捉え方は大きく異なります。例えば、コペンハーゲンでビャルケ・インゲルスの『8 House』の映画を撮影していたとき「晒された親密さ」という逆説的な考え方を経験したのです。デンマークでは冬の間、自然光が少ないこともあり、光への関心が高く、大きな窓にもカーテンをしない人が多いのです。だから夕方になると、通りすがりの人が、家の中で起きていることの全て、例えば家族の親密な集まり、寝室での様子など、を見ることができてしまうのです。この点では森山邸はとても似ていますね。大きな開口部があって、それによって内部と外部が混ざり合っている。日本にもデンマークにも、互いを尊重する文化があるからうまくいくのでしょう。通り過ぎる人、自転車や車に乗っている近所の人、走っている子供、歩いたり、立ち止まったりしているお年寄りなどを、絶え間なく流れるように1日中、見ることができるのです。ただし、覗き見をしてはいけないことになっているのです。実際に、覗き見してくるのは、外国人だけだと森山さんは話をしてくれました。中にはかなり失礼な人もいるみたいですが。それを避けるためにも、道に英語で書かれたボードを立て掛けて、観光客には、庭のプライベートエリアに足を踏み入れないようにお願いしているのです。

道路側への大きな開口部は、透明性を作り出しているのですが、西沢さんの意図は、住人を都市から少し切り離し、中央の小さな庭を利用しながら、平和で守られた場所を作り出すことにあったのです。それは、よくバランスのとれた奇妙な方法で達成されています。切り離してしまうのではなく、また完全に晒された状態でもなく。常にどちらにも選択肢がある状態で、それがとても心地よいのです。

ヨーロッパでは、自然との繋がりや調和を考えるときに、たいてい自然素材を使った建物を想像してしまうのですが、森山邸は抽象的な白いボックスの集合体ですよね。これにはどのような効果があるのでしょうか?

この場合、建築は自然とつながるための装置であって、必ずしも自然そのものの一部ではないということです。素材はレトリカルな意味を持っていませんし、言語的にも、家は道路側より庭の方に属しているのだ、とはっきり語っているものでもないのです。この住宅は、ミニマルで贅沢さの象徴などありません。主な目的から気が散らないようにしているのです。家具や設備に関して言えば、森山さんが生活する上での最低限のものは揃っています。例えば、キッチンは主にビールを冷蔵庫に入れるためだけに使われるものであっても、大勢のお客さん、あるいは彼自身のためにたくさんの食事を作るためのものではないのです。私たちが寝室と呼ぶようなものもありません。いや本当に、床に寝るのはとっても過激な体験でしたよ。

私たちの捉え方は、あなたの言う通り、この家は、ボックスの集合体なのです。小さな部屋、そして空間と今この瞬間を楽しむという考えです。あらゆるニーズに応えるような技術的な装置でもないし、イデオロギーの表明でもないのです。シンプルでミニマルな方法によって、全てうまく機能しています。住居としての機能を超えて、森山さんの暮らすこの家は、空間、庭、そして通り過ぎる人々の動きから生じる繊細な相互作用によって生まれる感動が、体験できる場所なのです。

映画にとって、なぜ家が興味深いテーマなのでしょうか?

建築に関する映画のほとんどは基本的に、建物の美的特徴や素材、構造、色々な革新的な機能などに焦点を当てた説明的なものであることに、私たちは早い段階で気づいていたのです。

一言で言えば、建築映画は、建築家のプロモーションやコミュニケーションツールとしての役割を担っている事が多く、映画の作り方は、必然的にある種の美学が誘発されてしまうのです。そのことに対抗して、私たちは、映画と建築の間の従属関係を歪めることで、建築がどのように表現され得るのか、という議論を展開する真の自由を見出そうとしてきたのです。映画は、私たちが人間として周囲の空間とどのような関係を築いているのかを問いかけてくれるのです。そういったことから、私たちの主な取り組みは、建築的表現の最前線に人間を配置し、建築の役割や影響をもっと人間学的な視点から問いかけることとなったのです。だから私たちは家を選ぶのでしょう。感情や記憶、そして親密さで満たされたような空間は、家以外には存在しません。家が最も面白くナラティブな装置なのです。家は空間としての現実でありながら、精神的な領域でもあります。この心理的な豊かさによって、家は、個人的で感動的な物語の無限の貯蔵庫であるということを理解するのです。

では映画『Moriyama-San』は、家についての映画なのでしょうか?それとも人についての映画なのでしょうか?

私たちは、所有者や建築家は、プロジェクトに関わりすぎていて感情的になっているので、いつも撮影しないようにしてきたのです。彼らは劇場で演技しているみたいになってしまいますし、自然に、演出的でなく建物について話せるほど十分な距離感を保てるケースはほとんどありません。

森山さんは例外でした。彼は、いわゆる典型的な所有者としてのプライドを見せつけたりはしないからです。西洋的な個人であれば、もっと社会的な見栄を張ってしまうのですが。逆に、彼はとても自然で、無頓着なのです。建築として認められた建物の所有者としては、常識を逸脱した無頓着さです。

彼が素晴らしいのは、純粋で個人的な楽しみのために、自分の家を面白がっているように見えることですね。すごくユニークなことですよ。

その空間での生活や経験を通して、その空間について話そうとしているのですが、それはつまり空間との物理的、心理的な相互作用が重要だということです。抽象的に空間の質を語るのではなく、そこに住む人が空間とともに作り出す、知覚的で感情的な関係性から、その特質を探求していきたいのです。森山さんはその点では群を抜いて特別な存在です。私たちは天啓を得たのです。微小な気温の変化や、忙しい都市生活の中ではほとんど気にかけないような事にも気づけるような、とても繊細で洗練された感性に、これほどまでに密接にそして親密に触れた経験は、ほとんど初めてのことでした。とても新鮮なものでした。彼の感性は確かにとても日本的なものだと言えるのですが、初めての日本文化との関わりでしたので、日本人の感性の受容性にはとても驚きました。森山さんが家中を動き回っているのは、映画のあらゆるシーンで見ることができると思います。光や音や風、それに温度の質などに合わせて、座ったり、寝転んだり、留まったりする場所を選んでいるのです。機能的な必要性からというより、知覚的な直感に導かれるようにして、建物の中を移動していくのです。単純にすごいでしょう。私たちにとってはとても啓発的な出会いでしたし、彼の超高感度な感性からはたくさんのことを学びました。空間を物語るための最良の方法は、空間への完全な没入とそこでの親密な体験を得ることであるという私たちの確信はより強いものになりました。そしてそれこそが、まさしく映画が可能にしてくれることなのです。

森山邸ではどんな体験を得られましたか?

家のスケールにはとても驚きました。あらゆる空間がとても小さいのです。中に入るには身体を調整しなくてはいけないですし、動くときは正確に慎重に動かなくてはいけません。正確なコレオグラフィーのように空間との物理的な対話が求められます。そうしないと、いろんなものに当たってしまいますし、動く度に家具やオブジェを倒してしまいます。だから、動くときや歩き方には細心の注意が必要です。家もかなり危険ですよ。フェンスや手すりもないですから。穴や大きな開口部、それにとても小さな梯子なんかはあるのですが。常に警戒が必要なフィジカルなプレイグラウンドみたいなものでしょうか。場所によって状況が異なっていますし、その都度、異なる意識が必要です。この家は、感覚の万華鏡のようなものですね。

西洋の成人として初めに感じたことは、身体があまりここに適応できていないということです。広い空間の方が慣れていますから。それに日本の家の小さな寸法に合わせられるほど、正確な身体の動きをマスターできていないのです。西洋では建築家が安全に気を配ってくれている事は当たり前ですから、こういったことに注意を払っていなかったのです。私たちの身のこなし方は、物理的にもがっしりしていて、荒々しいのだと感じました。そこにいると私たちの身体的言語が再教育されているように感じるのです。小さい頃から日本人は、スケールの制約に適応するように訓練されていて、自分の動きをもっと慎重にコントロールできるのでしょう。

人がどのようにその空間に存在しているのかを観察することで、その空間の真実を理解できると言うことでしょうか。

「真実」と言うよりは、「内実」という感じでしょうか。この私たちの直感は、AAスクールでの指導での方針にもなっています。修士学生のスタジオを持っていたのですが、タイトルを「感覚的観察者のラボラトリー」としたのです。このコースでは、観察力を高めるための道具や方法を発展させ「見る技術」を紹介していくことを目的としていました。より大きなスケールでは、私たちの社会的行動から読み取れる文化的特徴だけでなく、都市生活に作用している政治的、経済的な力への理解と感度を高めることを目的としています。

社会文化的、そして歴史的要素が複雑化する中で、質の高い観察力や、敷地へのシャープな分析力がいかに重要なことであるか気づいてもらう事を意図していました。これらが、若い建築家としての将来の提案を、人間的で力強い感受性とともに、より正確な、そして適切なものにしてくれるのだと思っています。

現代において、観察力が弱まってしまっているとお考えですか?

私たちは、加速的な時代に生きているようですね。生産性や効率性、そして目的へと直行することへの大きな圧力があるわけですが、何かを理解するために時間を使ったり、何がどうなっているのかを考えたり、注意深く考える、といったことへの価値が減っているのだと思います。このことは学生にも見られます。形を作ったり、目標を達成することに関してはとてもモチベーションが高いのですが、じっと考えたり、不思議に思ったりすることへのモチベーションが低いのです。いや、そういった事ができないのかもしれない。どんなものであれ、彼らはすぐに何かを達成しようとしてしまう。こういった加速的な流れは、周囲のものへの可能性や注意力を低下させてしまうのです。

私たちは、まさに技術に魅了された時代に生きているわけなのですが、クレイジーな事ですよ。この20年、30年を考えてみて下さい。私たちは技術がもたらした驚くべき変化の目撃者なのです。インターネットも、宇宙旅行も、ソーシャルメディアも、以前にはどれも存在しなかったものです。そして今、私たちは技術によって未来や街や世界を変える事ができると信じているのです。そのことに疑いはありません。ですが、それが唯一の可能性だというわけでありませんし、ベストな方法だとは限りません。

森山さんの家での過ごし方を観察された中で、西洋の私たちにとって教訓になるようなことはありますか?

彼がいつも色んな方法で空間を探しているのには、驚きました。場所を変えるのが好きなんです。例えば、読んでいる本のテーマによっても場所を変えています。

1ページ、2ページと読み終わると、次のエピソードやチャプターに最適な場所を決めていくのです。私たちもやるべきですね。家具を動かしたり、配置を変えたり、いつもは行かない部屋のコーナーに行ってみたり。理由はなんでも構いませんが。

1、2年前になりますが、メンドリジオの学生が、彼とフラットメイトたちが、家の中の空間をどのように使っているのか、映画を撮影しました。3人全員の動きを記録し、そのデータから「空間利用」のダイアグラムを作ったのです。そこでわかったのは、使える空間のうち彼らは40%しか使っていないということでした。そこで、彼は家具の配置を変えて、3人がもっと空間を使えるようにしたのです。その実験後にまた、動きを記録したダイアグラムにして見てみると、今度は75%の面積を使っていることがわかりました。つまり、私たちの多くは、先天的に空間という概念を捉えてはいるということです。森山さんのように、空間の探求をしようとすれば、多くのことを学び発見できるのです。

若い建築家は、家庭的空間とはどのようなものかを理解する前提として、私たちに受け継がれている社会文化的なパターンを疑う姿勢を持つべきだと思うのです。私たちは、家というものが、どのように作られ、そこに住み、使われるべきか、ということに対して多くの固定観念を持ってしまっています。特定の空間での特定な機能や振る舞い方を想定してしまっているからです。そんな状況の中で、「そんなパターンなんか全部壊してしまって、自由を手に入れたいのだ。」と言ってしまうには、努力が必要ですし、意識的な決断が必要です。自分の正しいと思うこと、あるいはそうでないと思うことに逆らっていく強さが欲しいですね。子供の頃に戻って、人生の中で今までずっと言われてきたことを忘れる必要があるのです。子供はいつだって、びっくりするようなやり方で物を使いますよね。椅子とか、空間に関するものとか、なんでもです。子供は文化的に規定されたことから完全に自由な存在ですから、色んなものを探し出して、遊びに変えてしまうのです。

どうすれば森山さんのように、センスのある観察者になれるのでしょうか?

私たちには4歳になる息子がいます。ある日、彼に聞いてみたのです。「ベッドルームは好き?ベッドの位置はそれがいいかな?」彼にとって、その時の質問は奇妙なものに感じたと思います。私たちは、彼に生活に最も近い空間について考えてみて欲しかったのです。彼は答えました。「うん。でもなんでそんなこと聞くの?」私たちは伝えました。「変えたいなら変えてもいいのよ。部屋の反対側に置いてみようか?そうしたら、朝、窓から鳥とか雲とか見えるものね。」すると彼は「ああ、そうだね。ナイスアイデアだね。」と言ったので、私たちはベッドの場所を移動したのです。

数日後に、彼は私たちのところにやってきて、ベッドを元の位置に戻したいんだと、言ったのです。理由を尋ねてみると、元の位置からはドアが見えて、そこから私たちが入ってくるのが見えたのだと。そうです。この瞬間、彼は自分のパーソナルスペースがどうやって組織化されていたのかを考え始めたのです。私たちが、部屋に入ってくるのが見えると、心地よく安心するのだと気づいたのです。素晴らしいことでしょう。もし子供に、学校でもこういったこと、例えば部屋のレイアウトを変える練習などが教えられたら、子供たちは空間というものを意識し始めるでしょう。空間体験とは何であるか気づくはずなのです。その子供たちなら、20歳を過ぎ、街に出る頃には、こんな街良くないし、ちゃんと直さないと住めないよ、と言うでしょう。こういったことは、残念ながら過小評価されてしまっているテーマですね。小学校から、子供たちにこういった疑問を投げかけ、空間の物理的な組織化とそれに伴う心理的、そして感情的な作用に関して、集団的に意識を育むことができるとすれば、社会にも大きな変化をもたらすことができるのだと思うのですが。

この点で、森山さんは、子供のような無邪気さを持ち続けている人として、素晴らしい事例だと思います。家庭空間の文化的パターンによって構造化されたり、訓練されたりしていないのです。彼は私たちの求める繊細な観察者で、空間への参加者なのです。彼とともに暮らすことで、私たちが映画を撮っているときに理論化しようとしていることの全てに触れているのだと言えるでしょう。彼の中にすべてがあるのです。

私たちが、彼から学んだのは、彼のささやかな存在感、五感を駆使して瞬間を生きていく強さです。合理的な西洋の成人は、この開放的な状態を忘れがちなのです。私たちの文化では無邪気さと結びついてしまうからでしょう。無邪気さは、社会的制約によってあまりにも多く失われてしまっています。忘れ過ぎないように気をつけないといけませんね。

2021年10月13日

Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine: For a significant part of his life, Moriyama-San worked from home in a liquor shop owned by his mother. When his mother passed away, he decided to demolish her house and the shop to build a new house, in the exact same place. He was up to the idea of putting himself into an experiment and wrote a letter directly to the architect Ryue Nishizawa believing he was the right professional to challenge his hitherto way of life. Moriyama-San and Ila became friends through a common interest in Japanese noise music, that’s how Ila could stay with him in his house for a week during the summer of 2017.

HOW WAS HIS LIFE BEFORE?

The original house, if we understood well from what Ryue Nishizawa told us, didn’t have windows as such, as they were completely covered with shelves, filled with books. It was compact, closed and rather dark. Building a new house for Moriyama-San was in some way building a new way of life for him. He changed radically from a sort of a nerd, living in a dusty and slightly stifling environment, to a wild cat in a little urban forest.

Today, his domestic life is divided between separate living units spread over the small site. Some of them are only one floor, some have stairs that lead to higher levels. Some have some spaces underground as well. The house pushes him to move up and down and between the cubes in the open air, regardless of rain, snow, or wind. He constantly must step outside to go to the kitchen, or bathroom. This fragmented organisation of domestic life constantly provokes unconventional and surprising situations.

What in a more standard house would be considered as a living room, that is to say a central space unifying individual and isolated rooms is assumed by the small central garden. So, it’s the outside which plays this unifying role among smaller units.

BEING THERE, DID YOU FEEL PROTECTED, OR RATHER EXPOSED TO THE CITY?

In the film « Tokyo Ride » we shot with Ryue Nishizawa, he evokes in a particular way how different Japanese and Occidentals behave in regard to the idea of protection or exposure of the self in society. Westerners usually build their identity on the principle of the individual strength. They need to seem powerful and prepared for a social relationship perceived as a conflict. Even if they can behave in very cordial and diplomatic ways, they are constantly, even if unconsciously, envisioning the social interaction as a potential confrontation in which hierarchies of power are at play. On the contrary, Nishizawa presented the Japanese people as « disarmed », in the sense that they are not moved by such a pressure of conflict in the relation to one another. You can strongly feel this in the almost total absence of aggressiveness in Japanese cities. I am not fully sure it can also explain the appeal towards transparency in contemporary Japanese architecture, but it would be interesting to investigate this further.

On this point of protection or exposure in architecture, we have also been really amazed to understand how Japan deals, in general, with thermic insulation. Because of their hot and humid climate, traditionally they have conceived an architecture of porosity - to allow natural ventilation within a building. What is very surprising is that even today this idea of thermic porosity remains. Walls are often thin, fragile even, and when inside, you feel closely connected to the outside in terms of either temperature or sound. So, it means that in winter you get very cold and very hot in summer.

But this is also related to a larger fascination and respect towards nature and its strength in Japanese culture.

IT’S A VERY INTERESTING QUESTION, BECAUSE IT RELATES TO THE CULTURAL RULES DEFINING PRIVACY AND RESPECTING OTHERS.

The question of privacy is essentially a cultural definition which is understood very differently from one country to another. For instance, when we were in Copenhagen shooting a film in Bjarke Ingels’ 8 House, we experienced another variation on this paradoxical idea of « exposed intimacy ». Because of the lack of natural light during winter months in Denmark, there is a high preoccupation with light, people there have big windows with no curtains. In the evening, as a passer-by, you could see everything happening in the house, the most intimate family gatherings, people in their bedrooms, etc. The Moriyama House is very similar in this aspect. It is also built with huge openings, which merge the inside and the outside. It works well, because both in Japan and Denmark the culture is based on a high level of mutual respect. You see people passing by, neighbours on bikes, in cars, children running, old people walking, stopping, and so on. It’s an all-day sort of continuous flow but no one is supposed to peep in. The only ones who actually do, even in rather rude ways, are foreigners - as Moriyama San recounted to us. To avoid this, he has placed a board on the street, written in English, asking architecture tourists if they could kindly avoid stepping in the private area of the garden.

Despite the transparency of the large openings on the street side, the intention of Nishizawa was to slightly separate the owner from the city and create, thanks to the central small garden, a peaceful protected place and it has been achieved, but just in a very balanced, idiosyncratic way. You are neither cut off nor completely exposed. You always have a choice, and it gives a very pleasant feeling.

IN EUROPE, WHEN WE THINK ABOUT A CONNECTION OR HARMONY WITH NATURE, USUALLY WE IMAGINE BUILDINGS MADE FROM NATURAL MATERIALS. MORIYAMA HOUSE IS A SERIES OF ABSTRACT WHITE BOXES. WHAT EFFECT DOES THIS HAVE?

In this case architecture is a device to connect you with nature, but not necessarily a part of nature itself. The materials are not meant to have any rhetoric meaning or tell explicitly a story of belonging linguistically more to the garden rather than to the street. The house is minimal and left without any symbol of luxury, in order not to distract you from its main purpose. In terms of furniture and facilities, it offers the minimum Moriyama-San needs to live. For instance, the kitchen is used mainly to put beers in the fridge - but not to cook large meals for many guests or even himself. The house does not have what we would call a bedroom either which in truth, is extremely radical as sleeping on the floor was quite an experience.

In terms of our way of understanding a house, this house is a series of cubes, little rooms and angles that are dedicated to enjoying space and the present moment. It is not a technical device to answer all our needs or a manifestation of an ideology. It all works in such a simple and minimal way. Beyond its domestic functions, the way Moriyama-San lives this house is a place to experience the emotions produced by the subtle interaction between the space, the garden and the movement of people passing by.

WHY IS A HOUSE AN INTERESTING TOPIC FOR A FILM?

We figured out very early that most films on architecture were basically descriptive, focusing on the buildings’ aesthetic features, the materials, the structure, the various innovative features, etc.

In a word, an architecture film very often serves the specific role of being a promotional and communication tool for architects, and that induces necessarily a certain aesthetic with a sense of seduction in the way you make a film. In opposition to that, we have been looking to distort the relation of subordination between film and architecture, in order to find a real critical freedom which could open up a debate about how architecture is being represented. Film allows us to question the relationship we develop as human beings with our surrounding space. That’s why our main effort has been the one of placing people at the forefront of architecture’s representation to question architecture, its role and impact, from a more anthropological point of view. This led us to choose the house as the most interesting narrative device, because there is no other space we fill with more emotion, memories, and intimacy. The house is as much a spatial reality as a mental territory. This psychological richness made us understand that it was an endless reservoir of personal and moving stories.

IS THEN „MORIYAMA-SAN” A FILM ABOUT THE HOUSE OR ABOUT THE PERSON?

We’ve always tried to avoid filming the figure of the owner or the architect because they usually are excessively involved with the project, in an emotional way. They are acting, like in a theatre, and are rarely able to have sufficient distance to talk about the building in a natural and un-staged way.

Moriyama-San was an exception from the rule. He is not representing what we would call the typical pride of an owner. An occidental individual would be much more into social representation. In contrast, Moriyama-San was incredibly natural, and detached, breaking all cliches about the owners of buildings that are recognised as architectural achievements.

What’s marvellous about him is that he seems essentially interested in his house for his pure personal enjoyment, that’s quite unique.

The idea was to talk about the space through the way it is being lived and experienced. So very much about the physical and psychological interaction with space. Rather than talking about the qualities of a space in an abstract way, we like to explore those qualities through the sensorial and emotional relationship an individual will create with the space he inhabits. And Moriyama-San is exceptional for this. It was a revelation for us. It was probably the first time we were so closely and intimately immersed within a sensibility very new for us, so subtle, so refined in its attention to micro atmospheric phenomena and so many aspects we rarely pay attention to in our busy urban lives. He is certainly very Japanese in his sensibility, but this was our first close connection with Japanese culture, so we were really amazed how receptive they are in sensorial terms. In many moments of the film, you can understand that Mr Moriyama moves through the house, chooses where to sit, to lie down or to stay depending on the qualities of light, sound, wind, temperature, etc. His way through the building is led by this sensorial intuition rather than by functional necessities and that’s just marvellous. It was such an enlightening encounter for us. We learned so much from his ultra-sensitivity. It reinforced our conviction that the best way of recounting a space is through its fully immersive and intimate experience and this is precisely what cinema allows to do.

WHAT EXPERIENCES WERE YOU EXPOSED TO IN THE MORIYAMA HOUSE?

The scale of the house was very surprising. All these spaces are very small. You must physically adapt to enter them and move in a very precise and delicate way.

It calls for a sort of physical dialog with space like a precise choreography, otherwise you may bump into everything, knocking down objects and furniture upon each move. So, you must be extremely careful of how you move and where you step, because the house is also quite dangerous, there are no fences or railings. There are holes and large openings, very small ladder, etc. So it’s a sort of physical playground requiring to be in a constant state of alert. The house proposes a kind of sensory kaleidoscope where each place offers different conditions and requires different types of awareness.

The first feeling, as occidental adults, was that our body was deeply unadapted as we are more accustomed to large spaces. We are not used to master our movements in such a precise way, to fit to the small dimensions of a Japanese house. In the West, we also take it for granted that the architect cares about our safety, so we do not really pay attention. We really felt physically massive and a bit rough in the way we behave, so being there was undergoing a sort of re-education of body language. From childhood, Japanese are trained to adapt to the constraints of small scale and are thus much more measured and in control of their movements.

SO, YOU UNDERSTAND THE TRUTH OF A SPACE BY WATCHING HOW SOMEONE EXISTS IN IT?

Rather than « truth » I would say more its inner qualities. This intuition also became the direction we gave to our teaching at the AA, where we led a master studio entitled « Laboratory for Sensitive Observers ». This course intended to introduce students to the « art of seeing », in developing tools and methods to increase their skills of observation. The aim, on a larger scale, was to develop their sensitivity and understanding of the cultural features legible in our social behaviours, but also political and economic forces that are at play in our urban life.

Our intent was to raise awareness on how important the quality of observation and the sharpness of a site analysis, in the complexity of its socio-cultural and historical components, is what will make the students’ future proposals as young architects more accurate and relevant, with a strong human sensitivity.

DO YOU THINK THE CAPACITY OF OBSERVATION IS IN DANGER NOWADAYS?

We seem to live in an era of acceleration. There is great time pressure on the need to produce, to be very efficient and go straight to the point. There is perhaps, less value in the idea of taking stock, thinking what-is-what, and spending time understanding something for ourselves. We also saw this in our students, who are very motivated to produce forms or to reach a goal but less interested in, or unable to, linger on something, to wander. They try to quickly achieve something, whatever it is. And this acceleration goes together with a reduced attention and availability to what surrounds you.

We also live in an era of total fascination with technology, which is sometimes crazy. If you think about the last 20 or 30 years, we are witnesses to an incredible change brought about by technology. We have the internet, space tourists, social media, none of which existed before. Now we believe we can change the future, the city, and the world with technology. This is certainly true, but perhaps it’s not the only possible and not necessarily the best way.

WHAT IS YOUR OBSERVATION ON THE WAY MORIYAMA-SAN LIVES IN HIS HOUSE THAT COULD BE A LESSON FOR US IN THE WEST?

We were amazed to see that he continuously explores space in different ways. He loves changing place, even for instance, according to the subject of the book he is reading. He reads one or two pages and after that, he decides where to go to best fit the next episode or chapter. It’s something that we should also do in our own spaces - move furniture, change the arrangements, go to the corner that we never go to, regardless of reason.

One or two years ago, a student from Mendrisio made a film about how he and his flat mates used the space inside their house. He recorded the movement of everyone, 3 people, and used the data to make a ‘space use’ diagram. It showed that out of all the available space, they were using only 40 percent. He decided to change the layout of furniture to push the 3 people living there to use more space. After the experiment, he recorded their movements again, and his new diagrams showed that they used 75 percent of the area. It shows that most of us have in mind a conception of space that has been prepared for us. But if you try to explore, as Moriyama-San does, you can learn and discover a lot.

We believe young architects should be more prepared to put into question what we inherit in terms of socio-cultural patterns in the way we understand the domestic space. We have so many stereotypes of how a house should be organised, lived, and inhabited, with very specific functions and ways of behaving in certain spaces. It requires an effort, a conscious decision to say: “We want to disrupt all those patterns and introduce a certain degree of freedom”. It requires strength to go against what you consider right or not. You need to go back in time to when you were a child and forget what you have been told your whole life. A child always uses things in the most surprising ways, whether it is a chair or anything else related to space. A child will try to explore, to transform things into something to play with as he or she is still totally free from any cultural conditioning.

HOW CAN WE BE MORE LIKE MORIYAMA-SAN – HOW CAN WE BE MORE SENSEFUL OBSERVERS?

We have a son; he is just four years old. One day we asked him: “Do you like your bedroom? Do you like the position of the bed?”. For him, at that moment, it sounded like a very strange question. We provoked him to think about the space of his most intimate daily life. He said: “yeah, but why do you ask?”, we said, “We could change it, if you want. We could put the bed at the other end of the room, in the other direction so that you could look out of the window in the morning, see the birds or the moving clouds”, he said, “oh yes, that is a good idea”. We moved his bed.

Some days later, he came and told us that he would like to put the bed back like it had been before. We asked why and he answered, that before, he could see the door from where we entered. So, what happened in this very moment is that he started to think about the meaning of how his personal space was organised. He realised that he felt more secure, more comfortable when he could see his parents coming into the room. This is incredible. If you were to teach this to kids at school, with exercises of this kind, for instance changing the layout of their bedroom, they would start to be conscious of space – to be aware of what a spatial experience is. One day they would go outside into the city, when they are twenty years old or more and say that they cannot live in the city because it is not good, that it must be fixed. I think this is a topic that unfortunately is underestimated. If we could introduce from primary school that kind of questioning, to develop collective awareness regarding the physical organisation of space and its psychological and emotional consequences, it could make a big difference.

In this respect, Moriyama-San is an incredible example of a person who has maintained what we would call the innocence of a child. He is not trained or structured by any cultural patterns of domesticity. He is the sensitive observer and participant in space that we search for. We can say that living with him, we were exposed to all the things that we try to theorise about during the making of our films. We can find them all in him.

What we learned from him is his subtle degree of presence, an intensity in the way he lives the present moment through all his senses. As rational occidental adults we tend to forget this state of openness, which in our culture would be associated with innocence – too much is lost through our own social conditioning. But we should be careful not to forget too much.

13.10.2021

伊拉-贝卡和路易丝-勒莫奈: 在他生命中的大部分时间里,森山先生都在家里为他母亲开的酒 类商店工作。当母亲去世后,他决定拆除她的旧宅和商店,在原地建造一栋新的住宅。他想把自己投入到一种实验中,并直接给建筑师西泽立卫写了一封信,相信他正是挑战自己迄今为止的生活方式的专业人士。森山先生和伊拉通过对日本噪音音乐的共同兴趣成为了朋友,这就是为什么在2017年夏天,伊拉能够和森山先生一起在他的住宅里待了一周。

他以前的生活是怎样的?

原来的住宅,如果我们很好地理解了西泽立卫所说的,没有现在这样的窗户,因为它们完全被 架子覆盖住了,填满了书。它很紧凑,封闭,而且相当黑暗。为森山先生建造一座新房子,在某种程度上就是为他建造一种新的生活方式。他从一个生活在铺满灰尘、略显窒息的环境中的书呆子,彻底转变为都市小森林中的一只野猫。

今天,他的居家生活被分布在小基地上的独立生活单元所分割。有些只有一层,有些则有楼梯通向更高的楼层,有些还有一些地下空间。这所住宅促使他在露天的立方体之间上下移动,不论风霜雨雪。他必须不断地走到室外去,去厨房或者浴室。这种碎片化组织的居家生活不断引发非传统的和令人惊讶的情况。

在一个更标准的住宅中,客厅会被认为是一个中央空间,将各个孤立的房间统一起来,而这座住宅中,小小的中心花园却承担了这个任务。所以,是户外空间在这些小单元中扮演起了这种统一的角色。

在那里,你是否感到受到保护,或者说暴露在城市中?

在我们与西泽立卫拍摄的电影《东京之旅(Tokyo Ride)》中,他以一种特殊的方式唤起了,日本人和西方人在社会中自我保护或暴露的想法上会表现得多么不同。西方人通常在个人力量的原则上建立起他们的身份。他们需要显得强大,并为被视作冲突的社会关系做好准备。 即使他们能以非常亲切和变通的方式行事,他们也不断地,甚至是无意识地,将社会互动设想 为潜在的对抗,其中权力的等级制度在发挥作用。相反,西泽将日本人描述为"缴械式的",即 在相互关系中,对于这种冲突的压力,他们不为所动。你可以从侵略性几乎完全缺失的日本城市中,强烈地感受到这一点。我不完全确定这也能解释当代日本建筑中对透明性的诉求,但进一步研究这个问题会很有趣。

关于建筑中的保护或暴露这一点,我们也非常惊讶地了解到,一般来说,日本是如何处理隔热问题的。由于他们炎热潮湿的气候,传统上他们构思了一种充满孔隙的建筑——允许建筑内部自然通风。非常令人惊讶的是,即使在今天,这种导热气孔的想法仍然存在。墙壁通常很薄,甚至很脆弱,在里面,你会感觉到在温度或声音层面上与外界紧密相连。因此,这意味着在冬天你会感到非常寒冷,而在夏天则很热。

但这也与日本文化中更宏大的,对自然及其力量的迷恋与尊重有关。

这是一个非常有趣的问题,因为它关乎于定义隐私和尊重他人的文化规则。

隐私问题本质上是一个文化定义,在不同的国家有非常不同的理解。例如,当我们在哥本哈根BIG事务所的 8 House拍摄电影时,我们经历了关于 "暴露的亲密性 "这种矛盾想法的另一种情形。由于丹麦在冬季缺乏自然光,人们对光照的关注度很高,那里有着不挂窗帘的大窗户。 在晚上,作为一个路人,你可以看到房子里发生的一切,最亲密的家庭聚会,人们在自己的卧室,等等。森山居在这方面非常相似。它也是用巨大的开口建造的,将内部和外部融合在一起。这行之有效,因为日本和丹麦的文化都是基于高度的相互尊重。你看到路过的人、骑自行车的邻居、开车的人、奔跑的孩子、走路的老人、停下来的人,等等。这是一种全天的连续人流,但没有人会去偷看。唯一真正这样做的,甚至以相当粗鲁方式的,是外国人——正如森山先生向我们讲述的那样。为了避免这种情况,他在街上放置了一块用英语书写的板子,询问建筑业游客是否可以善意地避免踏入花园的私人区域。

尽管街道一侧的大开口是非常通透的,但西泽的意图是将业主与城市稍适隔开,并通过中央的花园创造一个宁静的保护地,这已经实现了,而仅仅以一种非常平衡、特异的方式。你既不被 隔绝也不完全暴露。你总是有所选择,它给人一种非常愉悦的感觉。

在欧洲,当我们考虑到与自然的联系或协调时,通常我们会想象由自然材料制成的建筑。森山住宅是一系列抽象的白盒子。这有什么样的效果?

在这种情况下,建筑是连接你和自然的一个装置,但不一定是自然本身的一部分。这些材料并不意味着有任何修辞上的意义,或明确地讲述一个在语言上更属于园子而不是街道的故事。为了不分散你对其主要意图的注意力,住宅是极简的,并且没有任何豪华的标志。在家具和设施方面,它提供了森山先生生活所需的最低限度。例如,厨房主要用于在冰箱里放啤酒——但不用于为许多客人甚至自己做大餐。这所住宅也没有我们所说的卧室,这实际上是非常激进的, 因为睡在地板上确实是一种不同寻常的经历。

就我们理解住宅的方式而言,这个住宅,正如你所说的,是一系列的立方体、小房间和角落,专门用来享受空间和当下。它不是一座满足我们所有需求的技术装置,也不是一种意识形态的体现。它全都由这样一种简单和的最低限度的方式运作。除了居家功能,森山先生在这所住宅 中的生活方式,是将其作为体验空间、花园和路人活动之间微妙互动所产生的情绪的场所。

为什么住宅是电影的一个有趣的主题?

我们很早就发现,大多数关于建筑的电影基本上都是描述性的,关注建筑的美学特征、材料、结构、各种创新特征等等。

一句话,建筑电影的特定角色往往是作为建筑师宣传和交流的工具,而这必然会推行某种美学,使你在拍摄电影时有一种引诱的感觉。与此相反,我们一直在探寻如何扭转电影和建筑之间的从属关系,以便找到一种真正的批判自由,从而能够开启一场建筑表现方式的辩论。电影使我们能够质疑我们作为人类与周围空间的关系。这就是为什么我们致力于把人放在建筑表现的最前线,从一个更人类学的角度质疑建筑、它的作用和影响。这导致我们选择住宅作为最有意思的叙事装置,因为没有其他空间能让我们充满更多的情感、记忆和亲密性。住宅既是空间现实,也是精神领域。这种心理上的丰富性使我们明白,它是一个无尽的个人的动人的故事宝库。

那么《森山先生》是一部关于住宅还是关于人的电影?

我们一直试图避免拍摄业主或建筑师的形象,因为他们通常以一种情绪化的方式过度地参与项目。他们在演戏,就像在剧院里一样,很少能够有足够的距离,以一种自然和非舞台的方式谈论建筑。

森山先生是这个规则的一个例外。他并不代表我们所说的典型的自豪感的业主。一个西方人会更喜欢成为社会性的表象。相比之下,森山先生是非常自然和超然的,他打破了所谓具有成就的建筑物的业主的所有陈规。

他的奇妙之处在于,他似乎热衷于自己的住宅,纯粹是为了个人的乐趣,这一点很独特。

我们的想法是通过居住和体验的方式来谈论这个空间。所以非常注重与空间物理和心理层面的互动。与其以抽象的方式谈论一个空间的品质,我们喜欢通过个人与其栖居地所产生的感官与情感的关系来探索这些品质。而森山先生在这方面是出类拔萃的。这对我们来说是一种启示。这可能是我们第一次如此密切又亲近地沉浸于对我们来说很新鲜的感觉中,如此精妙、细致地关注微小的大气现象和我们在繁忙的城市生活中很少关注的方方面面。他的感觉当然非常日本化,而这是我们与日本文化的第一次亲密接触,我们真的很惊讶于他们感官上的接受能力。在影片的许多时刻,你可以理解森山先生在住宅中的移动,根据光线、声音、风、温度之类的品质来选择坐、躺或待在哪里。他如何穿行于建筑是由这种感官上的直觉而不是功能上的需要来 引导的,这实在是太奇妙了。这对我们来说是一次充满启发性的邂逅。我们从他极致的敏感性中学到了很多。它加强了我们的信念,即叙述一个空间的最佳方式是通过完全沉浸式的密切体验,而这正是电影艺术所能做到的。

你在森山邸中触及到了什么样的体验呢?

这所住宅的尺度令人很惊讶。所有的空间都非常小。你必须在身体上适应步入其中,并以一种非常准确和精巧的方式移动。

这会唤起一种空间和身体上的对话,就像一支精确的编舞,否则你随时可能会撞到,每次移动都会碰倒物件和家具。你务必十分小心自己的移动方式和脚步,因为住宅也相当危险,没有围栏或扶手。这里有洞和大的开口,非常小的梯子等。所以它像是一种物理层面上的游乐场,需要时刻保持警惕。这所住宅提供了一种感官万花筒,每个场所给予了不同的条件,并要求着不同类型的意识。

作为西方成年人,我们的第一个感觉是身体上的不适应,因为我们更熟习于大空间,而不习惯以如此精确的方式控制我们的行动,以适应日本住宅的小尺度。在西方,我们也认为建筑师理应照顾我们的安全,因此我们不会很小心。我们确实感到自己的身体庞大,行为方式有点粗糙,所以在那里经历了一种身体语言的再教育。从孩童起,日本人就培养了对小尺度制约的适 应性,因此对自己的动作更有分寸和控制力。

所以,你通过观察人在其中的存在方式来理解一个空间的真相?

与其说是"真相",不如说是它的内在品质。这种直觉也成为我们在AA的教学方向,我们在那里指导了一个名为"敏感观察者的实验室"的研究生工作室。这个课程旨在向学生介绍 "观察的艺术",开发工具和方法来提高他们的观察技能。课程的目的,以更大的范围来说,在于开发他们的敏感性和理解力,针对于我们社会行为中可识别的文化特征,以及在我们城市生活中发挥作用的政治和经济力量。

我们的意图是提高对于观察的质量和场地分析的敏锐的重要性的认识,在社会文化和历史成分的复杂性中。这将使学生未来作为年轻建筑师的建议更加精准和贴切,具有强烈的人文敏感性。

你认为现今,观察能力式微吗?

我们似乎生活在一个加速的时代。对生产需求有很大的时间压力,要非常高效,直奔主题。也许,总结、思考什么是什么、花时间理解自己的想法,这些事情价值更小。我们也在我们的学生身上看到了这一点,他们非常积极地制作表格或达成一个目标,但对事情本身不太感兴趣, 或无法在上面流连,徘徊。他们试图快速的实现一些东西,无论它是什么。而这种加速伴随着对你周边事物的关注与获得的降低。

我们还生活在一个对技术完全着迷的时代,这有时是疯狂的。如果你想想过去的20或30年,我们见证了技术带来的不可思议的变化。我们有了互联网、太空旅行、社交媒体,这些都是以前不存在的。现在我们相信我们可以用技术改变未来,改变城市,改变世界。这是当然可行的,但这也许不是唯一可能的,也不一定是最好的方式。

你对森山先生在家里的生活方式有什么看法,可以作为我们西方人的借鉴?

我们惊讶地看到,他不断以不同的方式探索空间。他喜欢改变地点,甚至比如说,根据他正在阅读的书的主题。

他读了一两页,之后,他决定去哪里最适合下一段或下一章。这是我们在自己的空间里也应该做的事情——移动家具,改变计划,去我们从未去过的角落,不管是什么原因。

一两年前,一位来自门德里西奥的学生拍了一部电影,讲述他和他的室友们如何使用住宅里的空间。他记录了每个人的行动,3个人,并使用这些数据制作了一个"空间使用"图。它显示,在所有可用的空间中,他们只使用了40%。他决定改变家具的布局,促使住在那里的3个人使用更多的空间。实验结束后,他再次记录了他们的行动,他新的分析图显示他们使用了75%的面积。这表明我们大多数人心中都有一个已经准备好的空间概念。但是,如果你像森山先生那样努力探索,你可以学习和发现很多东西。

我们相信年轻建筑师应当准备好去质疑我们在社会文化模式方面所继承的对居家空间的理解方式。我们有很多关于住宅应该如何组织、生活和居住的刻板印象,裹挟着非常具体的功能和在某些空间的行为方式。这需要一种努力,一种有意识的决断,说:"我们想瓦解所有这些模式,并引入一定程度的自由"。它需要力量来反对你认为正确或不正确的东西。你需要回到你还是个孩子的时候,忘记你终生中被告知的事情。一个孩子总是以最令人惊讶的方式使用物品,无论是椅子还是与空间有关的其他东西。孩子会尝试探索,把事物变成可以摆弄的样子,因为他或她还完全不受任何文化制约。

我们怎样才能更像森山先生——我们怎样才能成为更有意义的观察者?

我们有一个儿子,他才四岁。有一天,我们问他。"你喜欢你的卧室吗?你喜欢床的位置吗? "。对他来说,在那一刻,这听起来是一个非常奇怪的问题。我们激发他思考他日常最亲密的生活空间。他说:“是的,但你为什么这么问?”我们说:“如果你想,我们可以改变它。我们可以把床放在房间的另一端,换一个方向,这样早上你就可以从窗户向外望,看到鸟儿或移动的云彩。”他说:“哦对,这是一个好主意。”我们移动了他的床。

几天后,他来告诉我们,他想把床放回以前的样子。我们问他为什么,他回答说,以前,他可 以从我们进来的地方看到门。因此,在这一时刻发生的事情是,他开始思考他的个人空间组织方式的意义。他意识到,当他能看到父母进入房间时,他感到更安全、更舒适。这真是不可思议。如果你在学校教孩子们这些,通过这种练习,例如改变他们卧室的布局,他们会开始意识到空间——意识到什么是空间体验。有一天,当他们20岁或更大的时候,他们会走到室外进入城市,说他们不能住在城市里,因为它不好,它必须被修复。我想这是一个不幸被低估的话题。如果我们能从小学开始引入这样的问题,以发展对于空间的物理组织及其心理和情感后果的集体意识,这可能会带来很大的改变。

在这方面,森山先生是一个令人难以置信的例子,他一直保持着我们称之为孩童的纯真。他没有受到任何家庭文化模式的规训或结构化。他是我们所寻找的敏感的观察者和空间的参与者。可以说,与他一起生活,我们接触到了所有我们在制作电影时试图理论化的东西。我们可以在他身上找到所有这些内容。

我们从他身上学到的是他微妙的存在感,强烈的通过所有感官活在当下。作为理性的西方成年人,我们倾向于忘记这种开放的状态,在我们的文化中,这种状态会与纯真联系在一起——丢失了太多由于我们自己的社会环境。但我们应当注意,不要过多的遗忘。

2021年10月13日

イラ・ベカ&ルイーズ・ルモワンヌ: 森山さんは、人生の大半を母親の経営する酒屋で働いていました。その母親が亡くなった時、家と酒屋を取り壊して、まったく同じ場所に新しく家を建てることにしたのです。彼は自分を実験台とする思いで、建築家、西沢立衛に直接手紙を出しました。彼こそが、今と変わらない生活に、新たなチャレンジを与えてくれるプロフェッショナルとして適任だと思ったのです。イラは、日本のノイズミュージックが好きだという共通点から森山さんと仲良くなり、2017年の夏に1週間ほど、彼の家に滞在させてもらったんです。

森山さんの以前の生活はどういうものだったのでしょうか?

元の家は、西沢さんが教えてくれたことから想像するに、部屋は、本で埋め尽くされた棚で覆われていて、窓がなかったようです。コンパクトで閉鎖的で、どちらかというと陰気な生活でした。森山さんにとって家を建てるとは、ある意味、彼の生き方を新しくすることでもあったのです。オタク的で、埃っぽく、窮屈な生活から、都会の小さな森の中で生活する野良猫のように彼の生活は激変したのです。

現在の彼の生活空間は、小さな敷地に散らばったそれぞれの住戸に分かれています。一層だけのものもありますし、上の階へと登れるものもあります。地下にあるものもありますね。雨の日も、雪の日も、風の強い日も、登ったり降りたりしながら、屋外にあるそれぞれのキューブの間を移動しなくてはいけないのです。キッチンやバスルームに行くには、外に出ないといけないですしね。このように生活空間が断片化された構成は、型破りで驚くような状況を提起するものです。

一般的な住宅においてリビングとして考えられる空間、つまり個々の独立した部屋をまとめる中心的な空間は、中央の小さな庭が担っているのです。そう、小さなユニットをまとめあげているのは外部空間だということです。

森山邸にいるときには、守られているような感じはありましたか?それとも都市に対して晒されているような感じがありましたか?

西沢さんと撮影した映画『Tokyo Ride』で彼は、社会の中で、自己を保護する、あるいは露出するという概念に対しての日本人と西洋人との行動の違いを、ユニークな視点から提起しています。西洋人は、たいてい個人の強さに基づいてアイデンティティを築いていくので、力強く見えることは、必要なことですし、対立的な社会的関係にも備えておく必要があるのです。非常に好意的に、そして外交的に振る舞うことができるのですが、そんな際にも常に、無意識にも、権力の力関係が作用している潜在的な対立を社会的な相互作用としてイメージしてしまうのです。それに対して、西沢は、日本人は「武装解除された」状態なのだと説明します。相手との相互作用によって生まれる対立的圧力に動機付けられた存在ではないということです。それは日本の都市に攻撃性がほとんどないことからも強く感じられることでしょう。日本の現代建築に見られる透明性へのアピールもそれが理由なのかどうかは、わからないのですが、関係性をもっと調べるのは面白いかもしれませんね。

建築における保護と露出という点では、日本での一般的な断熱の扱いには、とても驚きましたよ。日本は、高温多湿な気候なので、伝統的に建築は多孔性のものだと捉えられているのです。そうすると建物内での自然換気も可能ですから。さらに驚きなのは、この熱に対する多孔性という考えが今日においてもまだ残っているということです。壁は、たいてい薄くて脆く、室内にいても温度や音という点では、外と近く繋がっているように感じられるのです。冬はとても寒く、夏はとても暑いということです。

しかし、このことは、自然への興味や敬意と関係していることだと思いますし、それが日本文化の強みでもあると思います。

これは、とても面白い問題ですね。プライバシーや他者へのリスペクトは、それを定義づける文化的なルールに関連することですよね。

プライバシーの問題は、基本的に文化的な定義によるものですし、国によって捉え方は大きく異なります。例えば、コペンハーゲンでビャルケ・インゲルスの『8 House』の映画を撮影していたとき「晒された親密さ」という逆説的な考え方を経験したのです。デンマークでは冬の間、自然光が少ないこともあり、光への関心が高く、大きな窓にもカーテンをしない人が多いのです。だから夕方になると、通りすがりの人が、家の中で起きていることの全て、例えば家族の親密な集まり、寝室での様子など、を見ることができてしまうのです。この点では森山邸はとても似ていますね。大きな開口部があって、それによって内部と外部が混ざり合っている。日本にもデンマークにも、互いを尊重する文化があるからうまくいくのでしょう。通り過ぎる人、自転車や車に乗っている近所の人、走っている子供、歩いたり、立ち止まったりしているお年寄りなどを、絶え間なく流れるように1日中、見ることができるのです。ただし、覗き見をしてはいけないことになっているのです。実際に、覗き見してくるのは、外国人だけだと森山さんは話をしてくれました。中にはかなり失礼な人もいるみたいですが。それを避けるためにも、道に英語で書かれたボードを立て掛けて、観光客には、庭のプライベートエリアに足を踏み入れないようにお願いしているのです。

道路側への大きな開口部は、透明性を作り出しているのですが、西沢さんの意図は、住人を都市から少し切り離し、中央の小さな庭を利用しながら、平和で守られた場所を作り出すことにあったのです。それは、よくバランスのとれた奇妙な方法で達成されています。切り離してしまうのではなく、また完全に晒された状態でもなく。常にどちらにも選択肢がある状態で、それがとても心地よいのです。

ヨーロッパでは、自然との繋がりや調和を考えるときに、たいてい自然素材を使った建物を想像してしまうのですが、森山邸は抽象的な白いボックスの集合体ですよね。これにはどのような効果があるのでしょうか?

この場合、建築は自然とつながるための装置であって、必ずしも自然そのものの一部ではないということです。素材はレトリカルな意味を持っていませんし、言語的にも、家は道路側より庭の方に属しているのだ、とはっきり語っているものでもないのです。この住宅は、ミニマルで贅沢さの象徴などありません。主な目的から気が散らないようにしているのです。家具や設備に関して言えば、森山さんが生活する上での最低限のものは揃っています。例えば、キッチンは主にビールを冷蔵庫に入れるためだけに使われるものであっても、大勢のお客さん、あるいは彼自身のためにたくさんの食事を作るためのものではないのです。私たちが寝室と呼ぶようなものもありません。いや本当に、床に寝るのはとっても過激な体験でしたよ。

私たちの捉え方は、あなたの言う通り、この家は、ボックスの集合体なのです。小さな部屋、そして空間と今この瞬間を楽しむという考えです。あらゆるニーズに応えるような技術的な装置でもないし、イデオロギーの表明でもないのです。シンプルでミニマルな方法によって、全てうまく機能しています。住居としての機能を超えて、森山さんの暮らすこの家は、空間、庭、そして通り過ぎる人々の動きから生じる繊細な相互作用によって生まれる感動が、体験できる場所なのです。

映画にとって、なぜ家が興味深いテーマなのでしょうか?

建築に関する映画のほとんどは基本的に、建物の美的特徴や素材、構造、色々な革新的な機能などに焦点を当てた説明的なものであることに、私たちは早い段階で気づいていたのです。

一言で言えば、建築映画は、建築家のプロモーションやコミュニケーションツールとしての役割を担っている事が多く、映画の作り方は、必然的にある種の美学が誘発されてしまうのです。そのことに対抗して、私たちは、映画と建築の間の従属関係を歪めることで、建築がどのように表現され得るのか、という議論を展開する真の自由を見出そうとしてきたのです。映画は、私たちが人間として周囲の空間とどのような関係を築いているのかを問いかけてくれるのです。そういったことから、私たちの主な取り組みは、建築的表現の最前線に人間を配置し、建築の役割や影響をもっと人間学的な視点から問いかけることとなったのです。だから私たちは家を選ぶのでしょう。感情や記憶、そして親密さで満たされたような空間は、家以外には存在しません。家が最も面白くナラティブな装置なのです。家は空間としての現実でありながら、精神的な領域でもあります。この心理的な豊かさによって、家は、個人的で感動的な物語の無限の貯蔵庫であるということを理解するのです。

では映画『Moriyama-San』は、家についての映画なのでしょうか?それとも人についての映画なのでしょうか?

私たちは、所有者や建築家は、プロジェクトに関わりすぎていて感情的になっているので、いつも撮影しないようにしてきたのです。彼らは劇場で演技しているみたいになってしまいますし、自然に、演出的でなく建物について話せるほど十分な距離感を保てるケースはほとんどありません。

森山さんは例外でした。彼は、いわゆる典型的な所有者としてのプライドを見せつけたりはしないからです。西洋的な個人であれば、もっと社会的な見栄を張ってしまうのですが。逆に、彼はとても自然で、無頓着なのです。建築として認められた建物の所有者としては、常識を逸脱した無頓着さです。

彼が素晴らしいのは、純粋で個人的な楽しみのために、自分の家を面白がっているように見えることですね。すごくユニークなことですよ。

その空間での生活や経験を通して、その空間について話そうとしているのですが、それはつまり空間との物理的、心理的な相互作用が重要だということです。抽象的に空間の質を語るのではなく、そこに住む人が空間とともに作り出す、知覚的で感情的な関係性から、その特質を探求していきたいのです。森山さんはその点では群を抜いて特別な存在です。私たちは天啓を得たのです。微小な気温の変化や、忙しい都市生活の中ではほとんど気にかけないような事にも気づけるような、とても繊細で洗練された感性に、これほどまでに密接にそして親密に触れた経験は、ほとんど初めてのことでした。とても新鮮なものでした。彼の感性は確かにとても日本的なものだと言えるのですが、初めての日本文化との関わりでしたので、日本人の感性の受容性にはとても驚きました。森山さんが家中を動き回っているのは、映画のあらゆるシーンで見ることができると思います。光や音や風、それに温度の質などに合わせて、座ったり、寝転んだり、留まったりする場所を選んでいるのです。機能的な必要性からというより、知覚的な直感に導かれるようにして、建物の中を移動していくのです。単純にすごいでしょう。私たちにとってはとても啓発的な出会いでしたし、彼の超高感度な感性からはたくさんのことを学びました。空間を物語るための最良の方法は、空間への完全な没入とそこでの親密な体験を得ることであるという私たちの確信はより強いものになりました。そしてそれこそが、まさしく映画が可能にしてくれることなのです。

森山邸ではどんな体験を得られましたか?

家のスケールにはとても驚きました。あらゆる空間がとても小さいのです。中に入るには身体を調整しなくてはいけないですし、動くときは正確に慎重に動かなくてはいけません。正確なコレオグラフィーのように空間との物理的な対話が求められます。そうしないと、いろんなものに当たってしまいますし、動く度に家具やオブジェを倒してしまいます。だから、動くときや歩き方には細心の注意が必要です。家もかなり危険ですよ。フェンスや手すりもないですから。穴や大きな開口部、それにとても小さな梯子なんかはあるのですが。常に警戒が必要なフィジカルなプレイグラウンドみたいなものでしょうか。場所によって状況が異なっていますし、その都度、異なる意識が必要です。この家は、感覚の万華鏡のようなものですね。

西洋の成人として初めに感じたことは、身体があまりここに適応できていないということです。広い空間の方が慣れていますから。それに日本の家の小さな寸法に合わせられるほど、正確な身体の動きをマスターできていないのです。西洋では建築家が安全に気を配ってくれている事は当たり前ですから、こういったことに注意を払っていなかったのです。私たちの身のこなし方は、物理的にもがっしりしていて、荒々しいのだと感じました。そこにいると私たちの身体的言語が再教育されているように感じるのです。小さい頃から日本人は、スケールの制約に適応するように訓練されていて、自分の動きをもっと慎重にコントロールできるのでしょう。

人がどのようにその空間に存在しているのかを観察することで、その空間の真実を理解できると言うことでしょうか。

「真実」と言うよりは、「内実」という感じでしょうか。この私たちの直感は、AAスクールでの指導での方針にもなっています。修士学生のスタジオを持っていたのですが、タイトルを「感覚的観察者のラボラトリー」としたのです。このコースでは、観察力を高めるための道具や方法を発展させ「見る技術」を紹介していくことを目的としていました。より大きなスケールでは、私たちの社会的行動から読み取れる文化的特徴だけでなく、都市生活に作用している政治的、経済的な力への理解と感度を高めることを目的としています。

社会文化的、そして歴史的要素が複雑化する中で、質の高い観察力や、敷地へのシャープな分析力がいかに重要なことであるか気づいてもらう事を意図していました。これらが、若い建築家としての将来の提案を、人間的で力強い感受性とともに、より正確な、そして適切なものにしてくれるのだと思っています。

現代において、観察力が弱まってしまっているとお考えですか?

私たちは、加速的な時代に生きているようですね。生産性や効率性、そして目的へと直行することへの大きな圧力があるわけですが、何かを理解するために時間を使ったり、何がどうなっているのかを考えたり、注意深く考える、といったことへの価値が減っているのだと思います。このことは学生にも見られます。形を作ったり、目標を達成することに関してはとてもモチベーションが高いのですが、じっと考えたり、不思議に思ったりすることへのモチベーションが低いのです。いや、そういった事ができないのかもしれない。どんなものであれ、彼らはすぐに何かを達成しようとしてしまう。こういった加速的な流れは、周囲のものへの可能性や注意力を低下させてしまうのです。

私たちは、まさに技術に魅了された時代に生きているわけなのですが、クレイジーな事ですよ。この20年、30年を考えてみて下さい。私たちは技術がもたらした驚くべき変化の目撃者なのです。インターネットも、宇宙旅行も、ソーシャルメディアも、以前にはどれも存在しなかったものです。そして今、私たちは技術によって未来や街や世界を変える事ができると信じているのです。そのことに疑いはありません。ですが、それが唯一の可能性だというわけでありませんし、ベストな方法だとは限りません。

森山さんの家での過ごし方を観察された中で、西洋の私たちにとって教訓になるようなことはありますか?

彼がいつも色んな方法で空間を探しているのには、驚きました。場所を変えるのが好きなんです。例えば、読んでいる本のテーマによっても場所を変えています。

1ページ、2ページと読み終わると、次のエピソードやチャプターに最適な場所を決めていくのです。私たちもやるべきですね。家具を動かしたり、配置を変えたり、いつもは行かない部屋のコーナーに行ってみたり。理由はなんでも構いませんが。

1、2年前になりますが、メンドリジオの学生が、彼とフラットメイトたちが、家の中の空間をどのように使っているのか、映画を撮影しました。3人全員の動きを記録し、そのデータから「空間利用」のダイアグラムを作ったのです。そこでわかったのは、使える空間のうち彼らは40%しか使っていないということでした。そこで、彼は家具の配置を変えて、3人がもっと空間を使えるようにしたのです。その実験後にまた、動きを記録したダイアグラムにして見てみると、今度は75%の面積を使っていることがわかりました。つまり、私たちの多くは、先天的に空間という概念を捉えてはいるということです。森山さんのように、空間の探求をしようとすれば、多くのことを学び発見できるのです。

若い建築家は、家庭的空間とはどのようなものかを理解する前提として、私たちに受け継がれている社会文化的なパターンを疑う姿勢を持つべきだと思うのです。私たちは、家というものが、どのように作られ、そこに住み、使われるべきか、ということに対して多くの固定観念を持ってしまっています。特定の空間での特定な機能や振る舞い方を想定してしまっているからです。そんな状況の中で、「そんなパターンなんか全部壊してしまって、自由を手に入れたいのだ。」と言ってしまうには、努力が必要ですし、意識的な決断が必要です。自分の正しいと思うこと、あるいはそうでないと思うことに逆らっていく強さが欲しいですね。子供の頃に戻って、人生の中で今までずっと言われてきたことを忘れる必要があるのです。子供はいつだって、びっくりするようなやり方で物を使いますよね。椅子とか、空間に関するものとか、なんでもです。子供は文化的に規定されたことから完全に自由な存在ですから、色んなものを探し出して、遊びに変えてしまうのです。

どうすれば森山さんのように、センスのある観察者になれるのでしょうか?

私たちには4歳になる息子がいます。ある日、彼に聞いてみたのです。「ベッドルームは好き?ベッドの位置はそれがいいかな?」彼にとって、その時の質問は奇妙なものに感じたと思います。私たちは、彼に生活に最も近い空間について考えてみて欲しかったのです。彼は答えました。「うん。でもなんでそんなこと聞くの?」私たちは伝えました。「変えたいなら変えてもいいのよ。部屋の反対側に置いてみようか?そうしたら、朝、窓から鳥とか雲とか見えるものね。」すると彼は「ああ、そうだね。ナイスアイデアだね。」と言ったので、私たちはベッドの場所を移動したのです。

数日後に、彼は私たちのところにやってきて、ベッドを元の位置に戻したいんだと、言ったのです。理由を尋ねてみると、元の位置からはドアが見えて、そこから私たちが入ってくるのが見えたのだと。そうです。この瞬間、彼は自分のパーソナルスペースがどうやって組織化されていたのかを考え始めたのです。私たちが、部屋に入ってくるのが見えると、心地よく安心するのだと気づいたのです。素晴らしいことでしょう。もし子供に、学校でもこういったこと、例えば部屋のレイアウトを変える練習などが教えられたら、子供たちは空間というものを意識し始めるでしょう。空間体験とは何であるか気づくはずなのです。その子供たちなら、20歳を過ぎ、街に出る頃には、こんな街良くないし、ちゃんと直さないと住めないよ、と言うでしょう。こういったことは、残念ながら過小評価されてしまっているテーマですね。小学校から、子供たちにこういった疑問を投げかけ、空間の物理的な組織化とそれに伴う心理的、そして感情的な作用に関して、集団的に意識を育むことができるとすれば、社会にも大きな変化をもたらすことができるのだと思うのですが。

この点で、森山さんは、子供のような無邪気さを持ち続けている人として、素晴らしい事例だと思います。家庭空間の文化的パターンによって構造化されたり、訓練されたりしていないのです。彼は私たちの求める繊細な観察者で、空間への参加者なのです。彼とともに暮らすことで、私たちが映画を撮っているときに理論化しようとしていることの全てに触れているのだと言えるでしょう。彼の中にすべてがあるのです。

私たちが、彼から学んだのは、彼のささやかな存在感、五感を駆使して瞬間を生きていく強さです。合理的な西洋の成人は、この開放的な状態を忘れがちなのです。私たちの文化では無邪気さと結びついてしまうからでしょう。無邪気さは、社会的制約によってあまりにも多く失われてしまっています。忘れ過ぎないように気をつけないといけませんね。

2021年10月13日

Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine: For a significant part of his life, Moriyama-San worked from home in a liquor shop owned by his mother. When his mother passed away, he decided to demolish her house and the shop to build a new house, in the exact same place. He was up to the idea of putting himself into an experiment and wrote a letter directly to the architect Ryue Nishizawa believing he was the right professional to challenge his hitherto way of life. Moriyama-San and Ila became friends through a common interest in Japanese noise music, that’s how Ila could stay with him in his house for a week during the summer of 2017.

HOW WAS HIS LIFE BEFORE?

The original house, if we understood well from what Ryue Nishizawa told us, didn’t have windows as such, as they were completely covered with shelves, filled with books. It was compact, closed and rather dark. Building a new house for Moriyama-San was in some way building a new way of life for him. He changed radically from a sort of a nerd, living in a dusty and slightly stifling environment, to a wild cat in a little urban forest.

Today, his domestic life is divided between separate living units spread over the small site. Some of them are only one floor, some have stairs that lead to higher levels. Some have some spaces underground as well. The house pushes him to move up and down and between the cubes in the open air, regardless of rain, snow, or wind. He constantly must step outside to go to the kitchen, or bathroom. This fragmented organisation of domestic life constantly provokes unconventional and surprising situations.

What in a more standard house would be considered as a living room, that is to say a central space unifying individual and isolated rooms is assumed by the small central garden. So, it’s the outside which plays this unifying role among smaller units.

BEING THERE, DID YOU FEEL PROTECTED, OR RATHER EXPOSED TO THE CITY?

In the film « Tokyo Ride » we shot with Ryue Nishizawa, he evokes in a particular way how different Japanese and Occidentals behave in regard to the idea of protection or exposure of the self in society. Westerners usually build their identity on the principle of the individual strength. They need to seem powerful and prepared for a social relationship perceived as a conflict. Even if they can behave in very cordial and diplomatic ways, they are constantly, even if unconsciously, envisioning the social interaction as a potential confrontation in which hierarchies of power are at play. On the contrary, Nishizawa presented the Japanese people as « disarmed », in the sense that they are not moved by such a pressure of conflict in the relation to one another. You can strongly feel this in the almost total absence of aggressiveness in Japanese cities. I am not fully sure it can also explain the appeal towards transparency in contemporary Japanese architecture, but it would be interesting to investigate this further.

On this point of protection or exposure in architecture, we have also been really amazed to understand how Japan deals, in general, with thermic insulation. Because of their hot and humid climate, traditionally they have conceived an architecture of porosity - to allow natural ventilation within a building. What is very surprising is that even today this idea of thermic porosity remains. Walls are often thin, fragile even, and when inside, you feel closely connected to the outside in terms of either temperature or sound. So, it means that in winter you get very cold and very hot in summer.

But this is also related to a larger fascination and respect towards nature and its strength in Japanese culture.