ジョナサン・サージソン: ステファン・ベイツと私が事務所を立ち上げたとき、私たちは戸建て住宅よりも集合住宅の方に興味がありました。一人のクライアントのための家をつくるような狭いフォーカスではなく、もっと広く社会へ貢献できるような集合的な建築の形式をつくりたかったのです。

とはいえ、正式に事務所を設立した1996年より以前から彼と一緒に取り組んでいたプロジェクトのことを思い返してみると、最初のプロジェクトは、ステファンの友人の家の計画でした。その友人は、スペインの南部に素晴らしい土地を購入していました。そこからは遠景にモロッコとアトラス山脈を望む丘陵地帯が見渡せました。かなり長い間、力を入れて取り組んでいたのですが、残念ながら、現場に入る直前に中止してしまいました。

当時、私たちは、アリソン&ピーター・スミッソンのサグデン邸に強く影響を受けていたのです。普通であることをはっきりと示した建築の事例ですね。同様に、私たちのプロジェクトも地域性や、ある種の普通さ、平凡さ、土地や伝統との調和を探求するものでした。ワトフォードのこの小さな郊外の住宅は、私たちのこのようなテーマに対する興味を手助けしてくれるものでしたが、お互いのプロジェクトの文脈はかなり異なっていました。

サグデン邸は、50年代半ばのイギリスにとっては、ラディカルなプロジェクトだったと思われますか?

普通であることをコンセプト化した点では、まさにラディカルなものだったと思います。いや、本当に普通の家なのでしょうか?その形はとてもシンプルに見えますし、バナルと言ってもいいですね。地区計画の規制にも従っています。ところが、庭に対する開口部の配列やファサードの構成は、慣習的なやり方ではないですよね?

あらゆるデザイン上の判断が、ちょっと変に感じる境界線上にあるんです。一見すると南イングランドの郊外住宅のように見えるんですけどね。建築家というのは、ある種の創造に対する野心を持って仕事をしているわけですが、それはまさに、寸法とかスケールとかを決めていくことですよね。

このことは建築を始めたばかりのころに強く意識していたことを覚えています。1990年代初めのイギリスでは保守主義の考えが広がり始めていて、それに対抗するために、普通であることを利用していくことは、戦略たり得ると発見したのです。声高な建築的主張がないように見せることは、正直に言って、役所の計画部門の監視をすり抜けていく方法でもありましたし、また、私たちにとっては、差別化を図るための解決策や話題を、密かに運び出していくような方法であったわけです。ロンドンのシェパーデスウォークのプロジェクトを進めているときのことですが、相当頭のきれる計画部門の担当者がいて、こう尋ねてきたことを覚えています。教えていただいても良いでしょうか?これはジョージアン様式の劣化コピーなのでしょうか、それともあなた方のアプローチの背後には何かあって、それについて我々は話し合うべきでしょうか?非常に鋭いと思いましたね。

結局、このプロジェクトの表現上の特徴は、静かで平凡なものであったのに、それに対する反応や大衆からの受け止められ方は実際、何かが違う、といった感じでした。存在を消すことに失敗したんです。

サグデン邸では、伝統的な郊外の規則的な部屋の配置計画が、明快なメインスペースを形成するコンクリート梁の構造的解決によって打ち消されていますよね。この家の空間構成における主な要素は何だとお考えですか?

一階は、スカンジナビアの建築からインスピレーションを得ていますね。家の中の様々な領域をフレキシブルに構成できるような、よりオープンな暮らし方を約束してくれるものです。二階は、まさに部屋、そして空間の集合体としてのこれらの部屋のバランスによって決まっています。

この二つの特徴の組み合わせが空間の豊かさを生み出していますし、この家の主な建築的特質となっていると思います。

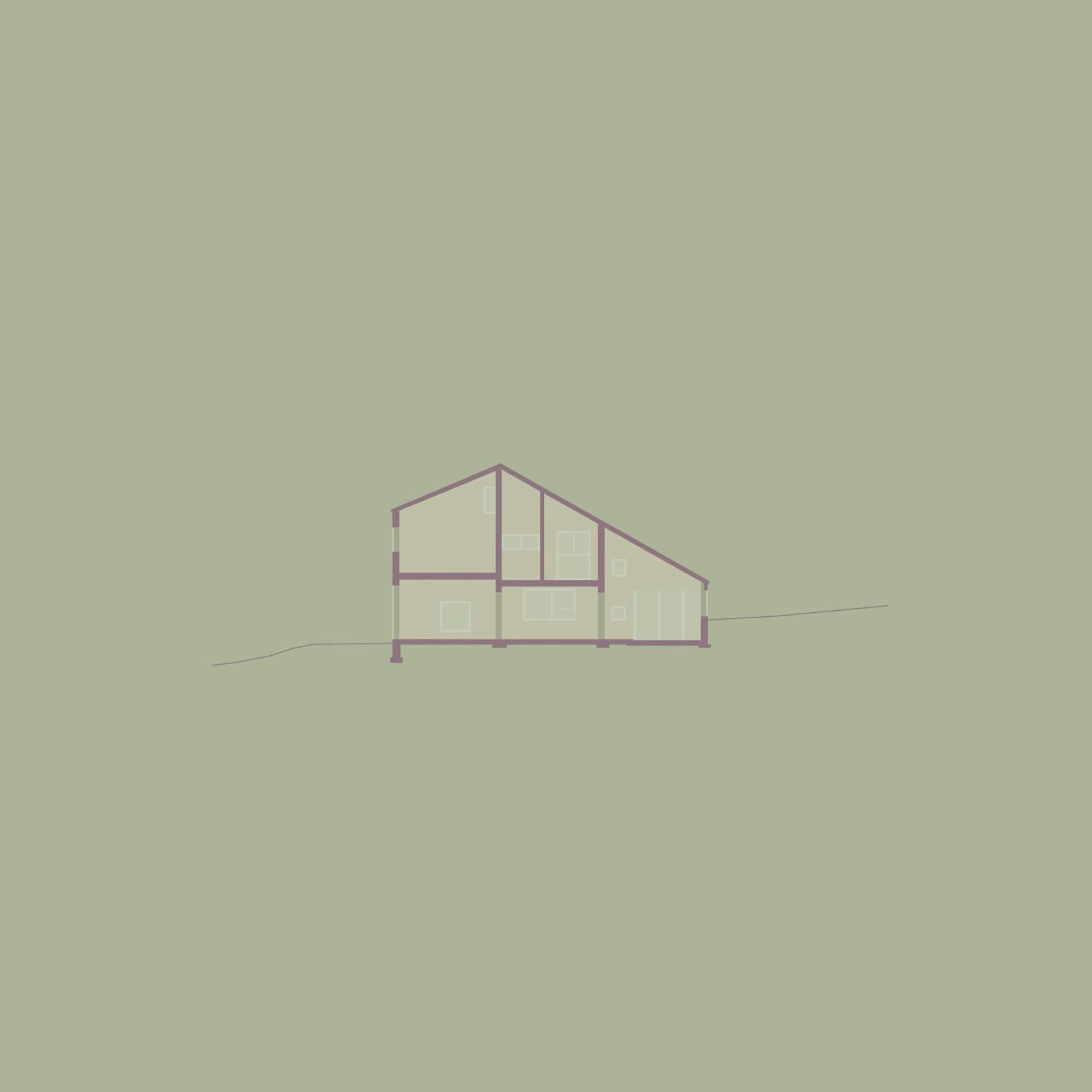

一階の平面図だけを見ていては、なかなか理解することはできません。この家は断面で理解する必要があるのです。

この家のイメージについて話をしたいと思います。この家の開口部は、押し付けられた秩序から来ているのではなく、内部で生じる現象に従ったものだと思いますが、どうでしょうか?

郊外の住宅としての役割を自覚しながら、それでいて大きな気負いを感じさせない住宅ですよね。私が特に魅力的だと思うのは、L字型の窓です。そのモチベーションは何だったのだろうかと、よく考えていました。単なる構成というわけではないのです。窓と人の姿がどう関係を持つのか、に対して興味があったのだと思います。住人にとっては、庭に対しての露出が二倍になるわけです。L字型の直立部分と水平部分とでは、風景との繋がり方が違いますよね。プロポーションの面白さの探求の結果でもありますが、この家の寛容さをも示しているのです。第一に重要なことは、内部と外部との関係性ですね。

他に注目すべきは何よりも、窓枠が壁の厚みに対してどう設置されているかです。サグデン邸では最もバナルな解決策が取られています。つまり、レンガ一枚の厚み分だけセットバックしているのです。窓枠を開口部の奥に設置することで重厚感を出そうとしているわけでもなく、また外壁と同一平面上に設置することで抽象化しようとしているわけでもないのです。スミッソン夫妻の解決策は、シンプルにこう言っているのです。穴のあいたレンガ壁ですよ。特別な工夫なんてないですよ、と。そのディテールは、窓の納まり方として、また積層された壁との関わり方として、それが最も素直な方法であることを受け入れているのです。

スミッソン夫妻には、機械のようなオブジェクトと、居心地の良い住宅の両方を作るといった建築的判断における矛盾がしばしば見られると思うのですが、どのようにして、この多様な魅力が一つのキャリアとして成り立っているのでしょうか?

サグデン邸のオーナーである、デレク、そしてジェーン・サグデンと知り合うことができたのですが、デレクは、この家を依頼したこと、アリソン、そしてピーター・スミッソンと一緒に考えてきたことをざっくばらんに語ってくれました。彼は、スミッソン夫妻のことを知っていて、彼らを選んだのです。彼らは、Arupのエンジニアであったデレクの仕事を通して会ったことがあったのです。

当時、スミッソン夫妻は、新進気鋭の若手事務所として認識されていました。デレクが私に教えてくれたことなのですが、スミッソン夫妻が、このプロジェクトの最初のアイデアをプレゼンしたときのことです。ジェーン・サグデンが即座に、バタフライ屋根の家なんて絶対にノー、と言ったそうなのです。彼らはメンテナンスしやすいものが良かったのです。毎年秋になるとハシゴに登って、雨樋の落ち葉を掃除することになるなんて嫌だと言ったのです。アリソンは怒って打ち合わせから飛び出していきました。彼女は、作品を批判されて気が動転していたのです。口火を切ったのは、ピーターでした。こう言ったそうです。「わかりました。あなたの批判にお答えできるよう考えます。あなたのためのデザインができないとしたら、他に誰のためのデザインができましょうか?」この逸話から、彼らの人柄、ラディカルな建築を作るという野心、それに加えて、クライアントの批判を受け止めながら、それに応えようとするピーターの賢明さがうかがえます。

このプロジェクトが終わってすぐに、彼らは全く異なるタイプの「House of the future」プロジェクトを手がけていますね。あなたもこういったタイプの仕事をされたことはあるのでしょうか?

「House of the future」のように特定の敷地を想定せず、プロトタイプ的な質を求めるような依頼はいくつかありました。一つは、ホームオフィスとして庭に設置して使えるようなものです。買ってきて庭で組み立てられるようにしたものです。

同じような考えで、自転車通勤をする人のためのシャワーや更衣室を備えた建物を依頼されたこともあります。エレメントをキット化したような学校を設計したりもしました。数多くの「場所のない」プロジェクトに取り組んできましたね。

ただ、建物は、場所によって特徴づけられるものであるということは、私たちのアプローチ方法としていつも強く意識していることなんです。場所は、答えの一部であって、デザインを特徴づけてくれるものだと信じています。私にとっては、その場所へ応答する可能性を模索する方がはるかに面白いことなのです。それに地理学的な多様性は、デメリットではなくむしろメリットだと思うのです。知りすぎていることは、息苦しくもありますし、多様性から豊かさは生まれるものですから。

この家のどういったところに、コンテクストから自立した普遍性があるのでしょうか?

例えばですが、このシンプルな形。子供の描いた家の絵のようですね。この家は、スミッソン夫妻が1993年に出版した「Changing the Art of Inhabitation」の中で述べている、家が持つべきシンプルな資質に関しての記述で、その序章に使われていて、非常に普遍的な特徴をもっているのです。

そこには、アリソン・スミッソンによるものと思われる一連のメモとスケッチが掲載されています。家とはどうあるべきかが語られています。家に住むことに関する素晴らしい覚え書きです。窓の周りに繁茂するツタ。床にこぼれ落ちる光。さまざまな位置からの景色の見え方。家を作るにあたって何が重要なのか、とても基本的でありながら、詩的な観察が語られています。ステファンと私にとっては、とても感動的で刺激的でした。家庭的なことに対するアプローチを改めて考えさせられました。

サグデン邸で好きなところは、サグデン夫妻が若い家族として、そして限られた資金で、ロンドンの郊外であるワトフォードに土地を買い、家を建てたということなのです。

標準的な作りの質素な家ですが、彼らはそこに生涯住み続けたのです。シンプルな要求に対するひたむきさを感じる美しい話でしょう。これは普遍性に対する別の側面であり、家の構成に関するものとは関係ありません。ただ、建築や住まいに対する一般的な私たちの態度と密接に関係していることです。

サグデン邸とは全く異なる住宅で、好きな住宅といえば、どんな住宅を思い浮かべますか?

具体的な例で言えば、ハイゲイトにある、ジョン・ウィンターの住宅は素晴らしいですね。

彼の北米での生活や仕事の経験、そしてミース・ファン・デル・ローエの晩年の作品との繋がりが明確に見てとれます。コンスタンティニディスの作品は、ギリシャの風景の中に家を建てることに対して、ほとんどアルカイックとも言えるアプローチで、いつも魅了されています。シザが駆け出しの頃に手がけた住宅も、本当に面白いですね。

他に素晴らしい住宅といえば、ロンドンにあるトニー・フレットンのレッドハウス。ヴィラ・アレムにも泊まりましたよ。友人でもあり、同僚でもあるヴァレリオ・オルジアティがアレンテージョに建てた住宅です。マスターピースだと思います。住居建築として素晴らしい事例です。私自身のために作った家もけっこう好きですよ。ロンドンのジョージアンハウスを改装したもの。それと、メンドリジオの近く、モンテにある築350年のティチーノ地方の家を改装したもの。

私は昔から家での暮らしに興味をもっていましたし、そこで起きるそれぞれの物語にはいつも刺激を受けています。例えば、日本では住人が生きている間過ごすためだけに家が作られて、その後は、取り壊されるのが普通ですよね。ところがイタリアでは、代々受け継がれる豪邸があって、その精神や本来もっていた威光を維持していく責任を相続人は感じていたりするわけです。多様な文化的、物理的条件がどのように建築に影響を与えているか考えることは、私にとっては、永遠に魅力的で探求しがいのあることですね。

2021年8月10日

Jonathan Sergison: When Stephen Bates and I set up in practice we were more interested in housing than houses. We wanted to make a more collective form of architecture that could serve society more widely than the narrow focus that comes from making a house for a single client.

And yet, when I think about the projects we worked on together even before we formally established our practice in 1996, one of the first was a house for a friend of Stephen’s. He had bought an amazing piece of land in the south of Spain, overlooking a hill town with distant views of Morocco and the Atlas Mountains. We worked intensely on this project for quite a while, but unfortunately it was cancelled just before going on site.

At the time we were very inspired by Sugden House by Alison and Peter Smithson, an example of architecture that is explicitly about ordinariness. Similarily, our project, was an exploration of regionalism, a certain kind of normality and ordinariness, of harmony with the site and tradition. Our interest in these themes was helped by this little suburban house in Watford even though the context was so different.

DO YOU THINK THE SUDGEN HOUSE WAS A RADICAL PROJECT IN THE MID ‘50S IN ENGLAND?

I think it really was radical in the way it conceptualised ordinariness. Is it really an ordinary house? Its form could be seen as something very simple, almost banal, dictated by planning regulations. But the arrangements of the openings and the composition of the facade in relation to the garden – that’s not a conventional way of making windows, is it?

Every decision is on the edge of being a little bit strange, even though at first glance it looks like any of the suburban houses we see in the south of England. As an architect, you’re working with a certain kind of creative ambition, and it’s really about the measure and scale at which you try things out.

I remember this was a strong inspiration in the early days of our practice. We discovered that playing with ordinariness could be a strategy to deal with the prevailing conservatism that existed in the UK in the early 1990s. To make something look like it’s not a big architectural statement was, frankly, a way of getting past the scrutiny of planning departments and allow us to smuggle solutions and topics that would make a difference. When we developed the project on Shepherdess Walk in London, I remember that the planning officer, who was rather smart, asked: ‘Can I just be clear? Is this a bad copy of Georgian architecture or is there something else behind your approach, that we should talk about?’ I found that rather perceptive.

In the end, even though the representational character of the project was quiet and ordinary, the reception it got and the way it was perceived by the public was, indeed, that it was somehow different. We failed to make it invisible.

IN THE SUGDEN HOUSE, A TRADITIONAL SUBURBAN REGULAR LAYOUT IS DECONSTRUCTED BY A STRUCTURAL SOLUTION OF CONCRETE BEAMS THAT CREATE A CLEAR MAIN SPACE. WHAT DO YOU THINK ARE THE MAIN SPACE-MAKING ELEMENTS OF THE HOUSE?

The ground floor is inspired by Scandinavian architecture - the promise of a more open way of living, where different territories of the house can be more flexibly organised. Upstairs, it is really about rooms and the proportion of these rooms as a collection of spaces.

I think the combination of these two characteristics produces the spatial richness and is the main architectural quality of the house.

If you judged the building by looking at the first-floor plan only, you wouldn’t get very far. This house must be understood in section.

LET’S TALK ABOUT THE IMAGE OF THE HOUSE. IN THIS CASE, THE OPENINGS FOLLOW WHAT HAPPENS INSIDE RATHER THAN ANY IMPOSED ORDER.

Knowing its role as a suburban house, it doesn’t have big pretensions. One of the things I find really fascinating are the L-shaped windows. I’ve often wondered what the motivation was behind the design. It’s more than just composition. I think there’s a certain interest in the way a figure relates to a window. It doubles exposure to the garden for the residents. The upright part of the L-shaped window and the horizontal part connect with the landscape in different ways. It’s an interesting proportion, but also proof of the generosity this house offers. It’s first and foremost about the relationship between inside and outside.

Something else to note is the all-important question of where the window frame sits in relation to the thickness of a wall. In the Sugden House we have the most banal solution - it’s set back by the thickness of a brick. It’s not trying to create a sense of heaviness by setting the window assembly deep within the reveals, nor of abstraction by placing it flush with the outside face. The Smithson’s solution simply says, ‘I’m a brick cavity wall’ - there is no rhetoric. It accepts the truth of the most straightforward way of detailing the window and how it relates to the buildup of the wall.

THE SMITHSONS WERE OFTEN CONTRADICTORY IN THEIR ARCHITECTURAL DECISIONS, BUILDING BOTH MACHINE-LIKE OBJECTS AND COSY HOUSES. HOW WAS IT POSSIBLE TO FIT DIVERSE FASCINATIONS IN ONE CAREER?

We got to know the owners of the Sugden House, Derek and Jane Sugden. Derek was very candid in the stories he told about commissioning of the house and working with Alison and Peter Smithson. He chose to work with them because he knew them, they’d met through his work as an engineer at Arup’s.

At the time the Smithsons were considered an up-and-coming young practice. I remember he told us that when they presented their first ideas for the project Jane Sugden immediately said there was absolutely no way they were going to have a house with a butterfly shaped roof. They wanted something that would be easier to maintain. They said they were not going to climb up a ladder every autumn to clean the leaves out of the gutter. Alison stormed out of the meeting. She was very upset with any criticism of their work. It was Peter who said: ‘Well, you know, we’ll find a way of responding to your critique. If we can’t design a house for you, then who can we design a house for?’ This anecdote shows their character and their ambition to make radical architecture, but also Peter’s wisdom in elegantly accepting the clients’ criticism and responding to their needs.

SHORTLY AFTER THEY FINISHED THE PROJECT, THEY DID THE HOUSE OF THE FUTURE, SOMETHING TOTALLY DIFFERENT. HAVE YOU ALSO ENGAGED IN EXERCISES OF THIS KIND?

We did work on several commissions which, like the House of the Future, were not intended for a particular site, but had a prototypical character. One was a building that could be used in a garden as a home office, that could be bought and assembled in a garden.

In a similar spirit, we were commissioned a building to accommodate showers and changing facilities for people who cycle to work. We also designed a school building as a kit of elements. We worked on a number of ‘place-less’ projects.

However, a strong aspect of our approach has always been a sense that the place where the work is situated should inform the approach to building. We believe that place should be part of the answer and inform the design. For me, it’s much more interesting to explore possible responses to place. I would also argue that geographical variations are definitely an advantage, rather than a disadvantage. I think familiarity can be stifling, while richness stems from diversity.

WHAT COMPONENT OF THIS HOUSE COULD BE SEEN AS UNIVERSAL, TAKEN OUT OF CONTEXT?

Its simple form, for instance; it’s almost like a child’s drawing of a house . The house is also a prologue to the Smithsons’ description of the simple qualities a house should offer, published in ‘Changing the Art of Inhabitation’ in 1993, which also has a very universal character.

There you can find a series of notes and sketches – made by Alison Smithson, I believe. They talk about what a house should be like. It’s a wonderful sketchy essay on thoughts about inhabiting a house: a creeper growing around a window, the way the light falls on the floor, ways of seeing a view from different positions. It talks about very basic and rather poetic observations about what is important in making a house. Stephen and I found that really touching and certainly very inspiring. It made us re-think our own approach to domesticity.

What I like about the Sugden House is that the Sugdens bought the plot in Watford, which is part of the wider suburban area of greater London, as a young family and built a house with limited means.

It’s a modest house of standard construction, and they lived in it all their lives. In some sense, it’s a beautiful story of a commitment to something that serves simple needs. This is another universal aspect of it, it has nothing to do with composition, but it is closely connected to our attitude to architecture and dwelling in general.

IF I ASK YOU TO THINK ABOUT HOUSES YOU LIKE THAT ARE VERY DIFFERENT FROM THE SUGDEN HOUSE, WHAT COMES TO MIND?

When it comes to concrete examples, I find John Winter’s house in Highgate an amazing building, explicitly connected to his experience of living and working in North America and to Mies van der Rohe’s late work. And I’ve always had an absolute fascination with the work of Konstantinidis, with his almost archaic approach to the making of houses within the Greek landscape. I am also profoundly interested in the houses Siza made at the beginning of his career.

Another house I think is wonderful is Tony Fretton’s Red House, in London… I also stayed at Villa Além, which was built by my friend and colleague, Valerio Olgiati in Alentejo. I think it’s a masterpiece, a wonderful example of domestic architecture. I’m also rather fond of the houses I made for myself – the remodeling of a Georgian house in London, and of a 350-year-old Ticino house in Monte, above Mendrisio.

The lives of houses have always interested me, and I am always stimulated by their stories. In Japan, for example, it is common to make houses that last for the residents’ lifetime and are then demolished. But in Italy, you have grand houses that are passed from generation to generation, to heirs who feel responsible for maintaining their spirit and original grandeur. The way in which diverse cultural and physical conditions affect architecture is, in my opinion, an ever-fascinating field of exploration.

10.08.2021

当斯蒂芬・贝茨(Stephen Bates)和我开始实践时,我们更感兴趣于供给住宅(housing)而不是住宅(houses)本身。我们想制作一种更加集体化的建筑形式,它可以更广泛地服务于社会,而不是狭隘的关注于为单一客户做住宅。

然而,当我想起我们在1996年正式成立公司前一起工作的项目时,首先想到的是为斯蒂芬的一个朋友建造的住宅。他在西班牙南部买了一块令人惊叹的土地,俯瞰着一个山城,可以看到摩洛哥和阿特拉斯山脉的远方。我们在这个项目上紧张地工作了很长时间,但不幸的是,在开工之前,这个项目被取消了。

当时,我们从艾莉森和彼得-史密森(Alison and Peter Smithson)的苏格登之家(Sugden House)得到了很大的启发,这是一个明确的关于平凡的建筑案例。相似的,我们的项目也是对地域主义的探索,某种特定的规范性和平凡性,与场地和传统的和谐。沃特福德这个郊区小住宅,助长了我们对这些主题的兴趣,尽管文脉是如此不同。

你认为苏格登之家是英国50年代中期一个激进的项目吗?

我认为它在概念化平凡的方式上确实很激进。这真的是一个平凡的住宅吗?它的形式可以被看作是非常简单的,几乎是平庸的,由规划法规决定的。但是,开口的安排和与花园有关的外墙的构成——这不是制造窗户的传统方式,对么?

每一个决定都处于有点奇怪的边缘,尽管乍一看,它就像我们在英格兰南部看到的任何一个郊区住宅。作为一个建筑师,你是带着某种创造性的雄心工作的,这真的关乎于你尝试的尺度和规模。

我记得在我们实践的早期,这是一个强烈的启发。我们发现,考虑平凡可以成为一种策略,以应对90年代初英国普遍存在的保守主义。坦率地说,使一些东西看起来不是一个宏大的建筑声明,是一种超越规划部门审查的方式,并允许我们私自裹挟解答和话题,使一切有所不同。当我们在伦敦开发牧羊女大道(Shepherdess Walk)项目时,我记得规划官员相当聪明,他问:"我能不能说明白一点?这是对乔治亚建筑的糟糕复制,还是你的追求背后有其他东西,我们应该谈谈?"我发现这是相当有洞察力的。

最后,尽管这个项目的表现特征是安静而平凡的,但它得到的反应和公众的看法是,它确实有某种程度的不同。我们没能让它变得不可见。

在苏格登之家里,传统的郊区常规布局被混凝土梁的结构方案所解构,创造了一个清晰的主空间。你认为创造这个住宅元素的主要空间是什么?

一楼的灵感来自于北欧建筑——一种对更开放的生活方式的承诺,住宅的不同区域可以更灵活地进行组织。在楼上,它实际上是关于房间和这些房间的比例,作为一个空间的集合。

我认为这两个特点的结合产生了空间上的丰富性,是这座住宅主要的建筑品质。

如果你只看二楼的平面图来判断这个建筑,你不会有所进展。这座住宅必须根据剖面来理解。

让我们来谈谈这座住宅的形象。在这种情况下,开口是按照内部发生的事情,而不是任何强加的秩序。

以其作为郊区住宅的角色来说,它并没有太多矫饰。我发现真正迷人的地方之一是L形的窗户。我经常想知道设计背后的动机是什么。这不仅仅在于构图。我认为有某些兴趣点,是在人物与窗户的关系上。它使住户加倍地接触到花园。L形窗户的直立部分和水平部分以不同的方式与景观相连。这是对比例的有趣探索,也是这个住宅慷慨的证明。它首先是关于内部和外部之间的关系。

还有一个需要注意的非常重要的问题,窗框坐落于墙体厚度之间的关系。在苏格登之家,我们有一个最平庸的解决方案——窗框退进一块砖的厚度。它并没有试图通过将窗子设置在砖的深处来创造一种厚重感,也没有通过将其与外墙面齐平来创造一种抽象感。史密森夫妇的解决方案只是说:"我是一个砖砌的空心墙"——没有任何修辞。它接受了以最直接的方式来描述窗户的真相,以及它与墙体的砌筑的关系。

史密斯夫妇在他们的建筑决定中往往是自相矛盾的,他们既要建造机械般的事物,又要建造舒适的住宅。如何能在一个职业中满足不同的执迷?

我们认识了苏格登之家的主人德里克和简客苏格登(Derek and Jane Sugden)。德里克非常坦诚地讲述了关于房子的委托以及与艾莉森和彼得-史密森合作的故事。他选择与他们合作是因为他认识他们,他们是通过他在奥雅纳(Arup)的工程师工作而认识的。

在当时,史密斯夫妇被认为是一个新兴的年轻事务所。我记得他告诉我们,当他们提出他们对这个项目的第一个想法时,简客苏格登立即说,他们绝对不可能有一个蝴蝶形状的屋顶的房子。他们想要的是更容易维护的东西。他们说,他们不打算每年秋天爬上梯子去清理水沟里的树叶。艾莉森愤怒的离开了会议。她对任何关于他们工作的批评都非常不满。是彼得说:"好吧,你知道,我们会找到一种方法来回应你的批评的。如果我们不能为你们设计住宅,那我们能为谁设计住宅呢?这段轶事显示了他们的性格和做激进建筑的雄心,也显示了彼得优雅地接受客户的批评并回应他们的需求的智慧。

在完成这个项目后不久,他们做了未来之家,完全不同。你是否也参与过这种演练?

我们做了几个委托项目,像未来之家一样,不是为某个特定的地点设计的,而是有一种原型的特征。 其中之一是可以在花园中作为家庭办公室使用的建筑,可以购买并在花园中组装。

本着类似的精神,我们被委托设计一座建筑,为骑自行车上班的人提供淋浴和更衣设施。我们还设计了一个学校建筑,作为一些元素的套件。我们参与了一些 "无场所 "的项目。

然而,一直以来,我们的追求的一个强有力的层面,是感知到项目的所在地应当提示建筑的目的。我们相信,场所应该是解答的一部分,并为设计提供信息。对我来说,探索对场地可能的回应是更有趣味的。我也认同地理差异绝对是优势,而非劣势。我认为熟悉的东西会令人窒息,而丰富则源于多样性。

这所住宅的哪个部分可以被看作是普世的,脱离于文脉的?

例如,它的简单形式;它几乎就像一个孩子画的住宅。这座住宅也是史密斯夫妇在1993年出版的《改变居住的艺术》中对住宅应该提供的简单品质的描述的序幕,它也具有非常普世的特征。

在那里你可以找到一系列的笔记和草图--我相信是由艾莉森-史密森制作的。他们谈到了住宅应该是什么样的。这是一篇精彩的关于居住在住宅里想法的素描文章:窗边的爬山虎,光线落在地板上的方式,从不同位置看风景的方式。它谈到了非常基本和相当有诗意的观察,关于在建造房子时什么是重要的。斯蒂芬和我发现这真的很感人,当然也很有启发性。它使我们重新思考我们自己的家庭生活方式。

我喜欢苏格登之家的原因是,苏格登夫妇作为一个年轻的家庭在沃特福德买下了这块地,这是大伦敦更广阔的郊区的一部分,他们用有限的手段建造了一座住宅。

这是一个标准结构的小住宅,他们在里面生活了一辈子。从某种意义上说,这是一个美丽的故事,是对满足简单需求的东西的承诺。这是它的另一个普世的方面,它与构图无关,但它与我们普遍的对建筑和住所的态度密切相关。

如果我让你想一想你喜欢的、与苏格登住宅非常不同的房子,你会想到什么?

说到具体的例子,我发现约翰-温特(John Winter)在海格特的住宅是一个惊人的建筑,明确地与他在北美的生活和工作经验以及密斯-凡德罗的后期作品有关。我一直对康斯坦丁尼迪斯(Konstantinidis)的作品非常着迷,他在希腊景观中建造住宅的方法几乎是古老的。我也对西扎在其职业生涯开始时制作的住宅深感兴趣。

另一个我觉得很好的住宅,是伦敦的托尼-弗莱顿(Tony Fretton)的红住宅...我还住过阿伦特茹的阿莱姆别墅(Villa Além),那是我的朋友及同事瓦莱里奥-奥尔贾蒂(Valerio Olgiati)建造的。我认为它是一个杰作,是家庭建筑的一个精彩案例。我也相当喜欢我为自己做的住宅——伦敦一栋改造的乔治亚风格的住宅,以及在蒙特的一栋有350年历史的提契诺住宅,在门德里西奥上面。

我一直感兴趣于住宅的生命,总是被它们的故事所激励。例如,在日本,建造一座持续居民的一生,而后被拆毁的住宅很常见。但在意大利,你有宏伟的住宅,它们代代相传,传给那些觉得有责任保持其精神和原始辉煌的继承人。在我看来,不同的文化和物理条件对建筑的影响是一个永远充满魅力的探索领域。

2021年8月10日

ジョナサン・サージソン: ステファン・ベイツと私が事務所を立ち上げたとき、私たちは戸建て住宅よりも集合住宅の方に興味がありました。一人のクライアントのための家をつくるような狭いフォーカスではなく、もっと広く社会へ貢献できるような集合的な建築の形式をつくりたかったのです。

とはいえ、正式に事務所を設立した1996年より以前から彼と一緒に取り組んでいたプロジェクトのことを思い返してみると、最初のプロジェクトは、ステファンの友人の家の計画でした。その友人は、スペインの南部に素晴らしい土地を購入していました。そこからは遠景にモロッコとアトラス山脈を望む丘陵地帯が見渡せました。かなり長い間、力を入れて取り組んでいたのですが、残念ながら、現場に入る直前に中止してしまいました。

当時、私たちは、アリソン&ピーター・スミッソンのサグデン邸に強く影響を受けていたのです。普通であることをはっきりと示した建築の事例ですね。同様に、私たちのプロジェクトも地域性や、ある種の普通さ、平凡さ、土地や伝統との調和を探求するものでした。ワトフォードのこの小さな郊外の住宅は、私たちのこのようなテーマに対する興味を手助けしてくれるものでしたが、お互いのプロジェクトの文脈はかなり異なっていました。

サグデン邸は、50年代半ばのイギリスにとっては、ラディカルなプロジェクトだったと思われますか?

普通であることをコンセプト化した点では、まさにラディカルなものだったと思います。いや、本当に普通の家なのでしょうか?その形はとてもシンプルに見えますし、バナルと言ってもいいですね。地区計画の規制にも従っています。ところが、庭に対する開口部の配列やファサードの構成は、慣習的なやり方ではないですよね?

あらゆるデザイン上の判断が、ちょっと変に感じる境界線上にあるんです。一見すると南イングランドの郊外住宅のように見えるんですけどね。建築家というのは、ある種の創造に対する野心を持って仕事をしているわけですが、それはまさに、寸法とかスケールとかを決めていくことですよね。

このことは建築を始めたばかりのころに強く意識していたことを覚えています。1990年代初めのイギリスでは保守主義の考えが広がり始めていて、それに対抗するために、普通であることを利用していくことは、戦略たり得ると発見したのです。声高な建築的主張がないように見せることは、正直に言って、役所の計画部門の監視をすり抜けていく方法でもありましたし、また、私たちにとっては、差別化を図るための解決策や話題を、密かに運び出していくような方法であったわけです。ロンドンのシェパーデスウォークのプロジェクトを進めているときのことですが、相当頭のきれる計画部門の担当者がいて、こう尋ねてきたことを覚えています。教えていただいても良いでしょうか?これはジョージアン様式の劣化コピーなのでしょうか、それともあなた方のアプローチの背後には何かあって、それについて我々は話し合うべきでしょうか?非常に鋭いと思いましたね。

結局、このプロジェクトの表現上の特徴は、静かで平凡なものであったのに、それに対する反応や大衆からの受け止められ方は実際、何かが違う、といった感じでした。存在を消すことに失敗したんです。

サグデン邸では、伝統的な郊外の規則的な部屋の配置計画が、明快なメインスペースを形成するコンクリート梁の構造的解決によって打ち消されていますよね。この家の空間構成における主な要素は何だとお考えですか?

一階は、スカンジナビアの建築からインスピレーションを得ていますね。家の中の様々な領域をフレキシブルに構成できるような、よりオープンな暮らし方を約束してくれるものです。二階は、まさに部屋、そして空間の集合体としてのこれらの部屋のバランスによって決まっています。

この二つの特徴の組み合わせが空間の豊かさを生み出していますし、この家の主な建築的特質となっていると思います。

一階の平面図だけを見ていては、なかなか理解することはできません。この家は断面で理解する必要があるのです。

この家のイメージについて話をしたいと思います。この家の開口部は、押し付けられた秩序から来ているのではなく、内部で生じる現象に従ったものだと思いますが、どうでしょうか?

郊外の住宅としての役割を自覚しながら、それでいて大きな気負いを感じさせない住宅ですよね。私が特に魅力的だと思うのは、L字型の窓です。そのモチベーションは何だったのだろうかと、よく考えていました。単なる構成というわけではないのです。窓と人の姿がどう関係を持つのか、に対して興味があったのだと思います。住人にとっては、庭に対しての露出が二倍になるわけです。L字型の直立部分と水平部分とでは、風景との繋がり方が違いますよね。プロポーションの面白さの探求の結果でもありますが、この家の寛容さをも示しているのです。第一に重要なことは、内部と外部との関係性ですね。

他に注目すべきは何よりも、窓枠が壁の厚みに対してどう設置されているかです。サグデン邸では最もバナルな解決策が取られています。つまり、レンガ一枚の厚み分だけセットバックしているのです。窓枠を開口部の奥に設置することで重厚感を出そうとしているわけでもなく、また外壁と同一平面上に設置することで抽象化しようとしているわけでもないのです。スミッソン夫妻の解決策は、シンプルにこう言っているのです。穴のあいたレンガ壁ですよ。特別な工夫なんてないですよ、と。そのディテールは、窓の納まり方として、また積層された壁との関わり方として、それが最も素直な方法であることを受け入れているのです。

スミッソン夫妻には、機械のようなオブジェクトと、居心地の良い住宅の両方を作るといった建築的判断における矛盾がしばしば見られると思うのですが、どのようにして、この多様な魅力が一つのキャリアとして成り立っているのでしょうか?

サグデン邸のオーナーである、デレク、そしてジェーン・サグデンと知り合うことができたのですが、デレクは、この家を依頼したこと、アリソン、そしてピーター・スミッソンと一緒に考えてきたことをざっくばらんに語ってくれました。彼は、スミッソン夫妻のことを知っていて、彼らを選んだのです。彼らは、Arupのエンジニアであったデレクの仕事を通して会ったことがあったのです。

当時、スミッソン夫妻は、新進気鋭の若手事務所として認識されていました。デレクが私に教えてくれたことなのですが、スミッソン夫妻が、このプロジェクトの最初のアイデアをプレゼンしたときのことです。ジェーン・サグデンが即座に、バタフライ屋根の家なんて絶対にノー、と言ったそうなのです。彼らはメンテナンスしやすいものが良かったのです。毎年秋になるとハシゴに登って、雨樋の落ち葉を掃除することになるなんて嫌だと言ったのです。アリソンは怒って打ち合わせから飛び出していきました。彼女は、作品を批判されて気が動転していたのです。口火を切ったのは、ピーターでした。こう言ったそうです。「わかりました。あなたの批判にお答えできるよう考えます。あなたのためのデザインができないとしたら、他に誰のためのデザインができましょうか?」この逸話から、彼らの人柄、ラディカルな建築を作るという野心、それに加えて、クライアントの批判を受け止めながら、それに応えようとするピーターの賢明さがうかがえます。

このプロジェクトが終わってすぐに、彼らは全く異なるタイプの「House of the future」プロジェクトを手がけていますね。あなたもこういったタイプの仕事をされたことはあるのでしょうか?

「House of the future」のように特定の敷地を想定せず、プロトタイプ的な質を求めるような依頼はいくつかありました。一つは、ホームオフィスとして庭に設置して使えるようなものです。買ってきて庭で組み立てられるようにしたものです。

同じような考えで、自転車通勤をする人のためのシャワーや更衣室を備えた建物を依頼されたこともあります。エレメントをキット化したような学校を設計したりもしました。数多くの「場所のない」プロジェクトに取り組んできましたね。

ただ、建物は、場所によって特徴づけられるものであるということは、私たちのアプローチ方法としていつも強く意識していることなんです。場所は、答えの一部であって、デザインを特徴づけてくれるものだと信じています。私にとっては、その場所へ応答する可能性を模索する方がはるかに面白いことなのです。それに地理学的な多様性は、デメリットではなくむしろメリットだと思うのです。知りすぎていることは、息苦しくもありますし、多様性から豊かさは生まれるものですから。

この家のどういったところに、コンテクストから自立した普遍性があるのでしょうか?

例えばですが、このシンプルな形。子供の描いた家の絵のようですね。この家は、スミッソン夫妻が1993年に出版した「Changing the Art of Inhabitation」の中で述べている、家が持つべきシンプルな資質に関しての記述で、その序章に使われていて、非常に普遍的な特徴をもっているのです。

そこには、アリソン・スミッソンによるものと思われる一連のメモとスケッチが掲載されています。家とはどうあるべきかが語られています。家に住むことに関する素晴らしい覚え書きです。窓の周りに繁茂するツタ。床にこぼれ落ちる光。さまざまな位置からの景色の見え方。家を作るにあたって何が重要なのか、とても基本的でありながら、詩的な観察が語られています。ステファンと私にとっては、とても感動的で刺激的でした。家庭的なことに対するアプローチを改めて考えさせられました。

サグデン邸で好きなところは、サグデン夫妻が若い家族として、そして限られた資金で、ロンドンの郊外であるワトフォードに土地を買い、家を建てたということなのです。

標準的な作りの質素な家ですが、彼らはそこに生涯住み続けたのです。シンプルな要求に対するひたむきさを感じる美しい話でしょう。これは普遍性に対する別の側面であり、家の構成に関するものとは関係ありません。ただ、建築や住まいに対する一般的な私たちの態度と密接に関係していることです。

サグデン邸とは全く異なる住宅で、好きな住宅といえば、どんな住宅を思い浮かべますか?

具体的な例で言えば、ハイゲイトにある、ジョン・ウィンターの住宅は素晴らしいですね。

彼の北米での生活や仕事の経験、そしてミース・ファン・デル・ローエの晩年の作品との繋がりが明確に見てとれます。コンスタンティニディスの作品は、ギリシャの風景の中に家を建てることに対して、ほとんどアルカイックとも言えるアプローチで、いつも魅了されています。シザが駆け出しの頃に手がけた住宅も、本当に面白いですね。

他に素晴らしい住宅といえば、ロンドンにあるトニー・フレットンのレッドハウス。ヴィラ・アレムにも泊まりましたよ。友人でもあり、同僚でもあるヴァレリオ・オルジアティがアレンテージョに建てた住宅です。マスターピースだと思います。住居建築として素晴らしい事例です。私自身のために作った家もけっこう好きですよ。ロンドンのジョージアンハウスを改装したもの。それと、メンドリジオの近く、モンテにある築350年のティチーノ地方の家を改装したもの。

私は昔から家での暮らしに興味をもっていましたし、そこで起きるそれぞれの物語にはいつも刺激を受けています。例えば、日本では住人が生きている間過ごすためだけに家が作られて、その後は、取り壊されるのが普通ですよね。ところがイタリアでは、代々受け継がれる豪邸があって、その精神や本来もっていた威光を維持していく責任を相続人は感じていたりするわけです。多様な文化的、物理的条件がどのように建築に影響を与えているか考えることは、私にとっては、永遠に魅力的で探求しがいのあることですね。

2021年8月10日

Jonathan Sergison: When Stephen Bates and I set up in practice we were more interested in housing than houses. We wanted to make a more collective form of architecture that could serve society more widely than the narrow focus that comes from making a house for a single client.

And yet, when I think about the projects we worked on together even before we formally established our practice in 1996, one of the first was a house for a friend of Stephen’s. He had bought an amazing piece of land in the south of Spain, overlooking a hill town with distant views of Morocco and the Atlas Mountains. We worked intensely on this project for quite a while, but unfortunately it was cancelled just before going on site.

At the time we were very inspired by Sugden House by Alison and Peter Smithson, an example of architecture that is explicitly about ordinariness. Similarily, our project, was an exploration of regionalism, a certain kind of normality and ordinariness, of harmony with the site and tradition. Our interest in these themes was helped by this little suburban house in Watford even though the context was so different.

DO YOU THINK THE SUDGEN HOUSE WAS A RADICAL PROJECT IN THE MID ‘50S IN ENGLAND?

I think it really was radical in the way it conceptualised ordinariness. Is it really an ordinary house? Its form could be seen as something very simple, almost banal, dictated by planning regulations. But the arrangements of the openings and the composition of the facade in relation to the garden – that’s not a conventional way of making windows, is it?

Every decision is on the edge of being a little bit strange, even though at first glance it looks like any of the suburban houses we see in the south of England. As an architect, you’re working with a certain kind of creative ambition, and it’s really about the measure and scale at which you try things out.

I remember this was a strong inspiration in the early days of our practice. We discovered that playing with ordinariness could be a strategy to deal with the prevailing conservatism that existed in the UK in the early 1990s. To make something look like it’s not a big architectural statement was, frankly, a way of getting past the scrutiny of planning departments and allow us to smuggle solutions and topics that would make a difference. When we developed the project on Shepherdess Walk in London, I remember that the planning officer, who was rather smart, asked: ‘Can I just be clear? Is this a bad copy of Georgian architecture or is there something else behind your approach, that we should talk about?’ I found that rather perceptive.

In the end, even though the representational character of the project was quiet and ordinary, the reception it got and the way it was perceived by the public was, indeed, that it was somehow different. We failed to make it invisible.

IN THE SUGDEN HOUSE, A TRADITIONAL SUBURBAN REGULAR LAYOUT IS DECONSTRUCTED BY A STRUCTURAL SOLUTION OF CONCRETE BEAMS THAT CREATE A CLEAR MAIN SPACE. WHAT DO YOU THINK ARE THE MAIN SPACE-MAKING ELEMENTS OF THE HOUSE?

The ground floor is inspired by Scandinavian architecture - the promise of a more open way of living, where different territories of the house can be more flexibly organised. Upstairs, it is really about rooms and the proportion of these rooms as a collection of spaces.

I think the combination of these two characteristics produces the spatial richness and is the main architectural quality of the house.

If you judged the building by looking at the first-floor plan only, you wouldn’t get very far. This house must be understood in section.

LET’S TALK ABOUT THE IMAGE OF THE HOUSE. IN THIS CASE, THE OPENINGS FOLLOW WHAT HAPPENS INSIDE RATHER THAN ANY IMPOSED ORDER.

Knowing its role as a suburban house, it doesn’t have big pretensions. One of the things I find really fascinating are the L-shaped windows. I’ve often wondered what the motivation was behind the design. It’s more than just composition. I think there’s a certain interest in the way a figure relates to a window. It doubles exposure to the garden for the residents. The upright part of the L-shaped window and the horizontal part connect with the landscape in different ways. It’s an interesting proportion, but also proof of the generosity this house offers. It’s first and foremost about the relationship between inside and outside.

Something else to note is the all-important question of where the window frame sits in relation to the thickness of a wall. In the Sugden House we have the most banal solution - it’s set back by the thickness of a brick. It’s not trying to create a sense of heaviness by setting the window assembly deep within the reveals, nor of abstraction by placing it flush with the outside face. The Smithson’s solution simply says, ‘I’m a brick cavity wall’ - there is no rhetoric. It accepts the truth of the most straightforward way of detailing the window and how it relates to the buildup of the wall.

THE SMITHSONS WERE OFTEN CONTRADICTORY IN THEIR ARCHITECTURAL DECISIONS, BUILDING BOTH MACHINE-LIKE OBJECTS AND COSY HOUSES. HOW WAS IT POSSIBLE TO FIT DIVERSE FASCINATIONS IN ONE CAREER?

We got to know the owners of the Sugden House, Derek and Jane Sugden. Derek was very candid in the stories he told about commissioning of the house and working with Alison and Peter Smithson. He chose to work with them because he knew them, they’d met through his work as an engineer at Arup’s.

At the time the Smithsons were considered an up-and-coming young practice. I remember he told us that when they presented their first ideas for the project Jane Sugden immediately said there was absolutely no way they were going to have a house with a butterfly shaped roof. They wanted something that would be easier to maintain. They said they were not going to climb up a ladder every autumn to clean the leaves out of the gutter. Alison stormed out of the meeting. She was very upset with any criticism of their work. It was Peter who said: ‘Well, you know, we’ll find a way of responding to your critique. If we can’t design a house for you, then who can we design a house for?’ This anecdote shows their character and their ambition to make radical architecture, but also Peter’s wisdom in elegantly accepting the clients’ criticism and responding to their needs.

SHORTLY AFTER THEY FINISHED THE PROJECT, THEY DID THE HOUSE OF THE FUTURE, SOMETHING TOTALLY DIFFERENT. HAVE YOU ALSO ENGAGED IN EXERCISES OF THIS KIND?

We did work on several commissions which, like the House of the Future, were not intended for a particular site, but had a prototypical character. One was a building that could be used in a garden as a home office, that could be bought and assembled in a garden.

In a similar spirit, we were commissioned a building to accommodate showers and changing facilities for people who cycle to work. We also designed a school building as a kit of elements. We worked on a number of ‘place-less’ projects.

However, a strong aspect of our approach has always been a sense that the place where the work is situated should inform the approach to building. We believe that place should be part of the answer and inform the design. For me, it’s much more interesting to explore possible responses to place. I would also argue that geographical variations are definitely an advantage, rather than a disadvantage. I think familiarity can be stifling, while richness stems from diversity.

WHAT COMPONENT OF THIS HOUSE COULD BE SEEN AS UNIVERSAL, TAKEN OUT OF CONTEXT?

Its simple form, for instance; it’s almost like a child’s drawing of a house . The house is also a prologue to the Smithsons’ description of the simple qualities a house should offer, published in ‘Changing the Art of Inhabitation’ in 1993, which also has a very universal character.

There you can find a series of notes and sketches – made by Alison Smithson, I believe. They talk about what a house should be like. It’s a wonderful sketchy essay on thoughts about inhabiting a house: a creeper growing around a window, the way the light falls on the floor, ways of seeing a view from different positions. It talks about very basic and rather poetic observations about what is important in making a house. Stephen and I found that really touching and certainly very inspiring. It made us re-think our own approach to domesticity.

What I like about the Sugden House is that the Sugdens bought the plot in Watford, which is part of the wider suburban area of greater London, as a young family and built a house with limited means.

It’s a modest house of standard construction, and they lived in it all their lives. In some sense, it’s a beautiful story of a commitment to something that serves simple needs. This is another universal aspect of it, it has nothing to do with composition, but it is closely connected to our attitude to architecture and dwelling in general.

IF I ASK YOU TO THINK ABOUT HOUSES YOU LIKE THAT ARE VERY DIFFERENT FROM THE SUGDEN HOUSE, WHAT COMES TO MIND?

When it comes to concrete examples, I find John Winter’s house in Highgate an amazing building, explicitly connected to his experience of living and working in North America and to Mies van der Rohe’s late work. And I’ve always had an absolute fascination with the work of Konstantinidis, with his almost archaic approach to the making of houses within the Greek landscape. I am also profoundly interested in the houses Siza made at the beginning of his career.

Another house I think is wonderful is Tony Fretton’s Red House, in London… I also stayed at Villa Além, which was built by my friend and colleague, Valerio Olgiati in Alentejo. I think it’s a masterpiece, a wonderful example of domestic architecture. I’m also rather fond of the houses I made for myself – the remodeling of a Georgian house in London, and of a 350-year-old Ticino house in Monte, above Mendrisio.

The lives of houses have always interested me, and I am always stimulated by their stories. In Japan, for example, it is common to make houses that last for the residents’ lifetime and are then demolished. But in Italy, you have grand houses that are passed from generation to generation, to heirs who feel responsible for maintaining their spirit and original grandeur. The way in which diverse cultural and physical conditions affect architecture is, in my opinion, an ever-fascinating field of exploration.

10.08.2021

当斯蒂芬・贝茨(Stephen Bates)和我开始实践时,我们更感兴趣于供给住宅(housing)而不是住宅(houses)本身。我们想制作一种更加集体化的建筑形式,它可以更广泛地服务于社会,而不是狭隘的关注于为单一客户做住宅。

然而,当我想起我们在1996年正式成立公司前一起工作的项目时,首先想到的是为斯蒂芬的一个朋友建造的住宅。他在西班牙南部买了一块令人惊叹的土地,俯瞰着一个山城,可以看到摩洛哥和阿特拉斯山脉的远方。我们在这个项目上紧张地工作了很长时间,但不幸的是,在开工之前,这个项目被取消了。

当时,我们从艾莉森和彼得-史密森(Alison and Peter Smithson)的苏格登之家(Sugden House)得到了很大的启发,这是一个明确的关于平凡的建筑案例。相似的,我们的项目也是对地域主义的探索,某种特定的规范性和平凡性,与场地和传统的和谐。沃特福德这个郊区小住宅,助长了我们对这些主题的兴趣,尽管文脉是如此不同。

你认为苏格登之家是英国50年代中期一个激进的项目吗?

我认为它在概念化平凡的方式上确实很激进。这真的是一个平凡的住宅吗?它的形式可以被看作是非常简单的,几乎是平庸的,由规划法规决定的。但是,开口的安排和与花园有关的外墙的构成——这不是制造窗户的传统方式,对么?

每一个决定都处于有点奇怪的边缘,尽管乍一看,它就像我们在英格兰南部看到的任何一个郊区住宅。作为一个建筑师,你是带着某种创造性的雄心工作的,这真的关乎于你尝试的尺度和规模。

我记得在我们实践的早期,这是一个强烈的启发。我们发现,考虑平凡可以成为一种策略,以应对90年代初英国普遍存在的保守主义。坦率地说,使一些东西看起来不是一个宏大的建筑声明,是一种超越规划部门审查的方式,并允许我们私自裹挟解答和话题,使一切有所不同。当我们在伦敦开发牧羊女大道(Shepherdess Walk)项目时,我记得规划官员相当聪明,他问:"我能不能说明白一点?这是对乔治亚建筑的糟糕复制,还是你的追求背后有其他东西,我们应该谈谈?"我发现这是相当有洞察力的。

最后,尽管这个项目的表现特征是安静而平凡的,但它得到的反应和公众的看法是,它确实有某种程度的不同。我们没能让它变得不可见。

在苏格登之家里,传统的郊区常规布局被混凝土梁的结构方案所解构,创造了一个清晰的主空间。你认为创造这个住宅元素的主要空间是什么?

一楼的灵感来自于北欧建筑——一种对更开放的生活方式的承诺,住宅的不同区域可以更灵活地进行组织。在楼上,它实际上是关于房间和这些房间的比例,作为一个空间的集合。

我认为这两个特点的结合产生了空间上的丰富性,是这座住宅主要的建筑品质。

如果你只看二楼的平面图来判断这个建筑,你不会有所进展。这座住宅必须根据剖面来理解。

让我们来谈谈这座住宅的形象。在这种情况下,开口是按照内部发生的事情,而不是任何强加的秩序。

以其作为郊区住宅的角色来说,它并没有太多矫饰。我发现真正迷人的地方之一是L形的窗户。我经常想知道设计背后的动机是什么。这不仅仅在于构图。我认为有某些兴趣点,是在人物与窗户的关系上。它使住户加倍地接触到花园。L形窗户的直立部分和水平部分以不同的方式与景观相连。这是对比例的有趣探索,也是这个住宅慷慨的证明。它首先是关于内部和外部之间的关系。

还有一个需要注意的非常重要的问题,窗框坐落于墙体厚度之间的关系。在苏格登之家,我们有一个最平庸的解决方案——窗框退进一块砖的厚度。它并没有试图通过将窗子设置在砖的深处来创造一种厚重感,也没有通过将其与外墙面齐平来创造一种抽象感。史密森夫妇的解决方案只是说:"我是一个砖砌的空心墙"——没有任何修辞。它接受了以最直接的方式来描述窗户的真相,以及它与墙体的砌筑的关系。

史密斯夫妇在他们的建筑决定中往往是自相矛盾的,他们既要建造机械般的事物,又要建造舒适的住宅。如何能在一个职业中满足不同的执迷?

我们认识了苏格登之家的主人德里克和简客苏格登(Derek and Jane Sugden)。德里克非常坦诚地讲述了关于房子的委托以及与艾莉森和彼得-史密森合作的故事。他选择与他们合作是因为他认识他们,他们是通过他在奥雅纳(Arup)的工程师工作而认识的。

在当时,史密斯夫妇被认为是一个新兴的年轻事务所。我记得他告诉我们,当他们提出他们对这个项目的第一个想法时,简客苏格登立即说,他们绝对不可能有一个蝴蝶形状的屋顶的房子。他们想要的是更容易维护的东西。他们说,他们不打算每年秋天爬上梯子去清理水沟里的树叶。艾莉森愤怒的离开了会议。她对任何关于他们工作的批评都非常不满。是彼得说:"好吧,你知道,我们会找到一种方法来回应你的批评的。如果我们不能为你们设计住宅,那我们能为谁设计住宅呢?这段轶事显示了他们的性格和做激进建筑的雄心,也显示了彼得优雅地接受客户的批评并回应他们的需求的智慧。

在完成这个项目后不久,他们做了未来之家,完全不同。你是否也参与过这种演练?

我们做了几个委托项目,像未来之家一样,不是为某个特定的地点设计的,而是有一种原型的特征。 其中之一是可以在花园中作为家庭办公室使用的建筑,可以购买并在花园中组装。

本着类似的精神,我们被委托设计一座建筑,为骑自行车上班的人提供淋浴和更衣设施。我们还设计了一个学校建筑,作为一些元素的套件。我们参与了一些 "无场所 "的项目。

然而,一直以来,我们的追求的一个强有力的层面,是感知到项目的所在地应当提示建筑的目的。我们相信,场所应该是解答的一部分,并为设计提供信息。对我来说,探索对场地可能的回应是更有趣味的。我也认同地理差异绝对是优势,而非劣势。我认为熟悉的东西会令人窒息,而丰富则源于多样性。

这所住宅的哪个部分可以被看作是普世的,脱离于文脉的?

例如,它的简单形式;它几乎就像一个孩子画的住宅。这座住宅也是史密斯夫妇在1993年出版的《改变居住的艺术》中对住宅应该提供的简单品质的描述的序幕,它也具有非常普世的特征。

在那里你可以找到一系列的笔记和草图--我相信是由艾莉森-史密森制作的。他们谈到了住宅应该是什么样的。这是一篇精彩的关于居住在住宅里想法的素描文章:窗边的爬山虎,光线落在地板上的方式,从不同位置看风景的方式。它谈到了非常基本和相当有诗意的观察,关于在建造房子时什么是重要的。斯蒂芬和我发现这真的很感人,当然也很有启发性。它使我们重新思考我们自己的家庭生活方式。

我喜欢苏格登之家的原因是,苏格登夫妇作为一个年轻的家庭在沃特福德买下了这块地,这是大伦敦更广阔的郊区的一部分,他们用有限的手段建造了一座住宅。

这是一个标准结构的小住宅,他们在里面生活了一辈子。从某种意义上说,这是一个美丽的故事,是对满足简单需求的东西的承诺。这是它的另一个普世的方面,它与构图无关,但它与我们普遍的对建筑和住所的态度密切相关。

如果我让你想一想你喜欢的、与苏格登住宅非常不同的房子,你会想到什么?

说到具体的例子,我发现约翰-温特(John Winter)在海格特的住宅是一个惊人的建筑,明确地与他在北美的生活和工作经验以及密斯-凡德罗的后期作品有关。我一直对康斯坦丁尼迪斯(Konstantinidis)的作品非常着迷,他在希腊景观中建造住宅的方法几乎是古老的。我也对西扎在其职业生涯开始时制作的住宅深感兴趣。

另一个我觉得很好的住宅,是伦敦的托尼-弗莱顿(Tony Fretton)的红住宅...我还住过阿伦特茹的阿莱姆别墅(Villa Além),那是我的朋友及同事瓦莱里奥-奥尔贾蒂(Valerio Olgiati)建造的。我认为它是一个杰作,是家庭建筑的一个精彩案例。我也相当喜欢我为自己做的住宅——伦敦一栋改造的乔治亚风格的住宅,以及在蒙特的一栋有350年历史的提契诺住宅,在门德里西奥上面。

我一直感兴趣于住宅的生命,总是被它们的故事所激励。例如,在日本,建造一座持续居民的一生,而后被拆毁的住宅很常见。但在意大利,你有宏伟的住宅,它们代代相传,传给那些觉得有责任保持其精神和原始辉煌的继承人。在我看来,不同的文化和物理条件对建筑的影响是一个永远充满魅力的探索领域。

2021年8月10日

ジョナサン・サージソン: ステファン・ベイツと私が事務所を立ち上げたとき、私たちは戸建て住宅よりも集合住宅の方に興味がありました。一人のクライアントのための家をつくるような狭いフォーカスではなく、もっと広く社会へ貢献できるような集合的な建築の形式をつくりたかったのです。

とはいえ、正式に事務所を設立した1996年より以前から彼と一緒に取り組んでいたプロジェクトのことを思い返してみると、最初のプロジェクトは、ステファンの友人の家の計画でした。その友人は、スペインの南部に素晴らしい土地を購入していました。そこからは遠景にモロッコとアトラス山脈を望む丘陵地帯が見渡せました。かなり長い間、力を入れて取り組んでいたのですが、残念ながら、現場に入る直前に中止してしまいました。

当時、私たちは、アリソン&ピーター・スミッソンのサグデン邸に強く影響を受けていたのです。普通であることをはっきりと示した建築の事例ですね。同様に、私たちのプロジェクトも地域性や、ある種の普通さ、平凡さ、土地や伝統との調和を探求するものでした。ワトフォードのこの小さな郊外の住宅は、私たちのこのようなテーマに対する興味を手助けしてくれるものでしたが、お互いのプロジェクトの文脈はかなり異なっていました。

サグデン邸は、50年代半ばのイギリスにとっては、ラディカルなプロジェクトだったと思われますか?

普通であることをコンセプト化した点では、まさにラディカルなものだったと思います。いや、本当に普通の家なのでしょうか?その形はとてもシンプルに見えますし、バナルと言ってもいいですね。地区計画の規制にも従っています。ところが、庭に対する開口部の配列やファサードの構成は、慣習的なやり方ではないですよね?

あらゆるデザイン上の判断が、ちょっと変に感じる境界線上にあるんです。一見すると南イングランドの郊外住宅のように見えるんですけどね。建築家というのは、ある種の創造に対する野心を持って仕事をしているわけですが、それはまさに、寸法とかスケールとかを決めていくことですよね。

このことは建築を始めたばかりのころに強く意識していたことを覚えています。1990年代初めのイギリスでは保守主義の考えが広がり始めていて、それに対抗するために、普通であることを利用していくことは、戦略たり得ると発見したのです。声高な建築的主張がないように見せることは、正直に言って、役所の計画部門の監視をすり抜けていく方法でもありましたし、また、私たちにとっては、差別化を図るための解決策や話題を、密かに運び出していくような方法であったわけです。ロンドンのシェパーデスウォークのプロジェクトを進めているときのことですが、相当頭のきれる計画部門の担当者がいて、こう尋ねてきたことを覚えています。教えていただいても良いでしょうか?これはジョージアン様式の劣化コピーなのでしょうか、それともあなた方のアプローチの背後には何かあって、それについて我々は話し合うべきでしょうか?非常に鋭いと思いましたね。

結局、このプロジェクトの表現上の特徴は、静かで平凡なものであったのに、それに対する反応や大衆からの受け止められ方は実際、何かが違う、といった感じでした。存在を消すことに失敗したんです。

サグデン邸では、伝統的な郊外の規則的な部屋の配置計画が、明快なメインスペースを形成するコンクリート梁の構造的解決によって打ち消されていますよね。この家の空間構成における主な要素は何だとお考えですか?

一階は、スカンジナビアの建築からインスピレーションを得ていますね。家の中の様々な領域をフレキシブルに構成できるような、よりオープンな暮らし方を約束してくれるものです。二階は、まさに部屋、そして空間の集合体としてのこれらの部屋のバランスによって決まっています。

この二つの特徴の組み合わせが空間の豊かさを生み出していますし、この家の主な建築的特質となっていると思います。

一階の平面図だけを見ていては、なかなか理解することはできません。この家は断面で理解する必要があるのです。

この家のイメージについて話をしたいと思います。この家の開口部は、押し付けられた秩序から来ているのではなく、内部で生じる現象に従ったものだと思いますが、どうでしょうか?

郊外の住宅としての役割を自覚しながら、それでいて大きな気負いを感じさせない住宅ですよね。私が特に魅力的だと思うのは、L字型の窓です。そのモチベーションは何だったのだろうかと、よく考えていました。単なる構成というわけではないのです。窓と人の姿がどう関係を持つのか、に対して興味があったのだと思います。住人にとっては、庭に対しての露出が二倍になるわけです。L字型の直立部分と水平部分とでは、風景との繋がり方が違いますよね。プロポーションの面白さの探求の結果でもありますが、この家の寛容さをも示しているのです。第一に重要なことは、内部と外部との関係性ですね。

他に注目すべきは何よりも、窓枠が壁の厚みに対してどう設置されているかです。サグデン邸では最もバナルな解決策が取られています。つまり、レンガ一枚の厚み分だけセットバックしているのです。窓枠を開口部の奥に設置することで重厚感を出そうとしているわけでもなく、また外壁と同一平面上に設置することで抽象化しようとしているわけでもないのです。スミッソン夫妻の解決策は、シンプルにこう言っているのです。穴のあいたレンガ壁ですよ。特別な工夫なんてないですよ、と。そのディテールは、窓の納まり方として、また積層された壁との関わり方として、それが最も素直な方法であることを受け入れているのです。

スミッソン夫妻には、機械のようなオブジェクトと、居心地の良い住宅の両方を作るといった建築的判断における矛盾がしばしば見られると思うのですが、どのようにして、この多様な魅力が一つのキャリアとして成り立っているのでしょうか?

サグデン邸のオーナーである、デレク、そしてジェーン・サグデンと知り合うことができたのですが、デレクは、この家を依頼したこと、アリソン、そしてピーター・スミッソンと一緒に考えてきたことをざっくばらんに語ってくれました。彼は、スミッソン夫妻のことを知っていて、彼らを選んだのです。彼らは、Arupのエンジニアであったデレクの仕事を通して会ったことがあったのです。

当時、スミッソン夫妻は、新進気鋭の若手事務所として認識されていました。デレクが私に教えてくれたことなのですが、スミッソン夫妻が、このプロジェクトの最初のアイデアをプレゼンしたときのことです。ジェーン・サグデンが即座に、バタフライ屋根の家なんて絶対にノー、と言ったそうなのです。彼らはメンテナンスしやすいものが良かったのです。毎年秋になるとハシゴに登って、雨樋の落ち葉を掃除することになるなんて嫌だと言ったのです。アリソンは怒って打ち合わせから飛び出していきました。彼女は、作品を批判されて気が動転していたのです。口火を切ったのは、ピーターでした。こう言ったそうです。「わかりました。あなたの批判にお答えできるよう考えます。あなたのためのデザインができないとしたら、他に誰のためのデザインができましょうか?」この逸話から、彼らの人柄、ラディカルな建築を作るという野心、それに加えて、クライアントの批判を受け止めながら、それに応えようとするピーターの賢明さがうかがえます。

このプロジェクトが終わってすぐに、彼らは全く異なるタイプの「House of the future」プロジェクトを手がけていますね。あなたもこういったタイプの仕事をされたことはあるのでしょうか?

「House of the future」のように特定の敷地を想定せず、プロトタイプ的な質を求めるような依頼はいくつかありました。一つは、ホームオフィスとして庭に設置して使えるようなものです。買ってきて庭で組み立てられるようにしたものです。

同じような考えで、自転車通勤をする人のためのシャワーや更衣室を備えた建物を依頼されたこともあります。エレメントをキット化したような学校を設計したりもしました。数多くの「場所のない」プロジェクトに取り組んできましたね。

ただ、建物は、場所によって特徴づけられるものであるということは、私たちのアプローチ方法としていつも強く意識していることなんです。場所は、答えの一部であって、デザインを特徴づけてくれるものだと信じています。私にとっては、その場所へ応答する可能性を模索する方がはるかに面白いことなのです。それに地理学的な多様性は、デメリットではなくむしろメリットだと思うのです。知りすぎていることは、息苦しくもありますし、多様性から豊かさは生まれるものですから。

この家のどういったところに、コンテクストから自立した普遍性があるのでしょうか?

例えばですが、このシンプルな形。子供の描いた家の絵のようですね。この家は、スミッソン夫妻が1993年に出版した「Changing the Art of Inhabitation」の中で述べている、家が持つべきシンプルな資質に関しての記述で、その序章に使われていて、非常に普遍的な特徴をもっているのです。

そこには、アリソン・スミッソンによるものと思われる一連のメモとスケッチが掲載されています。家とはどうあるべきかが語られています。家に住むことに関する素晴らしい覚え書きです。窓の周りに繁茂するツタ。床にこぼれ落ちる光。さまざまな位置からの景色の見え方。家を作るにあたって何が重要なのか、とても基本的でありながら、詩的な観察が語られています。ステファンと私にとっては、とても感動的で刺激的でした。家庭的なことに対するアプローチを改めて考えさせられました。

サグデン邸で好きなところは、サグデン夫妻が若い家族として、そして限られた資金で、ロンドンの郊外であるワトフォードに土地を買い、家を建てたということなのです。

標準的な作りの質素な家ですが、彼らはそこに生涯住み続けたのです。シンプルな要求に対するひたむきさを感じる美しい話でしょう。これは普遍性に対する別の側面であり、家の構成に関するものとは関係ありません。ただ、建築や住まいに対する一般的な私たちの態度と密接に関係していることです。

サグデン邸とは全く異なる住宅で、好きな住宅といえば、どんな住宅を思い浮かべますか?

具体的な例で言えば、ハイゲイトにある、ジョン・ウィンターの住宅は素晴らしいですね。

彼の北米での生活や仕事の経験、そしてミース・ファン・デル・ローエの晩年の作品との繋がりが明確に見てとれます。コンスタンティニディスの作品は、ギリシャの風景の中に家を建てることに対して、ほとんどアルカイックとも言えるアプローチで、いつも魅了されています。シザが駆け出しの頃に手がけた住宅も、本当に面白いですね。

他に素晴らしい住宅といえば、ロンドンにあるトニー・フレットンのレッドハウス。ヴィラ・アレムにも泊まりましたよ。友人でもあり、同僚でもあるヴァレリオ・オルジアティがアレンテージョに建てた住宅です。マスターピースだと思います。住居建築として素晴らしい事例です。私自身のために作った家もけっこう好きですよ。ロンドンのジョージアンハウスを改装したもの。それと、メンドリジオの近く、モンテにある築350年のティチーノ地方の家を改装したもの。

私は昔から家での暮らしに興味をもっていましたし、そこで起きるそれぞれの物語にはいつも刺激を受けています。例えば、日本では住人が生きている間過ごすためだけに家が作られて、その後は、取り壊されるのが普通ですよね。ところがイタリアでは、代々受け継がれる豪邸があって、その精神や本来もっていた威光を維持していく責任を相続人は感じていたりするわけです。多様な文化的、物理的条件がどのように建築に影響を与えているか考えることは、私にとっては、永遠に魅力的で探求しがいのあることですね。

2021年8月10日

Jonathan Sergison: When Stephen Bates and I set up in practice we were more interested in housing than houses. We wanted to make a more collective form of architecture that could serve society more widely than the narrow focus that comes from making a house for a single client.

And yet, when I think about the projects we worked on together even before we formally established our practice in 1996, one of the first was a house for a friend of Stephen’s. He had bought an amazing piece of land in the south of Spain, overlooking a hill town with distant views of Morocco and the Atlas Mountains. We worked intensely on this project for quite a while, but unfortunately it was cancelled just before going on site.

At the time we were very inspired by Sugden House by Alison and Peter Smithson, an example of architecture that is explicitly about ordinariness. Similarily, our project, was an exploration of regionalism, a certain kind of normality and ordinariness, of harmony with the site and tradition. Our interest in these themes was helped by this little suburban house in Watford even though the context was so different.

DO YOU THINK THE SUDGEN HOUSE WAS A RADICAL PROJECT IN THE MID ‘50S IN ENGLAND?

I think it really was radical in the way it conceptualised ordinariness. Is it really an ordinary house? Its form could be seen as something very simple, almost banal, dictated by planning regulations. But the arrangements of the openings and the composition of the facade in relation to the garden – that’s not a conventional way of making windows, is it?

Every decision is on the edge of being a little bit strange, even though at first glance it looks like any of the suburban houses we see in the south of England. As an architect, you’re working with a certain kind of creative ambition, and it’s really about the measure and scale at which you try things out.

I remember this was a strong inspiration in the early days of our practice. We discovered that playing with ordinariness could be a strategy to deal with the prevailing conservatism that existed in the UK in the early 1990s. To make something look like it’s not a big architectural statement was, frankly, a way of getting past the scrutiny of planning departments and allow us to smuggle solutions and topics that would make a difference. When we developed the project on Shepherdess Walk in London, I remember that the planning officer, who was rather smart, asked: ‘Can I just be clear? Is this a bad copy of Georgian architecture or is there something else behind your approach, that we should talk about?’ I found that rather perceptive.

In the end, even though the representational character of the project was quiet and ordinary, the reception it got and the way it was perceived by the public was, indeed, that it was somehow different. We failed to make it invisible.

IN THE SUGDEN HOUSE, A TRADITIONAL SUBURBAN REGULAR LAYOUT IS DECONSTRUCTED BY A STRUCTURAL SOLUTION OF CONCRETE BEAMS THAT CREATE A CLEAR MAIN SPACE. WHAT DO YOU THINK ARE THE MAIN SPACE-MAKING ELEMENTS OF THE HOUSE?

The ground floor is inspired by Scandinavian architecture - the promise of a more open way of living, where different territories of the house can be more flexibly organised. Upstairs, it is really about rooms and the proportion of these rooms as a collection of spaces.

I think the combination of these two characteristics produces the spatial richness and is the main architectural quality of the house.

If you judged the building by looking at the first-floor plan only, you wouldn’t get very far. This house must be understood in section.

LET’S TALK ABOUT THE IMAGE OF THE HOUSE. IN THIS CASE, THE OPENINGS FOLLOW WHAT HAPPENS INSIDE RATHER THAN ANY IMPOSED ORDER.

Knowing its role as a suburban house, it doesn’t have big pretensions. One of the things I find really fascinating are the L-shaped windows. I’ve often wondered what the motivation was behind the design. It’s more than just composition. I think there’s a certain interest in the way a figure relates to a window. It doubles exposure to the garden for the residents. The upright part of the L-shaped window and the horizontal part connect with the landscape in different ways. It’s an interesting proportion, but also proof of the generosity this house offers. It’s first and foremost about the relationship between inside and outside.

Something else to note is the all-important question of where the window frame sits in relation to the thickness of a wall. In the Sugden House we have the most banal solution - it’s set back by the thickness of a brick. It’s not trying to create a sense of heaviness by setting the window assembly deep within the reveals, nor of abstraction by placing it flush with the outside face. The Smithson’s solution simply says, ‘I’m a brick cavity wall’ - there is no rhetoric. It accepts the truth of the most straightforward way of detailing the window and how it relates to the buildup of the wall.

THE SMITHSONS WERE OFTEN CONTRADICTORY IN THEIR ARCHITECTURAL DECISIONS, BUILDING BOTH MACHINE-LIKE OBJECTS AND COSY HOUSES. HOW WAS IT POSSIBLE TO FIT DIVERSE FASCINATIONS IN ONE CAREER?

We got to know the owners of the Sugden House, Derek and Jane Sugden. Derek was very candid in the stories he told about commissioning of the house and working with Alison and Peter Smithson. He chose to work with them because he knew them, they’d met through his work as an engineer at Arup’s.

At the time the Smithsons were considered an up-and-coming young practice. I remember he told us that when they presented their first ideas for the project Jane Sugden immediately said there was absolutely no way they were going to have a house with a butterfly shaped roof. They wanted something that would be easier to maintain. They said they were not going to climb up a ladder every autumn to clean the leaves out of the gutter. Alison stormed out of the meeting. She was very upset with any criticism of their work. It was Peter who said: ‘Well, you know, we’ll find a way of responding to your critique. If we can’t design a house for you, then who can we design a house for?’ This anecdote shows their character and their ambition to make radical architecture, but also Peter’s wisdom in elegantly accepting the clients’ criticism and responding to their needs.

SHORTLY AFTER THEY FINISHED THE PROJECT, THEY DID THE HOUSE OF THE FUTURE, SOMETHING TOTALLY DIFFERENT. HAVE YOU ALSO ENGAGED IN EXERCISES OF THIS KIND?

We did work on several commissions which, like the House of the Future, were not intended for a particular site, but had a prototypical character. One was a building that could be used in a garden as a home office, that could be bought and assembled in a garden.

In a similar spirit, we were commissioned a building to accommodate showers and changing facilities for people who cycle to work. We also designed a school building as a kit of elements. We worked on a number of ‘place-less’ projects.

However, a strong aspect of our approach has always been a sense that the place where the work is situated should inform the approach to building. We believe that place should be part of the answer and inform the design. For me, it’s much more interesting to explore possible responses to place. I would also argue that geographical variations are definitely an advantage, rather than a disadvantage. I think familiarity can be stifling, while richness stems from diversity.

WHAT COMPONENT OF THIS HOUSE COULD BE SEEN AS UNIVERSAL, TAKEN OUT OF CONTEXT?

Its simple form, for instance; it’s almost like a child’s drawing of a house . The house is also a prologue to the Smithsons’ description of the simple qualities a house should offer, published in ‘Changing the Art of Inhabitation’ in 1993, which also has a very universal character.

There you can find a series of notes and sketches – made by Alison Smithson, I believe. They talk about what a house should be like. It’s a wonderful sketchy essay on thoughts about inhabiting a house: a creeper growing around a window, the way the light falls on the floor, ways of seeing a view from different positions. It talks about very basic and rather poetic observations about what is important in making a house. Stephen and I found that really touching and certainly very inspiring. It made us re-think our own approach to domesticity.

What I like about the Sugden House is that the Sugdens bought the plot in Watford, which is part of the wider suburban area of greater London, as a young family and built a house with limited means.

It’s a modest house of standard construction, and they lived in it all their lives. In some sense, it’s a beautiful story of a commitment to something that serves simple needs. This is another universal aspect of it, it has nothing to do with composition, but it is closely connected to our attitude to architecture and dwelling in general.

IF I ASK YOU TO THINK ABOUT HOUSES YOU LIKE THAT ARE VERY DIFFERENT FROM THE SUGDEN HOUSE, WHAT COMES TO MIND?

When it comes to concrete examples, I find John Winter’s house in Highgate an amazing building, explicitly connected to his experience of living and working in North America and to Mies van der Rohe’s late work. And I’ve always had an absolute fascination with the work of Konstantinidis, with his almost archaic approach to the making of houses within the Greek landscape. I am also profoundly interested in the houses Siza made at the beginning of his career.

Another house I think is wonderful is Tony Fretton’s Red House, in London… I also stayed at Villa Além, which was built by my friend and colleague, Valerio Olgiati in Alentejo. I think it’s a masterpiece, a wonderful example of domestic architecture. I’m also rather fond of the houses I made for myself – the remodeling of a Georgian house in London, and of a 350-year-old Ticino house in Monte, above Mendrisio.

The lives of houses have always interested me, and I am always stimulated by their stories. In Japan, for example, it is common to make houses that last for the residents’ lifetime and are then demolished. But in Italy, you have grand houses that are passed from generation to generation, to heirs who feel responsible for maintaining their spirit and original grandeur. The way in which diverse cultural and physical conditions affect architecture is, in my opinion, an ever-fascinating field of exploration.

10.08.2021

当斯蒂芬・贝茨(Stephen Bates)和我开始实践时,我们更感兴趣于供给住宅(housing)而不是住宅(houses)本身。我们想制作一种更加集体化的建筑形式,它可以更广泛地服务于社会,而不是狭隘的关注于为单一客户做住宅。

然而,当我想起我们在1996年正式成立公司前一起工作的项目时,首先想到的是为斯蒂芬的一个朋友建造的住宅。他在西班牙南部买了一块令人惊叹的土地,俯瞰着一个山城,可以看到摩洛哥和阿特拉斯山脉的远方。我们在这个项目上紧张地工作了很长时间,但不幸的是,在开工之前,这个项目被取消了。

当时,我们从艾莉森和彼得-史密森(Alison and Peter Smithson)的苏格登之家(Sugden House)得到了很大的启发,这是一个明确的关于平凡的建筑案例。相似的,我们的项目也是对地域主义的探索,某种特定的规范性和平凡性,与场地和传统的和谐。沃特福德这个郊区小住宅,助长了我们对这些主题的兴趣,尽管文脉是如此不同。

你认为苏格登之家是英国50年代中期一个激进的项目吗?

我认为它在概念化平凡的方式上确实很激进。这真的是一个平凡的住宅吗?它的形式可以被看作是非常简单的,几乎是平庸的,由规划法规决定的。但是,开口的安排和与花园有关的外墙的构成——这不是制造窗户的传统方式,对么?

每一个决定都处于有点奇怪的边缘,尽管乍一看,它就像我们在英格兰南部看到的任何一个郊区住宅。作为一个建筑师,你是带着某种创造性的雄心工作的,这真的关乎于你尝试的尺度和规模。

我记得在我们实践的早期,这是一个强烈的启发。我们发现,考虑平凡可以成为一种策略,以应对90年代初英国普遍存在的保守主义。坦率地说,使一些东西看起来不是一个宏大的建筑声明,是一种超越规划部门审查的方式,并允许我们私自裹挟解答和话题,使一切有所不同。当我们在伦敦开发牧羊女大道(Shepherdess Walk)项目时,我记得规划官员相当聪明,他问:"我能不能说明白一点?这是对乔治亚建筑的糟糕复制,还是你的追求背后有其他东西,我们应该谈谈?"我发现这是相当有洞察力的。

最后,尽管这个项目的表现特征是安静而平凡的,但它得到的反应和公众的看法是,它确实有某种程度的不同。我们没能让它变得不可见。

在苏格登之家里,传统的郊区常规布局被混凝土梁的结构方案所解构,创造了一个清晰的主空间。你认为创造这个住宅元素的主要空间是什么?

一楼的灵感来自于北欧建筑——一种对更开放的生活方式的承诺,住宅的不同区域可以更灵活地进行组织。在楼上,它实际上是关于房间和这些房间的比例,作为一个空间的集合。

我认为这两个特点的结合产生了空间上的丰富性,是这座住宅主要的建筑品质。

如果你只看二楼的平面图来判断这个建筑,你不会有所进展。这座住宅必须根据剖面来理解。

让我们来谈谈这座住宅的形象。在这种情况下,开口是按照内部发生的事情,而不是任何强加的秩序。

以其作为郊区住宅的角色来说,它并没有太多矫饰。我发现真正迷人的地方之一是L形的窗户。我经常想知道设计背后的动机是什么。这不仅仅在于构图。我认为有某些兴趣点,是在人物与窗户的关系上。它使住户加倍地接触到花园。L形窗户的直立部分和水平部分以不同的方式与景观相连。这是对比例的有趣探索,也是这个住宅慷慨的证明。它首先是关于内部和外部之间的关系。

还有一个需要注意的非常重要的问题,窗框坐落于墙体厚度之间的关系。在苏格登之家,我们有一个最平庸的解决方案——窗框退进一块砖的厚度。它并没有试图通过将窗子设置在砖的深处来创造一种厚重感,也没有通过将其与外墙面齐平来创造一种抽象感。史密森夫妇的解决方案只是说:"我是一个砖砌的空心墙"——没有任何修辞。它接受了以最直接的方式来描述窗户的真相,以及它与墙体的砌筑的关系。

史密斯夫妇在他们的建筑决定中往往是自相矛盾的,他们既要建造机械般的事物,又要建造舒适的住宅。如何能在一个职业中满足不同的执迷?

我们认识了苏格登之家的主人德里克和简客苏格登(Derek and Jane Sugden)。德里克非常坦诚地讲述了关于房子的委托以及与艾莉森和彼得-史密森合作的故事。他选择与他们合作是因为他认识他们,他们是通过他在奥雅纳(Arup)的工程师工作而认识的。

在当时,史密斯夫妇被认为是一个新兴的年轻事务所。我记得他告诉我们,当他们提出他们对这个项目的第一个想法时,简客苏格登立即说,他们绝对不可能有一个蝴蝶形状的屋顶的房子。他们想要的是更容易维护的东西。他们说,他们不打算每年秋天爬上梯子去清理水沟里的树叶。艾莉森愤怒的离开了会议。她对任何关于他们工作的批评都非常不满。是彼得说:"好吧,你知道,我们会找到一种方法来回应你的批评的。如果我们不能为你们设计住宅,那我们能为谁设计住宅呢?这段轶事显示了他们的性格和做激进建筑的雄心,也显示了彼得优雅地接受客户的批评并回应他们的需求的智慧。

在完成这个项目后不久,他们做了未来之家,完全不同。你是否也参与过这种演练?

我们做了几个委托项目,像未来之家一样,不是为某个特定的地点设计的,而是有一种原型的特征。 其中之一是可以在花园中作为家庭办公室使用的建筑,可以购买并在花园中组装。

本着类似的精神,我们被委托设计一座建筑,为骑自行车上班的人提供淋浴和更衣设施。我们还设计了一个学校建筑,作为一些元素的套件。我们参与了一些 "无场所 "的项目。

然而,一直以来,我们的追求的一个强有力的层面,是感知到项目的所在地应当提示建筑的目的。我们相信,场所应该是解答的一部分,并为设计提供信息。对我来说,探索对场地可能的回应是更有趣味的。我也认同地理差异绝对是优势,而非劣势。我认为熟悉的东西会令人窒息,而丰富则源于多样性。

这所住宅的哪个部分可以被看作是普世的,脱离于文脉的?

例如,它的简单形式;它几乎就像一个孩子画的住宅。这座住宅也是史密斯夫妇在1993年出版的《改变居住的艺术》中对住宅应该提供的简单品质的描述的序幕,它也具有非常普世的特征。

在那里你可以找到一系列的笔记和草图--我相信是由艾莉森-史密森制作的。他们谈到了住宅应该是什么样的。这是一篇精彩的关于居住在住宅里想法的素描文章:窗边的爬山虎,光线落在地板上的方式,从不同位置看风景的方式。它谈到了非常基本和相当有诗意的观察,关于在建造房子时什么是重要的。斯蒂芬和我发现这真的很感人,当然也很有启发性。它使我们重新思考我们自己的家庭生活方式。

我喜欢苏格登之家的原因是,苏格登夫妇作为一个年轻的家庭在沃特福德买下了这块地,这是大伦敦更广阔的郊区的一部分,他们用有限的手段建造了一座住宅。

这是一个标准结构的小住宅,他们在里面生活了一辈子。从某种意义上说,这是一个美丽的故事,是对满足简单需求的东西的承诺。这是它的另一个普世的方面,它与构图无关,但它与我们普遍的对建筑和住所的态度密切相关。

如果我让你想一想你喜欢的、与苏格登住宅非常不同的房子,你会想到什么?

说到具体的例子,我发现约翰-温特(John Winter)在海格特的住宅是一个惊人的建筑,明确地与他在北美的生活和工作经验以及密斯-凡德罗的后期作品有关。我一直对康斯坦丁尼迪斯(Konstantinidis)的作品非常着迷,他在希腊景观中建造住宅的方法几乎是古老的。我也对西扎在其职业生涯开始时制作的住宅深感兴趣。

另一个我觉得很好的住宅,是伦敦的托尼-弗莱顿(Tony Fretton)的红住宅...我还住过阿伦特茹的阿莱姆别墅(Villa Além),那是我的朋友及同事瓦莱里奥-奥尔贾蒂(Valerio Olgiati)建造的。我认为它是一个杰作,是家庭建筑的一个精彩案例。我也相当喜欢我为自己做的住宅——伦敦一栋改造的乔治亚风格的住宅,以及在蒙特的一栋有350年历史的提契诺住宅,在门德里西奥上面。

我一直感兴趣于住宅的生命,总是被它们的故事所激励。例如,在日本,建造一座持续居民的一生,而后被拆毁的住宅很常见。但在意大利,你有宏伟的住宅,它们代代相传,传给那些觉得有责任保持其精神和原始辉煌的继承人。在我看来,不同的文化和物理条件对建筑的影响是一个永远充满魅力的探索领域。

2021年8月10日

Jonathan Sergison

Jonathan Sergison graduated from the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1989 and gained professional experience working for David Chipperfield and Tony Fretton

Jonathan Sergison and Stephen Bates founded Sergison Bates architects in London in 1996, and in 2010 a second studio was opened in Zurich Switzerland. Sergison Bates architects have built numerous projects worldwide and the practice has received many prizes and awards. The work of Sergison Bates architects has been extensively published.

Jonathan Sergison has taught at a number of schools of architecture, including the University of North London, the Architectural Association in London, was Visiting Professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne (EPFL), the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Since 2008 he has been Professor of Design and Construction at the Accademia di Mendrisio, Switzerland.

He is particularly interested in urban questions and the conditions of the contemporary European city. More specifically he has addressed through writing, teaching and practice the role housing might play in this changing context.

He regularly writes and lectures, attends reviews in schools of architecture and is actively involved in commissions and competition juries.

Jonathan Sergison

Jonathan Sergison graduated from the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1989 and gained professional experience working for David Chipperfield and Tony Fretton

Jonathan Sergison and Stephen Bates founded Sergison Bates architects in London in 1996, and in 2010 a second studio was opened in Zurich Switzerland. Sergison Bates architects have built numerous projects worldwide and the practice has received many prizes and awards. The work of Sergison Bates architects has been extensively published.

Jonathan Sergison has taught at a number of schools of architecture, including the University of North London, the Architectural Association in London, was Visiting Professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne (EPFL), the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Since 2008 he has been Professor of Design and Construction at the Accademia di Mendrisio, Switzerland.

He is particularly interested in urban questions and the conditions of the contemporary European city. More specifically he has addressed through writing, teaching and practice the role housing might play in this changing context.

He regularly writes and lectures, attends reviews in schools of architecture and is actively involved in commissions and competition juries.

Jonathan Sergison

Jonathan Sergison graduated from the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1989 and gained professional experience working for David Chipperfield and Tony Fretton

Jonathan Sergison and Stephen Bates founded Sergison Bates architects in London in 1996, and in 2010 a second studio was opened in Zurich Switzerland. Sergison Bates architects have built numerous projects worldwide and the practice has received many prizes and awards. The work of Sergison Bates architects has been extensively published.

Jonathan Sergison has taught at a number of schools of architecture, including the University of North London, the Architectural Association in London, was Visiting Professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne (EPFL), the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Since 2008 he has been Professor of Design and Construction at the Accademia di Mendrisio, Switzerland.

He is particularly interested in urban questions and the conditions of the contemporary European city. More specifically he has addressed through writing, teaching and practice the role housing might play in this changing context.

He regularly writes and lectures, attends reviews in schools of architecture and is actively involved in commissions and competition juries.