ティボール・ヨアネリー:「Shinoharistics」の執筆を始める直前までは、3人の建築家と彼らの設計した3つの住宅についてのエッセイを書くつもりでいました。篠原一男、ルイジ・モレッティ、そしてもう一人です。ヨジェ・プレチニックか、シーグルド・レヴェレンツで迷っていたのです。結局、他の建築家たちと一緒にするには篠原の引力が強すぎて、彼と「谷川さんの住宅」だけに特化して執筆することにしたのです。ただ、プレチニックが非常に面白い対象であることには変わりなく、いつか「Plečnikistics」を書ける日を待ち望んでいました。

篠原一男とプレチニックの共通点はどんなところでしょうか?

最もわかりやすいのは、彼らの探求が母国の伝統と共鳴するもので、それが結果的に国のアイデンティティへと影響を及ぼしている、ということですね。篠原は、空間における日本らしさを追求していました。一方、プレチニックは首都リュブリャナの最も重要な公共空間を特徴づけました。それらは、当時まだ成熟していなかったスロベニアにおいて多くのシンボルとなったのです。もう一つの重要な共通点は、カルト的性質です。独自のスクールが形成され、多くの熱心な信者とともに彼らの思想に基づいた活動が行われていました。ただ、これらの事を除いて俯瞰して見れば、彼らは随分と異なるとは思いますが。

プレチニックの家は、周囲の古い家々の形成するシステムの一部になっているのでしょうか?それとも、緊密に編み込まれた既存の文脈に侵入する新参者といった感じなのでしょうか?

そうですね。どの時期のものかによるのですが、例えば、最初のデザインは篠原の「ハウスインヨコハマ」にとても似ています。月面に着陸してきたみたいですね。非常に集中的で特異なものです。その後、いくつかの要素が追加され、周辺環境と関係を持つようになりました。そのおかげで随分良くなったと思います。

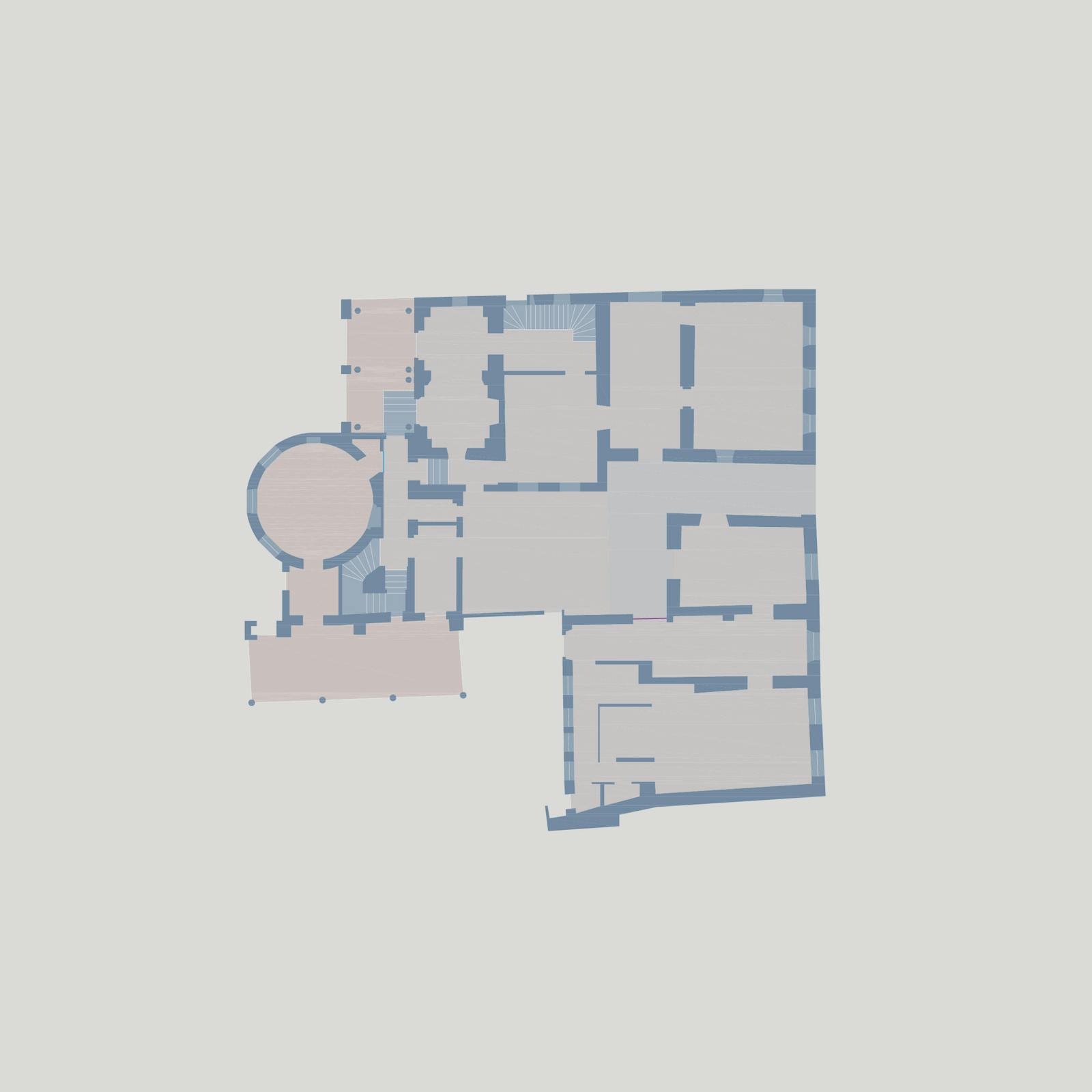

現在のアクセス動線では、細い路地を入ってから中庭に到達します。中庭は古い建物に囲まれていて、増築されたボリュームの正面が近くに見えてきます。冬の庭を通り過ぎると、中庭が広大な土地に向かって開いていることに気づきます。プレチニックの住んでいた増築部分は、教会の敷地に隣接する庭へと向かって方向づけられているのです。以上が最初の、ごく基本的な状況の解読です。

プレチニックは自分自身、そして兄弟のために敷地を買ったらしいのですが、残念ながら共同生活は叶いませんでした。当の建築家があまりにも繊細で、邪魔されることに耐えられなかったからです。彼は、他人の存在や共同作業を頼りにしながらも、仕事や考えに集中できる人里離れた生活を必要としたのです。

この家自体が、その逆説的な状況を反映しています。文脈的統合 - 古いものと新しいものを形式的に、そして機能的に融合すること- と、野心的自律性 - 個人的な趣向や好みによって超特定の個人のために空間を構築すること- とが一体となっているのです。

この家は単に周囲との関係を持つだけでなく、より広域な都市とも関係をもっているのです。リュブリャナの美しい街並み、リュブリャニツァ川につながるプロムナード、そして図書館などは、全てこの家の中で構想されました。この家自体が建築的断片の実験場となっていたわけです。

デザインを考えては、モックアップを作って庭に置き、うまくいっているかどうか見え方を確認していました。プレチニックは、都市計画の模型を保管し、家の階段や二階の製図室に飾っていました。それらの模型を通して、家の中にはまさに都市が立ち現れていたのです。それに彼はアンティークを集めることに夢中でした。その多くは彼の経験と関係のあるものでした。これらの影響が、次々にリュブリャナ全体へ広がっていったのです。プレチニックは、まさに家と都市、現在と過去との間に、ある種の新陳代謝を起こしたのです。

この家が、都市全体を揺るがす文化的な震源地となっていたということでしょうか?

そんな感じだったのでしょうね。当時のリュブリャナやスロヴェニアで起こっていた文化的な変化についてはあまり詳しくないのですが。この家が、その変化を加速させる媒介となっていたことは確かだと思います。

一個人でありながら、プレチニックの私的な関心が極めて公的なものへとなっていき、その逆に、都市が彼の家の中へと現れてくるようになってきた。それが、私がとりわけこの家を興味深く思う理由ですね。ユニークなものでありながら、実に多様な文脈との対話の中でこの家は存在しているということです。

プレチニックは、通りの公共性から意識的に離れて、庭に向かって住むことを決めました。隣接する教会との親密な関係があったからです。以前の庭は、ごく普通の実用的なもので、東の方ではどこにでもあるものでした。古い村の敷地やちょっとしたブルジョア階級の家にあるようなものです。庭は、食料を育てたり、動物を飼ったりするためのもので、必要不可欠な資源でした。プレチニックは、庭と既存の家を高貴に仕立てて、庭の意味をガラッと変えたのです。

その態度は、古典主義的な城のような佇まいをした庭によく現れています。その態度が、奇妙な二分法をも作り出しているわけですが。つまり、自分自身のための非常に閉じられた世界がそこに作られている一方、そこに住む建築家は都市に参与し、より広い文脈へと開かれている、という態度です。興味深いことに、この庭には今でも植物が植えられていて、隣人が好きに栽培できるようになっています。

家に至るまでのアクセスについては、言及する必要がありますね。当時は、大通りから古い家を通り抜けていく方法ではなく、教会の庭に沿った道から家へとアクセスしていたのです。お客さんや学生、それにクライアントまでもが建築家の家へ行くために、教会の領域を象徴的にも横断しなくてはいけませんでした。そして、ベランダでときには何時間もの間、待ち続けるのです。ドアが開き、建築家が出迎えてくれる時を。日常生活を舞台化する、非常に建築的なアプローチですね。とても演劇的です。若い学生であった私は、そこに魅了されてしまいました。家の周りを自由に歩くことはできないのです。建築的な配置が、ある種の強制的な儀式を作り、そこであなたは振り付けを演じるように動くわけです。強力な引力を感じました。トラクタービームのように。宗教的な参与への引力です。私自身は、無神論者だと思っているのですが。(洗礼も受けてませんから。)

儀式という言葉は、具体的には何を指しているのでしょうか?

モダニズム以前には、あらゆる古典的な文化の中に偏在していたものです。プレチニックの感性は、それらに深く根付いていましたし、彼は建築のシークエンスにおける儀式的な可能性を理解していたのです。

例えば、入り口のベランダは単なる入り口ではなく、アクロポリスへ入るときのプロピュライア的な役割が与えられていて、入るという行為が儀式への参列へと変化するのです。プロピュライアは、彼の作り上げたリアリティと、その周囲のもの全てとを区別するために、いつも使われていた手法です。サスペンスと緊張感がもたらされ、移行のための神聖な場所が整えられるのです。

彼の考えたほとんどの建物には、大きく、重く、そして黒い柱と、神聖な通り道が作られています。それらはフレームであると同時に彼の計画の中へとあなたを誘うものなのです。

メインルームが円形なのは、なぜだとお考えですか?

バロックの城のメインホールが、庭へ向かって突き出ているのを参考にしていることは確かだと思います。三つの窓と円形が非常に強いシンメトリーを作り出し、外へ向かって強い軸性を生み出しています。さらには、その上に長方形の屋根が被さっているので、奇妙なプロポーションをした独立柱のようにも思えますし...柱に取り憑かれた建築家が柱の中に棲みつく。なんて印象的でウィットに富んだイメージなのでしょう !

円形は非常に集中的な形でもあるわけですが、彼は、そこに多様な活動をつなぎ合わせる接点を探っていったのです。面白いですよね。あることに人生の全てを費やしたり、打ち込んだりしたくても、身体やそこへ至る過程には無理が生じてしまうのが普通ですから。プレチニックは彼の全人生、そしてある限りの創造性をこの一つの空間へと集中させたのです。想像するに、ドアの枠の上に重い梁が取り付けられているのもそのためでしょう。その梁が休むための空間と働くための空間とを象徴的に分けているのです。

もう一つ考えられる理由は、もっと形式的なものです。つまり彼は、イタリアの格式高い建築とリュブリャナやその周辺の粗末で農村的な建築のどちらにも強く影響を受けていました。彼は地方の村をたくさん訪れていました。ですから、このシリンダー状の形は、それらの地方の典型的な城の搭から来ていると考えることもできますね。おそらくスピリチュアルな事とも関係するのでしょう。信仰の砦という言葉は、プレチニックの時代によく使われたメタファーでもあるのです。

全く正反対な二つの空間のコントラストが興味深いのですが、どうお考えですか。つまり、仕事と睡眠のための中央の円形の部屋と、ガラス張りの細長い長方形のベランダの二つの空間の関係についてどうお考えかお聞かせください。

建築の歴史において中心的な空間というのは、通常、神への献身や完璧性を意味しますよね。一方、対称性や集中性のない幾何学というものは、自然や都市に現れてくるものですし、儀式性のない、もっとリラックスした形で機能するものです。この家においては、二種類のタイプの部屋が一直線上に繋がっていて、一方からもう一方へと簡単に移動することができるようになっています。

プレチニックは、家は教会と同じ設計原理で建てられるべきだと考えていました。そう、彼の家の主な建築的形態は、神聖な空間を意味しているものです。方向づけられているものでもなく、誰かと一緒にいるための空間でもない。円という絶対的な形が、空間に自律性を与え、それゆえに教会の空間と似てくるわけですね。古典的な設計の考え方からすると、家というものは、もっと他の要素、いわば絶対的でない要素によって、周囲と繋がりを持つ必要があると考えるべきなのです。だから、構成的にこの家を考えると、とても面白い。メインスペースと周辺環境とは、一定の距離を保っていますよね。あるいは、中間的な空間によってフィルターがかけられているという感じでしょうか。

これらの外部空間がアンカーとなり、家を周辺の文脈の中に結びつけているのです。玄関への小道、教会、庭、そして実験用モックアップで溢れた畑との密接な関係を作り出しているのです。これらが家をある種のエコシステムへと組み込んでいるわけです。家は要素ごとに分解されてしまうものではなく、全てが融合しつつも、個々の要素が認識され得る状態にあるのです。つまり、それぞれの実体や性質が保持されながらも、有機体である臓器のようにそれぞれが支え合って役割を担っているのです。

篠原も相反する空間をつなぎあわせて、コントラストや突然の変化を強調する操作をしていたと思います。一方、プレチニックには、根本的に異なる性格の空間を組み合わせながらも、調和や安らぎを作り出そうとする努力が感じられるのですが、どう思われますか?

篠原も象徴空間と機能空間とを区別していますね。しかし、コンセプトの明確さにおいては、プレチニックとはかなり異なります。趣味や性格の問題だと思うのですが。篠原はとても「Sushi」的な人なのでしょう。寿司では全てがあるがままという感じですよね。魚と米とをくっつけるのですが、それらを媒介する要素は何もないわけです。ソースもありません。醤油は、一貫ずつ後からつけるものですしね。

個人的には、プレチニックは全くそういう人ではないと思うのです。彼はGesamtkunstwerk(総合芸術)を求めていました。伝統と象徴との関係に依拠しながらも、細部まで構想しつくし、構成されたシームレスで一貫性のある建築を求めたのです。篠原は、矛盾や亀裂などの概念に依拠していたと思いますが。

プレチニックの設計方法を理解するには、一階の応接室が重要です。ごく限られた親しい友人だけが招かれた場所です。建築家は、かなり人を選別していたようですね。他の人は、ただ待たされたのです。この応接室は、他とは異なる特別な雰囲気のものでした。それでも、この部屋はしっかりと全体的なデザインコンセプトの中に組み込まれているのです。空間同士の間に強いコントラストを感じずに流動的な体験ができるのは、おそらく一人の建築家の手によって作りこまれているからなのでしょう。重要なのは「手」という言葉です。篠原の場合は、もっとコンセプチュアルでしょう。クラフト性やドローイングというよりは、心や知性に訴えかけようとするものです。彼は、家が数学をするかのように、対立や分割、そして差異を求めるのでしょう。

プレチニックの場合は、背景の精神的なアイデアが全てを統一しているのです。もちろんそこには宗教や、彼の出自としての分離派のGesamtkunstwerk(総合芸術)のアイデアが関係しています。建物は形式的な概念ではなく、精巧なディテール、精緻な素材の利用、そして要素同士の均衡関係、などに労力がかけられることで、少しずつ統合性を獲得していくものなのです。つまりプレチニックはドラフトマンなのです。篠原が数学者であるのとは対照的ですね。まあ、篠原のデザインにもスケッチは重要な役割を果たしているのですが。

この家は、おばあちゃんでも住みたいと思えるものでしょうか?

ええ、もちろん。それは建築の表現とも関係していると思います。建築的な要素があなたにダイレクトに訴えかける、そんな建築なのです。柱を見れば、あなたは柱と対話を始めますし、彫刻を見れば、あなたの視線と彫刻とが絡み合うのです。プレチニックは抽象化することに全く興味がなかった。彼の家は理解しやすいですし、単純に住みやすい。家庭的でさえある。

とはいえ、装飾や中のオブジェがなくてもこの家は成立すると思うのです。古典的なボキャブラリーがなくなっても問題ないでしょう。プロポーション、素材、境界の作り方、それに心地よさの点において、非常にうまくできています。

こういった点がプレチニックをモダニストたらしめているのでしょうか?それともまだ彼は、保守的でセンチメンタルな伝統に属していると思われますか?

彼の家の場合、既存の文脈を捉えながら、その姿を完全に作り変えてしまう、そういった建築の遂行態度が極めて現代的なのです。個々の部屋を見ると、どれも外部空間との関係を持っていますよね。これもまた非常に現代的な考えです。ところが、古典的な形態、古典的な構成、そして伝統的な要素は、数えればきりがないほどです。

つまり、どちらでもあるという感じですか。彼は、リュブリャナ市から直接依頼があったわけでもなく本能的に、リュブリャナを作り変える計画を始めているのです。二、三人でビールやワインを飲みながら議論していたのでしょう。信仰や、リュブリャナという都市についてや、スロベニアのアイデンティティ全般についてなどを話し合っていたのです。街をより良く、より美しくするために彼らは共に活動していました。プレチニックはただデザインを進めていきました。そして自ら街を作り変える責任を負ったのです。とても先進的な手法でした。市からの依頼ではなかったわけですから。お金が得られるわけでもなく、ただ進めていったのです。

一方、プレチニックは極めて古臭い人間でした。進歩や変化を受け入れてはいましたが、重要だとは思っていませんでした。それは、彼の信仰が原因だと思います。信仰の仕方もまた非常に古臭いものでしたし、ガウディとよく似ているのです。作品においては、どちらも最先端のアイデアを生み出しているのですが。

プレチニックは、アバンギャルドとしてのモダニズムのドグマに対して消極的であったようです。一方、馴染みのある形態を新しく配列し直すことで、周囲の環境を全く作り変えるといったことにはオープンな考えを持っていました。それは、本質的に非常に現代的なものなのですが。つまり逆説的にも到達点が同じなのです。

このことを、彼の信仰と正確にリンクさせていくことはできませんが、信仰との結びつきがとても生産的なものであったことは確かです。ガウディのことも一緒に考えると、私たちの時代における「クリエイティビティ」とは違う意味での「クリエイション」という言葉が、彼らの世界に対する意思の源であったように思えるのです。そのクリエイションを、人間的で自然な本性に由来するものだと考えるのであれば、それは今でも私たちの時代と確かに関係しているのです。トートロジーを承知の上で、ですが。ここで言及しているクリエイションとは、ブルーノ・ラトゥールが言うような、地上にあり、地球に束縛されたものに関わる概念としてのクリエイションです。

あなたが好きで良く知っている住宅の中で、プレチニックの家とは、性質や根本的な考え方が正反対なものはありますか?

正反対なものを探すとすれば、周囲から隔絶された家を選ぶことになりますし、それが主なポイントとなるでしょうか。建築のためだけに存在する建築。つまり極度に自律的な建築です。行ったことのある中でよく知っているのは、モスクワのコンスタンチン・メルニコフのアトリエ兼住宅ですね。19世紀末から20世紀初頭の周辺環境からは見事に孤立しています。特定の場所や文脈のためというよりは、理想的な型として設計されたものです。つまり文脈とは何の関係もない。

いや、もっと正確に考えると、社会的、政治的、あるいは具体的で、物質的な文脈という意味においては、もちろん文脈的な産物です。でもまあ、否定的に捉えれば、未来から降ってきたような家ということです。

プレチニックの家が興味深いのは、そこが家庭そのものであるからです。ラ・サラチェーナやコルビジェの小さな家、あるいは谷川さんの住宅が持つような住居性を超えたものです。私はいつも立ち返ってこのことについて考えるのですが、つまりそれはエコシステムなのです。建築家はそこに住んでいました。表現のスタイルや建築的エレメントを、家の中や、家の周りで試していたのです。アアルトがアトリエでやっていたようにです。プレチニックは、はじめに家の周囲を作り直し、次に家の庭と教会の庭との関係を作り直しました。そして都市との関係を考え始めたのです。この家は、家庭的なものであると同時に、より広域なネットワークの中での、ある種のノードとして機能しているのです。個人的なものでありながら、真の意味でパブリックなものですから。

2021年12月04日

Tibor Joanelly: Shortly before starting work on Shinoharistics, I had intended to write an essay about three architects and three houses they had designed. The collection was to be Kazuo Shinohara, Luigi Moretti and a third one. At the time, I was never sure, whether to write about Jože Plečnik or Sigurd Lewerentz. In the end I figured out that Shinohara’s gravity was just too strong to combine with others, so I decided to write specifically about him and Tanikawa house. Nevertheless, Plečnik remains a very interesting subject and one day, I can imagine writing Plečnikistics.

WHAT DO KAZUO SHINOHARA AND JOŽE PLEČNIK HAVE IN COMMON?

Most obviously, their research resonated strongly with a national tradition and consequently influenced the sense of identity of each of their respective countries. Shinohara looked for the Japan-ness of space, whereas Plečnik defined the character of the most important public spaces in his capital city, Ljubljana and became the author of many symbols taken up by a then young Slovenia. Another important similarity between their characters is the cult of the master that they created around themselves, establishing schools and movements founded on their own ideas, with significant numbers of devoted followers. However, apart from these things, I think, they were overall rather different.

IS PLECNIK’S HOUSE PART OF THE SURROUNDING SYSTEM OF OLD HOUSES THAT IT IS FOUND AMONGST, OR IS IT A NEWCOMER, AN INTRUDER IN THE EXISTING TIGHT NIT CONTEXT?

Well, that depends which version you refer to, for instance, the first design was very close to Shinohara’s House in Yokohama, a kind of moon lander. It was very centralised, very singular. In the later versions, the project, thanks to some additional elements, became more linked to the surroundings. I believe this made the building much better.

Today, you enter through a very narrow alley and arrive to a courtyard flanked by the old building and closed on the front side by the volume of the later addition, designed by Plečnik. If you pass by the winter garden, the courtyard opens towards a big piece of land. The new part, where Plečnik used to live, is oriented towards the garden, adjacent to the yard of the church. This is the first, very basic reading of the situation.

The story goes, that he bought the plot for himself, his brother and sister. Unfortunately, their cohabitation didn’t really work out because the architect was very sensitive and could not be disturbed. Although he depended on both the presence and work of others, Plečnik really needed a concentrated, secluded life in order to work and think.

The house itself reflects this paradoxical situation. It blends contextual integration - formally and functionally melding the old with the new, and an ambitious autonomy - building a space for a very particular individual, taking into account many personal fascinations and preferences.

The house relates not only to its immediate context. It is also connected to the wider city. Beautiful parts of Ljubljana, the whole promenade following the Ljubljanica, the library etc. were all conceived in this house, and the house itself became a testing ground for architectural fragments. Once designed, elements were mocked up and placed in the garden to check how they looked and if they worked or not. Plečnik also used to keep the models of his projects for the city, displaying them in the staircase and in the drawing room upstairs. Through these models the city became very present within the house. And he obsessively collected antiques, often related to his own experience. These influences were in turn spread all over Ljubljana. Plečnik really established a kind of metabolism between house and city, between present and past.

WAS THE HOUSE THE EPICENTRE OF A CULTURAL EARTHQUAKE, SHAKING THE WHOLE CITY?

It has a quality like that, although I don’t know too much about the cultural transitions that Ljubljana and Slovenia went through at that time. But in this context, the house must have become a kind of medium by which the cultural transformation was gaining momentum.

Although a private man, ultimately, Plečnik’s personal interests became extremely public – and vice versa, the city became present in the house. It is for this reason that the house remains, for me, interesting. At the same time the house is both unique, and in dialogue with completely diverse contexts.

Plečnik consciously cut himself off from the publicness of the street and decided to live towards the garden, in an intimate relationship with the adjacent church yard. Before, the garden was ordinary, utilitarian, as one finds everywhere in the east, in the yards of old villages or petty bourgeois houses. The garden served for growing food or keeping animals, it was an essential resource. But Plečnik completely changed its meaning by ennobling both, the yard, and existing houses.

This attitude is well expressed in the garden at the side of the house which exudes a classicist castle-like attitude and creates a strange dichotomy – at once being a very closed world, known only to itself, whilst, through the architect’s lived commitment towards the city, opening to a much broader context. Interestingly, the garden was still used for growing plants, for which neighbours were welcomed to cultivate for their own purpose.

It’s important to mention, that the main access to Plečnik’s house was, at that time, along a path that follows the border of the church yard and not through the old house from the street. His guests, students and for that matter, clients had to symbolically cross the domain of the church to access the architect’s house. There they had to wait on a veranda, sometimes for hours until he came to the door and greeted them. I think, it’s a very architectonic approach to staging everyday life - very theatrical. As a young student this is what attracted me to it. You cannot really move around the house without practicing a kind of enforced ritual, choreographed by the architectural arrangement. And I feel a strong pull – like a tractor beam – towards such a religious commitment, although I consider myself an atheist (I’m not even baptized).

WHAT DO YOU REFER TO WITH THE WORD RITUAL?

Ritual was omnipresent in all classical cultures before modernism. Plečnik was deeply rooted in them and understood the potential of rituals in the sequencing of his architecture.

For instance, the entrance veranda is much more than just an entrance. It’s like entering the Acropolis, you have a sort of Propylaea, entering becomes a procession. The propylaeum is a topic that Plečnik used almost everywhere to differentiate the reality he built from everything around. It introduced a suspense, a tension and set a solemn place of transition.

In almost every building he drew, you have the large, heavy, black columns and a sacred path that both frame and lead you into the plan.

WHY DO YOU THINK THE MAIN ROOM IS CIRCULAR?

There is surely a reference to the main hall in a baroque castle, projecting towards the garden. Together with the three windows, the circularity creates a very strong symmetry and a very strong axis towards the outside. And, beyond that, the house, with the rectangular roof, reminds a free-standing column with strange proportions… An architect with a fascination for columns himself inhabits a column – what a striking, witty image!

The circular shape is also a very concentrated form. He used it to explore the close connection between different activities. It is interesting, because even if your ambition is to completely dissolve your life in a discipline or dedicate yourself completely to something, the opposition of bodily needs and the creative process remains. Plečnik concentrated his whole life, his whole creativity within this one space. I assume, that’s why he introduced a heavy beam, resting above the door frames. Symbolically, it separates the space for rest and the space for work.

Another reason that comes to my mind is more formal. He was strongly influenced by both high Italian architecture and the more rudimentary peasant architecture of Ljubljana and its surroundings. He travelled and visited many local villages. The cylinder could be seen as the tower of a castle, typical of that region. I guess, it also had something to do with spirituality. The stronghold of faith was a popular metaphor in the times of Plečnik.

I FIND THE CONTRAST BETWEEN TWO COMPLETELY OPPOSITE SPACES INTERESTING. NAMELY, THE COMBINATION OF THE CENTRAL CIRCULAR ROOM, A PLACE OF WORK AND SLEEP, WITH THE VERANDA - A RECTANGULAR COMPLETELY GLAZED AND ELONGATED SPACE.

A central space in architectural history was usually meant to be a space of cult, of dedication to divinity, of perfection. Less symmetrical, less concentrated geometries were often more exposed to the nature or to the city, working in a less ceremonial, more relaxed way. Here the two types of rooms are connected along one straight line, you can just switch from one to another very quickly.

Plečnik believed that a house should always be built according to the design principles of a church. It means, that the primary architectural form of his house is meant to be a sacred space. It’s not directed, it’s not even a space to be together. It has the absolute form of the circle, which gives it autonomy, therefore makes it resemble the space of a church. The classical approach to design tells us that it needs to be connected to its surroundings by other, so to speak, less absolute elements, which, in my opinion, makes the house very interesting from the point of view of composition. You have the main space and the surroundings, kept at a distance, or filtered through a series of intermediate spaces.

These external spaces link the house to its context, like an anchor. They establish close relationships to the entrance path, to the church, to the garden, and to the field full of experimental mock-ups. They make the house a kind of ecosystem. The house doesn’t really fall into parts, everything is fused, but you can still read the individual elements. They keep their own substance, and their own character, like organs of an organism where each one plays a supportive role.

SHINOHARA TOO WORKED WITH BRINGING TOGETHER CONTRADICTORY FEATURES OF SPACE, STRESSING THE CONTRASTS AND ABRUPT CHANGES, PLEČNIK, AS WE CAN SEE EVEN NOW, ALSO COMBINED SPACES OF RADICALLY DIFFERENT CHARACTERS, BUT THERE IS A GREATER ENDEAVOUR TO ACHIEVE HARMONY, A STATE OF REST BETWEEN THINGS.

Shinohara also distinguished between “symbolic” and “functional” spaces. But the conceptual clarity with which he did that, separates him from Plečnik. I think it’s a question of taste or personality. Shinohara was a very „sushi” kind of person. In sushi you leave everything as it is, you combine fish with rice without any mediating element, without sauce. Soy sauce is added afterwards when you pick the Sushi piece by piece and dip it.

Personally, I think Plečnik was completely different. He searched for a Gesamtkunstwerk, for a building conceived and composed to the last detail and seamlessly coherent, all relying on tradition and symbolic relations. Shinohara relied on concepts of contradiction, fissure etc.

To understand the way how Plečnik was designing, the reception room on the first floor of his house is important. Only very close friends were invited there – the architect seems to have been very selective. Others had to wait. The reception room had a special and different atmosphere than the rest of the house. However, it was embedded within a total design concept. I would say, there are no strong contrasts between the spaces, experiencing them happens fluidly because they are so much shaped by one architect’s hand. And the word „hand” is crucial here. With Shinohara, it’s much more conceptual, I would say, it’s more about mind and intellect and much less about craft or drawing. With Shinohara, he is always searching for oppositions, divisions, differences, as if a house was doing mathematics.

In Plečnik there is rather a kind of spiritual idea behind his moves, that holds everything together, which is, of course, embedded in religion and related to the idea of Secession Gesamtkunstwerk, where he comes from. The building slowly acquires its integrity, not through formal concepts, but more by the effort invested in the exquisite detailing, precise use of materials, proportions between the elements etc. I’d say that Plečnik is a draughtsman, contrasting Shinohara the mathematician – although sketches played a crucial role in Shinohara’s designs.

IS IT A HOUSE EVERY GRANDMA WOULD LOVE TO LIVE IN?

Yes, of course. I think this has to do with the expression. It is really an architecture that uses architectural elements to directly address your presence. You see a column, you start to talk with the column, you see a sculpture, your eyes interrelate with it. Plečnik was never interested in abstraction, his house is easy to understand, simple to live in. And it’s even homely.

Having said that though, I think the house would still work without decoration and without many of the objects placed within it. It would even work without the classical vocabulary. It’s just cleverly done in terms of proportions, materiality, thresholds, and comfort.

DO YOU THINK THAT THIS ASPECT IS SOMETHING THAT MAKES PLEČNIK A MODERNIST OR IS HE A PART OF A CONSERVATIVE, EVEN SENTIMENTAL TRADITION?

In the case of his house, the attitude of implementing architecture within a certain context and completely remodelling it, is extremely modernistic. If we then look at individual rooms, there is always the relation to outdoor space, again, a very modern preoccupation. But then he used classical forms, classical compositional schemes, traditional elements, the list goes on.

Somehow it is both. He intuitively started to remodel Ljubljana without any direct commission from the city. There were maybe two or three people sitting together drinking a beer or a bottle of wine and discussing issues of faith, the city of Ljubljana and Slovenia’s identity as whole. They worked together on improving and embellishing the city. Plečnik just started designing. He himself, took the responsibility of remodeling of the city. This was a very progressive approach because he was never commissioned by the authorities. He just did it, never asking to be paid.

On the other hand, Plečnik was extremely old-fashioned as a person. He accepted progress and change. But in the end, he was rather reluctant to make them important. I think it boils down to his faith. He really stayed old-fashioned in the way he believed in God. Very similar to Gaudí. Still, at work they both were able to come up with cutting edge ideas.

Plečnik seems to have been reluctant against the modernist dogma of avantgarde with paradoxically the same determination as he was open to shaping his surroundings totally, by newly arranging known forms – which again is very modern in essence.

I cannot precisely trace this to his faith, but the connection to it was extremely productive. With a side look to Gaudí, it seems that the word “creation” – not the “creativity” of our times – might stand at the very epicenter of their will against the world. And creation is related to our times in a more credible way if it is understood as something coming from our very human and natural nature – if you allow for such a tautology. I’m referring here to creation as a concept related to the terrestrial, the earth-bound, as Bruno Latour would say.

IF YOU HAVE TO THINK ABOUT THE HOUSE THAT YOU KNOW AND LIKE VERY MUCH, BUT IN ITS PROPERTIES, ITS FUNDAMENTAL WAY OF BEING CONCEIVED IS OPPOSITE TO PLEČNIK HOUSE, WHAT COMES TO YOUR MIND?

If we look for an opposition, I guess, it should be disconnected from its surroundings. I think this is the main point. An architecture that is only there for architecture - maximally autonomous. And among the houses I know from visiting, then it would be something like Konstantin Melnikov’s own atelier and house in Moscow, a building in splendid isolation between its neighbours from the end of 19th and beginning of 20th century. It’s designed more as an ideal type than for a specific place or context; context doesn’t play any role.

Or, maybe more precise: there is context too, of course: a social context, even a political one of great impact, also a concrete material one – but ex negativo, as if the house directly came from the future.

What is interesting in Plečnik’s house is that it is really a kind of a household. It’s more than a dwelling like Villa Saracena or La Petite Maison of Le Corbusier or Tanikawa house. I will always come back to that - it’s an ecosystem. The architect was living there. He was testing the expression of his style, the elements of his architecture, in and around the house, maybe like Aalto did in his Atelier. Plečnik first started to reshape the surroundings of the house, then he reshaped the surroundings of the garden and the relation to the churchyard. Then, the architect started to work on the relation to the city. This house is both homely and a kind of a node within a much broader network – intimate and public in its very sense.

04.12.2021

蒂伯尔-乔内利:在开始《筱原学(Shinoharistics)》的工作前不久,我曾打算写一篇关于三位建筑师和他们设计的三所住宅的文章。这个系列将是筱原一男、路易吉-莫雷蒂和第三位建筑师。当时,我一直不确定,是否要写乔泽-普莱切尼克(Jože Plečnik)或西格德-卢埃伦茨(Sigurd Lewerentz)。最后我发现,筱原的引力实在是太强了,无法与其他人结合,所以我决定专门写他和谷川家。尽管如此,普莱切尼克仍然是一个非常有趣的主题,有一天,我可以想象写普莱切尼克学(Plečnikistics)。

筱原和乔泽-普莱切尼克有什么共同点?

最明显的是,他们的研究与民族传统产生了强烈的共鸣,从而影响了他们各自国家的认同感。筱原寻找空间的日本性,而普莱切尼克则定义了他的首都卢布尔雅那最重要的公共空间的特征,并谱写了许多取自当时还年轻的斯洛文尼亚的符号。他们之间的另一个重要的相似之处是,他们围绕自己创造了对大师的崇拜,建立了以自己的思想为基础的学派和运动,拥有大量的忠实追随者。然而,除了这些之外,我认为,他们总体上是相当不同的。

普莱切尼克自宅是它所处的周围老住宅系统的一部分,还是它是一个新来者,一个在现有的狭小环境中的入侵者?

嗯,这取决于你指的是哪个版本,例如,第一版设计非常接近于横滨的筱原之家,像一种月球登陆器。它是非常集中的,非常单一的。在后来的版本中,由于一些增加的元素,这个项目变得与周围的环境联系更紧密。我相信这使得房子变得更好。

今天,你通过一条非常狭窄的小巷进入,来到一个院子,两侧是老建筑,正面被普莱切尼克设计的后增的体量所封闭。如果你经过冬季花园,院子会向一大片土地开放。新增的部分,也就是普莱切尼克曾经居住的地方,是面向花园的,与教堂的小园相邻。这是对情况的第一个非常基本的解读。

故事是这样的,他为自己、他的兄弟和姐妹买了这块地。不幸的是,他们的同居生活并没有真正实现,因为建筑师非常敏感,不能被打扰。虽然他依赖于他人的在场和工作,但普莱切尼克真正需要的是一种集中的、隐蔽的生活,以便工作和思考。

住宅本身反映了这种矛盾的情况。它融入了文脉整合——在形式和功能上熔接了新旧,以及有抱负的自主性——为一个特定的个体建造一个空间,考虑到许多私人的兴趣和偏好。

这座住宅不仅与它周围的环境关联,它还与更广泛的城市相联接。卢布尔雅那那些美丽的地方,沿着卢布尔雅那河的整个长廊、图书馆等都是在这所住宅中构思的,住宅本身也成为建筑片段的实验场。

一旦设计完成,一些元件就会被实体模拟出来,并放置在花园里,以检查它们的外观和效用。普莱切尼克还经常保留他城市项目的模型,把它们展示在楼梯和楼上的休息室里。通过这些模型,城市在住宅中富于存在感。他还痴迷于收集古董,往往与自身的经历相关。这些影响反过来又传遍了卢布尔雅那。普莱切尼克确实在住宅和城市之间,在现在和过去之间建立了一种新陈代谢。

这所住宅是否是文化地震的震中,撼动了整座城市?

它有这样一种特质,虽然我对卢布尔雅那和斯洛文尼亚当时经历的文化转型了解不多。但在这种情况下,这所住宅必然成为了一种媒介,通过这种媒介,文化转型的势头越来越大。

虽然是一个内向的人,但最终,普莱切尼克的个人兴趣变得极其公开——反之亦然,城市在住宅中变得有存在感。正是由于这个原因,这所住宅对我来说,依然很有趣。这所住宅同时既是独特的,又与完全多样的文脉进行了对话。

普莱切尼克有意识地将自己与街道的公共性隔绝开来,并决定住在花园里,与相邻的教堂院子建立亲密的关系。以前,花园是普通的、实用的,就像人们在东部随处可见的旧村庄或小布尔乔维亚住宅的院子里一样。花园用于种植食物或饲养动物,它是一种基本资源。但普莱切尼克完全改变了它的意义,使院子和现有的住宅都变得高贵起来。

这种态度在住宅边上的花园中得到了很好的体现,它散发着古典主义城堡般的姿态,并创造了一个奇怪的二分法——既是一个非常封闭的世界,只为自己所知,同时,通过建筑师对城市生活的承诺,向一个更广泛的背景开放。有趣的是,花园仍然被用来种植植物,欢迎邻居们为自己的目的进行栽培。

值得一提的是,当时通往普莱切尼克家的主要通道是沿着教堂院子的边界走的,而不是从街上穿过老房子。他的客人、学生和客户不得不象征性地穿过教堂的领域,进入建筑师的住宅。在那里,他们不得不在长廊上等待,有时要等上几个小时,直到他来到门口迎接他们。我认为,这是用一种很建筑学的方式来上演日常生活——非常戏剧化。作为一个年轻的学生,这就是它吸引我的地方。你需要被迫练习一种仪式,才能真的在住宅中走动,这种仪式是由建筑布局来编排的。我感到一种强烈的牵引力——就像一道牵引光束——指向这样一种宗教承诺,尽管我认为自己是无神论者(我甚至没有接受洗礼)。

你说的 "仪式 "是指什么?

仪式在现代主义之前的所有古典文化中无所不在。普莱切尼克深深地扎根于其中,并理解仪式在其建筑排序中的潜力。

例如,入口处的长廊远不止是一个入口。就像进入卫城,你有一种卫城山门的感觉,进入成为一种游行。卫城山门是普莱切尼克几乎到处使用的一个主题,以区分他所建立的现实和周围的一切。它引入了一种悬念,一种紧张,并设置了一个庄严的过渡场所。

在他画的几乎每一栋建筑中,你都会看到巨大的、沉重的、黑色的柱子和一条神圣的道路,它们既是框架,又引导你进入方案。

你认为主房间为什么是圆形的?

这肯定是参考了巴洛克式城堡中的主厅,向花园突出。与三个窗户一起,圆形创造了强烈的对称性和强烈的指向外部的轴线。而且在上面,一个有着长方形屋顶的住宅,让人联想到一个具有奇怪比例的自立的柱子......一个对柱子着迷的建筑师自己居住在一个柱子内——多么惊人又诙谐的形象啊!

圆形也是一种非常集中的形式。他用它来探索不同活动之间的密切联系。这很有趣,因为即使你的野心是将你的生活完全溶解在一门学科中,或将自己完全奉献给某件事情,身体需求和创作过程的对立仍然存在。普莱切尼克把他的整个生命,他的整个创造力集中在这一个空间中。我想,这就是为什么他引入了一根重梁,放在门框上方。象征性地,它把休息空间和工作空间分开。

我想到的另一个原因是更加正式的。他受到高级意大利建筑和卢布尔雅那及其周边地区更原始的农民建筑的强烈影响。他旅行并访问了许多当地的村庄。圆柱体可以被看作是城堡的塔楼,是那个地区的典型。我想,这也与精神信仰有关。信仰的堡垒在普莱切尼克时代是一个流行的隐喻。

我发现两个完全相反的空间之间的对比很有趣。即,中心的圆形房间,一个工作和睡眠的地方,与长廊的结合——一个长方形的完全装了玻璃和拉长的空间。

建筑史上的中心空间通常意味着是一个空间崇拜,对神性的奉献,完美。不那么对称、不那么集中的几何形状往往更多地暴露在大自然或城市中,以一种不那么仪式化、更轻松的方式工作。在这里,两种类型的房间是沿着一条直线连接的,你可以很快地从一种房间切换到另一种。

普莱切尼克认为,住宅应该始终按照教堂的设计原则来建造。这意味着,他的住宅的主要建筑形式旨在塑造一个神圣的空间。它不是指向性的,它甚至不是一个可以在一起的空间。它具有圆的绝对形式,这给予它自主性,因而使得它类似于教堂的空间。古典的设计方法告诉我们,它需要通过其他的,可以说是不太绝对的元素与周围的环境相连接,在我看来,这使得住宅从构图的角度来看非常有趣。你有主要的空间和周围的环境,保持着一定的距离,或通过一系列的中间空间过渡。

这些外部空间把房子和它的环境联系起来,就像一个锚。它们与入口处的小路、教堂、花园和充满试验性实体模型的场地建立起了密切的关系。它们使房子成为一种生态系统。这座房子并没有真正地分成几个部分,所有的东西都是融合在一起的,但你仍然可以读懂各个元素。它们保持着自己的实质,和自己的特性,就像一个有机体的器官,每一个都发挥着支持性的作用。

筱原也致力于将矛盾的空间特征结合在一起,强调对比和突然的变化,普莱切尼克,正如我们现在所看到的,也结合了完全不同特征的空间,但用更大的努力来实现和谐,一种事物之间的休止状态。

筱原也区分了 "象征性 "和 "功能性 "空间。但他在概念上的明确性,使他与普莱切尼克区分开来。我想这是一个品味或个性的问题。筱原是一种很 "寿司 "的人。在寿司中,你让一切保持原样,把鱼和米饭结合起来,没有任何中介元素,没有酱汁。酱油是事后添加的,当你逐一夹起寿司去浸泡的时候。

就个人而言,我认为普莱切尼克是完全不同的。他寻找的是一个整体艺术作品(Gesamtkunstwerk),一个构思和组成到最终细节的建筑,而且是无缝连接的,全部依赖于传统和象征的关系。筱原依靠的是矛盾、裂隙等概念。

要了解普莱切尼克的设计方式,他家一楼的接待室很重要。只有非常亲密的朋友被邀请到那里——建筑师似乎是非常有选择性的。其他人不得不等待。接待室有一种特殊的不同于住宅其他地方的氛围。然而它被嵌入到整体的设计概念中。我想说,这些空间之间没有强烈的对比,体验它们的过程是流畅的,因为它们是由一个建筑师的手塑造出来的。而 "手 "这个词在这里是至关重要的。对于筱原来说,它更多的是概念性的,我想说的是,它更多的是关于头脑和智力,而更少的是关于工艺或绘画。对于筱原来说,他总是在寻找对立面、分裂、差异,就像住宅在做数学题一样。

在普莱切尼克身上,他的举动背后有一种精神理念,将所有的东西凝聚在一起,当然,这是在宗教中嵌入的,与他所来自的分离派整体艺术(Secession Gesamtkunstwerk)的理念有关。这座建筑慢慢地获得了它的完整性,不是通过形式上的概念,而是更多地通过在精致的细节设计、材料的精确使用、元素之间的比例等方面投入的努力。我想说普莱切尼克是一个绘图员,对比与筱原像个数学家——尽管草图在筱原的设计中起着至关重要的作用。

这是每一位祖母都喜欢住的房子吗?

是的,当然了。我认为这与表达方式有关。这确实是一个使用建筑元素直接定位你的存在的建筑物。你看到一根柱子,你开始与柱子交谈,你看到一尊雕塑,你的眼睛与它相互关联。普莱切尼克对抽象的东西从来不感兴趣,他的房子很容易理解,很简单就能住进去。而且它甚至是家庭式的。

尽管如此,我认为这所住宅在没有装饰,没有那么多放在其中的物品的情况下,仍然可以运作。它甚至在没有古典语汇的情况下也可以成立。它只是在比例、材料、界限和舒适度方面做得很巧妙。

你认为这一方面是使普莱切尼克成为现代主义者的原因,还是他是一个保守的、甚至是感性的传统的一部分?

就他的自宅而言,在一定的文脉下落实建筑,并完全重塑它,这种态度是非常现代的。如果我们再看一下各个房间,总是有着与室外空间的关系,这也是一个非常现代的关注点。但他又使用了古典的形式、古典的构成模式、传统的元素,不一而足。

某种程度上兼而有之。他凭直觉开始改造卢布尔雅那,没有得到城市的任何直接委托。也许有两三个人坐在一起,喝着一瓶啤酒或葡萄酒,讨论信仰问题、卢布尔雅那市和斯洛文尼亚的整体身份。他们一起努力改善和美化这座城市。普莱切尼克就这样开始设计。他自己承担了改造城市的责任。这是一种非常进步的方法,因为他从来没有受到当局的委托。他只是做了这件事,从未要求得到报酬。

另一方面,普莱切尼克作为一个人是极其守旧的。他接受进步和变化。但最终,他相当不情愿让这些事变得重要。我认为这可以归结为他的信仰。他在信仰上帝的方式上确实保持了老派的风格。与高迪非常相似。尽管如此,在工作中,他们都能提出最前沿的想法。

普莱切尼克似乎抗拒现代主义的前卫教义,但矛盾的是,通过重新安排已知的形式,他对塑造他的环境持完全开放的态度——这在本质上又是非常现代的。

我不能准确地把这一点追溯到他的信仰上,但与信仰的联系是极具生产力的。从侧面看高迪,似乎 "创造 "这个词——而不是我们这个时代的 "创造"——可能就站在他们对抗世界的意志的中心。如果创造被理解为来自我们人类和自然本性的东西——如果你允许这样的赘诉——那么创造与我们的时代有更可信的联系。我在这里指的是创造作为一个与陆地有关的概念,地球表面的,正如布鲁诺-拉图尔所说的。

如果你必须想起一个你了解且非常喜欢的住宅,但以其属性来看,它的基本构思方式与普莱切尼克自宅相反,你会想到什么?

如果我们寻找一个对照,我想,它应该与周围的环境脱节。我想这是最主要的一点。一个只为建筑而存在的建筑--最大限度地自主。在我所知道的访问的房子中,那么它将是像康斯坦丁客梅利尼科夫(Konstantin Melnikov)在莫斯科的工作室和自宅,一个在19世纪末和20世纪初的邻居之间的华丽隔绝的建筑。它的设计更多的是作为一种理想的类型,而不是为一个特定的地点或文脉;文脉不发挥任何作用。

或者,也许更准确地说,当然也有文脉:一个社会文脉,甚至一个有巨大影响的政治文脉,也是一个具体的物质背景——但从否定的方面(ex negativo),仿佛房子直接来自未来。

普莱切尼克的房子的有趣之处在于,它确实是一种家庭住宅。它超出于像萨拉切纳住宅或勒-柯布西耶的母亲住宅,或谷川之家那样的住宅。我将永远回到这一点——它是一个生态系统。建筑师在那里生活。他测试他的风格的表达,他的建筑元素,在住宅里和周围环境中,也许就像阿尔托在他的工作室所做的。普莱切尼克首先开始重塑房子的周围,然后他重塑花园的周围和与教堂院子的关系。然后,建筑师开始着手处理与城市的关系。这座房子既是家庭式的,又是一个更广泛的网络中的一个节点--从其本身的意义上来说,是亲密的,也是公共的。

2021年12月04日

ティボール・ヨアネリー:「Shinoharistics」の執筆を始める直前までは、3人の建築家と彼らの設計した3つの住宅についてのエッセイを書くつもりでいました。篠原一男、ルイジ・モレッティ、そしてもう一人です。ヨジェ・プレチニックか、シーグルド・レヴェレンツで迷っていたのです。結局、他の建築家たちと一緒にするには篠原の引力が強すぎて、彼と「谷川さんの住宅」だけに特化して執筆することにしたのです。ただ、プレチニックが非常に面白い対象であることには変わりなく、いつか「Plečnikistics」を書ける日を待ち望んでいました。

篠原一男とプレチニックの共通点はどんなところでしょうか?

最もわかりやすいのは、彼らの探求が母国の伝統と共鳴するもので、それが結果的に国のアイデンティティへと影響を及ぼしている、ということですね。篠原は、空間における日本らしさを追求していました。一方、プレチニックは首都リュブリャナの最も重要な公共空間を特徴づけました。それらは、当時まだ成熟していなかったスロベニアにおいて多くのシンボルとなったのです。もう一つの重要な共通点は、カルト的性質です。独自のスクールが形成され、多くの熱心な信者とともに彼らの思想に基づいた活動が行われていました。ただ、これらの事を除いて俯瞰して見れば、彼らは随分と異なるとは思いますが。

プレチニックの家は、周囲の古い家々の形成するシステムの一部になっているのでしょうか?それとも、緊密に編み込まれた既存の文脈に侵入する新参者といった感じなのでしょうか?

そうですね。どの時期のものかによるのですが、例えば、最初のデザインは篠原の「ハウスインヨコハマ」にとても似ています。月面に着陸してきたみたいですね。非常に集中的で特異なものです。その後、いくつかの要素が追加され、周辺環境と関係を持つようになりました。そのおかげで随分良くなったと思います。

現在のアクセス動線では、細い路地を入ってから中庭に到達します。中庭は古い建物に囲まれていて、増築されたボリュームの正面が近くに見えてきます。冬の庭を通り過ぎると、中庭が広大な土地に向かって開いていることに気づきます。プレチニックの住んでいた増築部分は、教会の敷地に隣接する庭へと向かって方向づけられているのです。以上が最初の、ごく基本的な状況の解読です。

プレチニックは自分自身、そして兄弟のために敷地を買ったらしいのですが、残念ながら共同生活は叶いませんでした。当の建築家があまりにも繊細で、邪魔されることに耐えられなかったからです。彼は、他人の存在や共同作業を頼りにしながらも、仕事や考えに集中できる人里離れた生活を必要としたのです。

この家自体が、その逆説的な状況を反映しています。文脈的統合 - 古いものと新しいものを形式的に、そして機能的に融合すること- と、野心的自律性 - 個人的な趣向や好みによって超特定の個人のために空間を構築すること- とが一体となっているのです。

この家は単に周囲との関係を持つだけでなく、より広域な都市とも関係をもっているのです。リュブリャナの美しい街並み、リュブリャニツァ川につながるプロムナード、そして図書館などは、全てこの家の中で構想されました。この家自体が建築的断片の実験場となっていたわけです。

デザインを考えては、モックアップを作って庭に置き、うまくいっているかどうか見え方を確認していました。プレチニックは、都市計画の模型を保管し、家の階段や二階の製図室に飾っていました。それらの模型を通して、家の中にはまさに都市が立ち現れていたのです。それに彼はアンティークを集めることに夢中でした。その多くは彼の経験と関係のあるものでした。これらの影響が、次々にリュブリャナ全体へ広がっていったのです。プレチニックは、まさに家と都市、現在と過去との間に、ある種の新陳代謝を起こしたのです。

この家が、都市全体を揺るがす文化的な震源地となっていたということでしょうか?

そんな感じだったのでしょうね。当時のリュブリャナやスロヴェニアで起こっていた文化的な変化についてはあまり詳しくないのですが。この家が、その変化を加速させる媒介となっていたことは確かだと思います。

一個人でありながら、プレチニックの私的な関心が極めて公的なものへとなっていき、その逆に、都市が彼の家の中へと現れてくるようになってきた。それが、私がとりわけこの家を興味深く思う理由ですね。ユニークなものでありながら、実に多様な文脈との対話の中でこの家は存在しているということです。

プレチニックは、通りの公共性から意識的に離れて、庭に向かって住むことを決めました。隣接する教会との親密な関係があったからです。以前の庭は、ごく普通の実用的なもので、東の方ではどこにでもあるものでした。古い村の敷地やちょっとしたブルジョア階級の家にあるようなものです。庭は、食料を育てたり、動物を飼ったりするためのもので、必要不可欠な資源でした。プレチニックは、庭と既存の家を高貴に仕立てて、庭の意味をガラッと変えたのです。

その態度は、古典主義的な城のような佇まいをした庭によく現れています。その態度が、奇妙な二分法をも作り出しているわけですが。つまり、自分自身のための非常に閉じられた世界がそこに作られている一方、そこに住む建築家は都市に参与し、より広い文脈へと開かれている、という態度です。興味深いことに、この庭には今でも植物が植えられていて、隣人が好きに栽培できるようになっています。

家に至るまでのアクセスについては、言及する必要がありますね。当時は、大通りから古い家を通り抜けていく方法ではなく、教会の庭に沿った道から家へとアクセスしていたのです。お客さんや学生、それにクライアントまでもが建築家の家へ行くために、教会の領域を象徴的にも横断しなくてはいけませんでした。そして、ベランダでときには何時間もの間、待ち続けるのです。ドアが開き、建築家が出迎えてくれる時を。日常生活を舞台化する、非常に建築的なアプローチですね。とても演劇的です。若い学生であった私は、そこに魅了されてしまいました。家の周りを自由に歩くことはできないのです。建築的な配置が、ある種の強制的な儀式を作り、そこであなたは振り付けを演じるように動くわけです。強力な引力を感じました。トラクタービームのように。宗教的な参与への引力です。私自身は、無神論者だと思っているのですが。(洗礼も受けてませんから。)

儀式という言葉は、具体的には何を指しているのでしょうか?

モダニズム以前には、あらゆる古典的な文化の中に偏在していたものです。プレチニックの感性は、それらに深く根付いていましたし、彼は建築のシークエンスにおける儀式的な可能性を理解していたのです。

例えば、入り口のベランダは単なる入り口ではなく、アクロポリスへ入るときのプロピュライア的な役割が与えられていて、入るという行為が儀式への参列へと変化するのです。プロピュライアは、彼の作り上げたリアリティと、その周囲のもの全てとを区別するために、いつも使われていた手法です。サスペンスと緊張感がもたらされ、移行のための神聖な場所が整えられるのです。

彼の考えたほとんどの建物には、大きく、重く、そして黒い柱と、神聖な通り道が作られています。それらはフレームであると同時に彼の計画の中へとあなたを誘うものなのです。

メインルームが円形なのは、なぜだとお考えですか?

バロックの城のメインホールが、庭へ向かって突き出ているのを参考にしていることは確かだと思います。三つの窓と円形が非常に強いシンメトリーを作り出し、外へ向かって強い軸性を生み出しています。さらには、その上に長方形の屋根が被さっているので、奇妙なプロポーションをした独立柱のようにも思えますし...柱に取り憑かれた建築家が柱の中に棲みつく。なんて印象的でウィットに富んだイメージなのでしょう !

円形は非常に集中的な形でもあるわけですが、彼は、そこに多様な活動をつなぎ合わせる接点を探っていったのです。面白いですよね。あることに人生の全てを費やしたり、打ち込んだりしたくても、身体やそこへ至る過程には無理が生じてしまうのが普通ですから。プレチニックは彼の全人生、そしてある限りの創造性をこの一つの空間へと集中させたのです。想像するに、ドアの枠の上に重い梁が取り付けられているのもそのためでしょう。その梁が休むための空間と働くための空間とを象徴的に分けているのです。

もう一つ考えられる理由は、もっと形式的なものです。つまり彼は、イタリアの格式高い建築とリュブリャナやその周辺の粗末で農村的な建築のどちらにも強く影響を受けていました。彼は地方の村をたくさん訪れていました。ですから、このシリンダー状の形は、それらの地方の典型的な城の搭から来ていると考えることもできますね。おそらくスピリチュアルな事とも関係するのでしょう。信仰の砦という言葉は、プレチニックの時代によく使われたメタファーでもあるのです。

全く正反対な二つの空間のコントラストが興味深いのですが、どうお考えですか。つまり、仕事と睡眠のための中央の円形の部屋と、ガラス張りの細長い長方形のベランダの二つの空間の関係についてどうお考えかお聞かせください。

建築の歴史において中心的な空間というのは、通常、神への献身や完璧性を意味しますよね。一方、対称性や集中性のない幾何学というものは、自然や都市に現れてくるものですし、儀式性のない、もっとリラックスした形で機能するものです。この家においては、二種類のタイプの部屋が一直線上に繋がっていて、一方からもう一方へと簡単に移動することができるようになっています。

プレチニックは、家は教会と同じ設計原理で建てられるべきだと考えていました。そう、彼の家の主な建築的形態は、神聖な空間を意味しているものです。方向づけられているものでもなく、誰かと一緒にいるための空間でもない。円という絶対的な形が、空間に自律性を与え、それゆえに教会の空間と似てくるわけですね。古典的な設計の考え方からすると、家というものは、もっと他の要素、いわば絶対的でない要素によって、周囲と繋がりを持つ必要があると考えるべきなのです。だから、構成的にこの家を考えると、とても面白い。メインスペースと周辺環境とは、一定の距離を保っていますよね。あるいは、中間的な空間によってフィルターがかけられているという感じでしょうか。

これらの外部空間がアンカーとなり、家を周辺の文脈の中に結びつけているのです。玄関への小道、教会、庭、そして実験用モックアップで溢れた畑との密接な関係を作り出しているのです。これらが家をある種のエコシステムへと組み込んでいるわけです。家は要素ごとに分解されてしまうものではなく、全てが融合しつつも、個々の要素が認識され得る状態にあるのです。つまり、それぞれの実体や性質が保持されながらも、有機体である臓器のようにそれぞれが支え合って役割を担っているのです。

篠原も相反する空間をつなぎあわせて、コントラストや突然の変化を強調する操作をしていたと思います。一方、プレチニックには、根本的に異なる性格の空間を組み合わせながらも、調和や安らぎを作り出そうとする努力が感じられるのですが、どう思われますか?

篠原も象徴空間と機能空間とを区別していますね。しかし、コンセプトの明確さにおいては、プレチニックとはかなり異なります。趣味や性格の問題だと思うのですが。篠原はとても「Sushi」的な人なのでしょう。寿司では全てがあるがままという感じですよね。魚と米とをくっつけるのですが、それらを媒介する要素は何もないわけです。ソースもありません。醤油は、一貫ずつ後からつけるものですしね。

個人的には、プレチニックは全くそういう人ではないと思うのです。彼はGesamtkunstwerk(総合芸術)を求めていました。伝統と象徴との関係に依拠しながらも、細部まで構想しつくし、構成されたシームレスで一貫性のある建築を求めたのです。篠原は、矛盾や亀裂などの概念に依拠していたと思いますが。

プレチニックの設計方法を理解するには、一階の応接室が重要です。ごく限られた親しい友人だけが招かれた場所です。建築家は、かなり人を選別していたようですね。他の人は、ただ待たされたのです。この応接室は、他とは異なる特別な雰囲気のものでした。それでも、この部屋はしっかりと全体的なデザインコンセプトの中に組み込まれているのです。空間同士の間に強いコントラストを感じずに流動的な体験ができるのは、おそらく一人の建築家の手によって作りこまれているからなのでしょう。重要なのは「手」という言葉です。篠原の場合は、もっとコンセプチュアルでしょう。クラフト性やドローイングというよりは、心や知性に訴えかけようとするものです。彼は、家が数学をするかのように、対立や分割、そして差異を求めるのでしょう。

プレチニックの場合は、背景の精神的なアイデアが全てを統一しているのです。もちろんそこには宗教や、彼の出自としての分離派のGesamtkunstwerk(総合芸術)のアイデアが関係しています。建物は形式的な概念ではなく、精巧なディテール、精緻な素材の利用、そして要素同士の均衡関係、などに労力がかけられることで、少しずつ統合性を獲得していくものなのです。つまりプレチニックはドラフトマンなのです。篠原が数学者であるのとは対照的ですね。まあ、篠原のデザインにもスケッチは重要な役割を果たしているのですが。

この家は、おばあちゃんでも住みたいと思えるものでしょうか?

ええ、もちろん。それは建築の表現とも関係していると思います。建築的な要素があなたにダイレクトに訴えかける、そんな建築なのです。柱を見れば、あなたは柱と対話を始めますし、彫刻を見れば、あなたの視線と彫刻とが絡み合うのです。プレチニックは抽象化することに全く興味がなかった。彼の家は理解しやすいですし、単純に住みやすい。家庭的でさえある。

とはいえ、装飾や中のオブジェがなくてもこの家は成立すると思うのです。古典的なボキャブラリーがなくなっても問題ないでしょう。プロポーション、素材、境界の作り方、それに心地よさの点において、非常にうまくできています。

こういった点がプレチニックをモダニストたらしめているのでしょうか?それともまだ彼は、保守的でセンチメンタルな伝統に属していると思われますか?

彼の家の場合、既存の文脈を捉えながら、その姿を完全に作り変えてしまう、そういった建築の遂行態度が極めて現代的なのです。個々の部屋を見ると、どれも外部空間との関係を持っていますよね。これもまた非常に現代的な考えです。ところが、古典的な形態、古典的な構成、そして伝統的な要素は、数えればきりがないほどです。

つまり、どちらでもあるという感じですか。彼は、リュブリャナ市から直接依頼があったわけでもなく本能的に、リュブリャナを作り変える計画を始めているのです。二、三人でビールやワインを飲みながら議論していたのでしょう。信仰や、リュブリャナという都市についてや、スロベニアのアイデンティティ全般についてなどを話し合っていたのです。街をより良く、より美しくするために彼らは共に活動していました。プレチニックはただデザインを進めていきました。そして自ら街を作り変える責任を負ったのです。とても先進的な手法でした。市からの依頼ではなかったわけですから。お金が得られるわけでもなく、ただ進めていったのです。

一方、プレチニックは極めて古臭い人間でした。進歩や変化を受け入れてはいましたが、重要だとは思っていませんでした。それは、彼の信仰が原因だと思います。信仰の仕方もまた非常に古臭いものでしたし、ガウディとよく似ているのです。作品においては、どちらも最先端のアイデアを生み出しているのですが。

プレチニックは、アバンギャルドとしてのモダニズムのドグマに対して消極的であったようです。一方、馴染みのある形態を新しく配列し直すことで、周囲の環境を全く作り変えるといったことにはオープンな考えを持っていました。それは、本質的に非常に現代的なものなのですが。つまり逆説的にも到達点が同じなのです。

このことを、彼の信仰と正確にリンクさせていくことはできませんが、信仰との結びつきがとても生産的なものであったことは確かです。ガウディのことも一緒に考えると、私たちの時代における「クリエイティビティ」とは違う意味での「クリエイション」という言葉が、彼らの世界に対する意思の源であったように思えるのです。そのクリエイションを、人間的で自然な本性に由来するものだと考えるのであれば、それは今でも私たちの時代と確かに関係しているのです。トートロジーを承知の上で、ですが。ここで言及しているクリエイションとは、ブルーノ・ラトゥールが言うような、地上にあり、地球に束縛されたものに関わる概念としてのクリエイションです。

あなたが好きで良く知っている住宅の中で、プレチニックの家とは、性質や根本的な考え方が正反対なものはありますか?

正反対なものを探すとすれば、周囲から隔絶された家を選ぶことになりますし、それが主なポイントとなるでしょうか。建築のためだけに存在する建築。つまり極度に自律的な建築です。行ったことのある中でよく知っているのは、モスクワのコンスタンチン・メルニコフのアトリエ兼住宅ですね。19世紀末から20世紀初頭の周辺環境からは見事に孤立しています。特定の場所や文脈のためというよりは、理想的な型として設計されたものです。つまり文脈とは何の関係もない。

いや、もっと正確に考えると、社会的、政治的、あるいは具体的で、物質的な文脈という意味においては、もちろん文脈的な産物です。でもまあ、否定的に捉えれば、未来から降ってきたような家ということです。

プレチニックの家が興味深いのは、そこが家庭そのものであるからです。ラ・サラチェーナやコルビジェの小さな家、あるいは谷川さんの住宅が持つような住居性を超えたものです。私はいつも立ち返ってこのことについて考えるのですが、つまりそれはエコシステムなのです。建築家はそこに住んでいました。表現のスタイルや建築的エレメントを、家の中や、家の周りで試していたのです。アアルトがアトリエでやっていたようにです。プレチニックは、はじめに家の周囲を作り直し、次に家の庭と教会の庭との関係を作り直しました。そして都市との関係を考え始めたのです。この家は、家庭的なものであると同時に、より広域なネットワークの中での、ある種のノードとして機能しているのです。個人的なものでありながら、真の意味でパブリックなものですから。

2021年12月04日

Tibor Joanelly: Shortly before starting work on Shinoharistics, I had intended to write an essay about three architects and three houses they had designed. The collection was to be Kazuo Shinohara, Luigi Moretti and a third one. At the time, I was never sure, whether to write about Jože Plečnik or Sigurd Lewerentz. In the end I figured out that Shinohara’s gravity was just too strong to combine with others, so I decided to write specifically about him and Tanikawa house. Nevertheless, Plečnik remains a very interesting subject and one day, I can imagine writing Plečnikistics.

WHAT DO KAZUO SHINOHARA AND JOŽE PLEČNIK HAVE IN COMMON?

Most obviously, their research resonated strongly with a national tradition and consequently influenced the sense of identity of each of their respective countries. Shinohara looked for the Japan-ness of space, whereas Plečnik defined the character of the most important public spaces in his capital city, Ljubljana and became the author of many symbols taken up by a then young Slovenia. Another important similarity between their characters is the cult of the master that they created around themselves, establishing schools and movements founded on their own ideas, with significant numbers of devoted followers. However, apart from these things, I think, they were overall rather different.

IS PLECNIK’S HOUSE PART OF THE SURROUNDING SYSTEM OF OLD HOUSES THAT IT IS FOUND AMONGST, OR IS IT A NEWCOMER, AN INTRUDER IN THE EXISTING TIGHT NIT CONTEXT?

Well, that depends which version you refer to, for instance, the first design was very close to Shinohara’s House in Yokohama, a kind of moon lander. It was very centralised, very singular. In the later versions, the project, thanks to some additional elements, became more linked to the surroundings. I believe this made the building much better.

Today, you enter through a very narrow alley and arrive to a courtyard flanked by the old building and closed on the front side by the volume of the later addition, designed by Plečnik. If you pass by the winter garden, the courtyard opens towards a big piece of land. The new part, where Plečnik used to live, is oriented towards the garden, adjacent to the yard of the church. This is the first, very basic reading of the situation.

The story goes, that he bought the plot for himself, his brother and sister. Unfortunately, their cohabitation didn’t really work out because the architect was very sensitive and could not be disturbed. Although he depended on both the presence and work of others, Plečnik really needed a concentrated, secluded life in order to work and think.

The house itself reflects this paradoxical situation. It blends contextual integration - formally and functionally melding the old with the new, and an ambitious autonomy - building a space for a very particular individual, taking into account many personal fascinations and preferences.

The house relates not only to its immediate context. It is also connected to the wider city. Beautiful parts of Ljubljana, the whole promenade following the Ljubljanica, the library etc. were all conceived in this house, and the house itself became a testing ground for architectural fragments. Once designed, elements were mocked up and placed in the garden to check how they looked and if they worked or not. Plečnik also used to keep the models of his projects for the city, displaying them in the staircase and in the drawing room upstairs. Through these models the city became very present within the house. And he obsessively collected antiques, often related to his own experience. These influences were in turn spread all over Ljubljana. Plečnik really established a kind of metabolism between house and city, between present and past.

WAS THE HOUSE THE EPICENTRE OF A CULTURAL EARTHQUAKE, SHAKING THE WHOLE CITY?

It has a quality like that, although I don’t know too much about the cultural transitions that Ljubljana and Slovenia went through at that time. But in this context, the house must have become a kind of medium by which the cultural transformation was gaining momentum.

Although a private man, ultimately, Plečnik’s personal interests became extremely public – and vice versa, the city became present in the house. It is for this reason that the house remains, for me, interesting. At the same time the house is both unique, and in dialogue with completely diverse contexts.

Plečnik consciously cut himself off from the publicness of the street and decided to live towards the garden, in an intimate relationship with the adjacent church yard. Before, the garden was ordinary, utilitarian, as one finds everywhere in the east, in the yards of old villages or petty bourgeois houses. The garden served for growing food or keeping animals, it was an essential resource. But Plečnik completely changed its meaning by ennobling both, the yard, and existing houses.

This attitude is well expressed in the garden at the side of the house which exudes a classicist castle-like attitude and creates a strange dichotomy – at once being a very closed world, known only to itself, whilst, through the architect’s lived commitment towards the city, opening to a much broader context. Interestingly, the garden was still used for growing plants, for which neighbours were welcomed to cultivate for their own purpose.

It’s important to mention, that the main access to Plečnik’s house was, at that time, along a path that follows the border of the church yard and not through the old house from the street. His guests, students and for that matter, clients had to symbolically cross the domain of the church to access the architect’s house. There they had to wait on a veranda, sometimes for hours until he came to the door and greeted them. I think, it’s a very architectonic approach to staging everyday life - very theatrical. As a young student this is what attracted me to it. You cannot really move around the house without practicing a kind of enforced ritual, choreographed by the architectural arrangement. And I feel a strong pull – like a tractor beam – towards such a religious commitment, although I consider myself an atheist (I’m not even baptized).

WHAT DO YOU REFER TO WITH THE WORD RITUAL?

Ritual was omnipresent in all classical cultures before modernism. Plečnik was deeply rooted in them and understood the potential of rituals in the sequencing of his architecture.

For instance, the entrance veranda is much more than just an entrance. It’s like entering the Acropolis, you have a sort of Propylaea, entering becomes a procession. The propylaeum is a topic that Plečnik used almost everywhere to differentiate the reality he built from everything around. It introduced a suspense, a tension and set a solemn place of transition.

In almost every building he drew, you have the large, heavy, black columns and a sacred path that both frame and lead you into the plan.

WHY DO YOU THINK THE MAIN ROOM IS CIRCULAR?

There is surely a reference to the main hall in a baroque castle, projecting towards the garden. Together with the three windows, the circularity creates a very strong symmetry and a very strong axis towards the outside. And, beyond that, the house, with the rectangular roof, reminds a free-standing column with strange proportions… An architect with a fascination for columns himself inhabits a column – what a striking, witty image!

The circular shape is also a very concentrated form. He used it to explore the close connection between different activities. It is interesting, because even if your ambition is to completely dissolve your life in a discipline or dedicate yourself completely to something, the opposition of bodily needs and the creative process remains. Plečnik concentrated his whole life, his whole creativity within this one space. I assume, that’s why he introduced a heavy beam, resting above the door frames. Symbolically, it separates the space for rest and the space for work.

Another reason that comes to my mind is more formal. He was strongly influenced by both high Italian architecture and the more rudimentary peasant architecture of Ljubljana and its surroundings. He travelled and visited many local villages. The cylinder could be seen as the tower of a castle, typical of that region. I guess, it also had something to do with spirituality. The stronghold of faith was a popular metaphor in the times of Plečnik.

I FIND THE CONTRAST BETWEEN TWO COMPLETELY OPPOSITE SPACES INTERESTING. NAMELY, THE COMBINATION OF THE CENTRAL CIRCULAR ROOM, A PLACE OF WORK AND SLEEP, WITH THE VERANDA - A RECTANGULAR COMPLETELY GLAZED AND ELONGATED SPACE.

A central space in architectural history was usually meant to be a space of cult, of dedication to divinity, of perfection. Less symmetrical, less concentrated geometries were often more exposed to the nature or to the city, working in a less ceremonial, more relaxed way. Here the two types of rooms are connected along one straight line, you can just switch from one to another very quickly.

Plečnik believed that a house should always be built according to the design principles of a church. It means, that the primary architectural form of his house is meant to be a sacred space. It’s not directed, it’s not even a space to be together. It has the absolute form of the circle, which gives it autonomy, therefore makes it resemble the space of a church. The classical approach to design tells us that it needs to be connected to its surroundings by other, so to speak, less absolute elements, which, in my opinion, makes the house very interesting from the point of view of composition. You have the main space and the surroundings, kept at a distance, or filtered through a series of intermediate spaces.

These external spaces link the house to its context, like an anchor. They establish close relationships to the entrance path, to the church, to the garden, and to the field full of experimental mock-ups. They make the house a kind of ecosystem. The house doesn’t really fall into parts, everything is fused, but you can still read the individual elements. They keep their own substance, and their own character, like organs of an organism where each one plays a supportive role.

SHINOHARA TOO WORKED WITH BRINGING TOGETHER CONTRADICTORY FEATURES OF SPACE, STRESSING THE CONTRASTS AND ABRUPT CHANGES, PLEČNIK, AS WE CAN SEE EVEN NOW, ALSO COMBINED SPACES OF RADICALLY DIFFERENT CHARACTERS, BUT THERE IS A GREATER ENDEAVOUR TO ACHIEVE HARMONY, A STATE OF REST BETWEEN THINGS.

Shinohara also distinguished between “symbolic” and “functional” spaces. But the conceptual clarity with which he did that, separates him from Plečnik. I think it’s a question of taste or personality. Shinohara was a very „sushi” kind of person. In sushi you leave everything as it is, you combine fish with rice without any mediating element, without sauce. Soy sauce is added afterwards when you pick the Sushi piece by piece and dip it.

Personally, I think Plečnik was completely different. He searched for a Gesamtkunstwerk, for a building conceived and composed to the last detail and seamlessly coherent, all relying on tradition and symbolic relations. Shinohara relied on concepts of contradiction, fissure etc.

To understand the way how Plečnik was designing, the reception room on the first floor of his house is important. Only very close friends were invited there – the architect seems to have been very selective. Others had to wait. The reception room had a special and different atmosphere than the rest of the house. However, it was embedded within a total design concept. I would say, there are no strong contrasts between the spaces, experiencing them happens fluidly because they are so much shaped by one architect’s hand. And the word „hand” is crucial here. With Shinohara, it’s much more conceptual, I would say, it’s more about mind and intellect and much less about craft or drawing. With Shinohara, he is always searching for oppositions, divisions, differences, as if a house was doing mathematics.

In Plečnik there is rather a kind of spiritual idea behind his moves, that holds everything together, which is, of course, embedded in religion and related to the idea of Secession Gesamtkunstwerk, where he comes from. The building slowly acquires its integrity, not through formal concepts, but more by the effort invested in the exquisite detailing, precise use of materials, proportions between the elements etc. I’d say that Plečnik is a draughtsman, contrasting Shinohara the mathematician – although sketches played a crucial role in Shinohara’s designs.

IS IT A HOUSE EVERY GRANDMA WOULD LOVE TO LIVE IN?

Yes, of course. I think this has to do with the expression. It is really an architecture that uses architectural elements to directly address your presence. You see a column, you start to talk with the column, you see a sculpture, your eyes interrelate with it. Plečnik was never interested in abstraction, his house is easy to understand, simple to live in. And it’s even homely.

Having said that though, I think the house would still work without decoration and without many of the objects placed within it. It would even work without the classical vocabulary. It’s just cleverly done in terms of proportions, materiality, thresholds, and comfort.

DO YOU THINK THAT THIS ASPECT IS SOMETHING THAT MAKES PLEČNIK A MODERNIST OR IS HE A PART OF A CONSERVATIVE, EVEN SENTIMENTAL TRADITION?

In the case of his house, the attitude of implementing architecture within a certain context and completely remodelling it, is extremely modernistic. If we then look at individual rooms, there is always the relation to outdoor space, again, a very modern preoccupation. But then he used classical forms, classical compositional schemes, traditional elements, the list goes on.

Somehow it is both. He intuitively started to remodel Ljubljana without any direct commission from the city. There were maybe two or three people sitting together drinking a beer or a bottle of wine and discussing issues of faith, the city of Ljubljana and Slovenia’s identity as whole. They worked together on improving and embellishing the city. Plečnik just started designing. He himself, took the responsibility of remodeling of the city. This was a very progressive approach because he was never commissioned by the authorities. He just did it, never asking to be paid.

On the other hand, Plečnik was extremely old-fashioned as a person. He accepted progress and change. But in the end, he was rather reluctant to make them important. I think it boils down to his faith. He really stayed old-fashioned in the way he believed in God. Very similar to Gaudí. Still, at work they both were able to come up with cutting edge ideas.

Plečnik seems to have been reluctant against the modernist dogma of avantgarde with paradoxically the same determination as he was open to shaping his surroundings totally, by newly arranging known forms – which again is very modern in essence.

I cannot precisely trace this to his faith, but the connection to it was extremely productive. With a side look to Gaudí, it seems that the word “creation” – not the “creativity” of our times – might stand at the very epicenter of their will against the world. And creation is related to our times in a more credible way if it is understood as something coming from our very human and natural nature – if you allow for such a tautology. I’m referring here to creation as a concept related to the terrestrial, the earth-bound, as Bruno Latour would say.

IF YOU HAVE TO THINK ABOUT THE HOUSE THAT YOU KNOW AND LIKE VERY MUCH, BUT IN ITS PROPERTIES, ITS FUNDAMENTAL WAY OF BEING CONCEIVED IS OPPOSITE TO PLEČNIK HOUSE, WHAT COMES TO YOUR MIND?

If we look for an opposition, I guess, it should be disconnected from its surroundings. I think this is the main point. An architecture that is only there for architecture - maximally autonomous. And among the houses I know from visiting, then it would be something like Konstantin Melnikov’s own atelier and house in Moscow, a building in splendid isolation between its neighbours from the end of 19th and beginning of 20th century. It’s designed more as an ideal type than for a specific place or context; context doesn’t play any role.

Or, maybe more precise: there is context too, of course: a social context, even a political one of great impact, also a concrete material one – but ex negativo, as if the house directly came from the future.

What is interesting in Plečnik’s house is that it is really a kind of a household. It’s more than a dwelling like Villa Saracena or La Petite Maison of Le Corbusier or Tanikawa house. I will always come back to that - it’s an ecosystem. The architect was living there. He was testing the expression of his style, the elements of his architecture, in and around the house, maybe like Aalto did in his Atelier. Plečnik first started to reshape the surroundings of the house, then he reshaped the surroundings of the garden and the relation to the churchyard. Then, the architect started to work on the relation to the city. This house is both homely and a kind of a node within a much broader network – intimate and public in its very sense.

04.12.2021

蒂伯尔-乔内利:在开始《筱原学(Shinoharistics)》的工作前不久,我曾打算写一篇关于三位建筑师和他们设计的三所住宅的文章。这个系列将是筱原一男、路易吉-莫雷蒂和第三位建筑师。当时,我一直不确定,是否要写乔泽-普莱切尼克(Jože Plečnik)或西格德-卢埃伦茨(Sigurd Lewerentz)。最后我发现,筱原的引力实在是太强了,无法与其他人结合,所以我决定专门写他和谷川家。尽管如此,普莱切尼克仍然是一个非常有趣的主题,有一天,我可以想象写普莱切尼克学(Plečnikistics)。

筱原和乔泽-普莱切尼克有什么共同点?

最明显的是,他们的研究与民族传统产生了强烈的共鸣,从而影响了他们各自国家的认同感。筱原寻找空间的日本性,而普莱切尼克则定义了他的首都卢布尔雅那最重要的公共空间的特征,并谱写了许多取自当时还年轻的斯洛文尼亚的符号。他们之间的另一个重要的相似之处是,他们围绕自己创造了对大师的崇拜,建立了以自己的思想为基础的学派和运动,拥有大量的忠实追随者。然而,除了这些之外,我认为,他们总体上是相当不同的。

普莱切尼克自宅是它所处的周围老住宅系统的一部分,还是它是一个新来者,一个在现有的狭小环境中的入侵者?

嗯,这取决于你指的是哪个版本,例如,第一版设计非常接近于横滨的筱原之家,像一种月球登陆器。它是非常集中的,非常单一的。在后来的版本中,由于一些增加的元素,这个项目变得与周围的环境联系更紧密。我相信这使得房子变得更好。

今天,你通过一条非常狭窄的小巷进入,来到一个院子,两侧是老建筑,正面被普莱切尼克设计的后增的体量所封闭。如果你经过冬季花园,院子会向一大片土地开放。新增的部分,也就是普莱切尼克曾经居住的地方,是面向花园的,与教堂的小园相邻。这是对情况的第一个非常基本的解读。

故事是这样的,他为自己、他的兄弟和姐妹买了这块地。不幸的是,他们的同居生活并没有真正实现,因为建筑师非常敏感,不能被打扰。虽然他依赖于他人的在场和工作,但普莱切尼克真正需要的是一种集中的、隐蔽的生活,以便工作和思考。

住宅本身反映了这种矛盾的情况。它融入了文脉整合——在形式和功能上熔接了新旧,以及有抱负的自主性——为一个特定的个体建造一个空间,考虑到许多私人的兴趣和偏好。

这座住宅不仅与它周围的环境关联,它还与更广泛的城市相联接。卢布尔雅那那些美丽的地方,沿着卢布尔雅那河的整个长廊、图书馆等都是在这所住宅中构思的,住宅本身也成为建筑片段的实验场。

一旦设计完成,一些元件就会被实体模拟出来,并放置在花园里,以检查它们的外观和效用。普莱切尼克还经常保留他城市项目的模型,把它们展示在楼梯和楼上的休息室里。通过这些模型,城市在住宅中富于存在感。他还痴迷于收集古董,往往与自身的经历相关。这些影响反过来又传遍了卢布尔雅那。普莱切尼克确实在住宅和城市之间,在现在和过去之间建立了一种新陈代谢。

这所住宅是否是文化地震的震中,撼动了整座城市?

它有这样一种特质,虽然我对卢布尔雅那和斯洛文尼亚当时经历的文化转型了解不多。但在这种情况下,这所住宅必然成为了一种媒介,通过这种媒介,文化转型的势头越来越大。

虽然是一个内向的人,但最终,普莱切尼克的个人兴趣变得极其公开——反之亦然,城市在住宅中变得有存在感。正是由于这个原因,这所住宅对我来说,依然很有趣。这所住宅同时既是独特的,又与完全多样的文脉进行了对话。

普莱切尼克有意识地将自己与街道的公共性隔绝开来,并决定住在花园里,与相邻的教堂院子建立亲密的关系。以前,花园是普通的、实用的,就像人们在东部随处可见的旧村庄或小布尔乔维亚住宅的院子里一样。花园用于种植食物或饲养动物,它是一种基本资源。但普莱切尼克完全改变了它的意义,使院子和现有的住宅都变得高贵起来。

这种态度在住宅边上的花园中得到了很好的体现,它散发着古典主义城堡般的姿态,并创造了一个奇怪的二分法——既是一个非常封闭的世界,只为自己所知,同时,通过建筑师对城市生活的承诺,向一个更广泛的背景开放。有趣的是,花园仍然被用来种植植物,欢迎邻居们为自己的目的进行栽培。

值得一提的是,当时通往普莱切尼克家的主要通道是沿着教堂院子的边界走的,而不是从街上穿过老房子。他的客人、学生和客户不得不象征性地穿过教堂的领域,进入建筑师的住宅。在那里,他们不得不在长廊上等待,有时要等上几个小时,直到他来到门口迎接他们。我认为,这是用一种很建筑学的方式来上演日常生活——非常戏剧化。作为一个年轻的学生,这就是它吸引我的地方。你需要被迫练习一种仪式,才能真的在住宅中走动,这种仪式是由建筑布局来编排的。我感到一种强烈的牵引力——就像一道牵引光束——指向这样一种宗教承诺,尽管我认为自己是无神论者(我甚至没有接受洗礼)。

你说的 "仪式 "是指什么?

仪式在现代主义之前的所有古典文化中无所不在。普莱切尼克深深地扎根于其中,并理解仪式在其建筑排序中的潜力。

例如,入口处的长廊远不止是一个入口。就像进入卫城,你有一种卫城山门的感觉,进入成为一种游行。卫城山门是普莱切尼克几乎到处使用的一个主题,以区分他所建立的现实和周围的一切。它引入了一种悬念,一种紧张,并设置了一个庄严的过渡场所。

在他画的几乎每一栋建筑中,你都会看到巨大的、沉重的、黑色的柱子和一条神圣的道路,它们既是框架,又引导你进入方案。

你认为主房间为什么是圆形的?

这肯定是参考了巴洛克式城堡中的主厅,向花园突出。与三个窗户一起,圆形创造了强烈的对称性和强烈的指向外部的轴线。而且在上面,一个有着长方形屋顶的住宅,让人联想到一个具有奇怪比例的自立的柱子......一个对柱子着迷的建筑师自己居住在一个柱子内——多么惊人又诙谐的形象啊!

圆形也是一种非常集中的形式。他用它来探索不同活动之间的密切联系。这很有趣,因为即使你的野心是将你的生活完全溶解在一门学科中,或将自己完全奉献给某件事情,身体需求和创作过程的对立仍然存在。普莱切尼克把他的整个生命,他的整个创造力集中在这一个空间中。我想,这就是为什么他引入了一根重梁,放在门框上方。象征性地,它把休息空间和工作空间分开。

我想到的另一个原因是更加正式的。他受到高级意大利建筑和卢布尔雅那及其周边地区更原始的农民建筑的强烈影响。他旅行并访问了许多当地的村庄。圆柱体可以被看作是城堡的塔楼,是那个地区的典型。我想,这也与精神信仰有关。信仰的堡垒在普莱切尼克时代是一个流行的隐喻。

我发现两个完全相反的空间之间的对比很有趣。即,中心的圆形房间,一个工作和睡眠的地方,与长廊的结合——一个长方形的完全装了玻璃和拉长的空间。

建筑史上的中心空间通常意味着是一个空间崇拜,对神性的奉献,完美。不那么对称、不那么集中的几何形状往往更多地暴露在大自然或城市中,以一种不那么仪式化、更轻松的方式工作。在这里,两种类型的房间是沿着一条直线连接的,你可以很快地从一种房间切换到另一种。

普莱切尼克认为,住宅应该始终按照教堂的设计原则来建造。这意味着,他的住宅的主要建筑形式旨在塑造一个神圣的空间。它不是指向性的,它甚至不是一个可以在一起的空间。它具有圆的绝对形式,这给予它自主性,因而使得它类似于教堂的空间。古典的设计方法告诉我们,它需要通过其他的,可以说是不太绝对的元素与周围的环境相连接,在我看来,这使得住宅从构图的角度来看非常有趣。你有主要的空间和周围的环境,保持着一定的距离,或通过一系列的中间空间过渡。

这些外部空间把房子和它的环境联系起来,就像一个锚。它们与入口处的小路、教堂、花园和充满试验性实体模型的场地建立起了密切的关系。它们使房子成为一种生态系统。这座房子并没有真正地分成几个部分,所有的东西都是融合在一起的,但你仍然可以读懂各个元素。它们保持着自己的实质,和自己的特性,就像一个有机体的器官,每一个都发挥着支持性的作用。

筱原也致力于将矛盾的空间特征结合在一起,强调对比和突然的变化,普莱切尼克,正如我们现在所看到的,也结合了完全不同特征的空间,但用更大的努力来实现和谐,一种事物之间的休止状态。

筱原也区分了 "象征性 "和 "功能性 "空间。但他在概念上的明确性,使他与普莱切尼克区分开来。我想这是一个品味或个性的问题。筱原是一种很 "寿司 "的人。在寿司中,你让一切保持原样,把鱼和米饭结合起来,没有任何中介元素,没有酱汁。酱油是事后添加的,当你逐一夹起寿司去浸泡的时候。

就个人而言,我认为普莱切尼克是完全不同的。他寻找的是一个整体艺术作品(Gesamtkunstwerk),一个构思和组成到最终细节的建筑,而且是无缝连接的,全部依赖于传统和象征的关系。筱原依靠的是矛盾、裂隙等概念。

要了解普莱切尼克的设计方式,他家一楼的接待室很重要。只有非常亲密的朋友被邀请到那里——建筑师似乎是非常有选择性的。其他人不得不等待。接待室有一种特殊的不同于住宅其他地方的氛围。然而它被嵌入到整体的设计概念中。我想说,这些空间之间没有强烈的对比,体验它们的过程是流畅的,因为它们是由一个建筑师的手塑造出来的。而 "手 "这个词在这里是至关重要的。对于筱原来说,它更多的是概念性的,我想说的是,它更多的是关于头脑和智力,而更少的是关于工艺或绘画。对于筱原来说,他总是在寻找对立面、分裂、差异,就像住宅在做数学题一样。

在普莱切尼克身上,他的举动背后有一种精神理念,将所有的东西凝聚在一起,当然,这是在宗教中嵌入的,与他所来自的分离派整体艺术(Secession Gesamtkunstwerk)的理念有关。这座建筑慢慢地获得了它的完整性,不是通过形式上的概念,而是更多地通过在精致的细节设计、材料的精确使用、元素之间的比例等方面投入的努力。我想说普莱切尼克是一个绘图员,对比与筱原像个数学家——尽管草图在筱原的设计中起着至关重要的作用。

这是每一位祖母都喜欢住的房子吗?

是的,当然了。我认为这与表达方式有关。这确实是一个使用建筑元素直接定位你的存在的建筑物。你看到一根柱子,你开始与柱子交谈,你看到一尊雕塑,你的眼睛与它相互关联。普莱切尼克对抽象的东西从来不感兴趣,他的房子很容易理解,很简单就能住进去。而且它甚至是家庭式的。

尽管如此,我认为这所住宅在没有装饰,没有那么多放在其中的物品的情况下,仍然可以运作。它甚至在没有古典语汇的情况下也可以成立。它只是在比例、材料、界限和舒适度方面做得很巧妙。

你认为这一方面是使普莱切尼克成为现代主义者的原因,还是他是一个保守的、甚至是感性的传统的一部分?

就他的自宅而言,在一定的文脉下落实建筑,并完全重塑它,这种态度是非常现代的。如果我们再看一下各个房间,总是有着与室外空间的关系,这也是一个非常现代的关注点。但他又使用了古典的形式、古典的构成模式、传统的元素,不一而足。

某种程度上兼而有之。他凭直觉开始改造卢布尔雅那,没有得到城市的任何直接委托。也许有两三个人坐在一起,喝着一瓶啤酒或葡萄酒,讨论信仰问题、卢布尔雅那市和斯洛文尼亚的整体身份。他们一起努力改善和美化这座城市。普莱切尼克就这样开始设计。他自己承担了改造城市的责任。这是一种非常进步的方法,因为他从来没有受到当局的委托。他只是做了这件事,从未要求得到报酬。

另一方面,普莱切尼克作为一个人是极其守旧的。他接受进步和变化。但最终,他相当不情愿让这些事变得重要。我认为这可以归结为他的信仰。他在信仰上帝的方式上确实保持了老派的风格。与高迪非常相似。尽管如此,在工作中,他们都能提出最前沿的想法。

普莱切尼克似乎抗拒现代主义的前卫教义,但矛盾的是,通过重新安排已知的形式,他对塑造他的环境持完全开放的态度——这在本质上又是非常现代的。

我不能准确地把这一点追溯到他的信仰上,但与信仰的联系是极具生产力的。从侧面看高迪,似乎 "创造 "这个词——而不是我们这个时代的 "创造"——可能就站在他们对抗世界的意志的中心。如果创造被理解为来自我们人类和自然本性的东西——如果你允许这样的赘诉——那么创造与我们的时代有更可信的联系。我在这里指的是创造作为一个与陆地有关的概念,地球表面的,正如布鲁诺-拉图尔所说的。

如果你必须想起一个你了解且非常喜欢的住宅,但以其属性来看,它的基本构思方式与普莱切尼克自宅相反,你会想到什么?

如果我们寻找一个对照,我想,它应该与周围的环境脱节。我想这是最主要的一点。一个只为建筑而存在的建筑--最大限度地自主。在我所知道的访问的房子中,那么它将是像康斯坦丁客梅利尼科夫(Konstantin Melnikov)在莫斯科的工作室和自宅,一个在19世纪末和20世纪初的邻居之间的华丽隔绝的建筑。它的设计更多的是作为一种理想的类型,而不是为一个特定的地点或文脉;文脉不发挥任何作用。

或者,也许更准确地说,当然也有文脉:一个社会文脉,甚至一个有巨大影响的政治文脉,也是一个具体的物质背景——但从否定的方面(ex negativo),仿佛房子直接来自未来。

普莱切尼克的房子的有趣之处在于,它确实是一种家庭住宅。它超出于像萨拉切纳住宅或勒-柯布西耶的母亲住宅,或谷川之家那样的住宅。我将永远回到这一点——它是一个生态系统。建筑师在那里生活。他测试他的风格的表达,他的建筑元素,在住宅里和周围环境中,也许就像阿尔托在他的工作室所做的。普莱切尼克首先开始重塑房子的周围,然后他重塑花园的周围和与教堂院子的关系。然后,建筑师开始着手处理与城市的关系。这座房子既是家庭式的,又是一个更广泛的网络中的一个节点--从其本身的意义上来说,是亲密的,也是公共的。

2021年12月04日

ティボール・ヨアネリー:「Shinoharistics」の執筆を始める直前までは、3人の建築家と彼らの設計した3つの住宅についてのエッセイを書くつもりでいました。篠原一男、ルイジ・モレッティ、そしてもう一人です。ヨジェ・プレチニックか、シーグルド・レヴェレンツで迷っていたのです。結局、他の建築家たちと一緒にするには篠原の引力が強すぎて、彼と「谷川さんの住宅」だけに特化して執筆することにしたのです。ただ、プレチニックが非常に面白い対象であることには変わりなく、いつか「Plečnikistics」を書ける日を待ち望んでいました。

篠原一男とプレチニックの共通点はどんなところでしょうか?

最もわかりやすいのは、彼らの探求が母国の伝統と共鳴するもので、それが結果的に国のアイデンティティへと影響を及ぼしている、ということですね。篠原は、空間における日本らしさを追求していました。一方、プレチニックは首都リュブリャナの最も重要な公共空間を特徴づけました。それらは、当時まだ成熟していなかったスロベニアにおいて多くのシンボルとなったのです。もう一つの重要な共通点は、カルト的性質です。独自のスクールが形成され、多くの熱心な信者とともに彼らの思想に基づいた活動が行われていました。ただ、これらの事を除いて俯瞰して見れば、彼らは随分と異なるとは思いますが。

プレチニックの家は、周囲の古い家々の形成するシステムの一部になっているのでしょうか?それとも、緊密に編み込まれた既存の文脈に侵入する新参者といった感じなのでしょうか?

そうですね。どの時期のものかによるのですが、例えば、最初のデザインは篠原の「ハウスインヨコハマ」にとても似ています。月面に着陸してきたみたいですね。非常に集中的で特異なものです。その後、いくつかの要素が追加され、周辺環境と関係を持つようになりました。そのおかげで随分良くなったと思います。

現在のアクセス動線では、細い路地を入ってから中庭に到達します。中庭は古い建物に囲まれていて、増築されたボリュームの正面が近くに見えてきます。冬の庭を通り過ぎると、中庭が広大な土地に向かって開いていることに気づきます。プレチニックの住んでいた増築部分は、教会の敷地に隣接する庭へと向かって方向づけられているのです。以上が最初の、ごく基本的な状況の解読です。

プレチニックは自分自身、そして兄弟のために敷地を買ったらしいのですが、残念ながら共同生活は叶いませんでした。当の建築家があまりにも繊細で、邪魔されることに耐えられなかったからです。彼は、他人の存在や共同作業を頼りにしながらも、仕事や考えに集中できる人里離れた生活を必要としたのです。

この家自体が、その逆説的な状況を反映しています。文脈的統合 - 古いものと新しいものを形式的に、そして機能的に融合すること- と、野心的自律性 - 個人的な趣向や好みによって超特定の個人のために空間を構築すること- とが一体となっているのです。

この家は単に周囲との関係を持つだけでなく、より広域な都市とも関係をもっているのです。リュブリャナの美しい街並み、リュブリャニツァ川につながるプロムナード、そして図書館などは、全てこの家の中で構想されました。この家自体が建築的断片の実験場となっていたわけです。

デザインを考えては、モックアップを作って庭に置き、うまくいっているかどうか見え方を確認していました。プレチニックは、都市計画の模型を保管し、家の階段や二階の製図室に飾っていました。それらの模型を通して、家の中にはまさに都市が立ち現れていたのです。それに彼はアンティークを集めることに夢中でした。その多くは彼の経験と関係のあるものでした。これらの影響が、次々にリュブリャナ全体へ広がっていったのです。プレチニックは、まさに家と都市、現在と過去との間に、ある種の新陳代謝を起こしたのです。

この家が、都市全体を揺るがす文化的な震源地となっていたということでしょうか?

そんな感じだったのでしょうね。当時のリュブリャナやスロヴェニアで起こっていた文化的な変化についてはあまり詳しくないのですが。この家が、その変化を加速させる媒介となっていたことは確かだと思います。

一個人でありながら、プレチニックの私的な関心が極めて公的なものへとなっていき、その逆に、都市が彼の家の中へと現れてくるようになってきた。それが、私がとりわけこの家を興味深く思う理由ですね。ユニークなものでありながら、実に多様な文脈との対話の中でこの家は存在しているということです。

プレチニックは、通りの公共性から意識的に離れて、庭に向かって住むことを決めました。隣接する教会との親密な関係があったからです。以前の庭は、ごく普通の実用的なもので、東の方ではどこにでもあるものでした。古い村の敷地やちょっとしたブルジョア階級の家にあるようなものです。庭は、食料を育てたり、動物を飼ったりするためのもので、必要不可欠な資源でした。プレチニックは、庭と既存の家を高貴に仕立てて、庭の意味をガラッと変えたのです。

その態度は、古典主義的な城のような佇まいをした庭によく現れています。その態度が、奇妙な二分法をも作り出しているわけですが。つまり、自分自身のための非常に閉じられた世界がそこに作られている一方、そこに住む建築家は都市に参与し、より広い文脈へと開かれている、という態度です。興味深いことに、この庭には今でも植物が植えられていて、隣人が好きに栽培できるようになっています。

家に至るまでのアクセスについては、言及する必要がありますね。当時は、大通りから古い家を通り抜けていく方法ではなく、教会の庭に沿った道から家へとアクセスしていたのです。お客さんや学生、それにクライアントまでもが建築家の家へ行くために、教会の領域を象徴的にも横断しなくてはいけませんでした。そして、ベランダでときには何時間もの間、待ち続けるのです。ドアが開き、建築家が出迎えてくれる時を。日常生活を舞台化する、非常に建築的なアプローチですね。とても演劇的です。若い学生であった私は、そこに魅了されてしまいました。家の周りを自由に歩くことはできないのです。建築的な配置が、ある種の強制的な儀式を作り、そこであなたは振り付けを演じるように動くわけです。強力な引力を感じました。トラクタービームのように。宗教的な参与への引力です。私自身は、無神論者だと思っているのですが。(洗礼も受けてませんから。)

儀式という言葉は、具体的には何を指しているのでしょうか?

モダニズム以前には、あらゆる古典的な文化の中に偏在していたものです。プレチニックの感性は、それらに深く根付いていましたし、彼は建築のシークエンスにおける儀式的な可能性を理解していたのです。

例えば、入り口のベランダは単なる入り口ではなく、アクロポリスへ入るときのプロピュライア的な役割が与えられていて、入るという行為が儀式への参列へと変化するのです。プロピュライアは、彼の作り上げたリアリティと、その周囲のもの全てとを区別するために、いつも使われていた手法です。サスペンスと緊張感がもたらされ、移行のための神聖な場所が整えられるのです。

彼の考えたほとんどの建物には、大きく、重く、そして黒い柱と、神聖な通り道が作られています。それらはフレームであると同時に彼の計画の中へとあなたを誘うものなのです。

メインルームが円形なのは、なぜだとお考えですか?

バロックの城のメインホールが、庭へ向かって突き出ているのを参考にしていることは確かだと思います。三つの窓と円形が非常に強いシンメトリーを作り出し、外へ向かって強い軸性を生み出しています。さらには、その上に長方形の屋根が被さっているので、奇妙なプロポーションをした独立柱のようにも思えますし...柱に取り憑かれた建築家が柱の中に棲みつく。なんて印象的でウィットに富んだイメージなのでしょう !

円形は非常に集中的な形でもあるわけですが、彼は、そこに多様な活動をつなぎ合わせる接点を探っていったのです。面白いですよね。あることに人生の全てを費やしたり、打ち込んだりしたくても、身体やそこへ至る過程には無理が生じてしまうのが普通ですから。プレチニックは彼の全人生、そしてある限りの創造性をこの一つの空間へと集中させたのです。想像するに、ドアの枠の上に重い梁が取り付けられているのもそのためでしょう。その梁が休むための空間と働くための空間とを象徴的に分けているのです。

もう一つ考えられる理由は、もっと形式的なものです。つまり彼は、イタリアの格式高い建築とリュブリャナやその周辺の粗末で農村的な建築のどちらにも強く影響を受けていました。彼は地方の村をたくさん訪れていました。ですから、このシリンダー状の形は、それらの地方の典型的な城の搭から来ていると考えることもできますね。おそらくスピリチュアルな事とも関係するのでしょう。信仰の砦という言葉は、プレチニックの時代によく使われたメタファーでもあるのです。

全く正反対な二つの空間のコントラストが興味深いのですが、どうお考えですか。つまり、仕事と睡眠のための中央の円形の部屋と、ガラス張りの細長い長方形のベランダの二つの空間の関係についてどうお考えかお聞かせください。

建築の歴史において中心的な空間というのは、通常、神への献身や完璧性を意味しますよね。一方、対称性や集中性のない幾何学というものは、自然や都市に現れてくるものですし、儀式性のない、もっとリラックスした形で機能するものです。この家においては、二種類のタイプの部屋が一直線上に繋がっていて、一方からもう一方へと簡単に移動することができるようになっています。

プレチニックは、家は教会と同じ設計原理で建てられるべきだと考えていました。そう、彼の家の主な建築的形態は、神聖な空間を意味しているものです。方向づけられているものでもなく、誰かと一緒にいるための空間でもない。円という絶対的な形が、空間に自律性を与え、それゆえに教会の空間と似てくるわけですね。古典的な設計の考え方からすると、家というものは、もっと他の要素、いわば絶対的でない要素によって、周囲と繋がりを持つ必要があると考えるべきなのです。だから、構成的にこの家を考えると、とても面白い。メインスペースと周辺環境とは、一定の距離を保っていますよね。あるいは、中間的な空間によってフィルターがかけられているという感じでしょうか。

これらの外部空間がアンカーとなり、家を周辺の文脈の中に結びつけているのです。玄関への小道、教会、庭、そして実験用モックアップで溢れた畑との密接な関係を作り出しているのです。これらが家をある種のエコシステムへと組み込んでいるわけです。家は要素ごとに分解されてしまうものではなく、全てが融合しつつも、個々の要素が認識され得る状態にあるのです。つまり、それぞれの実体や性質が保持されながらも、有機体である臓器のようにそれぞれが支え合って役割を担っているのです。

篠原も相反する空間をつなぎあわせて、コントラストや突然の変化を強調する操作をしていたと思います。一方、プレチニックには、根本的に異なる性格の空間を組み合わせながらも、調和や安らぎを作り出そうとする努力が感じられるのですが、どう思われますか?

篠原も象徴空間と機能空間とを区別していますね。しかし、コンセプトの明確さにおいては、プレチニックとはかなり異なります。趣味や性格の問題だと思うのですが。篠原はとても「Sushi」的な人なのでしょう。寿司では全てがあるがままという感じですよね。魚と米とをくっつけるのですが、それらを媒介する要素は何もないわけです。ソースもありません。醤油は、一貫ずつ後からつけるものですしね。

個人的には、プレチニックは全くそういう人ではないと思うのです。彼はGesamtkunstwerk(総合芸術)を求めていました。伝統と象徴との関係に依拠しながらも、細部まで構想しつくし、構成されたシームレスで一貫性のある建築を求めたのです。篠原は、矛盾や亀裂などの概念に依拠していたと思いますが。

プレチニックの設計方法を理解するには、一階の応接室が重要です。ごく限られた親しい友人だけが招かれた場所です。建築家は、かなり人を選別していたようですね。他の人は、ただ待たされたのです。この応接室は、他とは異なる特別な雰囲気のものでした。それでも、この部屋はしっかりと全体的なデザインコンセプトの中に組み込まれているのです。空間同士の間に強いコントラストを感じずに流動的な体験ができるのは、おそらく一人の建築家の手によって作りこまれているからなのでしょう。重要なのは「手」という言葉です。篠原の場合は、もっとコンセプチュアルでしょう。クラフト性やドローイングというよりは、心や知性に訴えかけようとするものです。彼は、家が数学をするかのように、対立や分割、そして差異を求めるのでしょう。

プレチニックの場合は、背景の精神的なアイデアが全てを統一しているのです。もちろんそこには宗教や、彼の出自としての分離派のGesamtkunstwerk(総合芸術)のアイデアが関係しています。建物は形式的な概念ではなく、精巧なディテール、精緻な素材の利用、そして要素同士の均衡関係、などに労力がかけられることで、少しずつ統合性を獲得していくものなのです。つまりプレチニックはドラフトマンなのです。篠原が数学者であるのとは対照的ですね。まあ、篠原のデザインにもスケッチは重要な役割を果たしているのですが。

この家は、おばあちゃんでも住みたいと思えるものでしょうか?

ええ、もちろん。それは建築の表現とも関係していると思います。建築的な要素があなたにダイレクトに訴えかける、そんな建築なのです。柱を見れば、あなたは柱と対話を始めますし、彫刻を見れば、あなたの視線と彫刻とが絡み合うのです。プレチニックは抽象化することに全く興味がなかった。彼の家は理解しやすいですし、単純に住みやすい。家庭的でさえある。

とはいえ、装飾や中のオブジェがなくてもこの家は成立すると思うのです。古典的なボキャブラリーがなくなっても問題ないでしょう。プロポーション、素材、境界の作り方、それに心地よさの点において、非常にうまくできています。

こういった点がプレチニックをモダニストたらしめているのでしょうか?それともまだ彼は、保守的でセンチメンタルな伝統に属していると思われますか?

彼の家の場合、既存の文脈を捉えながら、その姿を完全に作り変えてしまう、そういった建築の遂行態度が極めて現代的なのです。個々の部屋を見ると、どれも外部空間との関係を持っていますよね。これもまた非常に現代的な考えです。ところが、古典的な形態、古典的な構成、そして伝統的な要素は、数えればきりがないほどです。

つまり、どちらでもあるという感じですか。彼は、リュブリャナ市から直接依頼があったわけでもなく本能的に、リュブリャナを作り変える計画を始めているのです。二、三人でビールやワインを飲みながら議論していたのでしょう。信仰や、リュブリャナという都市についてや、スロベニアのアイデンティティ全般についてなどを話し合っていたのです。街をより良く、より美しくするために彼らは共に活動していました。プレチニックはただデザインを進めていきました。そして自ら街を作り変える責任を負ったのです。とても先進的な手法でした。市からの依頼ではなかったわけですから。お金が得られるわけでもなく、ただ進めていったのです。

一方、プレチニックは極めて古臭い人間でした。進歩や変化を受け入れてはいましたが、重要だとは思っていませんでした。それは、彼の信仰が原因だと思います。信仰の仕方もまた非常に古臭いものでしたし、ガウディとよく似ているのです。作品においては、どちらも最先端のアイデアを生み出しているのですが。

プレチニックは、アバンギャルドとしてのモダニズムのドグマに対して消極的であったようです。一方、馴染みのある形態を新しく配列し直すことで、周囲の環境を全く作り変えるといったことにはオープンな考えを持っていました。それは、本質的に非常に現代的なものなのですが。つまり逆説的にも到達点が同じなのです。

このことを、彼の信仰と正確にリンクさせていくことはできませんが、信仰との結びつきがとても生産的なものであったことは確かです。ガウディのことも一緒に考えると、私たちの時代における「クリエイティビティ」とは違う意味での「クリエイション」という言葉が、彼らの世界に対する意思の源であったように思えるのです。そのクリエイションを、人間的で自然な本性に由来するものだと考えるのであれば、それは今でも私たちの時代と確かに関係しているのです。トートロジーを承知の上で、ですが。ここで言及しているクリエイションとは、ブルーノ・ラトゥールが言うような、地上にあり、地球に束縛されたものに関わる概念としてのクリエイションです。

あなたが好きで良く知っている住宅の中で、プレチニックの家とは、性質や根本的な考え方が正反対なものはありますか?

正反対なものを探すとすれば、周囲から隔絶された家を選ぶことになりますし、それが主なポイントとなるでしょうか。建築のためだけに存在する建築。つまり極度に自律的な建築です。行ったことのある中でよく知っているのは、モスクワのコンスタンチン・メルニコフのアトリエ兼住宅ですね。19世紀末から20世紀初頭の周辺環境からは見事に孤立しています。特定の場所や文脈のためというよりは、理想的な型として設計されたものです。つまり文脈とは何の関係もない。

いや、もっと正確に考えると、社会的、政治的、あるいは具体的で、物質的な文脈という意味においては、もちろん文脈的な産物です。でもまあ、否定的に捉えれば、未来から降ってきたような家ということです。

プレチニックの家が興味深いのは、そこが家庭そのものであるからです。ラ・サラチェーナやコルビジェの小さな家、あるいは谷川さんの住宅が持つような住居性を超えたものです。私はいつも立ち返ってこのことについて考えるのですが、つまりそれはエコシステムなのです。建築家はそこに住んでいました。表現のスタイルや建築的エレメントを、家の中や、家の周りで試していたのです。アアルトがアトリエでやっていたようにです。プレチニックは、はじめに家の周囲を作り直し、次に家の庭と教会の庭との関係を作り直しました。そして都市との関係を考え始めたのです。この家は、家庭的なものであると同時に、より広域なネットワークの中での、ある種のノードとして機能しているのです。個人的なものでありながら、真の意味でパブリックなものですから。

2021年12月04日

Tibor Joanelly: Shortly before starting work on Shinoharistics, I had intended to write an essay about three architects and three houses they had designed. The collection was to be Kazuo Shinohara, Luigi Moretti and a third one. At the time, I was never sure, whether to write about Jože Plečnik or Sigurd Lewerentz. In the end I figured out that Shinohara’s gravity was just too strong to combine with others, so I decided to write specifically about him and Tanikawa house. Nevertheless, Plečnik remains a very interesting subject and one day, I can imagine writing Plečnikistics.

WHAT DO KAZUO SHINOHARA AND JOŽE PLEČNIK HAVE IN COMMON?

Most obviously, their research resonated strongly with a national tradition and consequently influenced the sense of identity of each of their respective countries. Shinohara looked for the Japan-ness of space, whereas Plečnik defined the character of the most important public spaces in his capital city, Ljubljana and became the author of many symbols taken up by a then young Slovenia. Another important similarity between their characters is the cult of the master that they created around themselves, establishing schools and movements founded on their own ideas, with significant numbers of devoted followers. However, apart from these things, I think, they were overall rather different.

IS PLECNIK’S HOUSE PART OF THE SURROUNDING SYSTEM OF OLD HOUSES THAT IT IS FOUND AMONGST, OR IS IT A NEWCOMER, AN INTRUDER IN THE EXISTING TIGHT NIT CONTEXT?

Well, that depends which version you refer to, for instance, the first design was very close to Shinohara’s House in Yokohama, a kind of moon lander. It was very centralised, very singular. In the later versions, the project, thanks to some additional elements, became more linked to the surroundings. I believe this made the building much better.

Today, you enter through a very narrow alley and arrive to a courtyard flanked by the old building and closed on the front side by the volume of the later addition, designed by Plečnik. If you pass by the winter garden, the courtyard opens towards a big piece of land. The new part, where Plečnik used to live, is oriented towards the garden, adjacent to the yard of the church. This is the first, very basic reading of the situation.

The story goes, that he bought the plot for himself, his brother and sister. Unfortunately, their cohabitation didn’t really work out because the architect was very sensitive and could not be disturbed. Although he depended on both the presence and work of others, Plečnik really needed a concentrated, secluded life in order to work and think.

The house itself reflects this paradoxical situation. It blends contextual integration - formally and functionally melding the old with the new, and an ambitious autonomy - building a space for a very particular individual, taking into account many personal fascinations and preferences.

The house relates not only to its immediate context. It is also connected to the wider city. Beautiful parts of Ljubljana, the whole promenade following the Ljubljanica, the library etc. were all conceived in this house, and the house itself became a testing ground for architectural fragments. Once designed, elements were mocked up and placed in the garden to check how they looked and if they worked or not. Plečnik also used to keep the models of his projects for the city, displaying them in the staircase and in the drawing room upstairs. Through these models the city became very present within the house. And he obsessively collected antiques, often related to his own experience. These influences were in turn spread all over Ljubljana. Plečnik really established a kind of metabolism between house and city, between present and past.

WAS THE HOUSE THE EPICENTRE OF A CULTURAL EARTHQUAKE, SHAKING THE WHOLE CITY?

It has a quality like that, although I don’t know too much about the cultural transitions that Ljubljana and Slovenia went through at that time. But in this context, the house must have become a kind of medium by which the cultural transformation was gaining momentum.

Although a private man, ultimately, Plečnik’s personal interests became extremely public – and vice versa, the city became present in the house. It is for this reason that the house remains, for me, interesting. At the same time the house is both unique, and in dialogue with completely diverse contexts.

Plečnik consciously cut himself off from the publicness of the street and decided to live towards the garden, in an intimate relationship with the adjacent church yard. Before, the garden was ordinary, utilitarian, as one finds everywhere in the east, in the yards of old villages or petty bourgeois houses. The garden served for growing food or keeping animals, it was an essential resource. But Plečnik completely changed its meaning by ennobling both, the yard, and existing houses.

This attitude is well expressed in the garden at the side of the house which exudes a classicist castle-like attitude and creates a strange dichotomy – at once being a very closed world, known only to itself, whilst, through the architect’s lived commitment towards the city, opening to a much broader context. Interestingly, the garden was still used for growing plants, for which neighbours were welcomed to cultivate for their own purpose.

It’s important to mention, that the main access to Plečnik’s house was, at that time, along a path that follows the border of the church yard and not through the old house from the street. His guests, students and for that matter, clients had to symbolically cross the domain of the church to access the architect’s house. There they had to wait on a veranda, sometimes for hours until he came to the door and greeted them. I think, it’s a very architectonic approach to staging everyday life - very theatrical. As a young student this is what attracted me to it. You cannot really move around the house without practicing a kind of enforced ritual, choreographed by the architectural arrangement. And I feel a strong pull – like a tractor beam – towards such a religious commitment, although I consider myself an atheist (I’m not even baptized).

WHAT DO YOU REFER TO WITH THE WORD RITUAL?

Ritual was omnipresent in all classical cultures before modernism. Plečnik was deeply rooted in them and understood the potential of rituals in the sequencing of his architecture.

For instance, the entrance veranda is much more than just an entrance. It’s like entering the Acropolis, you have a sort of Propylaea, entering becomes a procession. The propylaeum is a topic that Plečnik used almost everywhere to differentiate the reality he built from everything around. It introduced a suspense, a tension and set a solemn place of transition.

In almost every building he drew, you have the large, heavy, black columns and a sacred path that both frame and lead you into the plan.

WHY DO YOU THINK THE MAIN ROOM IS CIRCULAR?

There is surely a reference to the main hall in a baroque castle, projecting towards the garden. Together with the three windows, the circularity creates a very strong symmetry and a very strong axis towards the outside. And, beyond that, the house, with the rectangular roof, reminds a free-standing column with strange proportions… An architect with a fascination for columns himself inhabits a column – what a striking, witty image!

The circular shape is also a very concentrated form. He used it to explore the close connection between different activities. It is interesting, because even if your ambition is to completely dissolve your life in a discipline or dedicate yourself completely to something, the opposition of bodily needs and the creative process remains. Plečnik concentrated his whole life, his whole creativity within this one space. I assume, that’s why he introduced a heavy beam, resting above the door frames. Symbolically, it separates the space for rest and the space for work.

Another reason that comes to my mind is more formal. He was strongly influenced by both high Italian architecture and the more rudimentary peasant architecture of Ljubljana and its surroundings. He travelled and visited many local villages. The cylinder could be seen as the tower of a castle, typical of that region. I guess, it also had something to do with spirituality. The stronghold of faith was a popular metaphor in the times of Plečnik.

I FIND THE CONTRAST BETWEEN TWO COMPLETELY OPPOSITE SPACES INTERESTING. NAMELY, THE COMBINATION OF THE CENTRAL CIRCULAR ROOM, A PLACE OF WORK AND SLEEP, WITH THE VERANDA - A RECTANGULAR COMPLETELY GLAZED AND ELONGATED SPACE.

A central space in architectural history was usually meant to be a space of cult, of dedication to divinity, of perfection. Less symmetrical, less concentrated geometries were often more exposed to the nature or to the city, working in a less ceremonial, more relaxed way. Here the two types of rooms are connected along one straight line, you can just switch from one to another very quickly.