バルナバス・カルダー:モダニズムは、基本的に化石燃料を盛大に消費することで生まれた建築です。ですから、この気候危機の最中にある建築に対して、モダニズムが教えてくれることは、ほぼ完璧に間違っているということです。モダニズムにおける素材、サービス、それに輸送に対する態度は、大きく見て生態学的危機と並行しているものです。

私は、私の専門である建築教育が、モダニズムを標榜し続けていることに深い懸念を抱いています。それは、建築の外観や素材、機能を学ぼうとする学生や実務者に向けてのポジティブで直接的な教訓として理解されてしまっているわけですから。

サヴォア邸はタイムレスなものでしょうか?

30年後、いや10年後にはその質問が大笑いされるものになることを願っていますよ。タイムレスなものだとは全く思いませんね。私たちがまだその時代にいるからそう感じるのであって、本質的にタイムレスな何かがあるわけではなく、私たちがそこから進歩していないだけでしょう。現代的だと感じてしまうのは、私たちがその真似をしていて、化石燃料を狂ったようにばら撒いていたその時代から、技術的、あるいは理論的に派生した世界に私たちがいるからなのでしょう。私たちは未だに化石燃料と共依存の関係にありますし、建設業界のあらゆる分野では、可能な限り熱を労働力に変えようとしているのです。

サヴォア邸は、今もなお私たちの望む近代的なライフスタイルを象徴するものなのでしょうか?

サヴォア邸は、化石燃料を燃やすための機械なのだと言いたいです。それは現場でも遠隔地でも同じことです。特に遠隔地におけるそれは、1920年代には珍しいことでした。初期モダニズムの素晴らしさの一つは、薪や石炭などのメンテナンスやその面倒をなくしたことなのでしょう。薪を取り替えたりするのは、つまらなく、手の汚れる仕事でしたから。モダニストたちは、その仕事を石油を燃料とするボイラー、電気暖房、照明へと置き換えようとしていたのです。使用人が石炭の入ったバケツを持ってくるよりも清潔で、スイッチを押すだけの、ほとんど魔法のようなものですからね。

サヴォア邸は、新しく強力なエネルギー技術が生活や建築に何をもたらすのか、を探求したル・コルビュジエの一連の取り組みの中では、その後期に位置付けられるものだと思います。「住宅は住むための機械である」は多くの議論を生みましたが、その意味することは明確だと思います。つまり、機械が化石燃料のエネルギーを工業生産へと変換するように、住宅、いや住むためのそれは、化石燃料のエネルギーをライススタイルへと変換したのです。

「モダン」ライフスタイルは、大量生産から生まれたものですよね。サヴォア邸は、それが建設される直前の数年間に起こった二つの革命、つまり、内燃エンジンと集中型発電の遠隔地への配電技術に依存しながら、それらを褒めたたえているわけです。これら二つの技術があったからこそ、そのヴィラはパリから20キロも離れた場所にあるのでしょう。

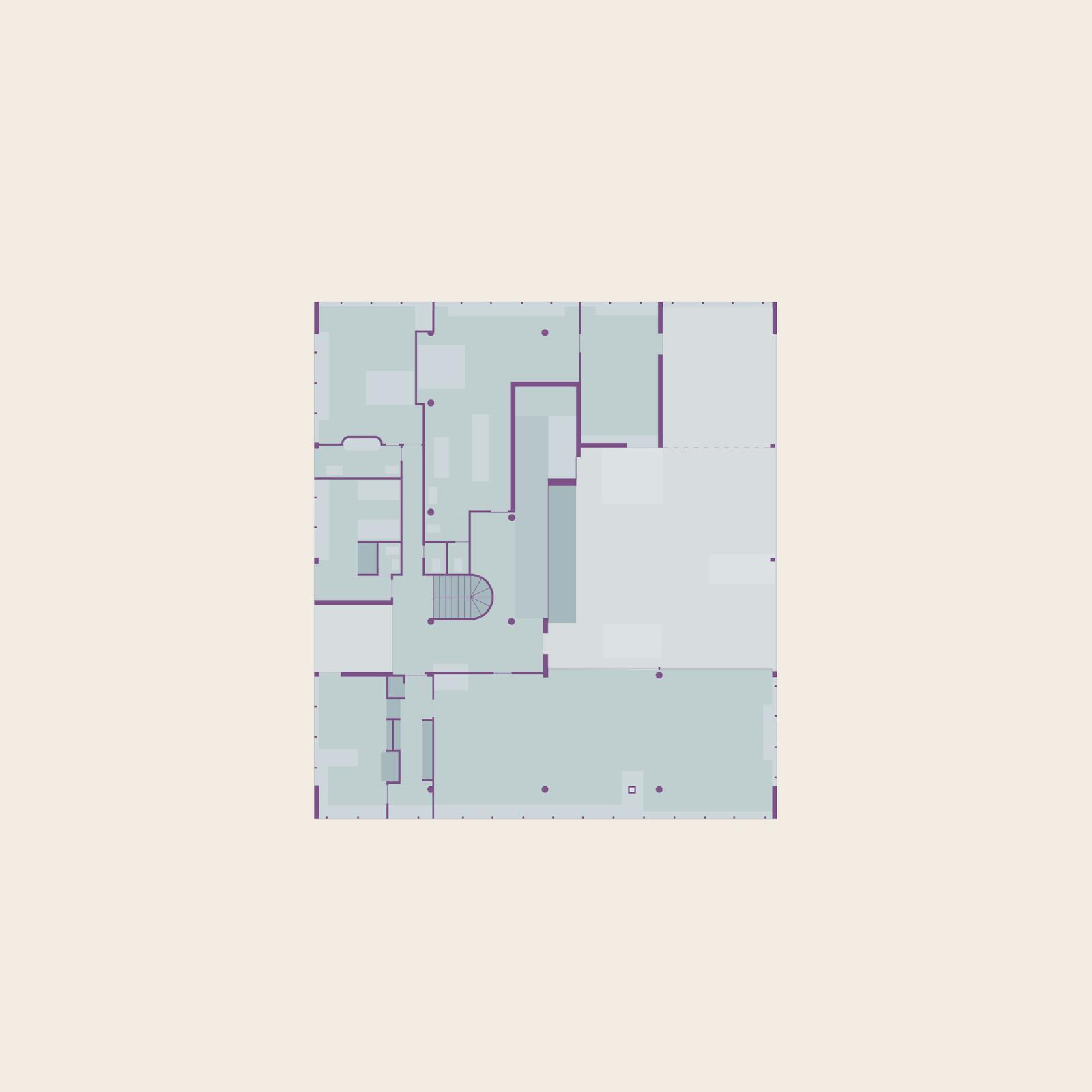

自家用車のおかげで富裕層は、週末にでもさっとパリから抜け出る事が可能になったわけですし、ご存知のように、この建物の地上階平面図は車が旋回することを賞賛しているのです。初期の案では、家全体を貫くスロープを登って、車を上方に駐車することまで提案していました。

この建物は電気の建物でもあるのです。当初、彼はこの建物を電気で暖めようと熱心に取り組んでいたのですが、必要なエネルギーを得るのには、この家のためだけに特別な変圧装置が必要でしたし、それはこの裕福なクライアントにとっても予算内で収まるものではありませんでした。

もちろん、素材も化石燃料の革命によるものです。つまり、熱に強いものです。ル・コルビュジエはその著書の中で、自然素材は使いたくないと明確に述べています。彼の提唱する「工業材料」とは、化石燃料の高熱を大量に使用し、加工された材料のことです。コンクリートを繋げるためのセメントも、それを補強するための鋼鉄も、本来は何千年の人類の歴史において知られていたものではありますが。それがこれほど大量に使われるようになったのも、19世紀の後半の安価な化石燃料による熱が豊富に利用できるようになってからです。

その結果がデザインに直接的に表れている、と。

その通り!巨大な窓や、体積に不釣り合いなほどの表面積の割合は、化石燃料の熱の賜物ですよ。産業革命以前、つまり、化石燃料の使用される以前の窓を見てみると、ガラスはとても小さく、たいてい凸凹がついていますよね。それがこの時代になると、サロンからセントラルバルコニーへ、そしてサンテラスへと出るための巨大なガラスへと変わっていきます。

これらのガラス板はとてつもなく大きいものですが、それが可動式ドアに使われていたりするのです。石炭や石油によって安価な熱を得ることができたからこそ可能になったガラスの技術です。つまり、建築の素材はその生産に膨大な熱を必要とするわけですが、その素材が近代建築の5原則、ピロティ、自由な平面、自由な立面、水平連続窓、屋上庭園を作り上げたのでしょう。

自由な平面は、コンクリートと鉄のおかげで可能になるもので、垂直の壁は力学的には、もはや何の働きもしないということですよね。自由な立面は、同じことを少し違う言い方で言っているだけですね。ピロティもまた、同じことを少し違う言い方にしているだけなのですが、これらの自由さがもたらすのは、ほとんど全ての壁、天井、床が外壁面となる建物の生産なのです。

ある部屋から別の部屋へと熱が漏れていくといったことすらもなく、それなのに、外壁は全く断熱のされていない(されていたとしてもごく僅かに)単層のコンクリートや鉄骨なのです。ですから、建物は連続的で巨大なコールドブリッジとなるのです。

これは初期モダニズム建築にとっては、偶然ではなく必然のことです。安価なエネルギーは、その場所が寒かろうが暑かろうが、建築をこれまでのあり方から自由にしてくれるのです。この100年間における設計の多くは、化石燃料を莫大に投入するという代償を支払うことで、前の世代が実践してきた賢明で本質的な慣習に反旗を翻してきたのです。

歴史的を遡ると、寒冷地では、熱源を共有するためにも部屋をその周囲に集めることで、できる限りジュールを節約していましたし、建築家は体積に対する表面積の割合を最小限に抑えようとしていました。ところが、初期モダニズムのヴィラではそれが逆転しているのです。設計者たちは、膨大な表面積を抱えながらも屋内と屋外を隔てる障壁を極限まで小さくすることにすっかり興奮してしまったのです。彼らは、この障壁の破壊を概念的で視覚的なことのように捉えているようですが、実際、それは安価な暖房のおかげで可能になっていることなのです。このような大きく解放的な部屋は、複数階の連続した空間を一体化させたりするのですが、それも強力なセントラルヒーティングがなければ、隙間風が吹き込んで住み心地が悪いものになってしまいます。

それは権力、あるいは支配の象徴でもあったのでしょうか?

はい。初期モダニズムには、自然に対する人間の勝利という非常に強い精神があったのだと思います。サヴォア邸はまさにそのカテゴリーに入ります。

ただ結局は、傲慢だったということなのでしょう。私たちの今の状況もそうですが、私たちは自然の一部であって、それを支配するものではない。サヴォア邸をミクロなスケールで見てみると、ル・コルビュジエの自然を征服したいという要求が、そのインスピレーションのもととなったテクノロジーの能力を越えてしまったのだと思います。だからそれは、住むための機械とはならなかった。

この設計に必要とされた熱の入力レベルは、建物の湿気で健康を害した息子のいる裕福な家族でさえも維持できるレベルを超えてしまっていました。

あなたは、これからの生活を支えていくためにも、これまでの歴史の中で開発されてきた技術やエネルギーの生産体制におけるある決定論を模索しているのではないかと、あなたの本(ARCHITECTURE, FROM PREHISTORY TO CLIMATE EMERGENCY, PELICAN 2022) を読んで感じました。エネルギー以外の点で、この家を他の家と区別する要因、あるいは無駄だと考えられるものは何があるのか、お聞きしたいです。

私が決定論を探しているように見えるということですが、私はあの本の中でシンプルな問いに答える以外のことを求めていたわけではありません。その問いはつまり、「エネルギーの使用と建築への私たちの関心は、振り返って考えるとどのようなものであったのか?」と。それはさらに「エネルギーの使用と建築との関係とは?」という問いにつながるわけですが、その答えは、建築とエネルギーとは常に切っても切れない関係にある、というものでしたし、そのことは何度も戻ってくるものなのです。何度も何度も、本当に何度も。イヌイットの住居の季節性、古代遺跡のエネルギー基盤、ジョージアン様式の住宅の窓、そしてル・コルビュジエのヴィラ、そして気候変動という非常事態に至るまでのさまざまな文脈において、そうなのです。

ル・コルビュジエのサヴォア邸が、こうしたケーススタディに適しているのは、ル・コルビュジエがまだ初期段階であった技術的変化を察知して、自身の建築を素早く再構築することに驚くほど長けていたからです。それは、数世代にわたってエネルギーの変遷を経験した過去の建築への伝統主義的な言及を求められる面倒がなくなったことを意味します。それは例を出すと、エドウィン・ラッチェンスの建物なのですが。それも同時代のことですよ。

それもまた、ル・コルビュジエと同じように自動車やセントラルヒーティング、資材の容易な運搬、コンクリートやアスファルト、その他の類似技術を中心に考えられた建物であることには変わりないのですが。それらは何百年、何千年の歴史を持つ建築の複雑な美学的議論にも参与しているわけですし、その結果、すさまじいほどの注釈がつけられているのです。

ル・コルビュジエの場合は、非常に冷酷で、鋭く素早く、そして分析は簡潔で明瞭なわけですから。

もう少し芸術的な視点から、建築家として、あるいは建築に意識的な一人の人間として、その場に建ったときの印象を教えてください。その建築には、どのような客観的、物質的、理論的な質があるのだとお考えですか?倫理的な疑念に打ち勝つほどの全体性がもたらす効果がありましたか?

私にとって、偉大なモダニストたちから得られるとても良い点は、彼らの物事を深く捉え直そうとする意欲と、思いもよらないところから影響を受けとろうとする姿勢です。彼らは、技術的な条件が類似しているという理由から、他のモチーフをコピーするといったことはせずに、正しい情報を用いてデザインするという意味で、技術的なデータを十分に把握する能力を持っていました。

サヴォア邸を訪れた際の美的な、あるいは知的な体験に関してですね。皆さんにはその時々の状況に応じて総合的に再考する方法を学んで欲しいと考えています。プロジェクトとしてのそれは、素晴らしく傑出したものですよ。だからこそ、それを深く再考することが、今、私たちがこのプロジェクトから得られることなのです。単に素材やモチーフ、といったことではなく。

私たちの直面している課題は、初期モダニストたちのそれよりもさらに大きくエキサイティングなものです。彼らは、化石燃料主義の中で転換を強いられただけですが、私たちには、それに変わる新しい建築を見つける必要があるのです。

それはより大きな転換となるでしょう。例えばですが、天候によって増減する再生可能エネルギーによる電力供給の不安定さを内包する建築文化を受け入れ始めることなのかもしれません。再生可能エネルギーは本来、断続的なものですから。私たちの生活と建物を再生可能エネルギーのシステムの一部として再設計することは、ル・コルビュジエのチームの助けとともに解決すべき課題です。

初めてサヴォア邸を訪れたとき、とても美しく魅力的なものだと感じました。ただ、一世紀近くにわたって車を中心とする都市が発展したおかげで、田園地帯の雄大で開放的な景色はとうの昔に消え去り、今は生垣に囲まれた郊外になってしまっていることには、がっかりしました。当時の最先端の化石燃料を使った贅沢品が、これほどまで魅力的でカリスマ的なものになっているその理由を知っている今では、私は自身の喜びが薄れていくことに気づいてしまいました。

家に着くとすぐに手が洗えて、サーキュレーションシステムも二つあって、そのどちらかを選んで登っていき、広いテラスに横たわれる。そういった、ある種の自由がこの建築にはあるのだと思いますが、私たちにこうした喜びを追及するための自由は許されるのでしょうか?

サーキュレーションシステムが二つあることは浪費ですから、浪費はやめないといけませんね。戸建て住宅なら一つで十分でしょう。建設するのにエネルギーも二酸化炭素排出量も増えて、暖房費もかかるわけですから、全く必要ないものです。そうすれば二酸化炭素排出量も減りますし、その分を輸送に使えます。

サヴォア邸は、とてつもなく広大なもので、屋上に座って日光浴をしたり、内部のオープンスペースから別の景色を眺めるといった、楽しみのためだけに作られた全く新しいタイプの空間を作り出しています。建物自体もオープンスペースに囲まれているのであれば、さらに素晴らしいものになるとは思いますが、それはまた、炭素排出量を増やして買うような贅沢品なのです。

それは、気候変動という緊急時に考えるようなラグジュアリーではなく、私たちが求めるべきは、暖かな隠れ家のようなラグジュアリーなのです。

イギリスの冬は、寒く湿気も多いです。私は、今夜も変わらず、炭素排出量が多く、高価な天然ガスのセントラルヒーティングしかないこの家に座っているのですが、その設定温度はとても低く設定したり、あるいはオフにしているのです。ですから、私は、保温性のあるワンジーを着て、スカーフを巻いているのですが。セントラルヒーティングが導入される以前のように、小さくて暖かなプールがあって、そこに近づいたりして距離を選べることができたら、どんなにいいだろうと考えるわけです。

『Thermal delight』(Thermal delight in Architecture, Lisa Heschong, MIT 1979)は、モダニストたちが私たちの上に塗りつぶしたベージュ色の(均一な)熱とは全く異なる考え方です。建物に入るときの経験について聞いているのでしたね。もちろん建築的プロムナードの考えには私も大賛成です。ただ、真にサスティナブルな戸建て住宅の建築的プロムナードは多分もっと短いものですよね。もっと小さいものになるでしょうから。化石燃料と住宅との関係において重要な特徴の一つは、大きな建物を安く建てることでした。ですから、農業時代の非エリート階級の住宅を見てみると、現在の世界人口における同程度の富の人々の住宅よりもかなり小さいのです。

低炭素住宅が小さいものであれば、その中を散歩(プロムナード)することも少なくなります。だからといって、設計者が建物の外から中へと移動する体験に対して繊細な感性を持たず、興味がないということでもないのですが。それは熱的な面でも光的な面でもそうです。優れたパッシブ・サーマル・デザインは、とても豊かな建築的、美的体験となり得るものです。寒冷地ではできる限りの日射熱を集め、温暖なところでは日射熱を遮断するのです。

中層の低炭素建築も建築デザイナーにとってはスリリングな挑戦になるでしょう。低炭素であることが、エレガントで思慮深いプランニングや、建物間あるいは住戸間を相合に暖房する方法を見つけるきっかけとなるでしょうし、建築的思想や美的経験を非常に豊かにしてくれる領域なのだと思います。しかし、その美的経験は、視覚的に華やかなものではなく、20世紀や21世紀初頭に過度な優遇を受けてきたような即座に写真映えするものではないでしょう。それは温熱的な経験によるものですし、雑誌やウェブサイトでは伝えるのが本当に難しいものだと思います。ですから、建築の出版業界からは、常に差別されるようなものになるのかもしれませんが。ですが、エネルギー消費量が少なく温度調整に優れた住宅に住むという体験の中では、温熱的な喜びの方がはるかに重要なことです。多くの研究が示すように、健康や幸福、ウェルビーイングにとっては、視覚的なものよりも温熱的なものの方がはるかに重要なのです。

温熱的に快適であることは、大きな喜びです。季節ごとに異なる喜びを味わえるのです。冬には、本当に寒い日がやって来ると、家の居心地の良さを実感しますし、夏には、外が焼けつくような暑さでも、家の中が涼しいと、この上なく幸せを感じます。こうした喜びは決して古びることありません。最高の景色は、時の経過と慣習によって、その魅力が失われていくものですが。温熱的な喜びは、時代を超えて建築の絶対的な核をなす優先事項です。人口の5%程度の富裕層以外の人々にとっては、建物がどう見えるかよりもずっと重要な関心事であったのです。それに、たとえ非常に強力な権力を持っている人でも、温熱環境は不可欠なものでした。ルイ14世の寝室は、ヴェルサイユ宮殿の中心にあって、そこにはとんでもなく壮大な装飾が施されているのですが、その部屋のサイズは、宮殿内のどの部屋よりも小さいのです。暖炉で暖めて過ごすには、十分な小ささです。

ル・コルビュジエは、リデュース、リユース、リサイクルの考えについて、どう捉えていたと思いますか?

ル・コルビュジエは、白のヴィラの時代において、パティーナとパリンプセトという古くからの建築の楽しみに対抗したわけですよね。サヴォア邸においては全てが真新しく見えるように設計しました。1935年ごろより前に作られた彼の作品は、少しでも古びて見えるものは失敗作として、取り替える必要があったのです。多くの建築家は、いまだに新しさを保つという理想にとらわれています。

そうではない方法もあって、日本の伝統的な景観は、苔がゆっくりと成長することや、水が壁を流れ落ち、その跡が残ってしまうことを賞賛しています。それは移り変わるものへの賛美であって、変わらないものへのそれではなく、長い時間のあとで表れる、ある種の優美さのことなのです。それは、多くの現代建築が苦手としていることです。建物は、完成後にはできるだけ早く、完璧なオブジェとして撮影されるのですから。

新しいものやピカピカなものへの崇拝は、生物学的には破滅的なものなのです。気候変動という非常事態の中で、新品でまっさらなもので満たされた家や部屋を見せつけることなど、社会的に恥ずべきことなのです。良い趣味や良いデザインという名のもとに、その無駄を誇らしげに披露することよりも、バスルームやキッチンを根こそぎ取り替えるようなことは、社会的な恥として謝罪すべきことなのだと感じなくていけません。

建築に対するアプローチ全般に関して言えば、私たちは、モダニズムの美的経験をどのように調整すれば、生態学的な害を減らせるのかを考えるのではなく、持続可能な生活とはどのようなものかを一から考えることから始めるべきなのです。

私たちが、この家を見るとき、それが実現可能で、ある種のリアリティを持つものだと、そういう見方をしてしまっているのだと思います。しかし、それがこのままある種のカテドラルとして存在してくれるのであれば、それは単発的な出来事に過ぎません。サヴォア邸が、単なる一過性の出来事なのであれば、サスティナビリティを目指す私たちの道程がそれによって破壊されるようなことはないと思うのですが。

しかし、サヴォア邸は単なる一つの建物なのではなく、昔も今もムーブメントの一部として存在しているのであって、その意味は、その壁の向こうへと飛び越えてしまっているのです。私もこの建物は賞賛しているのですが、私の言い方が強く批判的に聞こえてしまうのは、その建物がいまだに影響力を持ち続けているからです。それは、私たちのDNAに深く刻まれていて、建築や建設の世界の多く、いやほとんどは、現在でも心配になるほど表面的なものですし、私たちが変えていかなくては、と思うほどなのです。

純粋さ、あるいは純粋な空間という考え方には歴史的な背景があるのです。セントラルヒーティングなしでは、抽象的な空間デザインの議論など生まれてくることもありません。そうでなくては、ばかばかしくて考える気にもなりません。私が、モダニズム建築の歴史を研究し始めたころは、その憧れの建築に必要とされる膨大なエネルギー量のことを考えたことなどありませんでした。このような方向性で研究を始めて見ると、私たちがいかに、思い込みや刷り込まれた価値観を受け継ぎ、何も考えずに継続しているかがわかって心底驚かされました。

私たちが、知的な、あるいは文化的な進歩として受け入れていたことが、生態学のレンズを通して考えると、とてつもなく間違いであったり有害なことがあるのです。このことには、ますます注意を払わなくてはいけませんし、今日のデザインのあるべき姿をより完成形へと近づけるためにも模索していかなければいけません。

私たちは、安易に熱を使用する時代からは離れて、自然やエントロピーへの責任との関係を考慮し、近代主義的傾向からバランスを取り戻そうと努力をしているのだと思いますし、未来の姿に新しい楽観的なイメージを必要としているのだと思うのですが、それはどういうものになるとお考えですか?

答えはとてもシンプルです。再生可能な電力です。

ただ、予測可能な未来においては、化石燃料を代替するだけの電力は生み出すことはできません。それは例えると、一夜にして石油を電気とバッテリーに置き換えるようなことで難しい。ただ、それはもう近づいているのです。生態学的な大惨事が。今のところは、常に限界に達しているという感じです。もしかすると、その危機を脱するところまで技術が発展するかもしれません。でも、そうでない限りは、エネルギーを可能な限り戦略的かつ効率的に利用すべきです。

同様に、エネルギーを大量に消費する産業プロセスは、金融市場だけではなく、地球の周期と同期させていく必要があるのです。私たちは、鉄鋼を手放すことはできないだろうとは思いますが。鉄鋼に変わるものは他にないからです。ただ、その使用量を大幅に減らして、再生可能なものとして生産する必要が出てくるでしょう。それも、晴れた日や風の強い日に行うべきで、雨の日や夜に作業を行うべきではありません。プラントは高価なものであり、エネルギーは安価なものである。現状では、私たちはこういった考え方をしていて、その財政的な予想もすでにあるのです。だから、プラントを建設し、そのエネルギーの費用がいくらかかろうとも、それを払い続けることでプラントをずっと稼働させておくのです。それが化石燃料のやり方であり、地球上の生命の存在を脅かしているのです。

楽観的な考え方は必要だとは思いますが、現代の楽観的な建物は、1920年代や1930年代のそれとは全然異なるものでしょうね。

つまりサヴォア邸は、高エネルギー技術によって物事を解決する人類の無限の能力に対して楽観的なのであって、それは自然をコントロールする能力についての楽観性なのです。

現代の楽観的な建物は、小さく低エネルギーなもので、理想的には、新築ではなく改築であるべきです。それに可能な限りパッシブなものであってほしい。熱処理が弱くなり、耐久性に劣る素材を使用することになるので、計画的なメンテナンスが必要となるのかもしれませんし。

ある意味、それは後退の一歩に見えるかもしれません。ですが、それは自然のサイクルとの調和を目指し、物質的な豊さを手放すことも可能なことなのだ、と認識する世界への積極的な一歩なのです。ですから、楽観主義とは、一歩、また一歩と後退するその必要性を一種の喜びとして受け入れることなのだと思います。それは、生態系への謙虚さなのだと思います。

魅力的でエキサイティングなことでしょう。建築にとっては大きなチャンスなのだと思います。私たちには、ル・コルビュジエの想像したものよりも、もっと根本的な方法で、全てを再設計できるような、優秀で面白くも誠実な建築家が必要なのです。私たちは、低エネルギーな素材や、パッシブな快適性を保有する地域の洗練というものを再発見する必要があるのでしょう。それらは、モダニズムが意図的に取り除いたものなのです。私たちは、どういうわけだか、一周して戻ってきたのです。本質的で低エネルギーなヴァナキュラー建築から、化石燃料を無限に使用する高エネルギーのグローバルで画一的な感覚を経て、社会的、あるいは地理的な観点から場所の意味を再認識し、多様で生活を向上させる低エネルギーな建築へと意識を戻していく最中にいるのです。

2023年1月11日

Barnabas Calder: Modernism is an architecture born, fundamentally, of exuberant fossil fuel consumption. Most of the lessons it teaches us are therefore almost perfectly wrong for architecture during a climate crisis. Modernism’s attitudes to materials, servicing and transport are mostly aligned with ecological disaster.

I am deeply concerned with the way in which my profession, architectural education, continues to hold up modernism as having positive, direct lessons for students and practitioners to learn about the appearance, materiality and performance of architecture today.

IS VILLA SAVOYE TIMELESS?

I hope that if you ask that question again in 30 years’ time, maybe even ten years’ time, it will raise a massive laugh. I don’t think it’s timeless at all. It perhaps can feel like that because we are still in that moment; it’s not that there’s anything intrinsically timeless about it, it’s just that we haven’t moved on. We think it feels contemporary because we’re still copying it and because we’re still existing in a world that’s technologically and theoretically descended from that moment of enthusiastic splurging of fossil fuels. We’re still co-dependent with fossil-fuel energy. We’re still trying to substitute heat for labour in all parts of the building industry where possible.

IS VILLA SAVOYE EMBLEMATIC OF THE MODERN LIFESTYLE THAT WE STILL DESIRE?

I would say that Villa Savoye is a machine for burning fossil fuels, both onsite and remotely – particularly remotely, which was a new thing in the ‘20s. One of the excitements of early modernism was to remove the mess and maintenance of on-site wood or coal fires, which were dirty and required the unglamorous shifting of fuel. Modernists sought to replace these with oil fueled boilers, and electric heating and lighting that are cleaner and seemed almost magical in the way you just flicked switches to make things happen rather than have a servant shuffle in with a bucket of coal.

I would place the Villa Savoye as being, I suppose, late in the sequence of Le Corbusier’s explorations of what new energy technologies meant for life and the architecture that contained it. “A house is a machine for living” has been much discussed, but its meaning is clear: just as other machines convert fossil fuel energy into industrial production, a house, as a machine for living, converts fossil fuel energy into lifestyle.

It is from mass production that the “modern” lifestyle is born. The Villa Savoye depends on and celebrates two revolutions occurring in the years just before its construction: the internal combustion engine, and the remote distribution of centrally generated electricity. These two enable the Villa to be where it is, 20 kilometers outside Paris.

Private cars enabled the wealthy to sweep out of Paris at speed for the weekend. As you know, the ground plan of the building celebrates the turning circle of the car. In early drafts, Le Corbusier even proposed to drive cars up a ramp through the entire house and park higher in the building.

It’s also a building about electricity. Originally, he was very keen to try and electrically heat it, but the required level of energy would have necessitated the building of a special transformer station just for the house, which, even for the rich client, far exceeded the budget.

And of course the materials, too, are materials of the fossil fuel revolution – of high heat intensity. In his writing, Le Corbusier explicitly talks about the desire not to use natural materials. The “industrial materials” he advocates are materials processed using large amounts of intense fossil fuel heat. So the cement that bonds the concrete, and the steel that reinforces it, are both things that have essentially been known for thousands of years of human history. They’re only getting used in this quantity from the late nineteenth century because of the ever-more-abundant availability of cheap fossil fuel heat.

AND THE CONSEQUENCES OF THIS ARE DIRECTLY SEEN IN THE DESIGN.

Exactly! The enormous windows and absurd ratio of surface area to volume are celebrations of fossil fuel heat. If you look at any pre-industrial, pre fossil fuel window, the panes are very small and typically quite uneven. By this time, you can have huge sheets of glass the size of those that let you out from the salon into the central balcony and up to the sun terrace.

Those sheets of glass are vast, and they’re in moving doors. That is a level of glass technology only possible with the cheap heat that you’re getting in this period through coal and, increasingly, oil. So, the materials of the building are enormously heat-intense to produce, and those materials give rise to the five points of architecture; pilotis, free plan, free façade, horizontal windows, and Roof Garden.

The free plan is only possible thanks to the concrete and steel that mean that the vertical walls no longer do any work. The free facade is saying the same thing a slightly different way. The pilotis again are saying the same thing a slightly different way, but the result of all these freedoms is to produce a building where almost every wall, ceiling and floor is an outside surface. There is almost no point where heat leaking from one room ends up in another room of the house. And yet all that envelope is uninsulated (or very, very lightly insulated) single-thickness concrete, and steel. And therefore, the building is a continuous, enormous cold bridge.

This is essential, not incidental, to early modernist buildings. Cheap energy frees them from the way things have always been, in cold and hot climates alike. Many attitudes of design, during the last 100 years, have been about rebelling against the sensible and essential practices of previous generations, at the cost of huge fossil fuel inputs.

Historically, anywhere with a cold winter, you always clustered the rooms together around the sources of heat to preserve every joule you could, and to share this between rooms. Architects minimised the surface area to volume ratio. In early modernist villas this is reversed. Designers are utterly thrilled to be able to have enormous amounts of surface area and very, very minimal barriers between indoors and outdoors. They think of this breaking down of barriers conceptually and visually, but they are only able to do it in practice because of cheap heating. These great big, open-plan rooms, sometimes uniting more than one story of continuous space, would be uninhabitably drafty and unpleasant without powerful central heating.

WAS IT A SYMBOL OF POWER, OF DOMINATION?

Yes, I think there’s a very strong spirit in early modernism of a human triumph over nature. The Villa Savoye fits into that category.

But ultimately, it is also a clear case of hubris, much like our current situation: we are part of nature, not rulers over it. At the micro scale of the Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier’s desire to conquer nature ran ahead of the capabilities of the technologies that inspired him.The result was not a good machine for living.

Ultimately the level of heat inputs that the design required were beyond what even a rich family with an son whose health was suffering from the damp of the building could manage to keep up with.

AFTER READING YOUR BOOK, (ARCHITECTURE, FROM PREHISTORY TO CLIMATE EMERGENCY, PELICAN 2022) THERE WAS IMPRESSION THAT YOU LOOK FOR A DETERMINISM IN ENERGY PRODUCTION OR TECHNOLOGIES THAT ARE DEVELOPED IN THE HISTORY TO SUPPORT FORMS OF LIVING. OTHER THAN ENERGY, WE ARE INTERESTED TO ASK YOU IF YOU SEE, LET’S SAY, OTHER FACTORS THAT DISTINGUISH THIS HOUSE FROM OTHER HOUSES THAT COULD BE CONSIDERED WASTEFUL.

You said I seem to look for determinism. I didn’t start out looking for anything in that book other than answers to a simple question: “what does our current concern with energy use and architecture look like if you project it backwards?” This developed into: “what’s the relationship between energy use and architecture?” And the answer – that architecture and energy have always been inextricably bound together – came back utterly overwhelmingly, again and again and again. In contexts as diverse as the seasonality of Inuit housing, the energy basis for ancient monuments, the windows in Georgian houses, Le Corbusier’s villas, and on into the climate emergency.

The thing that makes the Villa Savoye such a good case study for this is that Le Corbusier was astonishingly good at rapidly reframing his architectural production in the light of technical changes that were still at a relatively early stage. This means there’s much less of the kind of messiness of having to explain traditionalist references to past architecture across several generations of energy change, as you would have to do for, for example, a building by Edwin Lutyens from the same period.

It would still be a building conceived around cars and central heating and easy transport of materials and concrete and bitumen and all sorts of other and very similar technologies, just as with Le Corbusier. But they are also in this very complex aesthetic discussion with hundreds or thousands of years of earlier architecture in a way that just makes the story have an awful lot of footnotes.

With Le Corbusier, because he’s so ruthlessly and sharply up-to-the-minute, the analysis is concise and clear.

FROM A MORE ARTISTIC POINT OF VIEW, WHEN YOU WERE THERE, AS AN ARCHITECT OR AS A PERSON THAT IS CONSCIOUS OF ARCHITECTURE, WHAT KIND OF OBJECTIVE QUALITIES, MATERIAL OR THEORETICAL DOES IT POSSESS? DOES ITS OVERALL EFFECT OVERCOME OUR ETHICAL DOUBTS?

For me, the huge positive that I get from the greatest of the modernists is that willingness to really rethink things deeply, and to take influences from surprising places. They had this capacity to grasp enough of the technical data to mean that they were designing with the right information, rather than copying other people’s motifs in the assumption that the technical demands are sufficiently alike for it to work.

In terms of the aesthetic and a kind of intellectual experience of visiting the Villa Savoye, I would like people to learn from it how to rethink architecture comprehensively around the conditions of their moment. As a project, that’s what it does so utterly outstandingly. And therefore, its profundity of rethinking is what we can take from it now, not its materials or motifs.

The challenge facing us is bigger and more exciting even than that faced by the early modernists: theirs was a shift within fossil fuelism, whereas we are needing to find a new architecture after fossil fuelism.

And that’s a much bigger shift to, for example, starting to adopt a building culture that is comfortable with fluctuating availability of electrical power as renewable generation rises and falls with the weather. Renewables are intermittent by nature. Redesigning our lives and our buildings as part of a renewable energy system is a challenge that needs a team of Le Corbusiers to resolve.

I found the Villa Savoye very beautiful and completely fascinating on my first visit, though I was disappointed to find it hedged-in and suburban after most of a century of car-driven urban growth, its commanding open views of countryside long gone. Now I find my pleasure in it muted by the knowledge of what it represents in making the latest fossil fuel luxuries of its moment so seductive and charismatic.

THERE IS A CERTAIN QUALITY IN ARRIVING ALMOST DIRECTLY TO YOUR PLACE, WASHING HANDS, AND CHOOSING BETWEEN TWO CIRCULATIONS SYSTEMS TO MOVE AROUND IN, TO SIT ON LARGE ROOF TERRACES. IT OFFERS A CERTAIN FREEDOM. CAN WE ALLOW OURSELVES SOME FREEDOMS IN PURSUIT OF JOY?

Double circulation is profligate, and we’ve got to stop being profligate. Single circulation is plenty in a single-family house. There’s absolutely no reason to have a second circulation route because it costs energy and carbon emissions to build, and to heat. It’s going to push down the density and therefore increase the demand for transport. The way the Villa Savoye was gloriously expansive, generating whole new types of space just because of the fun of sitting on the roof getting suntanned, or getting a different view of the landscape from another bit of open space within the building. When the building is also surrounded by open space, they’re glorious, but they are luxuries bought at the cost of additional carbon emissions.

They’re not the luxuries that we need to be thinking about in a climate emergency. We need to seek the luxury of a warm snug – the one part of the home where you’re really cosy in winter – which is an amazing sensory luxury.

In the UK, winter is typically cold and wet. This evening is no different and I’m sitting here in a house that only has natural gas central heating, which is carbon-intense and expensive, and so we have it off or very low all the time. I’m therefore wearing a thermal onesie and a scarf, and I can’t tell you how much I would love it if we had one little pool of warmth that I could approach and choose my distance from, the way that was always the case before central heating.

Thermal delight (Thermal delight in Architecture, Lisa Heschong, MIT 1979) is so far away from the thermal beige that the modernists painted over all of us. You ask about the experience of entering a building: I absolutely agree with thinking about the architectural promenade, but the architectural promenade in a truly sustainable single-family house is probably short because it’s probably small. One of the key characteristics of fossil fuels and housing has been to cheapen the construction of larger buildings. So, when you look at any non-elite housing from agrarian periods, it’s considerably smaller than the then a similar wealth percentile of the world population now.

So, if a low-carbon home is smaller, then there’s less of a promenade through it. But that doesn’t mean that can’t be tremendously subtle and interesting ways in which the designers have thought about the experience of moving from outdoors to indoors, above all thermally and in terms of light. Good passive thermal design can be an enormously rich architectural and aesthetic experience, collecting all the solar gain you can in cold weather, and keeping it out in warm weather.

Medium-rise, low-embodied carbon density, too, offers a thrilling challenge to architectural desginers: the ways in which density is achieved through elegance and thoughtfulness of planning, and the ways in which density also feeds into mutual warming between buildings, between dwelling units. This is territory for tremendous richness of architectural thought and aesthetic experience. But the aesthetic experience is less likely to be visually spectacular – instantly photogenic – in the way that the 20th and early 21st centuries have excessively privileged. It is more likely to be concerned with a thermal experience, which is a really difficult thing to convey in magazines and websites, and therefore will always be discriminated against by the architectural publication industry. But thermal pleasure is much more important to the experience of living in a house with low energy consumption and good temperature modulation. As increasing numbers of investigations show, the thermal is much more conducive than the visual to health, happiness and well-being.

It’s an enormous pleasure to be thermally comfortable. Each season it brings different types of pleasure. So next winter, when the first really cold day comes and you have the delightful experience of being cosy, or the next summer when it’s roasting outside and you come into a house that is blissfully cool - these pleaasures will never grow old, as even the best views lose some of their initial power with time and custom. Thermal delight is an absolutely core priority of architecture through the ages, and has always been much more of a concern than what buildings look like for everyone other than the richest 5% or so. Even for the very powerful, thermal pleasures were vital. Louis XIV’s bedroom is at the very centre of Versailles, and decorated absurdly grandly, but in size terms it is much smaller than the other key rooms of the palace – small enough, in fact, to be comfortable when heated by a fireplace.

WHAT DO YOU THINK CORBUSIER WOULD HAVE MADE OF REDUCE, REUSE, RECYCLE?

During his white villas period, Le Corbusier set himself against the age-old architectural pleasures of patina and palimpsest. Corb designed everything about the Villa Savoye to look brand new forever. Anything looking a bit worn in his work before about 1935 is a failure and needs to be replaced. Many architects are still preoccupied with the ideal of maintaining newness.

Other ways do exist - the Japanese landscape tradition celebrated the slow development of moss, or of water running down walls and leaving its marks. It celebrated things being replaced, but not indistinguishably, so that you arrive through time to a kind of grace derived from long use that I think we’re terrible at in much contemporary architecture. Buildings are photographed as perfect objects, as soon as possible after they’re finished.

The cult of the new and shiny is ecologically catastrophic. It should be socially embarrassing in a climate emergency to show people in your house or flat and have loads of new, pristine work done. We should feel the need to apologise for gutting and replacing bathrooms and kitchens as an embarrassing necessity, rather than proudly showing off the waste we have perpetrated in the name of good taste or good design.

In terms of our whole approach to architecture, we should not start out by thinking how we can tweak the aesthetic experiences of modernism to make them less ecologically harmful, but by considering from scratch what sustainable living will look like.

IF WE LOOK AT THIS HOUSE, WE SEE IT ALREADY AS A CERTAIN WAY OF DOING THAT WE CAN REPLICATE AND THAT WILL CREATE A CERTAIN REALITY. BUT, IF IT STAYS AS A CATHEDRAL, IT’S JUST A SINGULAR EVENT. IF VILLA SAVOYE IS JUST A SINGULAR EVENT IT DOESN’T RUIN OUR PATH TOWARDS SUSTAINABILITY.

But the Vila Savoye was not a single building, it was and still is part of a movement, and therefore its implications lie beyond its walls. The reason I sound so critical of a building that I admire in its own terms is because it is still influential. It’s so deep in our DNA, and many or most in the world of architecture and construction are, up to now, worryingly superficial in the way that they seem to feel we need to change things.

The idea of purity, of pure space is so historically situated. You know the whole idea of that discussion of abstract spatial design arises only when central heating comes in. Until then, it’s too stupid to even consider. When I started out in modernist architectural history I didn’t consider the enormous energy inputs required by the buildings I admired. Since I started taking my research in these directions, I’ve been really struck by the way we inherit assumptions and perceived values and carry them on without even thinking.

What we accept as intellectual and cultural progress can, when considered through an ecological lens, be incredibly wrong and damaging, and I think this is something we must be increasingly attentive to, to search for this more complete picture of what design needs to be today.

AS WE LEAVE THE TIME OF EASY HEAT AND STRIVE TO REBALANCE OUR MODERNISTIC TENDENCIES IN RELATION TO NATURE AND A RESPONSIBLE RATE OF ENTROPY, WE NEED NEW OPTIMISTIC IMAGES OF FUTURE EXISTENCE. WHAT DO YOU THINK THEY ARE?

The answer is very simple. It’s renewable electricity.

But we can’t, for the foreseeable future, generate enough of it to just substitute our fossil fuel use. For instance, we cannot just replace oil with electricity and batteries overnight. It would be, and is turning out to be, an ecological catastrophe. For now there is always a limit. Perhaps technologies might develop to the point where that’s no longer the case. But while that’s still the case, we should make use of energy as strategically and efficiently as possible.

Similarly, things like energy-intensive industrial processes need to be synchronized with earth’s cycles, not simply those of financial markets. I can’t see us getting fully away from steel because there’s nothing else that does what steel does anything like as well as steel. But we’ll need to use much less of it, and produce it with renewables, on sunny days and on windy days, and not when it’s raining, still, or at night. As it is, we have this mentality and this entire kind of financial set of assumptions: the plant is expensive, and energy is cheap. So you build your plant and then you just pay whatever the price is for the energy, and you keep the plant running the whole time. That is the fossil fuel way that is threatening the viability of life on earth.

I think there is a need for optimism, but I think the optimistic buildings of the present look very, very different from the optimistic buildings of the 1920s and 1930s.

So, the Villa Savoye is optimistic about the infinite capacity of humanity to fix things through high energy technologies. It is optimistic about the human capacity of controlling nature.

The optimistic building of now is small, low energy, ideally retrofitted rather than newly built. It is as passive as it can be. It’s perhaps going to require quite a lot more planned maintenance because it will use materials that aren’t as intensely heat processed and therefore are often less durable.

It may even look, in some ways, like a step backwards or a step down, but it’s a step towards a world in which we recognise that we can lose some material affluence in favor of achieving a reconciliation with natural cycles. I think optimism is, therefore, a kind of joyful embracing of the need to step downwards: a humbleness towards our ecosystem.

It’s fascinating and exciting, and I think it’s a huge opportunity for architecture. We need good, interesting, sincere architects to redesign everything more fundamentally than even Le Corbusier envisioned. We will have to rediscover the lost regional sophistication about local, low-energy materials and passive comfort, that was completely, deliberately undone by modernism. Somehow, we have journeyed in a full circle from essential low energy, vernacular buildings, through to high energy global uniformity of sensation, of unlimited fossil fuel use, and we are now on our way back to a socially and geographically conscious re-embraceof place, and of varied, life-enhancing, low—energy architectures.

11.01.2023

巴纳巴斯-考尔德:从根本上说,现代主义建筑诞生于对化石燃料的狂热消耗。因此,它教给我们的大部分经验在气候危机时期几乎是完全错误的。现代主义对材料、服务和运输的态度大多导向了生态灾难。

我深感忧虑的是,我所从事的专业——建筑学教育——继续将现代主义奉为正面的、直接的教条,供学生和从业人员学习当今建筑的外观、材料和性能。

萨伏伊别墅是永恒的吗?

我希望三十年后,甚至十年后,如果你再问这个问题,一定会引起哄堂大笑。我不认为它是永恒的。之所以会有这样的感觉,也许是因为我们还处在那个时刻;并不是说它本质上有什么永恒性,只是我们还没有向前看。我们之所以认为它具有当代感,是因为我们仍在复制它,也是因为我们仍存在于一个世界——在技术和理论上都源于那个热衷于挥霍化石燃料的时代。我们仍然依赖化石燃料能源。在建筑业的各个领域,我们仍在尽可能地用热能代替劳动力。

萨伏伊别墅是否象征着我们仍然向往的现代生活方式?

我想说,萨伏伊别墅是一台燃烧化石燃料的机器,既可以在现场燃烧,也可以远程燃烧,尤其是远程燃烧,这在 20 世纪 20 年代还是一件新鲜事。早期现代主义的兴奋点之一是消除现场木材或煤炭燃烧的混乱和维护工作——肮脏且需要枯燥地搬运燃料。现代主义者试图用燃油锅炉、电加热和电照明设备取而代之,这些设备更加清洁,而且似乎具有神奇的魔力,你只需轻按开关就能实现一切,而不是让仆人提着一桶煤进来。

在勒-柯布西耶探索新能源技术对生活和建筑的意义的过程中,我将萨伏伊别墅看作是他的晚期作品。”房子是生活的机器 “这句话已被广泛讨论,但它的含义是明确的:正如其他机器将化石燃料能源转化为工业产品一样,房子作为生活的机器,将化石燃料能源转化为生活方式。

“现代的”生活方式正是从大规模生产中诞生的。 萨伏伊别墅依靠并庆祝了在其建造前几年发生的两场革命:内燃机和远程集中供电。这两项革命使别墅得以立足于巴黎郊外 20 公里处。

私家车使富人能够在周末飞速离开巴黎。正如大家所知,别墅建筑的底层平面是依据汽车的转弯半径设计的。在早期的草案中,勒-柯布西耶甚至提议将汽车开上一条斜坡,穿过整栋房子,停在大楼的更高处。

这也是一座关于电的建筑。最初,勒-柯布西耶非常热衷于尝试用电加热,但所需的能源水平需要专门为这座房子建造一个变电站,即使是对于富裕的客户来说,这也远远超出了预算。

当然,这些材料也是化石燃料革命的材料--高热力强度。勒-柯布西耶在他的著作中明确提到不使用天然材料的愿望。他所倡导的 “工业材料 “是使用大量化石燃料高热量加工而成的材料。因此,粘合混凝土的水泥和加固混凝土的钢筋,在几千年的人类历史中都是众所周知的。只是从十九世纪末开始,由于廉价的化石燃料热量的日益丰富,它们才被大量使用。

其后果直接体现在设计上。

没错!巨大的窗户和荒谬的表面积与体积的比率都是对化石燃料热量的赞美。如果你看看任何工业化前、化石燃料使用前的窗户,窗格都非常小,而且通常很不平整。到了现在,你可以看到巨大的玻璃片,其大小可以让你的视线从沙龙出离到中央阳台后再上升阳光露台。

这些玻璃片非常大,而且装在移门里。在这个时期,只有通过煤炭和越来越多的石油才能获得廉价的热量,玻璃技术才能达到这样的水平。因此,建筑材料的生产需要大量热能,而这些材料造就了现代建筑的五要素:底层架空、自由平面、自由立面、横向长窗、屋顶花园。

自由平面的实现要归功于混凝土和钢材,这意味着垂直墙壁不再起任何作用。自由立面以略微不同的方式表达了同样的意思。底层架空再次以略微不同的方式表达了同样的意思。所有这些自由的结果是,几乎每一面墙壁、天花板和地板都是建筑物的外表面。从一个房间漏出的热量几乎不会进入另一个房间。

然而,所有的围护结构都是没有隔热层(或隔热层非常非常薄)的单层混凝土和钢材。因此,这座建筑就是一座连续的、巨大的冷桥。

这对于早期现代主义建筑来说是至关重要的,而不是附带的的。无论是在寒冷还是炎热的气候条件下,廉价的能源都使它们摆脱了一贯的方式。在过去的 100 年中,许多设计态度都是以巨大的化石燃料投入为代价,来反叛前几代人明智和基本的做法。

从历史上看,在冬季寒冷的地方,人们总是将房间集中在热源周围,以尽可能地保存每一焦热量,并在房间之间共享热量。建筑师将表面积与体积的比例降到最低。而在早期的现代主义别墅中,这种情况恰恰相反。设计师们对能够拥有巨大的表面积和极小的室内外障碍物感到无比兴奋。他们在概念上和视觉上都考虑到了这种障碍的打破,但在实践中,他们只能通过廉价的供暖来实现这一点。这些宽敞、开放式的房间,有时会将一层以上的连续空间连成一体,这些房间就会变得过于通风而无法居住、要不是有着强大的中央供暖系统,也将令人不适。

它是权力和统治的象征吗?

是的,我认为早期现代主义有一种非常强烈的人定胜天的精神。萨伏伊别墅就属于这一类。

但归根结底,它也是一个明显的傲慢的案例,就像我们现在的处境一样:我们是自然的一部分,而不是自然的统治者。在萨伏伊别墅的微观尺度上,勒-柯布西耶征服自然的欲望超越了激发他灵感的技术的能力。结果,这并不是一台适合居住的机器。

最终,设计所要求的热量输入水平甚至超出了一个富裕家庭的承受能力,这个家庭的一个儿子因建筑潮湿而健康受损。

读了您的书(《建筑,从史前到气候危机》,鹈鹕出版社 2022 年版)之后,我的印象是,您在寻找一种决定论,即生活的形式是由历史中能源生产相关技术的发展决定的。除了能源之外,我们也想问您,您是否发现,比方说,有其他因素将这座房子与其他被认为是浪费能源的房子区分开来。

你说我似乎在寻找决定论。除了回答一个简单的问题之外,我并没有在那本书中寻找任何东西: “如果倒推,关于能源使用与建筑造型,我们目前的关切是什么?” 后来发展成 “能源使用和建筑之间是什么关系?” 而答案--建筑与能源始终密不可分地联系在一起--一次又一次地以压倒性的优势出现。答案多种多样,包括因纽特人住房的季节性、古迹的能源基础、乔治亚风格房屋的窗户、勒-柯布西耶的别墅,一直到气候危机。

萨伏伊别墅之所以能成为一个很好的案例研究,是因为勒-柯布西耶异乎寻常地善于根据当时还处于相对早期阶段的技术变革,迅速重构他的建筑作品。这就意味着,没有那么多的混乱来自于不得不去解释那些传统主义者的借鉴——来自于过去的诞生于延续几代人的能源变革过程中的建筑,举例来说,就像同一时期埃德温-勒琴斯(Edwin Lutyens)那样。

这仍然是一座围绕汽车、集中供暖、材料便捷运输、混凝土和沥青以及其他各种非常相似的技术而设计的建筑,就像勒-柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)一样,。但是,他们也沉溺于与数百或数千年前的建筑进行着非常复杂的美学讨论,这仅仅使得故事的脚注多得可怕。

而对于勒-柯布西耶,由于他是如此无情和犀利地与时俱进,因此分析简洁明了。

从更具艺术性的角度来看,当你身临其境时,作为一名建筑师,或者作为一个有意识地关注建筑的人,它具有什么样的客观品质,是物质的还是理论的?它的整体效果是否能克服我们的道德疑虑?

对我来说,最伟大的现代主义者给我带来的巨大积极影响是,他们的意愿去真正地深入地重新思考问题,并从令人惊讶的地方汲取影响。他们有能力掌握足够多的技术数据,这意味着他们在设计时掌握了正确的信息,而不是照抄他人的样式且假设技术要求也是足够相像可以起效的。

就参观萨伏伊别墅的审美和知识体验而言,我希望人们能从中学到如何围绕当下的条件重新全面思考建筑。 作为一个项目,它在这方面做得非常出色。 因此,我们现在可以从它身上学到的是其反思的深刻性,而不是它的材料或样式。

我们面临的挑战甚至比早期现代主义者面临的挑战更大、更令人兴奋:他们的挑战是在化石燃料主义内部的转变,而我们则需要在化石燃料主义之后寻找新的建筑。

这是一个更大的转变,例如,开始采用一种建筑文化,以适应可再生能源发电量随天气起伏而波动的电力供应。可再生能源本质上是间歇性的。重新设计我们的生活和建筑,使之成为可再生能源系统的一部分,是一个需要柯布西耶团队来解决的挑战。

我第一次参观萨伏伊别墅时,就觉得它非常漂亮,而且非常迷人,不过,在经历了一个多世纪的汽车驱动的城市发展之后,我失望地发现它被包围住,被郊区化了,其开阔的乡村美景早已不复存在。现在,我发现我对它的喜爱被抑制,因为得知了它所代表的意义,使当时最新的化石燃料奢侈品变得如此诱惑和迷人。

有一种特质,几乎是直接到达你这里,洗手,在两个交通流线中选择一个在里面走动,然后坐在屋顶的大露台上,这样的感觉有一种特质。它提供了某种自由。在追求快乐的过程中,我们能否给自己一些自由?

双循环是一种挥霍,我们必须停止挥霍。在单户住宅中,单循环就足够了。绝对没有理由再建一个循环通道,因为建造和供暖都要耗费能源和碳排放。这会降低密度,从而增加对交通的需求。萨伏伊别墅的设计方式非常宽敞,产生了全新的空间类型,这只是因为坐在屋顶上晒太阳,或者从建筑中的另一小块开放空间获得一个不一样的观景点。当建筑周围也有空地时,它们固然光彩夺目,但却是以额外的碳排放为代价换来的奢侈品。

在气候危机下,我们需要思考的不是这些奢侈品。我们需要寻求的是一个温暖的小窝--冬天家中真正舒适的地方--这是一种令人惊叹的感官奢侈。

在英国,冬天通常又冷又潮湿。今天晚上也不例外,我坐在只有天然气中央暖气的房子里,天然气中央暖气既费碳又昂贵,所以我们一直都关着暖气或把温度调得很低。因此,我穿着保暖连身衣,围着围巾,如果我们有一个小小的温水池,我无法形容我是多么喜欢它,我可以接近它,选择我的距离,就像集中供暖之前的情况一样。

热愉悦(《建筑中的热愉悦》,丽莎-赫松,麻省理工学院,1979 年)与现代主义者在我们身上涂抹的热米色相去甚远。你问到了进入建筑的体验: 我完全同意对建筑学意义上的长廊的思考,但真正可持续发展的独户房屋的建筑长廊可能很短,因为它可能很小。化石燃料和住房的主要特点之一就是降低了大型建筑的建造成本。因此,当你查看农业时代的任何非精英住宅时,它都比现在世界人口中,类似的财富百分位人群的住宅要小得多。

因此,如果低碳住宅的面积较小,那么穿过住宅的长廊就会较少。 但这并不意味着设计师不能以精妙而有趣的方式考虑从室外到室内的体验,尤其是在热能和光线方面。好的被动式热能设计可以带来非常丰富的建筑和美学体验,在寒冷的天气里可以收集所有的太阳辐射,在温暖的天气里则可以将其阻挡在外。

中层低碳密度也给建筑设计师带来了令人激动的挑战:如何通过优雅周到的规划来实现密度,以及密度如何促进建筑物之间、居住单元之间的相互温暖。这是建筑思想和审美体验极为丰富的领域。但这种审美体验并没有在视觉上非常壮观,即刻上镜——这一特质在 20世纪和21世纪初被赋予过高的特权。它更倾向于热体验,而热体验在杂志和网站上是很难传达的,因此总是会受到建筑出版业的歧视。但是,对于居住在能耗低、温度调节性好的房屋中的体验来说,热愉悦感要重要得多。越来越多的研究表明,热能比视觉更有利于健康、快乐和幸福。

温暖舒适是一种巨大的享受。每个季节都会带来不同的乐趣。因此,下一个冬天,当第一个真正寒冷的日子来临时,你会有舒适惬意的愉悦体验;或者下一个夏天,当室外烈日炎炎时,你走进一间凉爽宜人的房子--这些愉悦永远不会过时,因为即使是最好的景观,也会随着时间和习惯而失去一些最初的力量。热愉悦绝对是古往今来建筑的核心要务,对于除了最富有的 5%左右的人之外的其他人来说,热愉悦始终比建筑外观更受关注。即使对权贵来说,热舒适也是至关重要的。路易十四的卧室位于凡尔赛宫的中心,装饰得非常华丽,但从面积上看,却比宫中其他主要房间小得多--事实上,小到用壁炉取暖也很舒适。

您认为柯布西耶会如何看待 “减量化、再利用、再循环”?

在勒-柯布西耶设计白色别墅期间,他将自己与古色古香的建筑乐趣相提并论。勒-柯布西耶设计的萨伏伊别墅的一切都焕然一新。大约在 1935 年之前,他的作品中任何看起来有点磨损的东西都是失败的,都需要更换。许多建筑师仍然执着于这种理想——保持崭新。

其他方式也确实存在--日本的景观传统赞美苔藓的缓慢生长,或水从墙上流下并留下痕迹。它赞美事物被替换,但并非毫无区别,这样你就能通过时间的推移感受到一种源于长期使用的优雅,而我认为我们在很多当代建筑中都很难做到这一点。建筑在完工后会尽快被拍成完美的物件。

对新的和闪亮的崇拜在生态上是灾难性的。在气候危机的情况下,让人们看到你的房子或公寓里有大量崭新的、焕然一新的工程,这在社会上应该是令人尴尬的。我们应该感到有必要为开膛破肚、更换浴室和厨房而道歉,因为这是令人尴尬的必要之举,而不是自豪地炫耀我们以好品味或好设计的名义造成的浪费。

就建筑学的整体发展路径而言,我们不应该就考虑如何调整现代主义的审美体验,使其减少对生态的危害作为出发点,而应该从头开始考虑可持续生活是什么样子的。

如果我们看这所房子,就会发现它已经是我们可以复制的某种方式,并将创造出某种现实。但是,如果它仍然是一座大教堂,那它就只是一个独特的事件。如果萨伏伊别墅只是一个单一的事件,它不会破坏我们的可持续发展之路。

但是,萨伏伊别墅并不是一座单独的建筑,它过去是,现在仍然是一场运动的一部分,因此它的影响超越了它的围墙。我之所以对一座我非常欣赏的建筑提出如此尖锐的批评,是因为它仍然具有影响力。它深深地扎根于我们的基因之中,而迄今为止,建筑界的许多人或大多数人似乎觉得我们只需要改良,这种肤浅的态度令人担忧。

纯粹性和纯粹空间的概念是如此具有历史意义。只有当集中供暖出现时,才会产生讨论抽象空间设计的整个想法。在此之前,考虑这个问题都太愚蠢了。 当我开始研究现代主义建筑史时,我并没有考虑到我所欣赏的建筑所需要的巨大能源投入。自从我开始朝着这些方向进行研究,我真的被我们继承假设和感知价值的方式所震惊,并且不假思索地将它们延续了下来。

我们所接受的知识和文化进步,如果从生态学的角度来看,可能会产生令人难以置信的错误和破坏,我认为这是我们必须日益关注的问题,以寻找当今设计所需要的更完整的图景。

当我们离开易热的时代,努力重新平衡我们的现代主义倾向与自然和负责任的熵率之间的关系时,我们需要新的未来存在的乐观图像。你认为它们是什么?

答案很简单。那就是可再生电力。

但在可预见的未来,我们无法产生足够的可再生能源来替代化石燃料的使用。例如,我们不可能在一夜之间用电力和电池取代石油。这将会是一场生态灾难,而且现在已经证明了这一点。就目前而言,总有一个限度。也许技术发展到一定程度就不再是这样了。 但在这种情况仍然存在的时候,我们应该尽可能有策略、有效地利用能源。

同样,能源密集型工业流程等也需要与地球周期同步,而不仅仅是金融市场的周期。我不认为我们能完全摆脱钢铁,因为没有任何其他东西能像钢铁那样做得那么好。 但我们需要大大减少钢铁的使用量,并利用可再生能源在晴天和大风天生产钢铁,而不是在下雨天、静止的时候或晚上生产钢铁。现在的情况是,我们有这样一种心态和一整套财务假设:发电厂很贵,而能源很便宜。因此,你只需建造发电厂,然后支付能源价格,让发电厂一直运转。这就是化石燃料的方式,它正威胁着地球生命的生存。

我认为乐观主义是有必要的,但我认为现在的乐观主义建筑与上世纪二三十年代的乐观主义建筑看起来非常非常不同。

因此,萨伏伊别墅乐观地认为,人类有无限的能力通过高耗能技术解决问题。它对人类控制自然的能力持乐观态度。

现在的乐观主义的建筑是小型的、低能耗的,最好是改造过的,而不是新建的。它尽可能是被动的。它可能需要更多有计划的维护,因为它使用的材料没有经过严格的热处理,因此通常不太耐用。

在某些方面,它甚至看起来像是一种倒退或退步,但这是迈向某个世界的一步,在这个世界里,我们认识到,我们可以失去一些物质上的富足,以实现与自然循环的和解。因此,我认为乐观主义是一种欣然接受向下迈步的需要:一种对我们生态系统的谦卑。

这是令人着迷的和兴奋的,我认为这对建筑学来说是一个巨大的机遇。我们需要优秀的、有趣的、真诚的建筑师,从更为根本的方面重新设计一切,甚至比勒-柯布西耶所设想的更为根本。 我们必须重新去发现丢失了的在地的复杂性、低能耗材料和被动舒适性,现代主义者有意地忽视了这些特质。不知不觉中,我们已经走过了一个完整的轮回,从基本的低能耗、乡土建筑,到高能耗的全球统一感观、化石燃料的无限使用,我们现在正走在回归社会和地域意识的道路上,重新拥抱地方,拥抱多样的、提高生活质量的低能耗建筑。

2023年1月11日

バルナバス・カルダー:モダニズムは、基本的に化石燃料を盛大に消費することで生まれた建築です。ですから、この気候危機の最中にある建築に対して、モダニズムが教えてくれることは、ほぼ完璧に間違っているということです。モダニズムにおける素材、サービス、それに輸送に対する態度は、大きく見て生態学的危機と並行しているものです。

私は、私の専門である建築教育が、モダニズムを標榜し続けていることに深い懸念を抱いています。それは、建築の外観や素材、機能を学ぼうとする学生や実務者に向けてのポジティブで直接的な教訓として理解されてしまっているわけですから。

サヴォア邸はタイムレスなものでしょうか?

30年後、いや10年後にはその質問が大笑いされるものになることを願っていますよ。タイムレスなものだとは全く思いませんね。私たちがまだその時代にいるからそう感じるのであって、本質的にタイムレスな何かがあるわけではなく、私たちがそこから進歩していないだけでしょう。現代的だと感じてしまうのは、私たちがその真似をしていて、化石燃料を狂ったようにばら撒いていたその時代から、技術的、あるいは理論的に派生した世界に私たちがいるからなのでしょう。私たちは未だに化石燃料と共依存の関係にありますし、建設業界のあらゆる分野では、可能な限り熱を労働力に変えようとしているのです。

サヴォア邸は、今もなお私たちの望む近代的なライフスタイルを象徴するものなのでしょうか?

サヴォア邸は、化石燃料を燃やすための機械なのだと言いたいです。それは現場でも遠隔地でも同じことです。特に遠隔地におけるそれは、1920年代には珍しいことでした。初期モダニズムの素晴らしさの一つは、薪や石炭などのメンテナンスやその面倒をなくしたことなのでしょう。薪を取り替えたりするのは、つまらなく、手の汚れる仕事でしたから。モダニストたちは、その仕事を石油を燃料とするボイラー、電気暖房、照明へと置き換えようとしていたのです。使用人が石炭の入ったバケツを持ってくるよりも清潔で、スイッチを押すだけの、ほとんど魔法のようなものですからね。

サヴォア邸は、新しく強力なエネルギー技術が生活や建築に何をもたらすのか、を探求したル・コルビュジエの一連の取り組みの中では、その後期に位置付けられるものだと思います。「住宅は住むための機械である」は多くの議論を生みましたが、その意味することは明確だと思います。つまり、機械が化石燃料のエネルギーを工業生産へと変換するように、住宅、いや住むためのそれは、化石燃料のエネルギーをライススタイルへと変換したのです。

「モダン」ライフスタイルは、大量生産から生まれたものですよね。サヴォア邸は、それが建設される直前の数年間に起こった二つの革命、つまり、内燃エンジンと集中型発電の遠隔地への配電技術に依存しながら、それらを褒めたたえているわけです。これら二つの技術があったからこそ、そのヴィラはパリから20キロも離れた場所にあるのでしょう。

自家用車のおかげで富裕層は、週末にでもさっとパリから抜け出る事が可能になったわけですし、ご存知のように、この建物の地上階平面図は車が旋回することを賞賛しているのです。初期の案では、家全体を貫くスロープを登って、車を上方に駐車することまで提案していました。

この建物は電気の建物でもあるのです。当初、彼はこの建物を電気で暖めようと熱心に取り組んでいたのですが、必要なエネルギーを得るのには、この家のためだけに特別な変圧装置が必要でしたし、それはこの裕福なクライアントにとっても予算内で収まるものではありませんでした。

もちろん、素材も化石燃料の革命によるものです。つまり、熱に強いものです。ル・コルビュジエはその著書の中で、自然素材は使いたくないと明確に述べています。彼の提唱する「工業材料」とは、化石燃料の高熱を大量に使用し、加工された材料のことです。コンクリートを繋げるためのセメントも、それを補強するための鋼鉄も、本来は何千年の人類の歴史において知られていたものではありますが。それがこれほど大量に使われるようになったのも、19世紀の後半の安価な化石燃料による熱が豊富に利用できるようになってからです。

その結果がデザインに直接的に表れている、と。

その通り!巨大な窓や、体積に不釣り合いなほどの表面積の割合は、化石燃料の熱の賜物ですよ。産業革命以前、つまり、化石燃料の使用される以前の窓を見てみると、ガラスはとても小さく、たいてい凸凹がついていますよね。それがこの時代になると、サロンからセントラルバルコニーへ、そしてサンテラスへと出るための巨大なガラスへと変わっていきます。

これらのガラス板はとてつもなく大きいものですが、それが可動式ドアに使われていたりするのです。石炭や石油によって安価な熱を得ることができたからこそ可能になったガラスの技術です。つまり、建築の素材はその生産に膨大な熱を必要とするわけですが、その素材が近代建築の5原則、ピロティ、自由な平面、自由な立面、水平連続窓、屋上庭園を作り上げたのでしょう。

自由な平面は、コンクリートと鉄のおかげで可能になるもので、垂直の壁は力学的には、もはや何の働きもしないということですよね。自由な立面は、同じことを少し違う言い方で言っているだけですね。ピロティもまた、同じことを少し違う言い方にしているだけなのですが、これらの自由さがもたらすのは、ほとんど全ての壁、天井、床が外壁面となる建物の生産なのです。

ある部屋から別の部屋へと熱が漏れていくといったことすらもなく、それなのに、外壁は全く断熱のされていない(されていたとしてもごく僅かに)単層のコンクリートや鉄骨なのです。ですから、建物は連続的で巨大なコールドブリッジとなるのです。

これは初期モダニズム建築にとっては、偶然ではなく必然のことです。安価なエネルギーは、その場所が寒かろうが暑かろうが、建築をこれまでのあり方から自由にしてくれるのです。この100年間における設計の多くは、化石燃料を莫大に投入するという代償を支払うことで、前の世代が実践してきた賢明で本質的な慣習に反旗を翻してきたのです。

歴史的を遡ると、寒冷地では、熱源を共有するためにも部屋をその周囲に集めることで、できる限りジュールを節約していましたし、建築家は体積に対する表面積の割合を最小限に抑えようとしていました。ところが、初期モダニズムのヴィラではそれが逆転しているのです。設計者たちは、膨大な表面積を抱えながらも屋内と屋外を隔てる障壁を極限まで小さくすることにすっかり興奮してしまったのです。彼らは、この障壁の破壊を概念的で視覚的なことのように捉えているようですが、実際、それは安価な暖房のおかげで可能になっていることなのです。このような大きく解放的な部屋は、複数階の連続した空間を一体化させたりするのですが、それも強力なセントラルヒーティングがなければ、隙間風が吹き込んで住み心地が悪いものになってしまいます。

それは権力、あるいは支配の象徴でもあったのでしょうか?

はい。初期モダニズムには、自然に対する人間の勝利という非常に強い精神があったのだと思います。サヴォア邸はまさにそのカテゴリーに入ります。

ただ結局は、傲慢だったということなのでしょう。私たちの今の状況もそうですが、私たちは自然の一部であって、それを支配するものではない。サヴォア邸をミクロなスケールで見てみると、ル・コルビュジエの自然を征服したいという要求が、そのインスピレーションのもととなったテクノロジーの能力を越えてしまったのだと思います。だからそれは、住むための機械とはならなかった。

この設計に必要とされた熱の入力レベルは、建物の湿気で健康を害した息子のいる裕福な家族でさえも維持できるレベルを超えてしまっていました。

あなたは、これからの生活を支えていくためにも、これまでの歴史の中で開発されてきた技術やエネルギーの生産体制におけるある決定論を模索しているのではないかと、あなたの本(ARCHITECTURE, FROM PREHISTORY TO CLIMATE EMERGENCY, PELICAN 2022) を読んで感じました。エネルギー以外の点で、この家を他の家と区別する要因、あるいは無駄だと考えられるものは何があるのか、お聞きしたいです。

私が決定論を探しているように見えるということですが、私はあの本の中でシンプルな問いに答える以外のことを求めていたわけではありません。その問いはつまり、「エネルギーの使用と建築への私たちの関心は、振り返って考えるとどのようなものであったのか?」と。それはさらに「エネルギーの使用と建築との関係とは?」という問いにつながるわけですが、その答えは、建築とエネルギーとは常に切っても切れない関係にある、というものでしたし、そのことは何度も戻ってくるものなのです。何度も何度も、本当に何度も。イヌイットの住居の季節性、古代遺跡のエネルギー基盤、ジョージアン様式の住宅の窓、そしてル・コルビュジエのヴィラ、そして気候変動という非常事態に至るまでのさまざまな文脈において、そうなのです。

ル・コルビュジエのサヴォア邸が、こうしたケーススタディに適しているのは、ル・コルビュジエがまだ初期段階であった技術的変化を察知して、自身の建築を素早く再構築することに驚くほど長けていたからです。それは、数世代にわたってエネルギーの変遷を経験した過去の建築への伝統主義的な言及を求められる面倒がなくなったことを意味します。それは例を出すと、エドウィン・ラッチェンスの建物なのですが。それも同時代のことですよ。

それもまた、ル・コルビュジエと同じように自動車やセントラルヒーティング、資材の容易な運搬、コンクリートやアスファルト、その他の類似技術を中心に考えられた建物であることには変わりないのですが。それらは何百年、何千年の歴史を持つ建築の複雑な美学的議論にも参与しているわけですし、その結果、すさまじいほどの注釈がつけられているのです。

ル・コルビュジエの場合は、非常に冷酷で、鋭く素早く、そして分析は簡潔で明瞭なわけですから。

もう少し芸術的な視点から、建築家として、あるいは建築に意識的な一人の人間として、その場に建ったときの印象を教えてください。その建築には、どのような客観的、物質的、理論的な質があるのだとお考えですか?倫理的な疑念に打ち勝つほどの全体性がもたらす効果がありましたか?

私にとって、偉大なモダニストたちから得られるとても良い点は、彼らの物事を深く捉え直そうとする意欲と、思いもよらないところから影響を受けとろうとする姿勢です。彼らは、技術的な条件が類似しているという理由から、他のモチーフをコピーするといったことはせずに、正しい情報を用いてデザインするという意味で、技術的なデータを十分に把握する能力を持っていました。

サヴォア邸を訪れた際の美的な、あるいは知的な体験に関してですね。皆さんにはその時々の状況に応じて総合的に再考する方法を学んで欲しいと考えています。プロジェクトとしてのそれは、素晴らしく傑出したものですよ。だからこそ、それを深く再考することが、今、私たちがこのプロジェクトから得られることなのです。単に素材やモチーフ、といったことではなく。

私たちの直面している課題は、初期モダニストたちのそれよりもさらに大きくエキサイティングなものです。彼らは、化石燃料主義の中で転換を強いられただけですが、私たちには、それに変わる新しい建築を見つける必要があるのです。

それはより大きな転換となるでしょう。例えばですが、天候によって増減する再生可能エネルギーによる電力供給の不安定さを内包する建築文化を受け入れ始めることなのかもしれません。再生可能エネルギーは本来、断続的なものですから。私たちの生活と建物を再生可能エネルギーのシステムの一部として再設計することは、ル・コルビュジエのチームの助けとともに解決すべき課題です。

初めてサヴォア邸を訪れたとき、とても美しく魅力的なものだと感じました。ただ、一世紀近くにわたって車を中心とする都市が発展したおかげで、田園地帯の雄大で開放的な景色はとうの昔に消え去り、今は生垣に囲まれた郊外になってしまっていることには、がっかりしました。当時の最先端の化石燃料を使った贅沢品が、これほどまで魅力的でカリスマ的なものになっているその理由を知っている今では、私は自身の喜びが薄れていくことに気づいてしまいました。

家に着くとすぐに手が洗えて、サーキュレーションシステムも二つあって、そのどちらかを選んで登っていき、広いテラスに横たわれる。そういった、ある種の自由がこの建築にはあるのだと思いますが、私たちにこうした喜びを追及するための自由は許されるのでしょうか?

サーキュレーションシステムが二つあることは浪費ですから、浪費はやめないといけませんね。戸建て住宅なら一つで十分でしょう。建設するのにエネルギーも二酸化炭素排出量も増えて、暖房費もかかるわけですから、全く必要ないものです。そうすれば二酸化炭素排出量も減りますし、その分を輸送に使えます。

サヴォア邸は、とてつもなく広大なもので、屋上に座って日光浴をしたり、内部のオープンスペースから別の景色を眺めるといった、楽しみのためだけに作られた全く新しいタイプの空間を作り出しています。建物自体もオープンスペースに囲まれているのであれば、さらに素晴らしいものになるとは思いますが、それはまた、炭素排出量を増やして買うような贅沢品なのです。

それは、気候変動という緊急時に考えるようなラグジュアリーではなく、私たちが求めるべきは、暖かな隠れ家のようなラグジュアリーなのです。

イギリスの冬は、寒く湿気も多いです。私は、今夜も変わらず、炭素排出量が多く、高価な天然ガスのセントラルヒーティングしかないこの家に座っているのですが、その設定温度はとても低く設定したり、あるいはオフにしているのです。ですから、私は、保温性のあるワンジーを着て、スカーフを巻いているのですが。セントラルヒーティングが導入される以前のように、小さくて暖かなプールがあって、そこに近づいたりして距離を選べることができたら、どんなにいいだろうと考えるわけです。

『Thermal delight』(Thermal delight in Architecture, Lisa Heschong, MIT 1979)は、モダニストたちが私たちの上に塗りつぶしたベージュ色の(均一な)熱とは全く異なる考え方です。建物に入るときの経験について聞いているのでしたね。もちろん建築的プロムナードの考えには私も大賛成です。ただ、真にサスティナブルな戸建て住宅の建築的プロムナードは多分もっと短いものですよね。もっと小さいものになるでしょうから。化石燃料と住宅との関係において重要な特徴の一つは、大きな建物を安く建てることでした。ですから、農業時代の非エリート階級の住宅を見てみると、現在の世界人口における同程度の富の人々の住宅よりもかなり小さいのです。

低炭素住宅が小さいものであれば、その中を散歩(プロムナード)することも少なくなります。だからといって、設計者が建物の外から中へと移動する体験に対して繊細な感性を持たず、興味がないということでもないのですが。それは熱的な面でも光的な面でもそうです。優れたパッシブ・サーマル・デザインは、とても豊かな建築的、美的体験となり得るものです。寒冷地ではできる限りの日射熱を集め、温暖なところでは日射熱を遮断するのです。

中層の低炭素建築も建築デザイナーにとってはスリリングな挑戦になるでしょう。低炭素であることが、エレガントで思慮深いプランニングや、建物間あるいは住戸間を相合に暖房する方法を見つけるきっかけとなるでしょうし、建築的思想や美的経験を非常に豊かにしてくれる領域なのだと思います。しかし、その美的経験は、視覚的に華やかなものではなく、20世紀や21世紀初頭に過度な優遇を受けてきたような即座に写真映えするものではないでしょう。それは温熱的な経験によるものですし、雑誌やウェブサイトでは伝えるのが本当に難しいものだと思います。ですから、建築の出版業界からは、常に差別されるようなものになるのかもしれませんが。ですが、エネルギー消費量が少なく温度調整に優れた住宅に住むという体験の中では、温熱的な喜びの方がはるかに重要なことです。多くの研究が示すように、健康や幸福、ウェルビーイングにとっては、視覚的なものよりも温熱的なものの方がはるかに重要なのです。

温熱的に快適であることは、大きな喜びです。季節ごとに異なる喜びを味わえるのです。冬には、本当に寒い日がやって来ると、家の居心地の良さを実感しますし、夏には、外が焼けつくような暑さでも、家の中が涼しいと、この上なく幸せを感じます。こうした喜びは決して古びることありません。最高の景色は、時の経過と慣習によって、その魅力が失われていくものですが。温熱的な喜びは、時代を超えて建築の絶対的な核をなす優先事項です。人口の5%程度の富裕層以外の人々にとっては、建物がどう見えるかよりもずっと重要な関心事であったのです。それに、たとえ非常に強力な権力を持っている人でも、温熱環境は不可欠なものでした。ルイ14世の寝室は、ヴェルサイユ宮殿の中心にあって、そこにはとんでもなく壮大な装飾が施されているのですが、その部屋のサイズは、宮殿内のどの部屋よりも小さいのです。暖炉で暖めて過ごすには、十分な小ささです。

ル・コルビュジエは、リデュース、リユース、リサイクルの考えについて、どう捉えていたと思いますか?

ル・コルビュジエは、白のヴィラの時代において、パティーナとパリンプセトという古くからの建築の楽しみに対抗したわけですよね。サヴォア邸においては全てが真新しく見えるように設計しました。1935年ごろより前に作られた彼の作品は、少しでも古びて見えるものは失敗作として、取り替える必要があったのです。多くの建築家は、いまだに新しさを保つという理想にとらわれています。

そうではない方法もあって、日本の伝統的な景観は、苔がゆっくりと成長することや、水が壁を流れ落ち、その跡が残ってしまうことを賞賛しています。それは移り変わるものへの賛美であって、変わらないものへのそれではなく、長い時間のあとで表れる、ある種の優美さのことなのです。それは、多くの現代建築が苦手としていることです。建物は、完成後にはできるだけ早く、完璧なオブジェとして撮影されるのですから。

新しいものやピカピカなものへの崇拝は、生物学的には破滅的なものなのです。気候変動という非常事態の中で、新品でまっさらなもので満たされた家や部屋を見せつけることなど、社会的に恥ずべきことなのです。良い趣味や良いデザインという名のもとに、その無駄を誇らしげに披露することよりも、バスルームやキッチンを根こそぎ取り替えるようなことは、社会的な恥として謝罪すべきことなのだと感じなくていけません。

建築に対するアプローチ全般に関して言えば、私たちは、モダニズムの美的経験をどのように調整すれば、生態学的な害を減らせるのかを考えるのではなく、持続可能な生活とはどのようなものかを一から考えることから始めるべきなのです。

私たちが、この家を見るとき、それが実現可能で、ある種のリアリティを持つものだと、そういう見方をしてしまっているのだと思います。しかし、それがこのままある種のカテドラルとして存在してくれるのであれば、それは単発的な出来事に過ぎません。サヴォア邸が、単なる一過性の出来事なのであれば、サスティナビリティを目指す私たちの道程がそれによって破壊されるようなことはないと思うのですが。

しかし、サヴォア邸は単なる一つの建物なのではなく、昔も今もムーブメントの一部として存在しているのであって、その意味は、その壁の向こうへと飛び越えてしまっているのです。私もこの建物は賞賛しているのですが、私の言い方が強く批判的に聞こえてしまうのは、その建物がいまだに影響力を持ち続けているからです。それは、私たちのDNAに深く刻まれていて、建築や建設の世界の多く、いやほとんどは、現在でも心配になるほど表面的なものですし、私たちが変えていかなくては、と思うほどなのです。

純粋さ、あるいは純粋な空間という考え方には歴史的な背景があるのです。セントラルヒーティングなしでは、抽象的な空間デザインの議論など生まれてくることもありません。そうでなくては、ばかばかしくて考える気にもなりません。私が、モダニズム建築の歴史を研究し始めたころは、その憧れの建築に必要とされる膨大なエネルギー量のことを考えたことなどありませんでした。このような方向性で研究を始めて見ると、私たちがいかに、思い込みや刷り込まれた価値観を受け継ぎ、何も考えずに継続しているかがわかって心底驚かされました。

私たちが、知的な、あるいは文化的な進歩として受け入れていたことが、生態学のレンズを通して考えると、とてつもなく間違いであったり有害なことがあるのです。このことには、ますます注意を払わなくてはいけませんし、今日のデザインのあるべき姿をより完成形へと近づけるためにも模索していかなければいけません。

私たちは、安易に熱を使用する時代からは離れて、自然やエントロピーへの責任との関係を考慮し、近代主義的傾向からバランスを取り戻そうと努力をしているのだと思いますし、未来の姿に新しい楽観的なイメージを必要としているのだと思うのですが、それはどういうものになるとお考えですか?

答えはとてもシンプルです。再生可能な電力です。

ただ、予測可能な未来においては、化石燃料を代替するだけの電力は生み出すことはできません。それは例えると、一夜にして石油を電気とバッテリーに置き換えるようなことで難しい。ただ、それはもう近づいているのです。生態学的な大惨事が。今のところは、常に限界に達しているという感じです。もしかすると、その危機を脱するところまで技術が発展するかもしれません。でも、そうでない限りは、エネルギーを可能な限り戦略的かつ効率的に利用すべきです。

同様に、エネルギーを大量に消費する産業プロセスは、金融市場だけではなく、地球の周期と同期させていく必要があるのです。私たちは、鉄鋼を手放すことはできないだろうとは思いますが。鉄鋼に変わるものは他にないからです。ただ、その使用量を大幅に減らして、再生可能なものとして生産する必要が出てくるでしょう。それも、晴れた日や風の強い日に行うべきで、雨の日や夜に作業を行うべきではありません。プラントは高価なものであり、エネルギーは安価なものである。現状では、私たちはこういった考え方をしていて、その財政的な予想もすでにあるのです。だから、プラントを建設し、そのエネルギーの費用がいくらかかろうとも、それを払い続けることでプラントをずっと稼働させておくのです。それが化石燃料のやり方であり、地球上の生命の存在を脅かしているのです。

楽観的な考え方は必要だとは思いますが、現代の楽観的な建物は、1920年代や1930年代のそれとは全然異なるものでしょうね。

つまりサヴォア邸は、高エネルギー技術によって物事を解決する人類の無限の能力に対して楽観的なのであって、それは自然をコントロールする能力についての楽観性なのです。

現代の楽観的な建物は、小さく低エネルギーなもので、理想的には、新築ではなく改築であるべきです。それに可能な限りパッシブなものであってほしい。熱処理が弱くなり、耐久性に劣る素材を使用することになるので、計画的なメンテナンスが必要となるのかもしれませんし。

ある意味、それは後退の一歩に見えるかもしれません。ですが、それは自然のサイクルとの調和を目指し、物質的な豊さを手放すことも可能なことなのだ、と認識する世界への積極的な一歩なのです。ですから、楽観主義とは、一歩、また一歩と後退するその必要性を一種の喜びとして受け入れることなのだと思います。それは、生態系への謙虚さなのだと思います。

魅力的でエキサイティングなことでしょう。建築にとっては大きなチャンスなのだと思います。私たちには、ル・コルビュジエの想像したものよりも、もっと根本的な方法で、全てを再設計できるような、優秀で面白くも誠実な建築家が必要なのです。私たちは、低エネルギーな素材や、パッシブな快適性を保有する地域の洗練というものを再発見する必要があるのでしょう。それらは、モダニズムが意図的に取り除いたものなのです。私たちは、どういうわけだか、一周して戻ってきたのです。本質的で低エネルギーなヴァナキュラー建築から、化石燃料を無限に使用する高エネルギーのグローバルで画一的な感覚を経て、社会的、あるいは地理的な観点から場所の意味を再認識し、多様で生活を向上させる低エネルギーな建築へと意識を戻していく最中にいるのです。

2023年1月11日

Barnabas Calder: Modernism is an architecture born, fundamentally, of exuberant fossil fuel consumption. Most of the lessons it teaches us are therefore almost perfectly wrong for architecture during a climate crisis. Modernism’s attitudes to materials, servicing and transport are mostly aligned with ecological disaster.

I am deeply concerned with the way in which my profession, architectural education, continues to hold up modernism as having positive, direct lessons for students and practitioners to learn about the appearance, materiality and performance of architecture today.

IS VILLA SAVOYE TIMELESS?

I hope that if you ask that question again in 30 years’ time, maybe even ten years’ time, it will raise a massive laugh. I don’t think it’s timeless at all. It perhaps can feel like that because we are still in that moment; it’s not that there’s anything intrinsically timeless about it, it’s just that we haven’t moved on. We think it feels contemporary because we’re still copying it and because we’re still existing in a world that’s technologically and theoretically descended from that moment of enthusiastic splurging of fossil fuels. We’re still co-dependent with fossil-fuel energy. We’re still trying to substitute heat for labour in all parts of the building industry where possible.

IS VILLA SAVOYE EMBLEMATIC OF THE MODERN LIFESTYLE THAT WE STILL DESIRE?

I would say that Villa Savoye is a machine for burning fossil fuels, both onsite and remotely – particularly remotely, which was a new thing in the ‘20s. One of the excitements of early modernism was to remove the mess and maintenance of on-site wood or coal fires, which were dirty and required the unglamorous shifting of fuel. Modernists sought to replace these with oil fueled boilers, and electric heating and lighting that are cleaner and seemed almost magical in the way you just flicked switches to make things happen rather than have a servant shuffle in with a bucket of coal.

I would place the Villa Savoye as being, I suppose, late in the sequence of Le Corbusier’s explorations of what new energy technologies meant for life and the architecture that contained it. “A house is a machine for living” has been much discussed, but its meaning is clear: just as other machines convert fossil fuel energy into industrial production, a house, as a machine for living, converts fossil fuel energy into lifestyle.

It is from mass production that the “modern” lifestyle is born. The Villa Savoye depends on and celebrates two revolutions occurring in the years just before its construction: the internal combustion engine, and the remote distribution of centrally generated electricity. These two enable the Villa to be where it is, 20 kilometers outside Paris.

Private cars enabled the wealthy to sweep out of Paris at speed for the weekend. As you know, the ground plan of the building celebrates the turning circle of the car. In early drafts, Le Corbusier even proposed to drive cars up a ramp through the entire house and park higher in the building.

It’s also a building about electricity. Originally, he was very keen to try and electrically heat it, but the required level of energy would have necessitated the building of a special transformer station just for the house, which, even for the rich client, far exceeded the budget.

And of course the materials, too, are materials of the fossil fuel revolution – of high heat intensity. In his writing, Le Corbusier explicitly talks about the desire not to use natural materials. The “industrial materials” he advocates are materials processed using large amounts of intense fossil fuel heat. So the cement that bonds the concrete, and the steel that reinforces it, are both things that have essentially been known for thousands of years of human history. They’re only getting used in this quantity from the late nineteenth century because of the ever-more-abundant availability of cheap fossil fuel heat.

AND THE CONSEQUENCES OF THIS ARE DIRECTLY SEEN IN THE DESIGN.

Exactly! The enormous windows and absurd ratio of surface area to volume are celebrations of fossil fuel heat. If you look at any pre-industrial, pre fossil fuel window, the panes are very small and typically quite uneven. By this time, you can have huge sheets of glass the size of those that let you out from the salon into the central balcony and up to the sun terrace.

Those sheets of glass are vast, and they’re in moving doors. That is a level of glass technology only possible with the cheap heat that you’re getting in this period through coal and, increasingly, oil. So, the materials of the building are enormously heat-intense to produce, and those materials give rise to the five points of architecture; pilotis, free plan, free façade, horizontal windows, and Roof Garden.

The free plan is only possible thanks to the concrete and steel that mean that the vertical walls no longer do any work. The free facade is saying the same thing a slightly different way. The pilotis again are saying the same thing a slightly different way, but the result of all these freedoms is to produce a building where almost every wall, ceiling and floor is an outside surface. There is almost no point where heat leaking from one room ends up in another room of the house. And yet all that envelope is uninsulated (or very, very lightly insulated) single-thickness concrete, and steel. And therefore, the building is a continuous, enormous cold bridge.

This is essential, not incidental, to early modernist buildings. Cheap energy frees them from the way things have always been, in cold and hot climates alike. Many attitudes of design, during the last 100 years, have been about rebelling against the sensible and essential practices of previous generations, at the cost of huge fossil fuel inputs.

Historically, anywhere with a cold winter, you always clustered the rooms together around the sources of heat to preserve every joule you could, and to share this between rooms. Architects minimised the surface area to volume ratio. In early modernist villas this is reversed. Designers are utterly thrilled to be able to have enormous amounts of surface area and very, very minimal barriers between indoors and outdoors. They think of this breaking down of barriers conceptually and visually, but they are only able to do it in practice because of cheap heating. These great big, open-plan rooms, sometimes uniting more than one story of continuous space, would be uninhabitably drafty and unpleasant without powerful central heating.

WAS IT A SYMBOL OF POWER, OF DOMINATION?

Yes, I think there’s a very strong spirit in early modernism of a human triumph over nature. The Villa Savoye fits into that category.

But ultimately, it is also a clear case of hubris, much like our current situation: we are part of nature, not rulers over it. At the micro scale of the Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier’s desire to conquer nature ran ahead of the capabilities of the technologies that inspired him.The result was not a good machine for living.

Ultimately the level of heat inputs that the design required were beyond what even a rich family with an son whose health was suffering from the damp of the building could manage to keep up with.

AFTER READING YOUR BOOK, (ARCHITECTURE, FROM PREHISTORY TO CLIMATE EMERGENCY, PELICAN 2022) THERE WAS IMPRESSION THAT YOU LOOK FOR A DETERMINISM IN ENERGY PRODUCTION OR TECHNOLOGIES THAT ARE DEVELOPED IN THE HISTORY TO SUPPORT FORMS OF LIVING. OTHER THAN ENERGY, WE ARE INTERESTED TO ASK YOU IF YOU SEE, LET’S SAY, OTHER FACTORS THAT DISTINGUISH THIS HOUSE FROM OTHER HOUSES THAT COULD BE CONSIDERED WASTEFUL.

You said I seem to look for determinism. I didn’t start out looking for anything in that book other than answers to a simple question: “what does our current concern with energy use and architecture look like if you project it backwards?” This developed into: “what’s the relationship between energy use and architecture?” And the answer – that architecture and energy have always been inextricably bound together – came back utterly overwhelmingly, again and again and again. In contexts as diverse as the seasonality of Inuit housing, the energy basis for ancient monuments, the windows in Georgian houses, Le Corbusier’s villas, and on into the climate emergency.

The thing that makes the Villa Savoye such a good case study for this is that Le Corbusier was astonishingly good at rapidly reframing his architectural production in the light of technical changes that were still at a relatively early stage. This means there’s much less of the kind of messiness of having to explain traditionalist references to past architecture across several generations of energy change, as you would have to do for, for example, a building by Edwin Lutyens from the same period.

It would still be a building conceived around cars and central heating and easy transport of materials and concrete and bitumen and all sorts of other and very similar technologies, just as with Le Corbusier. But they are also in this very complex aesthetic discussion with hundreds or thousands of years of earlier architecture in a way that just makes the story have an awful lot of footnotes.

With Le Corbusier, because he’s so ruthlessly and sharply up-to-the-minute, the analysis is concise and clear.

FROM A MORE ARTISTIC POINT OF VIEW, WHEN YOU WERE THERE, AS AN ARCHITECT OR AS A PERSON THAT IS CONSCIOUS OF ARCHITECTURE, WHAT KIND OF OBJECTIVE QUALITIES, MATERIAL OR THEORETICAL DOES IT POSSESS? DOES ITS OVERALL EFFECT OVERCOME OUR ETHICAL DOUBTS?

For me, the huge positive that I get from the greatest of the modernists is that willingness to really rethink things deeply, and to take influences from surprising places. They had this capacity to grasp enough of the technical data to mean that they were designing with the right information, rather than copying other people’s motifs in the assumption that the technical demands are sufficiently alike for it to work.

In terms of the aesthetic and a kind of intellectual experience of visiting the Villa Savoye, I would like people to learn from it how to rethink architecture comprehensively around the conditions of their moment. As a project, that’s what it does so utterly outstandingly. And therefore, its profundity of rethinking is what we can take from it now, not its materials or motifs.

The challenge facing us is bigger and more exciting even than that faced by the early modernists: theirs was a shift within fossil fuelism, whereas we are needing to find a new architecture after fossil fuelism.

And that’s a much bigger shift to, for example, starting to adopt a building culture that is comfortable with fluctuating availability of electrical power as renewable generation rises and falls with the weather. Renewables are intermittent by nature. Redesigning our lives and our buildings as part of a renewable energy system is a challenge that needs a team of Le Corbusiers to resolve.

I found the Villa Savoye very beautiful and completely fascinating on my first visit, though I was disappointed to find it hedged-in and suburban after most of a century of car-driven urban growth, its commanding open views of countryside long gone. Now I find my pleasure in it muted by the knowledge of what it represents in making the latest fossil fuel luxuries of its moment so seductive and charismatic.

THERE IS A CERTAIN QUALITY IN ARRIVING ALMOST DIRECTLY TO YOUR PLACE, WASHING HANDS, AND CHOOSING BETWEEN TWO CIRCULATIONS SYSTEMS TO MOVE AROUND IN, TO SIT ON LARGE ROOF TERRACES. IT OFFERS A CERTAIN FREEDOM. CAN WE ALLOW OURSELVES SOME FREEDOMS IN PURSUIT OF JOY?

Double circulation is profligate, and we’ve got to stop being profligate. Single circulation is plenty in a single-family house. There’s absolutely no reason to have a second circulation route because it costs energy and carbon emissions to build, and to heat. It’s going to push down the density and therefore increase the demand for transport. The way the Villa Savoye was gloriously expansive, generating whole new types of space just because of the fun of sitting on the roof getting suntanned, or getting a different view of the landscape from another bit of open space within the building. When the building is also surrounded by open space, they’re glorious, but they are luxuries bought at the cost of additional carbon emissions.

They’re not the luxuries that we need to be thinking about in a climate emergency. We need to seek the luxury of a warm snug – the one part of the home where you’re really cosy in winter – which is an amazing sensory luxury.

In the UK, winter is typically cold and wet. This evening is no different and I’m sitting here in a house that only has natural gas central heating, which is carbon-intense and expensive, and so we have it off or very low all the time. I’m therefore wearing a thermal onesie and a scarf, and I can’t tell you how much I would love it if we had one little pool of warmth that I could approach and choose my distance from, the way that was always the case before central heating.

Thermal delight (Thermal delight in Architecture, Lisa Heschong, MIT 1979) is so far away from the thermal beige that the modernists painted over all of us. You ask about the experience of entering a building: I absolutely agree with thinking about the architectural promenade, but the architectural promenade in a truly sustainable single-family house is probably short because it’s probably small. One of the key characteristics of fossil fuels and housing has been to cheapen the construction of larger buildings. So, when you look at any non-elite housing from agrarian periods, it’s considerably smaller than the then a similar wealth percentile of the world population now.

So, if a low-carbon home is smaller, then there’s less of a promenade through it. But that doesn’t mean that can’t be tremendously subtle and interesting ways in which the designers have thought about the experience of moving from outdoors to indoors, above all thermally and in terms of light. Good passive thermal design can be an enormously rich architectural and aesthetic experience, collecting all the solar gain you can in cold weather, and keeping it out in warm weather.

Medium-rise, low-embodied carbon density, too, offers a thrilling challenge to architectural desginers: the ways in which density is achieved through elegance and thoughtfulness of planning, and the ways in which density also feeds into mutual warming between buildings, between dwelling units. This is territory for tremendous richness of architectural thought and aesthetic experience. But the aesthetic experience is less likely to be visually spectacular – instantly photogenic – in the way that the 20th and early 21st centuries have excessively privileged. It is more likely to be concerned with a thermal experience, which is a really difficult thing to convey in magazines and websites, and therefore will always be discriminated against by the architectural publication industry. But thermal pleasure is much more important to the experience of living in a house with low energy consumption and good temperature modulation. As increasing numbers of investigations show, the thermal is much more conducive than the visual to health, happiness and well-being.

It’s an enormous pleasure to be thermally comfortable. Each season it brings different types of pleasure. So next winter, when the first really cold day comes and you have the delightful experience of being cosy, or the next summer when it’s roasting outside and you come into a house that is blissfully cool - these pleaasures will never grow old, as even the best views lose some of their initial power with time and custom. Thermal delight is an absolutely core priority of architecture through the ages, and has always been much more of a concern than what buildings look like for everyone other than the richest 5% or so. Even for the very powerful, thermal pleasures were vital. Louis XIV’s bedroom is at the very centre of Versailles, and decorated absurdly grandly, but in size terms it is much smaller than the other key rooms of the palace – small enough, in fact, to be comfortable when heated by a fireplace.

WHAT DO YOU THINK CORBUSIER WOULD HAVE MADE OF REDUCE, REUSE, RECYCLE?

During his white villas period, Le Corbusier set himself against the age-old architectural pleasures of patina and palimpsest. Corb designed everything about the Villa Savoye to look brand new forever. Anything looking a bit worn in his work before about 1935 is a failure and needs to be replaced. Many architects are still preoccupied with the ideal of maintaining newness.

Other ways do exist - the Japanese landscape tradition celebrated the slow development of moss, or of water running down walls and leaving its marks. It celebrated things being replaced, but not indistinguishably, so that you arrive through time to a kind of grace derived from long use that I think we’re terrible at in much contemporary architecture. Buildings are photographed as perfect objects, as soon as possible after they’re finished.

The cult of the new and shiny is ecologically catastrophic. It should be socially embarrassing in a climate emergency to show people in your house or flat and have loads of new, pristine work done. We should feel the need to apologise for gutting and replacing bathrooms and kitchens as an embarrassing necessity, rather than proudly showing off the waste we have perpetrated in the name of good taste or good design.

In terms of our whole approach to architecture, we should not start out by thinking how we can tweak the aesthetic experiences of modernism to make them less ecologically harmful, but by considering from scratch what sustainable living will look like.

IF WE LOOK AT THIS HOUSE, WE SEE IT ALREADY AS A CERTAIN WAY OF DOING THAT WE CAN REPLICATE AND THAT WILL CREATE A CERTAIN REALITY. BUT, IF IT STAYS AS A CATHEDRAL, IT’S JUST A SINGULAR EVENT. IF VILLA SAVOYE IS JUST A SINGULAR EVENT IT DOESN’T RUIN OUR PATH TOWARDS SUSTAINABILITY.

But the Vila Savoye was not a single building, it was and still is part of a movement, and therefore its implications lie beyond its walls. The reason I sound so critical of a building that I admire in its own terms is because it is still influential. It’s so deep in our DNA, and many or most in the world of architecture and construction are, up to now, worryingly superficial in the way that they seem to feel we need to change things.

The idea of purity, of pure space is so historically situated. You know the whole idea of that discussion of abstract spatial design arises only when central heating comes in. Until then, it’s too stupid to even consider. When I started out in modernist architectural history I didn’t consider the enormous energy inputs required by the buildings I admired. Since I started taking my research in these directions, I’ve been really struck by the way we inherit assumptions and perceived values and carry them on without even thinking.

What we accept as intellectual and cultural progress can, when considered through an ecological lens, be incredibly wrong and damaging, and I think this is something we must be increasingly attentive to, to search for this more complete picture of what design needs to be today.

AS WE LEAVE THE TIME OF EASY HEAT AND STRIVE TO REBALANCE OUR MODERNISTIC TENDENCIES IN RELATION TO NATURE AND A RESPONSIBLE RATE OF ENTROPY, WE NEED NEW OPTIMISTIC IMAGES OF FUTURE EXISTENCE. WHAT DO YOU THINK THEY ARE?

The answer is very simple. It’s renewable electricity.

But we can’t, for the foreseeable future, generate enough of it to just substitute our fossil fuel use. For instance, we cannot just replace oil with electricity and batteries overnight. It would be, and is turning out to be, an ecological catastrophe. For now there is always a limit. Perhaps technologies might develop to the point where that’s no longer the case. But while that’s still the case, we should make use of energy as strategically and efficiently as possible.

Similarly, things like energy-intensive industrial processes need to be synchronized with earth’s cycles, not simply those of financial markets. I can’t see us getting fully away from steel because there’s nothing else that does what steel does anything like as well as steel. But we’ll need to use much less of it, and produce it with renewables, on sunny days and on windy days, and not when it’s raining, still, or at night. As it is, we have this mentality and this entire kind of financial set of assumptions: the plant is expensive, and energy is cheap. So you build your plant and then you just pay whatever the price is for the energy, and you keep the plant running the whole time. That is the fossil fuel way that is threatening the viability of life on earth.

I think there is a need for optimism, but I think the optimistic buildings of the present look very, very different from the optimistic buildings of the 1920s and 1930s.

So, the Villa Savoye is optimistic about the infinite capacity of humanity to fix things through high energy technologies. It is optimistic about the human capacity of controlling nature.

The optimistic building of now is small, low energy, ideally retrofitted rather than newly built. It is as passive as it can be. It’s perhaps going to require quite a lot more planned maintenance because it will use materials that aren’t as intensely heat processed and therefore are often less durable.

It may even look, in some ways, like a step backwards or a step down, but it’s a step towards a world in which we recognise that we can lose some material affluence in favor of achieving a reconciliation with natural cycles. I think optimism is, therefore, a kind of joyful embracing of the need to step downwards: a humbleness towards our ecosystem.

It’s fascinating and exciting, and I think it’s a huge opportunity for architecture. We need good, interesting, sincere architects to redesign everything more fundamentally than even Le Corbusier envisioned. We will have to rediscover the lost regional sophistication about local, low-energy materials and passive comfort, that was completely, deliberately undone by modernism. Somehow, we have journeyed in a full circle from essential low energy, vernacular buildings, through to high energy global uniformity of sensation, of unlimited fossil fuel use, and we are now on our way back to a socially and geographically conscious re-embraceof place, and of varied, life-enhancing, low—energy architectures.

11.01.2023

巴纳巴斯-考尔德:从根本上说,现代主义建筑诞生于对化石燃料的狂热消耗。因此,它教给我们的大部分经验在气候危机时期几乎是完全错误的。现代主义对材料、服务和运输的态度大多导向了生态灾难。

我深感忧虑的是,我所从事的专业——建筑学教育——继续将现代主义奉为正面的、直接的教条,供学生和从业人员学习当今建筑的外观、材料和性能。

萨伏伊别墅是永恒的吗?

我希望三十年后,甚至十年后,如果你再问这个问题,一定会引起哄堂大笑。我不认为它是永恒的。之所以会有这样的感觉,也许是因为我们还处在那个时刻;并不是说它本质上有什么永恒性,只是我们还没有向前看。我们之所以认为它具有当代感,是因为我们仍在复制它,也是因为我们仍存在于一个世界——在技术和理论上都源于那个热衷于挥霍化石燃料的时代。我们仍然依赖化石燃料能源。在建筑业的各个领域,我们仍在尽可能地用热能代替劳动力。

萨伏伊别墅是否象征着我们仍然向往的现代生活方式?

我想说,萨伏伊别墅是一台燃烧化石燃料的机器,既可以在现场燃烧,也可以远程燃烧,尤其是远程燃烧,这在 20 世纪 20 年代还是一件新鲜事。早期现代主义的兴奋点之一是消除现场木材或煤炭燃烧的混乱和维护工作——肮脏且需要枯燥地搬运燃料。现代主义者试图用燃油锅炉、电加热和电照明设备取而代之,这些设备更加清洁,而且似乎具有神奇的魔力,你只需轻按开关就能实现一切,而不是让仆人提着一桶煤进来。

在勒-柯布西耶探索新能源技术对生活和建筑的意义的过程中,我将萨伏伊别墅看作是他的晚期作品。”房子是生活的机器 “这句话已被广泛讨论,但它的含义是明确的:正如其他机器将化石燃料能源转化为工业产品一样,房子作为生活的机器,将化石燃料能源转化为生活方式。

“现代的”生活方式正是从大规模生产中诞生的。 萨伏伊别墅依靠并庆祝了在其建造前几年发生的两场革命:内燃机和远程集中供电。这两项革命使别墅得以立足于巴黎郊外 20 公里处。

私家车使富人能够在周末飞速离开巴黎。正如大家所知,别墅建筑的底层平面是依据汽车的转弯半径设计的。在早期的草案中,勒-柯布西耶甚至提议将汽车开上一条斜坡,穿过整栋房子,停在大楼的更高处。

这也是一座关于电的建筑。最初,勒-柯布西耶非常热衷于尝试用电加热,但所需的能源水平需要专门为这座房子建造一个变电站,即使是对于富裕的客户来说,这也远远超出了预算。

当然,这些材料也是化石燃料革命的材料--高热力强度。勒-柯布西耶在他的著作中明确提到不使用天然材料的愿望。他所倡导的 “工业材料 “是使用大量化石燃料高热量加工而成的材料。因此,粘合混凝土的水泥和加固混凝土的钢筋,在几千年的人类历史中都是众所周知的。只是从十九世纪末开始,由于廉价的化石燃料热量的日益丰富,它们才被大量使用。

其后果直接体现在设计上。

没错!巨大的窗户和荒谬的表面积与体积的比率都是对化石燃料热量的赞美。如果你看看任何工业化前、化石燃料使用前的窗户,窗格都非常小,而且通常很不平整。到了现在,你可以看到巨大的玻璃片,其大小可以让你的视线从沙龙出离到中央阳台后再上升阳光露台。

这些玻璃片非常大,而且装在移门里。在这个时期,只有通过煤炭和越来越多的石油才能获得廉价的热量,玻璃技术才能达到这样的水平。因此,建筑材料的生产需要大量热能,而这些材料造就了现代建筑的五要素:底层架空、自由平面、自由立面、横向长窗、屋顶花园。

自由平面的实现要归功于混凝土和钢材,这意味着垂直墙壁不再起任何作用。自由立面以略微不同的方式表达了同样的意思。底层架空再次以略微不同的方式表达了同样的意思。所有这些自由的结果是,几乎每一面墙壁、天花板和地板都是建筑物的外表面。从一个房间漏出的热量几乎不会进入另一个房间。

然而,所有的围护结构都是没有隔热层(或隔热层非常非常薄)的单层混凝土和钢材。因此,这座建筑就是一座连续的、巨大的冷桥。

这对于早期现代主义建筑来说是至关重要的,而不是附带的的。无论是在寒冷还是炎热的气候条件下,廉价的能源都使它们摆脱了一贯的方式。在过去的 100 年中,许多设计态度都是以巨大的化石燃料投入为代价,来反叛前几代人明智和基本的做法。

从历史上看,在冬季寒冷的地方,人们总是将房间集中在热源周围,以尽可能地保存每一焦热量,并在房间之间共享热量。建筑师将表面积与体积的比例降到最低。而在早期的现代主义别墅中,这种情况恰恰相反。设计师们对能够拥有巨大的表面积和极小的室内外障碍物感到无比兴奋。他们在概念上和视觉上都考虑到了这种障碍的打破,但在实践中,他们只能通过廉价的供暖来实现这一点。这些宽敞、开放式的房间,有时会将一层以上的连续空间连成一体,这些房间就会变得过于通风而无法居住、要不是有着强大的中央供暖系统,也将令人不适。

它是权力和统治的象征吗?

是的,我认为早期现代主义有一种非常强烈的人定胜天的精神。萨伏伊别墅就属于这一类。

但归根结底,它也是一个明显的傲慢的案例,就像我们现在的处境一样:我们是自然的一部分,而不是自然的统治者。在萨伏伊别墅的微观尺度上,勒-柯布西耶征服自然的欲望超越了激发他灵感的技术的能力。结果,这并不是一台适合居住的机器。

最终,设计所要求的热量输入水平甚至超出了一个富裕家庭的承受能力,这个家庭的一个儿子因建筑潮湿而健康受损。

读了您的书(《建筑,从史前到气候危机》,鹈鹕出版社 2022 年版)之后,我的印象是,您在寻找一种决定论,即生活的形式是由历史中能源生产相关技术的发展决定的。除了能源之外,我们也想问您,您是否发现,比方说,有其他因素将这座房子与其他被认为是浪费能源的房子区分开来。

你说我似乎在寻找决定论。除了回答一个简单的问题之外,我并没有在那本书中寻找任何东西: “如果倒推,关于能源使用与建筑造型,我们目前的关切是什么?” 后来发展成 “能源使用和建筑之间是什么关系?” 而答案--建筑与能源始终密不可分地联系在一起--一次又一次地以压倒性的优势出现。答案多种多样,包括因纽特人住房的季节性、古迹的能源基础、乔治亚风格房屋的窗户、勒-柯布西耶的别墅,一直到气候危机。

萨伏伊别墅之所以能成为一个很好的案例研究,是因为勒-柯布西耶异乎寻常地善于根据当时还处于相对早期阶段的技术变革,迅速重构他的建筑作品。这就意味着,没有那么多的混乱来自于不得不去解释那些传统主义者的借鉴——来自于过去的诞生于延续几代人的能源变革过程中的建筑,举例来说,就像同一时期埃德温-勒琴斯(Edwin Lutyens)那样。

这仍然是一座围绕汽车、集中供暖、材料便捷运输、混凝土和沥青以及其他各种非常相似的技术而设计的建筑,就像勒-柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)一样,。但是,他们也沉溺于与数百或数千年前的建筑进行着非常复杂的美学讨论,这仅仅使得故事的脚注多得可怕。

而对于勒-柯布西耶,由于他是如此无情和犀利地与时俱进,因此分析简洁明了。

从更具艺术性的角度来看,当你身临其境时,作为一名建筑师,或者作为一个有意识地关注建筑的人,它具有什么样的客观品质,是物质的还是理论的?它的整体效果是否能克服我们的道德疑虑?

对我来说,最伟大的现代主义者给我带来的巨大积极影响是,他们的意愿去真正地深入地重新思考问题,并从令人惊讶的地方汲取影响。他们有能力掌握足够多的技术数据,这意味着他们在设计时掌握了正确的信息,而不是照抄他人的样式且假设技术要求也是足够相像可以起效的。

就参观萨伏伊别墅的审美和知识体验而言,我希望人们能从中学到如何围绕当下的条件重新全面思考建筑。 作为一个项目,它在这方面做得非常出色。 因此,我们现在可以从它身上学到的是其反思的深刻性,而不是它的材料或样式。

我们面临的挑战甚至比早期现代主义者面临的挑战更大、更令人兴奋:他们的挑战是在化石燃料主义内部的转变,而我们则需要在化石燃料主义之后寻找新的建筑。

这是一个更大的转变,例如,开始采用一种建筑文化,以适应可再生能源发电量随天气起伏而波动的电力供应。可再生能源本质上是间歇性的。重新设计我们的生活和建筑,使之成为可再生能源系统的一部分,是一个需要柯布西耶团队来解决的挑战。

我第一次参观萨伏伊别墅时,就觉得它非常漂亮,而且非常迷人,不过,在经历了一个多世纪的汽车驱动的城市发展之后,我失望地发现它被包围住,被郊区化了,其开阔的乡村美景早已不复存在。现在,我发现我对它的喜爱被抑制,因为得知了它所代表的意义,使当时最新的化石燃料奢侈品变得如此诱惑和迷人。

有一种特质,几乎是直接到达你这里,洗手,在两个交通流线中选择一个在里面走动,然后坐在屋顶的大露台上,这样的感觉有一种特质。它提供了某种自由。在追求快乐的过程中,我们能否给自己一些自由?

双循环是一种挥霍,我们必须停止挥霍。在单户住宅中,单循环就足够了。绝对没有理由再建一个循环通道,因为建造和供暖都要耗费能源和碳排放。这会降低密度,从而增加对交通的需求。萨伏伊别墅的设计方式非常宽敞,产生了全新的空间类型,这只是因为坐在屋顶上晒太阳,或者从建筑中的另一小块开放空间获得一个不一样的观景点。当建筑周围也有空地时,它们固然光彩夺目,但却是以额外的碳排放为代价换来的奢侈品。

在气候危机下,我们需要思考的不是这些奢侈品。我们需要寻求的是一个温暖的小窝--冬天家中真正舒适的地方--这是一种令人惊叹的感官奢侈。

在英国,冬天通常又冷又潮湿。今天晚上也不例外,我坐在只有天然气中央暖气的房子里,天然气中央暖气既费碳又昂贵,所以我们一直都关着暖气或把温度调得很低。因此,我穿着保暖连身衣,围着围巾,如果我们有一个小小的温水池,我无法形容我是多么喜欢它,我可以接近它,选择我的距离,就像集中供暖之前的情况一样。

热愉悦(《建筑中的热愉悦》,丽莎-赫松,麻省理工学院,1979 年)与现代主义者在我们身上涂抹的热米色相去甚远。你问到了进入建筑的体验: 我完全同意对建筑学意义上的长廊的思考,但真正可持续发展的独户房屋的建筑长廊可能很短,因为它可能很小。化石燃料和住房的主要特点之一就是降低了大型建筑的建造成本。因此,当你查看农业时代的任何非精英住宅时,它都比现在世界人口中,类似的财富百分位人群的住宅要小得多。

因此,如果低碳住宅的面积较小,那么穿过住宅的长廊就会较少。 但这并不意味着设计师不能以精妙而有趣的方式考虑从室外到室内的体验,尤其是在热能和光线方面。好的被动式热能设计可以带来非常丰富的建筑和美学体验,在寒冷的天气里可以收集所有的太阳辐射,在温暖的天气里则可以将其阻挡在外。

中层低碳密度也给建筑设计师带来了令人激动的挑战:如何通过优雅周到的规划来实现密度,以及密度如何促进建筑物之间、居住单元之间的相互温暖。这是建筑思想和审美体验极为丰富的领域。但这种审美体验并没有在视觉上非常壮观,即刻上镜——这一特质在 20世纪和21世纪初被赋予过高的特权。它更倾向于热体验,而热体验在杂志和网站上是很难传达的,因此总是会受到建筑出版业的歧视。但是,对于居住在能耗低、温度调节性好的房屋中的体验来说,热愉悦感要重要得多。越来越多的研究表明,热能比视觉更有利于健康、快乐和幸福。

温暖舒适是一种巨大的享受。每个季节都会带来不同的乐趣。因此,下一个冬天,当第一个真正寒冷的日子来临时,你会有舒适惬意的愉悦体验;或者下一个夏天,当室外烈日炎炎时,你走进一间凉爽宜人的房子--这些愉悦永远不会过时,因为即使是最好的景观,也会随着时间和习惯而失去一些最初的力量。热愉悦绝对是古往今来建筑的核心要务,对于除了最富有的 5%左右的人之外的其他人来说,热愉悦始终比建筑外观更受关注。即使对权贵来说,热舒适也是至关重要的。路易十四的卧室位于凡尔赛宫的中心,装饰得非常华丽,但从面积上看,却比宫中其他主要房间小得多--事实上,小到用壁炉取暖也很舒适。

您认为柯布西耶会如何看待 “减量化、再利用、再循环”?

在勒-柯布西耶设计白色别墅期间,他将自己与古色古香的建筑乐趣相提并论。勒-柯布西耶设计的萨伏伊别墅的一切都焕然一新。大约在 1935 年之前,他的作品中任何看起来有点磨损的东西都是失败的,都需要更换。许多建筑师仍然执着于这种理想——保持崭新。

其他方式也确实存在--日本的景观传统赞美苔藓的缓慢生长,或水从墙上流下并留下痕迹。它赞美事物被替换,但并非毫无区别,这样你就能通过时间的推移感受到一种源于长期使用的优雅,而我认为我们在很多当代建筑中都很难做到这一点。建筑在完工后会尽快被拍成完美的物件。

对新的和闪亮的崇拜在生态上是灾难性的。在气候危机的情况下,让人们看到你的房子或公寓里有大量崭新的、焕然一新的工程,这在社会上应该是令人尴尬的。我们应该感到有必要为开膛破肚、更换浴室和厨房而道歉,因为这是令人尴尬的必要之举,而不是自豪地炫耀我们以好品味或好设计的名义造成的浪费。